This was the view from my bedroom window a couple of days ago, and when driving up through the Exe Valley last week I noticed thick banks of white mist hanging over the fields to the side of the road and thought of Keats’ lines in Ode to Autumn:

Seasons of mist and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun.

Autumn is almost upon us now, and I like the pleasing contrast between the white mist and the piles of bronze and gold leaves that are starting to accumulate on the ground. I call it ‘mist’ rather than ‘fog’ because I’ve always associated the latter with the sea. Strictly speaking, however, the distinction lies in visibility: fog is thicker than mist, and there is a precise point at which one becomes the other. Hill-walkers, drivers, seafarers, pilots and others have good reason to dislike such treacherous conditions: routes are hidden from view, dangers concealed, sounds are muffled and distances become hard to judge. Fear of what lies within the mist, or fog, is also a familiar trope from the worlds of film and literature. Perhaps the most notorious example would be London’s ‘pea-souper’ fogs, which have provided the atmosphere (literally) for numerous acts of murder and skulduggery by Victorian villains.

Contrary to popular belief, Conan Doyle never used the term ‘pea-souper’ in his Sherlock Holmes stories. Another common misconception is that the Whitechapel murders ascribed to ‘Jack the Ripper’ took place in thick fog, when in actual fact the killings ceased during the month of October 1888 – the only time when there really was a pea-souper. These murders provided the inspiration for Hitchcock’s silent thriller The Lodger (1927), starring Ivor Novello as the suspected serial killer. Its full title is The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog. Although Novello’s appearance matches the description of the killer as ‘wearing a scarf over the lower part of his face’ (above) many Londoners at this time would have masked their faces in the same or similar ways to protect themselves from the damp unhealthy air. Is the lodger the killer? Viewers’ inability to decide is just another aspect of the fog’s power to dull our powers of perception.

