On the seafront at Paignton, a short distance from Oldway Mansion -photographs of which featured in my previous post on Paris Singer and Isadora Duncan – there looms the distinctive shape of the Redcliffe Hotel. Although the Singer family’s association with Oldway is well-known, Paris Singer’s ownership of Redcliffe and the surrounding area is often overlooked. Today’s post will focus attention on this.

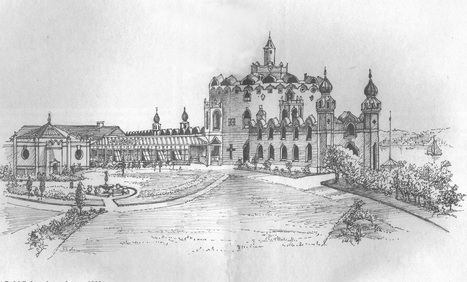

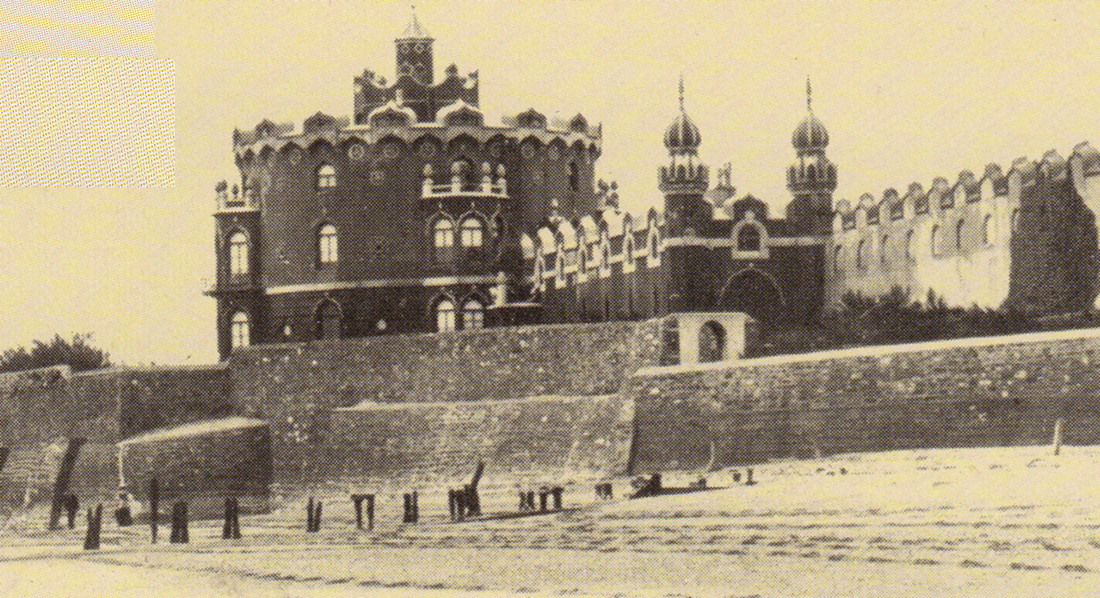

Singer was not responsible for the construction of Redcliffe. This honour belonged to Colonel Robert Smith (1787-1873), a gifted artist and architect who served in India with the Bengal Engineers. He retired from the army in 1832, spent some years in Italy with his wife and young family, before returning to England in 1850. Although born in France, he had brought up in Bideford and had a sister still living in Torquay, which is presumably why he chose to settle in Devon. He designed Redcliffe himself in 1852 and the mansion was built in stages between 1855 and 1864.

