As most readers of this blog will know, for over a decade I have been working on a biography of the émigré actor Adolf Wohlbrück /Anton Walbrook (1896-1967), but this weekend provided a wonderful opportunity to talk about this work as part of the Stardom and the Archive conference held at the University of Exeter, 8-9 February 2020. The conference was organised as part of the Reframing Vivien Leigh research project – I have written about the relationship between Walbrook and Leigh elsewhere on these pages – and its aims are summarised here:

Conventional critical discourse focuses overwhelmingly on the findings of archival research rather than the process with scholarship telling ‘a story about what you found, but not about how you found it.’ (Kaplan 1990: 103) The Stardom and the Archive symposium seeks to challenge this convention by centralising archival process and curatorial histories in researching stardom.

The conference has seen film scholars from all over the UK and beyond, including Australia and Turkey, come together to discuss diverse aspects of archival research, curatorial practice and fan collecting in relation to stardom. The range and quality of the papers so far has been fantastic, with an imaginative scope that includes gravesites and multi-media artefacts as well as the more traditional paper-based archives.

It was a great delight, as ever, to talk about Walbrook in the presence of such distinguished and appreciative company. My presentation was entitled Paper Trails, Masks and Mirrors: the archival quest for an elusive biographical subject and discussed the different phases of archival engagement involved in writing my biography, including the challenges of dealing with gaps in the archive, the complex relationship between Walbrook’s onscreen persona, his life as a private individual and the archival record of both his life and career. It was also an opportunity to discuss the creation of my own Walbrook collection – an archive of my research as much as a fan collection – and share some of its treasures.

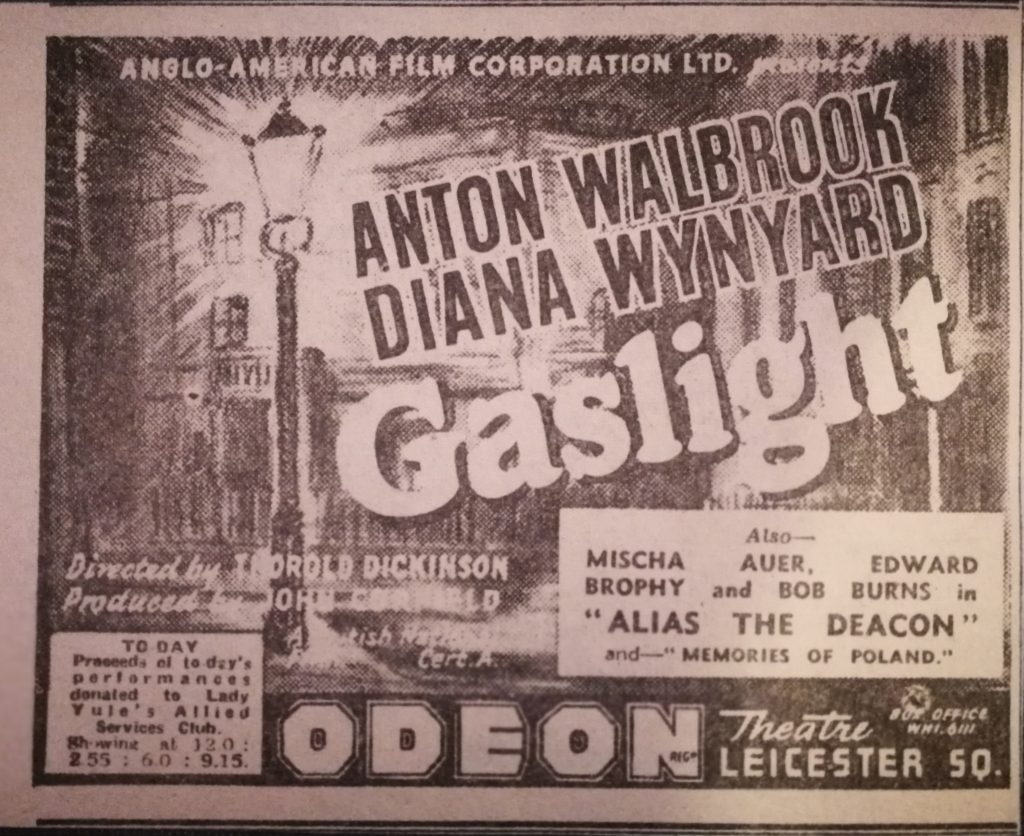

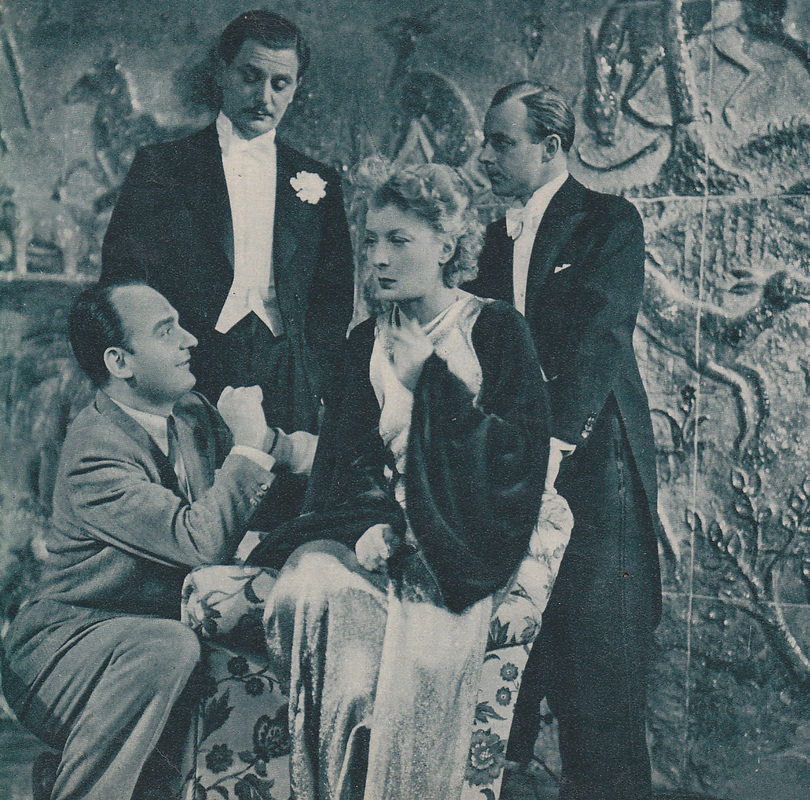

My collection includes original letters, postcards, film posters, vinyl, glass slides, lobby cards, cinema magazines, theatre programmes from the 1920s to the 1960s, copies of documentation from state archives and theatre museums, photographs, film stills, presscutting files and 16mm film reels, as well as some of the original costumes worn by Walbrook in his films, and I raised the issue of how the agenda of the collector relates to that of the biographer or researcher.

This offered a chance to revist the exhibition Anton Walbrook: Star and Enigma, which I curated at the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum back in 2013. Anyone wishing to know more about this should watch the excellent short film made by Olivia Luder and available to watch here. As another aspect of archival engagement, I also discussed the brilliant artwork by Matt Horan (Matt Mclaren), which he created by painting scenes from Walbrook’s films, cutting out the images and then reassembling them in 3-D scenarios which were then photographed and turned into prints. My paper ended with a call for more collaborations like these, in which scholars, archivists, curators, artists and fans can learn from one another through sharing their different passions and fields of expertise.

Now it’s time to return for Day Two of the conference, which will close with the launch of the new Reframing Vivien Leigh exhibition!