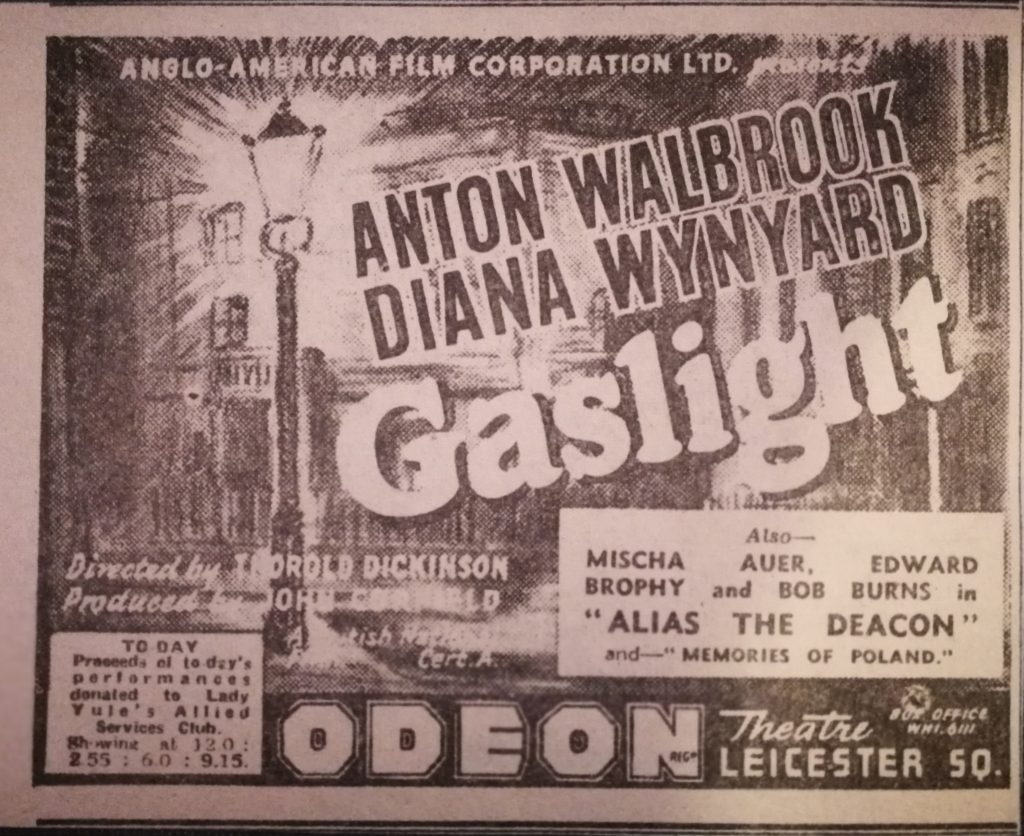

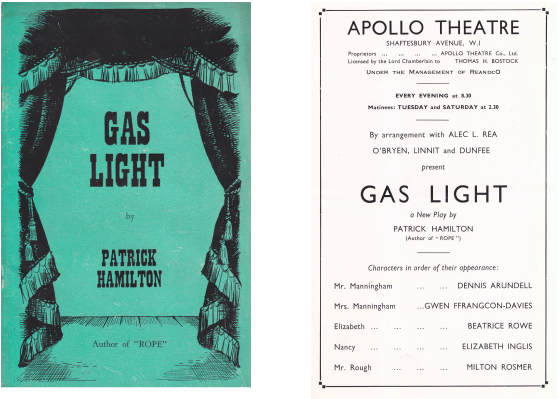

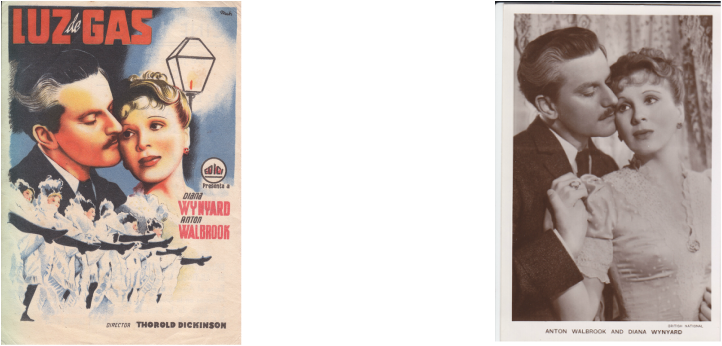

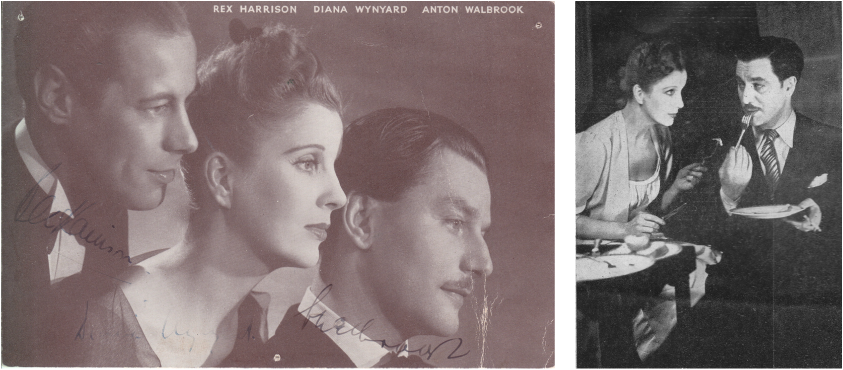

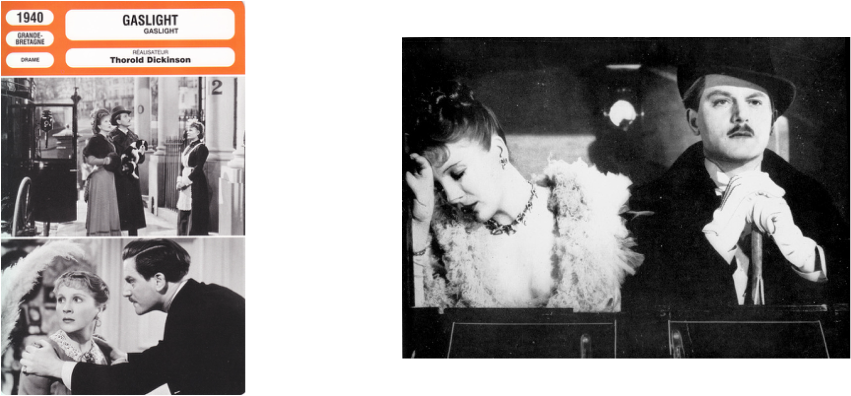

There is more confusion over mistaken identity in the film Footsteps in the Fog (1955), set in the early 1900s and based on a short story by W.W. Jacobs, the author of the classic horror tale The Monkey’s Paw. It starred the then husband and wife team of Stewart Grainger and Jean Simmons, caught up in a dark plot of murder and blackmail. The basic set-up – murderous husband teaming up with flirty maid – recalls the dysfunctional household in Patrick Hamilton’s Gaslight which was filmed in 1940 by Thorold Dickinson and then remade in Hollywood in 1944. Again, fog is used to hint at villainy – when we first see Paul Mallen (Anton Walbrook) leave the house and sets out on one of his nocturnal missions (below).

