Litanies are sets of prayers arranged in the form of a list of petitions, usually sung or chanted by cantors, to which others provide responses. These vary according to the nature of the petition: the name of saint invites the response Ora pro nobis (Pray for us), a general prayer has the reponse Te rogamus, audi nos (We ask you to hear us), while reference to some evil or misfortune – such as ghosts and ghoulies – requires the response Libera nos, Domine (Deliver us, Lord.) In the traditional litany of saints, these calamities include omni malo (all evil), omni peccato (all sin), insídiis diaboli.(the devil’s wiles), fulgure et tempestate (lightning and storm), a flagello terrae motus (earthquake), a peste (plague), fame et bello (famine and war)…etc. There’s nothing here resembling the contents of the Cornish litany. One explanation for this is that it was a local and perhaps unauthorised ritual, one that was used orally and was never recorded in a liturgical book. Some have claimed that it dates back to the 14th or 15th centuries, but such prayers would then have been in Latin, and the absence of any textual record for several hundred years – linking Pre-Reformation usage to a vernacular translation – is hard to comprehend. Tracing the origins of this phrase has proved far harder than one might have imagined. ‘Long-leggety beastie’ sounds like a distinctively Scottish pronunciation, and indeed in the anthology A Beggar’s Wallet (Edinburgh & London, 1905), edited by Archibald Stodart Walker, there is a contribution by Hugh Munro Warrand which is prefaced with a ‘Scots’ version:

Frae ghosties and ghoulies, long-leggetie beasties,

And things that go bump in the night,

Good lord deliver us.

– From a quaint old Litany

However, the fact that only the first word is distinctively Scots suggests to me that this ‘quaint old Litany’ was merely an attempt to ‘Scotticize’ a phrase which had been acquired from some other source. A few years later James Withers Gill, a former colonial administrator who helped catalogue the African collections in Exeter’s RAMM, published a scholarly article on ‘Hausa Speech, Its Wit and Wisdom’ in the Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 1, No. 2 (1918), p.46, in which he remarks casually of the inhabitants of Hausaland in the Sudan: ‘To a people nourished on mystery who, in spite of their fatalistic creed, believe in genii, ghosts, goblins, and those terrific things that “go bump in the night”, protective charms are eagerly sought for.’ Again, the phrase is cited without any explanation, as if the author regarded it as commonplace.

