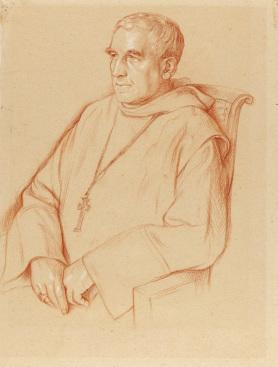

Some notes on the 50th anniversary of the death of Abbot Wilfrid UpsonOn this day fifty years ago occurred the death of Abbot Wilfrid Upson OSB (1880-1963), the first abbot of Prinknash Abbey near Gloucester, and author of Movies and Monasteries in USA (Gloucester: Prinknash Abbey, 1950), about which I wish to write in today’s blog. As some of you may know, I have been researching the religious applications of film and photography for many years. and am particularly curious about the way these arts were used, interpreted and criticised by clergymen in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Abbot Wilfrid is a little bit unusual in that – as well as making 16mm home movies -he travelled to Hollywood and took an inquisitive interest in the workings of the film industry.

John Henry Neil Upson was born in London on 28 June 1880. His family belonged to a Nonconformist sect, The Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion, and kept a strict Sunday observance that saw books and toys packed away from Saturday night to Sunday morning. In his late teens he became interested in the Church of England, attending High Anglican services at St Augustine’s, Stepney, where the name of the Pope was included in the prayers. He got involved in youth work, running clubs for boys at the St Frideswide Mission in Poplar as well as travelling to Kent to help with evangelical missions for the hop-pickers in the fields. A large marquee was set up in which they held concerts during the week and, on Sundays, religious services at which he played the harmonium and helped lead prayers. Adopting a classic pre-cinema technique, a large lantern sheet was erected in the middle of a field on which to project devotional images such as the Stations of the Cross.

While Upson was engaged in these activities, a young Anglican medical student named Benjamin Fearnley Carlyle (1874-1955) was struggling to establish a tiny monastic community at a house in the east end of London. ‘Br Aelred’ as Carlyle called himself, was by no means the first Anglican drawn to religious life: the tradition stretches as far back as Nicholas Ferrar’s community at Little Gidding. The 19th century saw a surge of interest in monastic life, spurred on by the Gothic revival in art and architecture, the influence of Romantic literature, and the religious ideals of the Oxford Movement. From around 1845 Anglican Sisterhoods began to rise up under the direction of men such as J.M. Neale and Pusey. The development of religious life for men was later and slower. ‘Father Ignatius of Jesus’ (Ignatius Lyne, 1837-1908) made the first serious attempt in the early 1860s, followed by the Society of St John the Evangelist (‘Cowley Fathers’) in 1865, the Community of the Resurrection (1892), the Society of the Sacred Mission (1893) and the Society of Divine Compassion (1894.)

By 1896 Aelred Carlyle had gathered around him a few sympathetic young Anglo-Catholics at ‘The Priory’ in London’s Isle of Dogs, where an idiosyncratic form of monastic life was combined with pastoral work among the working boys. They had to leave this house in 1898 and over the next few years the community flitted from place to place, gathering and losing members, changing its habit from black to white to Cistercian black and white. In 1906 they returned to Caldey Island, where they had spent a short interlude in 1901-2. This was to remain their home for the next 22 years.

Having joined the Church of England, John Upson gradually felt he had a vocation to the religious life and contacted the Superior of the Society of the Sacred Mission at Kelham Hall in Nottinghamshire. After he failed the Society’s medical, he recalled seeing a magazine called PAX which was being printed at Kelham. This was the magazine of the monks of Caldey, and so he contacted Aelred Carlyle to enquire about joining their community instead. They met for an interview in London, after which Upson arrived on Caldey Island in April 1908.