Sergeant Rough, wrapped up against the London fog with the same thoroughness as Ivor Novello – although falling short of the latter’s sartorial elegance – is able to use the fog as a cover for following Mallen as he crosses the square.

Gaslight was set around 1885, but as late as December 1952 thousands of Londoners died during a dense smog that enveloped the capital for several days. This led to the Clean Air Act (1956) which sought to banish black smoke in urban areas through the introduction of smokeless fuels. It took many years, but London’s pea-soupers eventually became a thing of the past. Times were changing in other ways, as the televised Coronation in March 1953 encouraged huge numbers of British households to invest in TV sets. The 1950s are now regarded now as the ‘golden age of science fiction’ and programmes made for television began exploring themes of space travel, frightening technology and strange creatures from other worlds. Most of these were aimed at young audiences, but a six-part series The Quatermass Experiment – broadcast in six half-hour episodes on Saturday evenings in July-August 1953 – was aimed at adults, and proved amazingly popular: when the last episode was broadcast on 22 August 1953, audience figures were estimated at around 5 million. The film industry took notice, and Hammer Films bought the rights, releasing The Quatermass Xperiment in cinemas in 1955. In America, it was renamed The Crawling Terror and was equally successful.

Although less famous, The Trollenberg Terror followed a similar trajectory to Quatermass. Occupying the same Saturday evening slot, it was broadcast in six episodes between 15 December 1956 and 19 January 1957, and then quickly bought up and remade into a film for release in 1958. In America it was renamed The Crawling Eye, possibly to capitalise on audience’s familiarity with the Quatermass film, although ‘crawling eyes’ is a perfect description of the monsters. Their appearance, however, is concealed until the end of the film by a cloud of mist; this aspect of the film, one might argue, was a direct influence upon later horror films such as The Fog (1980) and The Mist (2007.)

Most of the action takes place on the Trollenberg, a mountain in the Swiss alps which has been partially covered by a mysterious cloud that remains static over the south slopes. The phenomena is being monitored by scientists from a nearby observatory, led by Professor Crevett (actor Warren Mitchell, soon to become better known as Cockney bigot Alf Garnett), who has detected high levels of radioactivity in the cloud. This is not the only sinister happening: since the cloud’s appearance, mountain climbers have been found with their heads torn off. Crevett is joined by his old friend Alan Brooks, a United Nations expert who investigated similar goings-on in the Andes three years earlier. He arrived at Trollenberg along with two sisters, Anne and Sarah Pilgrim.

Anne Pilgrim (played by the lovely Janet Munro) is in fact telepathic, and has just finished performing a mind-reading show in London with her older sister Sarah (Jennifer Jayne.) Later, Anne’s psychic powers forge a link with the alien creatures in the mist, allowing her to visualize events on the mountainside and direct rescue operations. The aliens sense her power and try to have her killed by human ‘zombies’ whose minds they control. The presence of the sisters is one of the more intriguing elements in a film that – although full of absurdities – I have enjoyed watching several times.

John Carpenter saw The Crawling Eye as a child, and provided at least some of the inspiration behind his film The Fog (1980.) During their commentary for the 2002 special edition DVD of The Fog both he and producer Debra Hill refer to it as one of their favourite films. Carpenter’s image of the fog billowing under Dan O’Bannon’s doorway and entering his room is just one of several incidents that are reminiscent of those that took place on the Trollenberg. Another source of inspiration was a visit to Stonehenge made by Carpenter and Hill in 1977 when they witnessed a fog bank ‘just sitting on the horizon, way past Stonehenge’ causing Carpenter to wonder ‘what if there’s something in that fog?’

