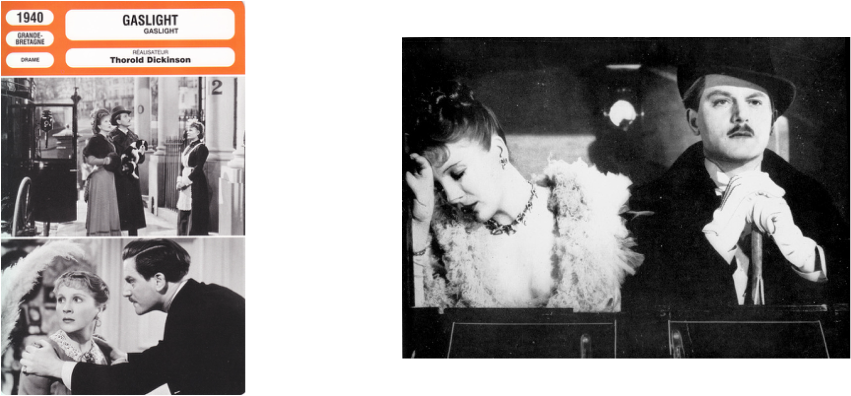

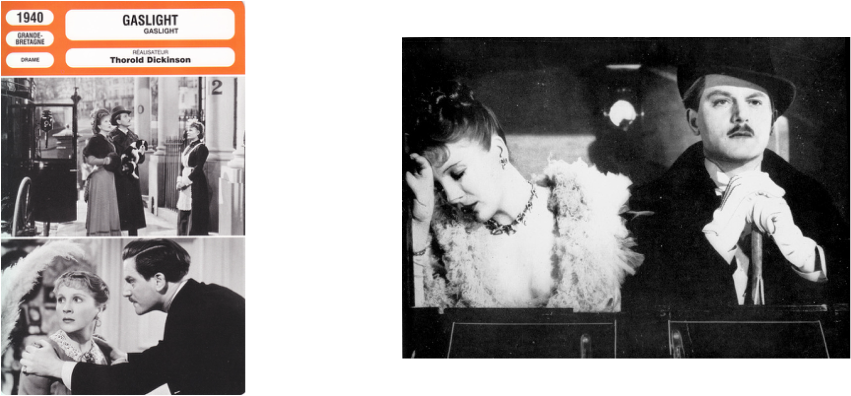

Tonight, as part of their Gothic season, the BFI are screening their newly remastered print of Thorold Dickinson’s neo-Victorian thriller Gaslight (1940), and to mark the occasion I thought I would post a few notes about the film and its Gothic elements – including, of course, Walbrook’s portrayal of the villainous Paul Mallen. All the images below are of items in my own collection, as usual.

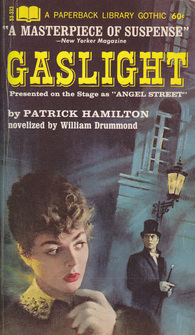

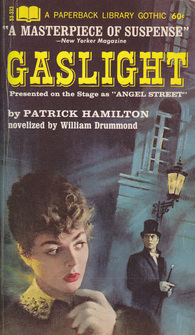

This is the cover of the first edition of William Drummond’s novel, published in the Paperback Library Gothic series in September 1966. The notes on the back cover hammer home the publisher’s belief in the story’s Gothic credentials: “The Greatest Gothic Thriller of All Time!” a “nerve-shattering novelization of that modern masterpiece of Gothic terror and suspense” and “a genuine candidate for honors in the Gothic field.” The lurid plot synopsis emphasises the classic Gothic themes of a beautiful damsel in distress, an evil house, incarceration and madness –

Bella was trapped in the evil mansion on Angel Street – a helpless victim whose safety and sanity was as uncertain as the flickering gaslight that filled her with horror!

Lying in drugged terror in her bedroom, beautiful Bella suspects that her own husband, sinister Mr. Manningham, is driving her mad. But can she be sure? As she fights the whirlpool of insanity, again and again Mr. Manningham threatens to put her into an asylum.

This picture of Bella shows her looking thoughtful rather than terrified, and it should be noted that Drummond’s characterisation of Bella differs considerably from that seen in the film: in the novel she has received a classical education and has a much more vigorous and inquiring mind. Diana Wynyard’s performance is an exquisite portrait of innocence and vulnerability, which makes her humilation at Mallen’s hands all the more painful to watch.

The following year saw the publication in Britain of this paperback, issued by Arrow Books. Most of the text on the back cover repeats the blurb from the American edition.