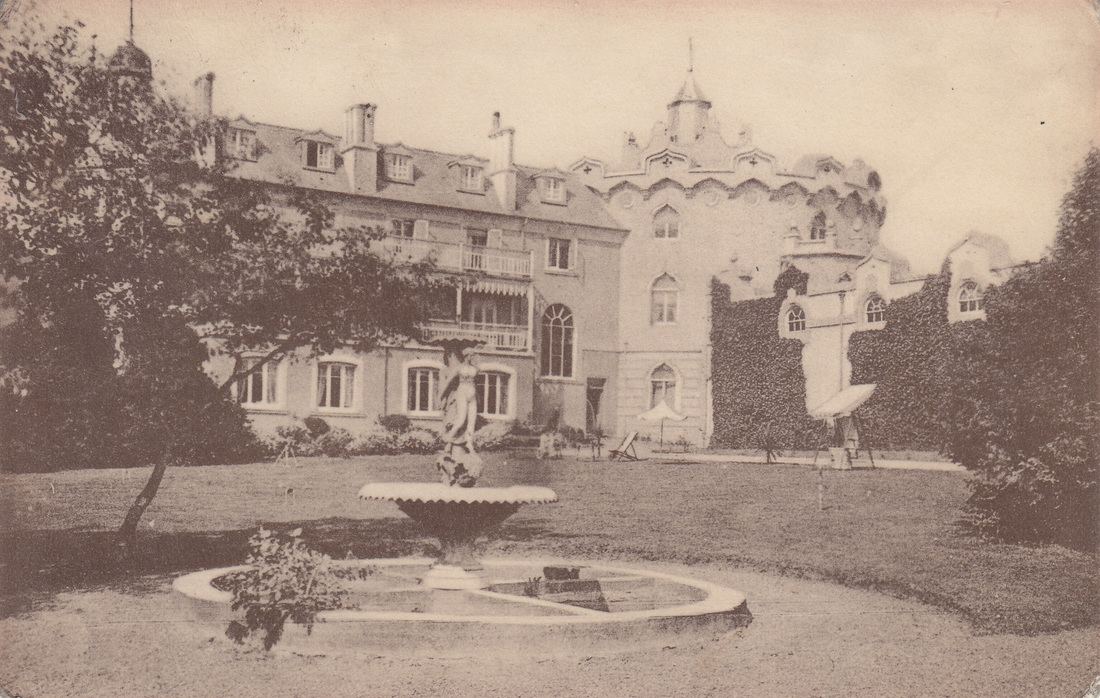

It was a magnificent building, with 23 bedrooms, a conservatory, billiard room, and an underground plunge bath by the sea that was reached by a subterranean tunnel from the house. Redcliffe Castle, as it was called, sat in five acres of gardens that were filled with rare plants Smith had collected from around the world.

It was an enormous building for an elderly man to live in alone, but Smith also built himself a vast chateau near Nice in France. He did not have long to enjoy either property, dying on 16 September 1873. Redcliffe passed to his estranged son, Lieutenant Robert Claude Smith of the Bombay Calvary, but financial problems forced him to sell the house and all its contents in 1877.

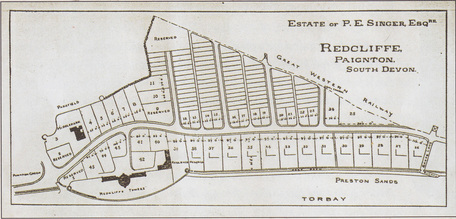

At this time Paris Singer was, of course, only ten years old, and his vast fortune was administered by trustees. The Redcliffe Estate was an attractive buy, because it allowed the trustees to extend Singer’s Fernham estate all the way to the seafront, linking it with other land purchases between Oldway Road and Marldon. After buying Redcliffe, the trustees erected the sea wall that runs along Preston Beach, as well as laying out Marine Drive.

Paris Singer married Lillie Graham in 1887 and ten years later the Paignton Echo records the couple hosting a fundraising bazaar for the local Methodist Church at Redcliffe Towers. During this time the house was rarely occupied, and only opened during the summer months for events such as bazaars and flower shows. In January 1900 Singer had the building converted into a convalescent hospital for soldiers wounded in the Boer War. According to the Paignton Echo, this was done on behalf of Paris by his brother Washington Singer. Paris Singer’s real interest lay in developing the sea front, and in 1904 plans were drawn up for fourteen houses to be built along the front of Preston Green, with another seven houses in the grounds of the Redcliffe itself. (below)

Singer had sold Redcliffe Towers in 1902, and two years later it opened as the 100-bedroom Hotel Redcliffe, touted as ‘The Finest Health Resort in Devon.’ With its opulent, eastern furnishings, oak panelling, stables, electric lighting and panoramic views of Torbay, it offered luxurious accomodation and dining for Paignton’s growing number of visitors.