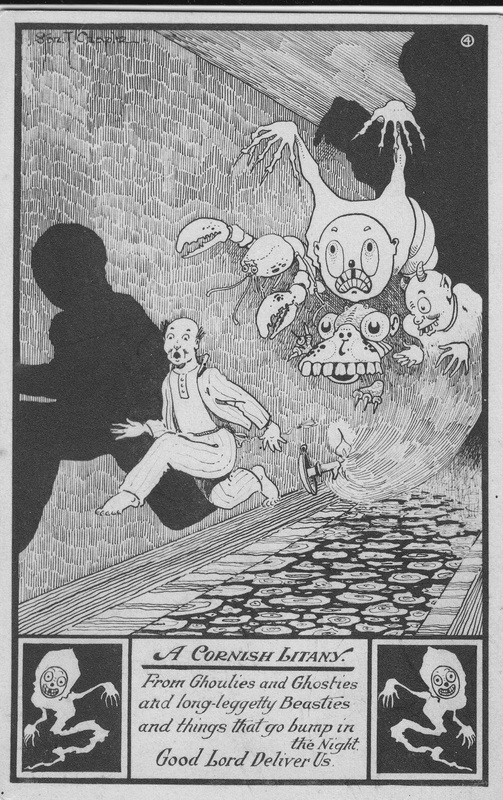

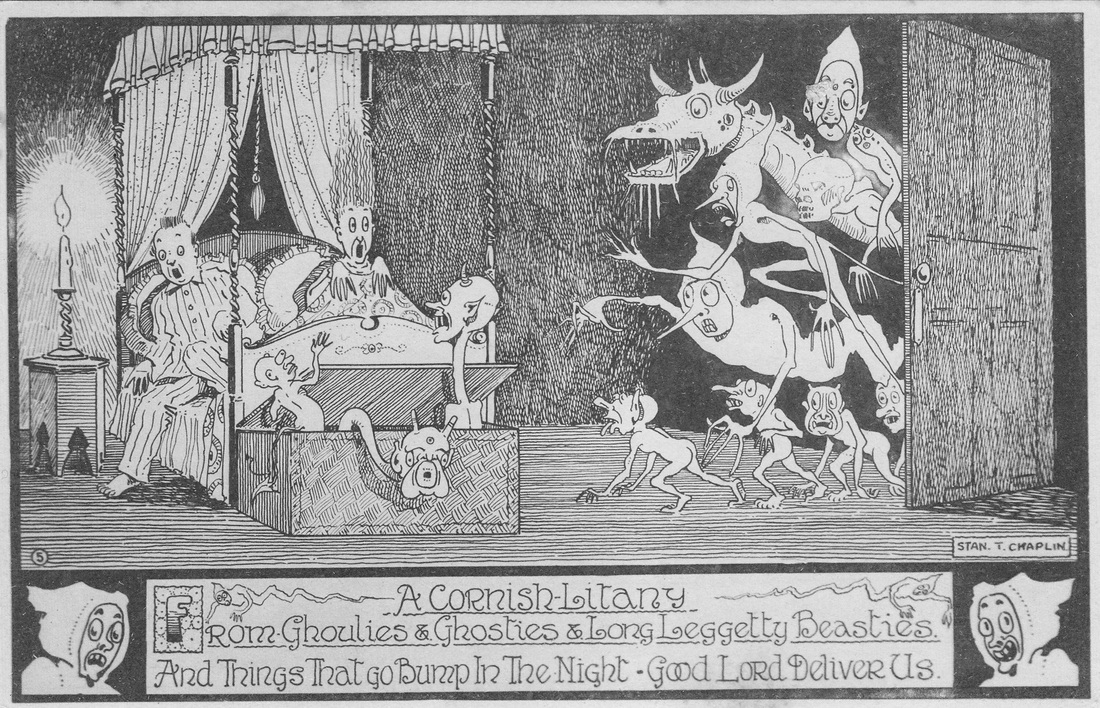

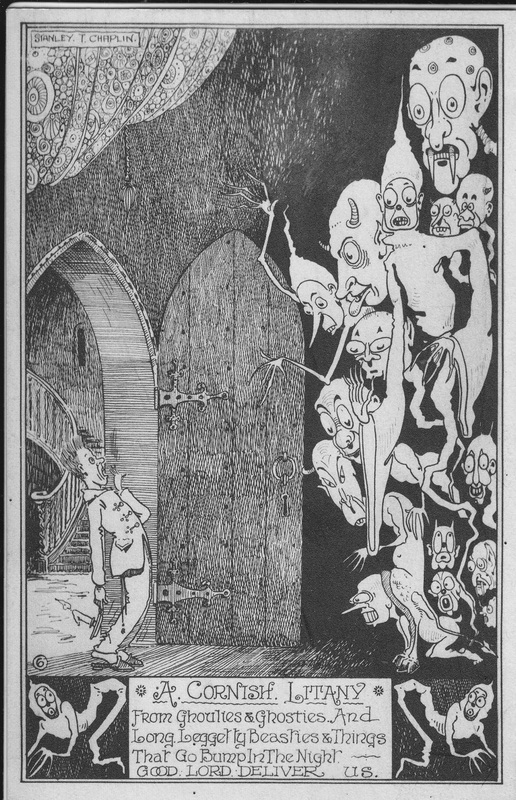

Then, eight years later, Francis T. Nettleinghame published his Polperro Proverbs & Others (Polperro Press for the Cornish Arts Association, 1926) in which he describes the thriving pokerwork industry in Polperro. Pokerwork, or pyrography (“fire-writing”) involves using heated tools to burn designs into wooden objects and craftworkers in Polperro were doing particularly well selling products that featured ‘the Cornish or West country litany.’ The artwork for these wares was undertaken by Arthur Wragg, rather than Chaplin.

That’s really the limit of my knowledge, but an American collector named Debra Meister has done a great deal of research and self-published a book, A Litany…Cornish and Otherwise, which is now in its third edition. I haven’t seen the book yet, but may try and pick up a copy soon. Other sources of information include:

Donald T. Matter, ‘The Cornish Litany, a Prayer for All Times’, The McLintock Letter: the quarterly newsletter of the South Jersey Postcard Club. Vol. 11, No.5 (October 2011), pp.1-2

Susan Hack-Lane, ‘A New Look at the Old Cornish Litany’ in Postcard World Magazine (November-December 2011), pp.7-9.