The cover picture, like the one above, consists of three key images – the female victim, the male villain, and the fog-shrouded gaslight; it is around this trilogy that the entire story revolves. Although subtitled ‘A Victorian Thriller in Three Acts’, Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play lacks the complex plot twists and revelations that are typically found in 19th century crime mysteries. The suspense is psychological rather than plot-driven, and the film therefore depends heavily upon strong performances from the actors: Walbrook as Mallen, Diana Wynyard as Bella, with support from Frank Pettingell as Sergeant Rough, Catherine Cordell as the vixenish maid Nancy, and Robert Newton as Bella’s cousin, Viscount Ullswater.

Gaslight‘s atmosphere of threat and menace is made more disturbing by the carefully crafted domestic setting, highlighting the contrast between the genteel Victorian household and the murder and insanity that lurk within. In a moment of appalling hypocrisy, Mallen leads the household in family prayers, picking up the Bible to read the opening line of Psalm 127: ‘Except the Lord builds the house…’ It is in fact the dark and violent history of the house that is disturbing both husband and wife; such a troubled relationship between a house’s past and present is another classic trope of the Gothic tradition.

There are many other literary echoes in Hamilton’s Victorian pastiche. The name of Sergeant Rough is probably meant to recall that of Wilkie Collins’ character Sergeant Cuff in The Moonstone (1868) – one of the first detectives in fiction, and an archetypal figure for subsequent detective heroes. Similarities exist between the plot of Gaslight and that of Collins’ earlier novel The Woman in White (1859) – a wicked and avaricious husband exercising despotic control over his wife, concealed identities, falsified family histories, and the incarceration of a healthy married woman in an asylum for “delusions” that are in fact true. Parallels can also be made to Jane Eyre (1847), with Mrs Mallen’s virtual imprisonment in her Westminster townhouse echoing the incarceration of Mrs Rochester’s in the attic at Thornfield. Gaslight shows the absolute power that could be wielded by a Victorian husband over his wife, and it is worth remembering that, until the Married Women’s Property Acts of 1870 and 1882, women like Bella Mallen had no control over their money and property, which were the legal possession of her husband. It is rather ironic that Walbrook was fresh from triumphant performances as wholesome Prince Albert Albert in Victoria the Great (1937) and Sixty Glorious Years (1938), before participating in Hamilton’s attack on the dark side of Victorian masculinity.

Viewers of the film were impressed by Walbrook’s performance, which proved – as one letter-writer in The Picturegoer put it – that ‘he can be as good a villain as hero.’ Lionel Collier, in the same magazine, called Gaslight ‘a piece of Grand Guignol’ and added, ‘Anton Walbrook is brilliant as the merciless, calculating murderer. It is a grim study of the morbid.’

Although we never see Mallen striking Bella, the presence of domestic violence is symbolised by the Punch and Judy show taking place beneath their window in Pimlico Square. The archetypal tale of such domestic cruelty is of course Bluebeard, a legend explicitly cited in the 1944 MGM remake of Gaslight, where Bella (renamed Paula Alquist in the Hollywood version) falls into a conversation on a train with an old lady who is reading a Gothic novel based on the Bluebeard story, and then moves on to relate this to the murder of Paula’s aunt in London. Although there is no ‘forbidden chamber’ at No. 12 Pimlico Square, Bella’s discovery of secret objects – such as the the letters locked away inside Mallen’s bureau – reveal the truth about her husband’s real identity and murderous past, thus placing her life in further danger. As with Bluebeard, she does not save herself but relies on male intervention from outside the house. However, there is a clever twist at the end of the play, when Bella locks herself and Mallen inside the bedroom alone, and throws away the key; now the villain is unprotected, the police are on the other side of a locked door, and he is alone with a madwoman who has fully realised the extent of her husband’s evil…..

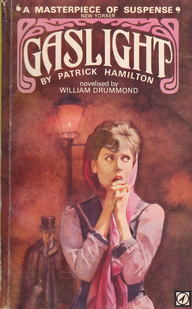

Patrick Hamilton got the central idea for his play – the image of dimming gas lights – from a crime novel written by his brother Bruce Hamilton, To Be Hanged (1930.)

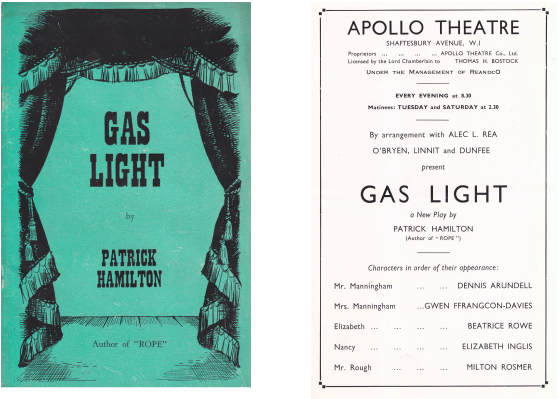

Written during 1937 it was first performed at the Richmond Theatre in Surrey on 5 December 1938, produced by Gardner Davies. It soon transferred to the west end, opening at the Apollo Theatre on 31 January 1939. George VI and Queen Elizabeth were among those who saw the play.