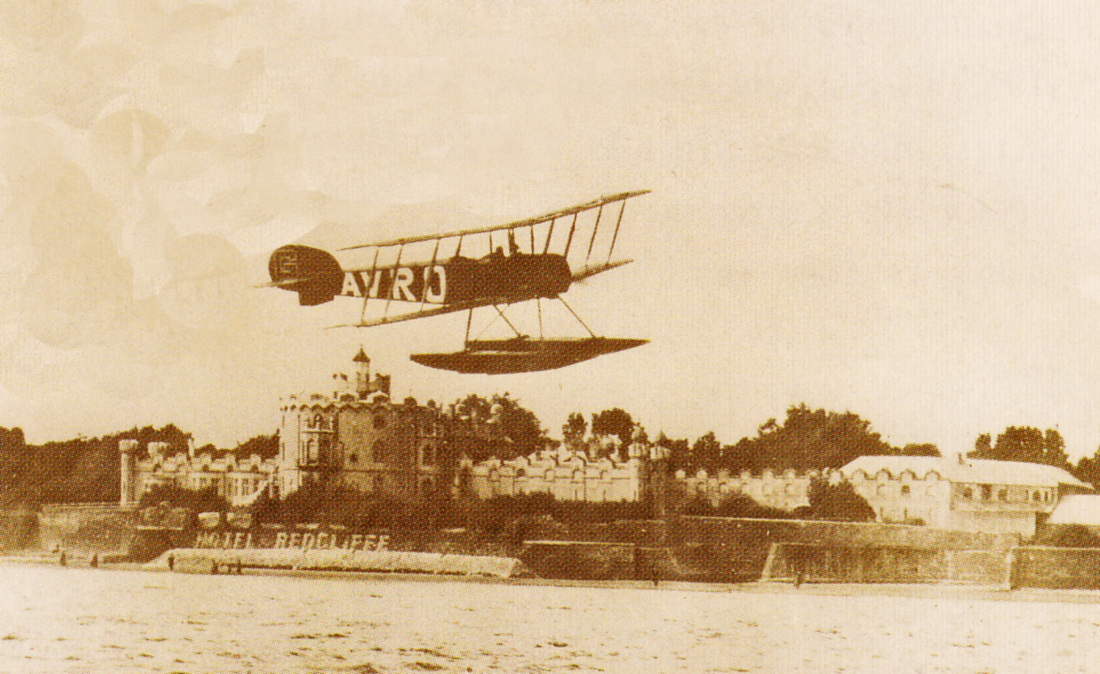

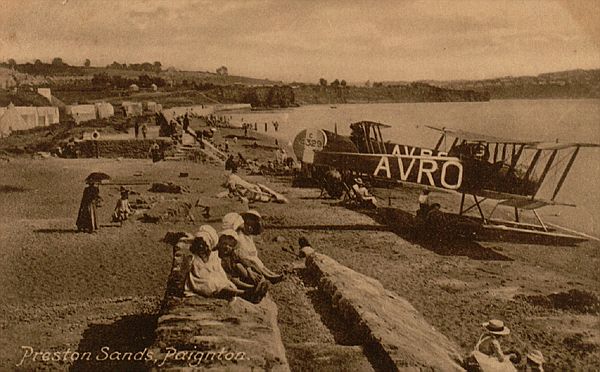

Singer’s grand plans for the sea front were never implemented, and in February 1913 he sold Preston Green to the local council. He retained a small patch of land adjacent to Redcliffe on which he had earlier built an aircraft hangar for storing his two Avro seaplanes. Two months after the sale, Isadora Duncan’s two children drowned in the Seine. The lovers finally separated in 1917.

After the end of the First World War, the seaplanes were used as a visitor attraction, with pilots such as Captain R.L. Truelove offering flights around the bay for the price of 25 shillings. Maybe readers with aeronautical expertise can tell me whether the plane above is an Avro 501, 504 or 510?

In 1919 Paignton Council paid Paris Singer £650 for the hangar, as they wished to develop Preston Green as a pleasure ground. During the early 1920s the area was laid out with bathing huts, tennis courts and a promenade. The hangar was leased out to an aerial mapping firm, but was eventually demolished just before World War Two and replaced with a beach cafe.