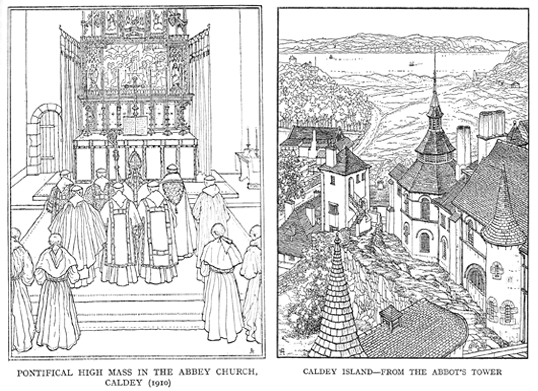

Carlyle’s vision was influenced by the romantic medievalism of his time, and the community became closely associated with the contemporary Arts and Crafts movement. Work carried out by the monks included painting, woodcarving, sculpture, stained glass manufacture, pottery, calligraphy and metalwork. Br. Wilfrid felt at home on Caldey, and was able to develop his artistic skills with pen and ink sketches and small watercolours. He excelled at other visual media too, organising theatrical productions of medieval Passion Plays during Lent that were performed by the monks as well as local islanders. This took place for many years and became well-known. Writing in Time and Tide magazine, Miss Christopher St. John enthused: ‘Not since Gordon Craig’s Masque of Love have I seen such harmonious grouping and movement . . . the great achievement of the Caldey Passion is that visions are created instead of illusions.’ He was in fact adept at illusions too, as he had learned a number of conjuring tricks and enjoyed entertaining the community with magic shows.

The monastic life led on Caldey Island went far beyond what was generally accepted within the Church of England, combining spartan austerity with observance of the Rule of Saint Benedict, full Roman liturgy involving incense and Gregorian chant in Latin. Tension grew between the community and the Anglican authorities, which eventually led to a parting of the ways: in 1913 almost the entire community converted to Catholicism. Although in some respects this made life much easier, the community was severed from its Anglican friends and benefactors, many of whom felt grieved at the loss of the money they had invested in the unfinished building projects. It soon became apparent that the financial situation was dire.

Aelred Carlyle was ordained priest and returned to Caldey to be blessed as the Benedictine Abbot of Caldey in October 1914. He struggled on for seven years before resigning and moving to Canada where he spent the next thirty years doing missionary work in Vancouver. While the local bishop assumed jurisdiction over the monastery, Wilfrid Upson – who had been ordained priest in 1915 – was appointed Prior. To sort out the financial mess, Pius XI asked the Abbot General of the Cistercians if he could purchase Caldey, as the Benedictines had been offered a home at Prinknash Park near Gloucester. They moved off the island in 1928, floating the wooden refectory tables over the water to the mainland and transferring all their goods to the Tudor mansion of St Peter’s Grange at Prinknash, the former home of the pre-Reformation Abbot of Gloucester Abbey. In 1929 the community joined the Cassinese Congregation of the Primitive Observance. This was, and remains, the largest of the Benedictine congregations with houses all over the world. The peculiar background of Caldey had made the community reluctant to abandon their own ideals and practices, and they were resistant of being absorbed into a highly centralised order. Exhausted by the strain, Fr. Wilfrid resigned as superior and went to act as chaplain to a community of nuns in Westgate-on-Sea.

Monastic life continued to flourish at Prinknash and when the monastery was raised to the status of an abbey in 1937, Wilfrid Upson was elected its first Abbot. The community grew to such a size by the early 1940s that it was necessary to open overflow houses at Bigsweir and Millichope. Plans were also put in motion to start new foundations at Farnborough and Pluscarden, in addition to building a new monastery at Prinknash. Much of the building work was carried out by the monks themselves and Abbot Wilfrid recorded some of these activities in his home movies, which he shot on a 16 mm camera. He took still photographs too, and continued to enjoy sketching and painting. The community were regularly entertained with his film-shows, recording visits to places of interest – such as Lourdes – as well as scenes of monastic life. Arranging the new foundations required him to travel outside the monastery, making site visits, negotiating with lawyers, contractors and benefactors, as well as trying to raise funds from Catholic parishes, guilds and societies. This was particularly challenging in postwar Britain, given the scale of the abbot’s projects, and it seemed sensible to cast his net slightly wider. And so it was that Abbot Wilfrid, accompanied by his subprior Fr. Norbert Cowin, sailed to New York in November 1947 on a fund-raising trip that would last six months, cover some 20,000 miles, and involve two separate visits to Hollywood.

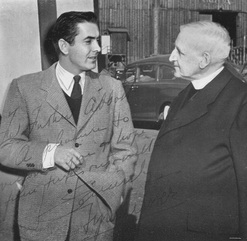

The abbot with matinee idol Tyrone Power (left), swashbuckling hero of The Mark of Zorro (1940), Prince of Foxes (1949) and The Black Rose (1950).

‘All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up…’

‘All right, Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up…’

Here, Cecil B. DeMille – director of sits between Abbot Wilfrid (left) and Fr. Norbert (right). DeMille began directing in 1914 and was the first Hollywood director to become a celebrity in his own right. His films include several Biblical epics such as The Ten Commandments (a silent version in 1923 and a very different Technicolour film starring Charlton Heston in 1956), The King of Kings (1927), The Sign of the Cross (1932) and Samson and Delilah (1949.) They also met with Sam Goldwyn and the Warner Brothers, Harry and Jack.