The malevolent beings concealed within the fog are, in this film, ghostly rather than alien: exactly one hundred years earlier, in 1880, the founders of the Antonio Bay community lit false beacons to lure a ship onto the rocks – a cruel trick allegedly employed by wreckers in Devon and Cornwall in years gone by (as depicted in Jamaica Inn for example), although there seems to be little documentary evidence to support these tales. All those aboard died in the wreck, but their vengeful spirits have returned on the night of the town’s centenary celebrations, and are intent on claiming the lives of six descendants of the original murderers.

The horrific killings take place within an eerie bank of glowing fog, that rolls in from the sea. As in The Trollenberg Terror the cloud of fog defies nature, moving against the wind. Local radio broadcaster Stevie Wayne (played by Carpenter’s then wife Adrienne Barbeau) plays a key role in the night’s events, as her radio station is located in a lighthouse overlooking the bay. From this vantage point she is able to provide a running commentary on the inexorable progress of the fog to her listeners. For me, the most memorable part of the film is listening to her voice:

‘It’s moving faster now, up Region Avenue, up to the end of Smallhouse Road…just hitting the outskirts of town…Broad Street…Clay Street… It’s moving down Tenth Street, get inside and lock your doors, close your windows…there’s something in the fog. If you’re on the south side of town, go north. Stay away from the fog…Richardsville Pike up to Beacon Hill is the only clear road. Up to the church. If you can get out of town, get to the old church. Now the junction at 101 is cut off..if you can get out of town, get to the old church. It’s the only place left to go. Get to the old church on Beacon Hill.’

Oddly enough, in James Herbert’s novel The Fog an empty church is also a place sought for sanctuary – but it is the fog that takes refuge there, rather than its victims. Apart from sharing the same name there is no relation between Carpenter’s film and Herbert’s novel, which was published in 1975. Interesting to note, nonetheless, that both men turned to the theme following their first big breakthrough. After a few minor films, Carpenter had just enjoyed his first great commercial success with Halloween (1978) and invited several of the actors to take roles in The Fog. Herbert’s first novel The Rats (1974) had sold out within weeks and attracted a great deal of attention – not all of it positive by any means – due to the graphic descriptions of death and violence. The Fog was written in the same vein and expanded upon The Rats’ theme of natural disaster brought upon by misguided government experiments; this would also form the basis of Stephen King’s novella The Mist. Herbert’s tale begins in Wiltshire when an earthquake unleashes a foul yellow fog that erupts from a crack in the earth and begins drifting through the southern counties of England. Those who are caught by it are affected mentally and the novel progresses through a series of horrific episodes in which the madness leads to murder, mass suicide, mutilation and sexual violence. The fog here does not conceal any monster other than itself; the fog is the horror, and it is slowly revealed that is has a biological life of its own.

The horror within Stephen King’s Mist shares more similarities with that of the Trollenberg cloud than either of the Fog stories. The first film Stephen King remembers seeing was The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), and he was about eleven years old when The Crawling Eye was released in the USA. The film is referred to in his 1986 novel It, which is set around the time of the film’s release in the summer of 1958. King’s youthful immersion in popular culture – early horror and science-fiction films, radio drama serials such as Dimension X and E.C. comics like Tales from the Crypt – were important influences on his later writings.

‘There’s something in the mist!’

There are a few superficial parallels between The Trollenberg Terror and the 2007 film The Mist, which was director Frank Darabont’s adaptation of King’s novella of the same name, first published in the Dark Forces collection (1980). I was on holiday in Cornwall when I first read the story in 1985, after it had been republished in another anthology, Skeleton Crew. It is by far the longest story in the collection but I read it all in one continuous session, curled up in a dormitory bed with my borrowed book and a packet of biscuits. It made quite an impression on me, and the only other story I can remember from that collection is The Raft. My vision of the scenes differed rather a lot from that of Frank Darabont, who had already brought two of King’s other stories to the screen – The Shawshank Redemption (1994) and The Green Mile (1999.) Many of King’s fans were displeased at the shocking twist – not in the book – with which Darabont decided to end the film. Personally, I approve of the ending. Few modern horror films contain genuine shocks; the final frames of The Mist have an undeniable impact that has unsettled audiences. The ending neatly confirms what has been true of all the films above – fog and mist not only conceal terrifying threats, but they cloud judgment as well as vision, rendering opaque the distinction between innocence and guilt

So when I’m walking across the fields again this week and happen to see banks of mist (or worse still, fog) drifting over the ground towards me, the question is bound to come to mind….what lies within?