The part of the villainous husband was played by Denis Arundell, who had a small role alongside Walbrook in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp four years later. On 19 March 1939 Arundell and the rest of the cast performed the play before BBC cameras at Alexandra Palace, enabling it to be broadcast live for television audiences (then numbering well under 100,000 households in the UK.)

The play later moved to Broadway, where it opened under the title of Angel Street on 5 December 1941 – two days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Manningham’s role was played by Vincent Price and the production ran for four years, bringing Hamilton considerable wealth. When the MGM film starring Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman was released in Britain it went under the title of The Murder in Thornton Square to avoid confusion with the British original.

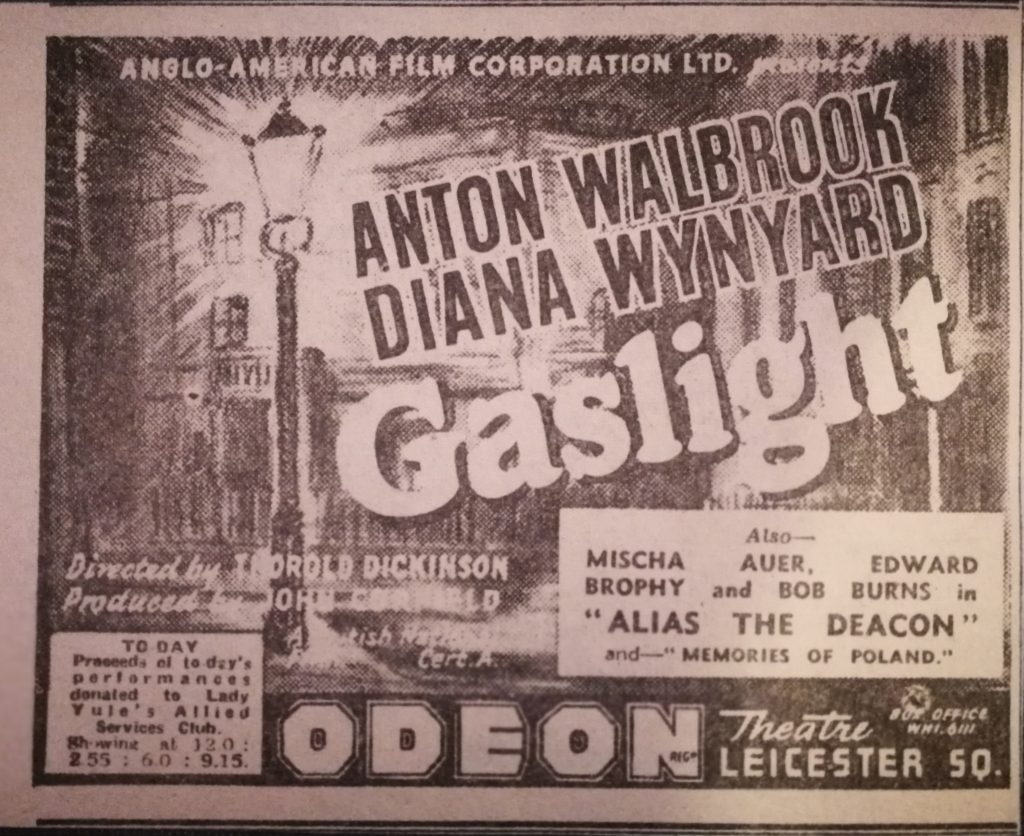

This is an early promotional poster for Gaslight, issued with Kinematograph Weekly magazine in January 1940. The director’s name is given here as Anthony Asquith; within a few days he would be replaced by Thorold Dickinson.

Although I am a huge admirer of Dickinson’s work, I remain curious as to what Asquith would have done with Gaslight. He proved himself a skilled director of theatrical adaptations, but the atmospheric power of some of his early silent films – especially A Cottage on Dartmoor – suggests he could have made something quite special out of Hamilton’s play. In the same year that Hollywood remade Gaslight, Asquith produced a costume drama for Gainsborough Studios – Fanny by Gaslight – which is also set in late Victorian London and features another black-caped villain, this time played by James Mason.

The poor condition of this glass plate is due to its having been discovered on a rubbish dump in Scotland. Someone once suggested to me that it was a beer mat, but the plate is in fact a lantern slide, hand made for the purpose of advertising Gaslight to cinema audiences: the image would have been projected onto the cinema screen prior to another film being shown, in the same way that trailers are now shown. The use of such slides persisted into the 1950s, and even later in some places.