Abbot Wilfrid’s visit was a mixture of religious discussion and film shows, as well as (it must be said) a great deal of socialising, even if this was undertaken for a good cause. Before leaving Hollywood he managed to assemble a seventy-strong audience for a screening of his own colour Kodachrome 16mm film, Abbey Builders of the 20th Century, which was accompanied by a talk on the community’s history.

Abbey Builders had been filmed in 1940, and incorporated footage of some of the great English ruined abbeys – such as Rievaulx and Fountains – which were then juxtaposed with shots of the overcrowding at Prinknash. The abbot was shown discussing with the other monks the need to build a larger monastery, followed by close-ups of some of the monks looking doubtful or asking one another sceptical questions. Other scenes include the laying of the foundation stone, vignettes of daily monastic life that emphasised the manual skills required for the building work, and a lovely sequence where a rainbow breaks over Prinknash – no doubt Abbot Wilfrid really was hoping for a pot of gold at the other end.

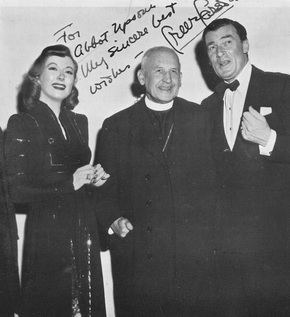

Amongst the audience were Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon (right.)

Cinema goers were used to seeing them together, both on the screen and off it, as they were good friends in real life and played a married couple in no fewer than eight films: Blossoms in the Dust (1941), Mrs Miniver (1942), Madame Curie (1943), Mrs Parkington (1944), Julia Misbehaves (1948), That Forsyte Woman (1949), The Miniver Story (1950) and finally Scandal at Scourie (1953.) They were just the sort of screen couple of which the League of Decency could approve – wholesome, virtuous, morally upright, mutually supportive, kind and courageous. Little surprise that the abbot was smiling.

Others who watched the abbot’s film included movie columnist Louella Parsons, Loretta Young (fresh from playing opposite David Niven and Cary Grant in The Bishop’s Wife), Ruth Hussey – who played the photographer in The Philadelphia Story (1941) – and Pat O’Brien, a former altar boy who was cast as a priest in several films, including Angels with Dirty Faces (1938) and Fighting Father Dunne (1948.) Most of these stars were Roman Catholics, either from birth or -like writer Clare Booth Luce, who invited Abbot Wilfrid to her house – adult converts. Luce had been received into the Catholic Church in 1946, two years after losing her young daughter in a car accident, taking to Catholicism with the same zeal she applied to all her work. In 1949 her screenplay Come to the Stable was made into a film, starring Loretta Young and Celeste Holm as two French nuns founding a children’s hospital in the New England town of Bethlehem. Abbot Wilfrid met Loretta Young again before leaving Hollywood when Louella Parsons organised a tea party for the two monks, inviting the actress and her husband producer Tom Lewis, along with Maureen O’ Sullivan, Irene Dunne and Mgr Patrick Concannon of Good Shepherd parish, Beverly Hills. The group may all have appeared highly pious, but their personal lives were often more tangled than those of the characters in their films, and some of Loretta Young’s early films might have brought a blush to the abbot’s cheeks.

The only disappointment at Louella’s tea party was that she had a 35mm projector and the abbot was therefore unable to show the guests any of his 16 mm films. In addition to Abbey Builders he had taken his colour film of a day in the life at Prinknash Abbey, which was titled (after a local saying) As Sure as God’s in Gloucestershire.

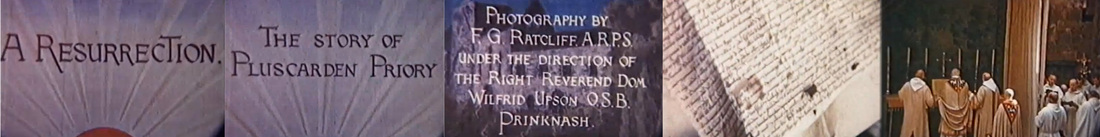

The two monks took their leave of Hollywood in March 1948 and spent the next few weeks journeying east, visiting monasteries in Kansas, St Louis, Chicago, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington before reaching New York from whence they returned to England. In terms of raising funds the expedition fell short of expectations, but this did not prevent the foundation at Pluscarden going ahead. A special Mass was celebrated at the ruined monastery in Moray on 8 September 1948 to celebrate the return of monastic life to the spot, after almost 400 years. Abbot Wilfrid was there with his camera: