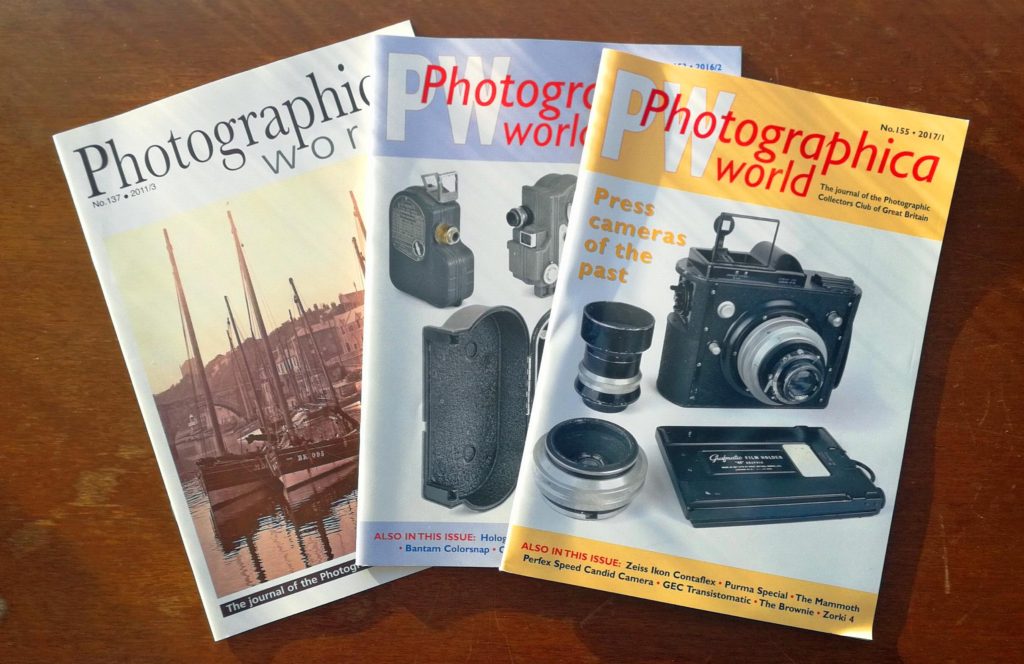

This carte-de-visite was taken in the late 1880s and shows the Countess of Clancarty (1867-1906) – a singer, actress and music-hall entertainer better known under her stage-name of Belle Bilton. It shows her in costume and was taken in the Ebury Street studios of fashionable London photographers W. & D. Downey, opened in 1872 by William Downey (1829-1915) while his brother Daniel managed their studio in Newcastle. The Downeys took many portraits of Queen Victoria and the royal family, as well as aristocrats, society beauties and famous actresses. Belle was photographed by Downey several times, and also sat for other society photographers such as Alexander Bassano.

Background and Stage Career

Isabel Maud Penrice Bilton was born in 1867, the daughter of Sergeant John George Bilton of the Royal Engineers. Under the stage name of Belle Bilton she made her name as a music hall entertainer at the Alhambra and the Empire and other venues. Sometimes she appeared with her sister – an advert for a performance at the London Pavilion in Piccadilly in 1886 shows the ‘Sisters Bilton’ on the billing.

Lord Dunlo

Richard Somerset Le Poer Trench, 4th Earl of Clancarty, using a stereoscopic camera around 1864, three years before the birth of his son.

At the Corinthian Club towards the end of April or beginning of May 1889, Belle met a young aristocrat – William, Viscount Dunlo, son of Richard Somerset Le Poer Trench, 4th Earl of Clancarty and heir to the title. Like Belle, Lord Dunlo was twenty years old, and the couple quickly fell for one another: they were married soon after, at Hampstead Registry Office, on 10 July 1889. The groom’s father was not impressed at his son’s choice of bride, and William had already incurred the Earl’s displeasure due to his lack of enthusiasm for the army career that had been planned for him. As it had already been decided that William would benefit from foreign travel in the company of a sober and morally-minded mentor, his scandalous marriage to a music hall entertainer proved the last straw: the Earl forced his newly-wedded son to sail for Australia immediately under threat of losing his inheritance. A divorce case – which in those days depended upon proving adultery – was at once initiated, with the Earl determined to use every means in his power to blacken Belle’s name and have the union dissolved with his family’s honour intact.

The Trial

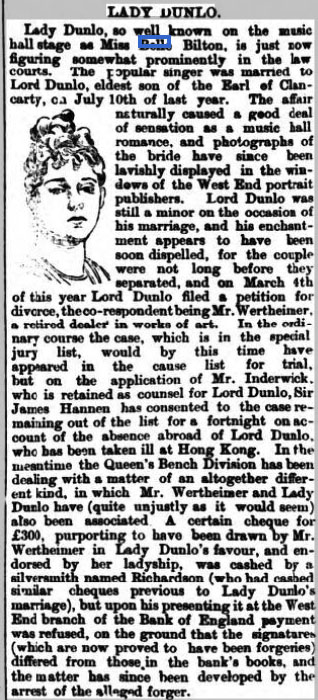

Over the next few months evidence was gathered, while Belle – in the absence of her husband – continued to socialise and pursue her stage career. In April 1890 she played the title role in the ‘burlesque extravaganza’ Venus at the Plymouth’s Theatre Royal. The trial opened in July 1890 with Sir James Hannen sitting as judge, Sir Charles Russell prosecuting, and the solicitor general Frank Lockwood QC representing Belle. The adultery trial had been preceded by a separate court case in which Belle was implicated in forgery; although the matter was quite independent of her marriage to Lord Dunlo, it was clearly intended to blacken her character – an objective that was largely thwarted by her being found innocent.

Eastern Evening News (Saturday 12 July 1890) p.2

It became apparent during the adultery trial that Belle was more sinned against than sinning, and the Earl and his associates came out looking worse, having instigated various machinations to make Belle look bad. As recent events have made all too clear, rich and powerful men can be responsible for all sorts of abuse to protect their interests. When Lord Dunlo declared he believed his wife to be innocent of the charges, the case collapsed, and he returned to live with Belle. Cut off from his father’s allowance, the couple were required to live off Belle’s earnings from the theatre – estimated at around £1,500 a year. Some felt that the publicity of the court case might actually help matters:

‘I dare say the photographs of Lady Dunlo (Miss Belle Bilton) are more marketable now than ever. I don’t know if this fascinating young lady has been paid liberal terms by Bassano and the other photographers to whom she has given sittings, but she certainly deserves to remunerated handsomely. She will sell like ripe cherries from now until her divorce trial comes off.’

– London and Provincial Entr’acte (Saturday 12 July 1890) p.5.

The couple did not have long to wait. Belle’s father-in-law died less than a year after the trial, aged only 57. In May 1891 her husband became the 5th Earl of Clancarty, and Belle assumed the title of Countess of Clancarty. The couple had five children, including the 6th and 7th Earls of Clancarty.

Belle with her twin sons Richard and Henry, born Devember 1891. Photographed by Bassano ca. 1893-4. Reproduced courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

Sadly, Belle died of cancer on 31 December 1906 at Garbaldy Park, Ballinasloe, County Galway, Ireland, at the age of only 39. Carte-de-visite portraits of her – both in theatrical costume and as herself – are fairly easy to find and so it is tempting to consider building up a collection of these. Belle’s short life is intriguing for anyone with an interest in late Victorian theatre, and there is something inspiring – and remarkably topical – about the story of how this young woman refused to be crushed by powerful men who sought to silence her.