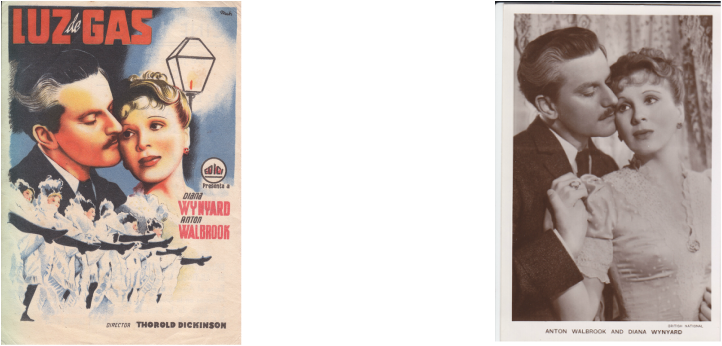

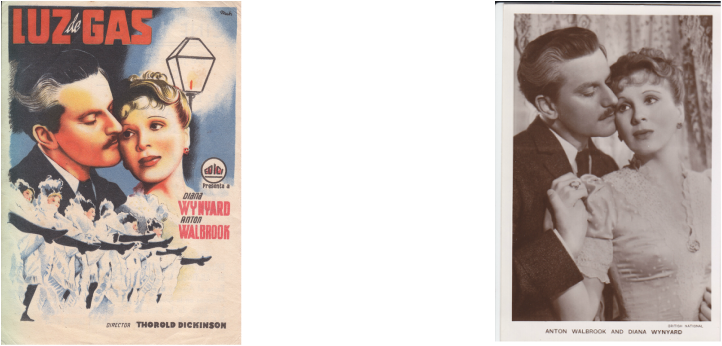

On the left is a Spanish handbill advertising Gaslight at the ‘Cine Victoria’ in Silla. The reverse of the bill promises that the film will deliver ‘Gran emocion!’ and ‘Intenso dramatismo!’, although the promoters obviously thought a picture of can-can dancers would widen the film’s appeal. The image of Walbrook and Wynyard is clearly based on the film still on the right, which was issued as a postcard by Picturegoer magazine.

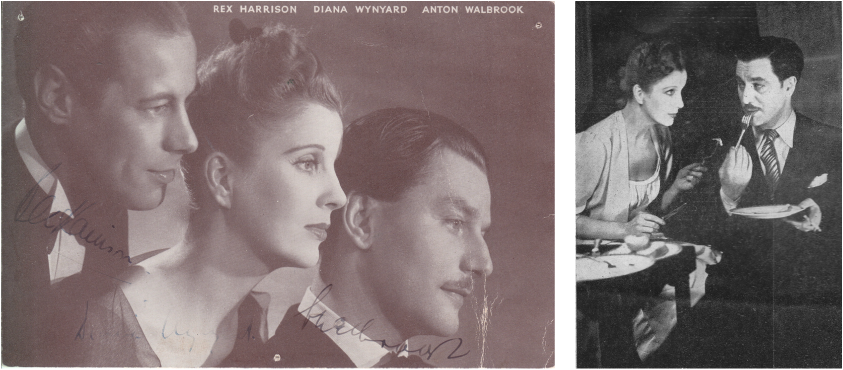

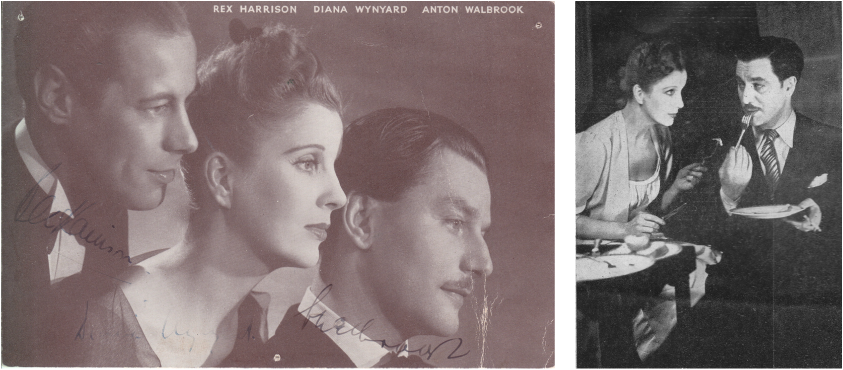

The two actors had already proved their ability to work well together in Noel Coward’s comedy Design for Living, which opened in the West End in January 1939 and ran – at various venues – for twelve months, allowing the two stars only a short break before they began filming Gaslight.

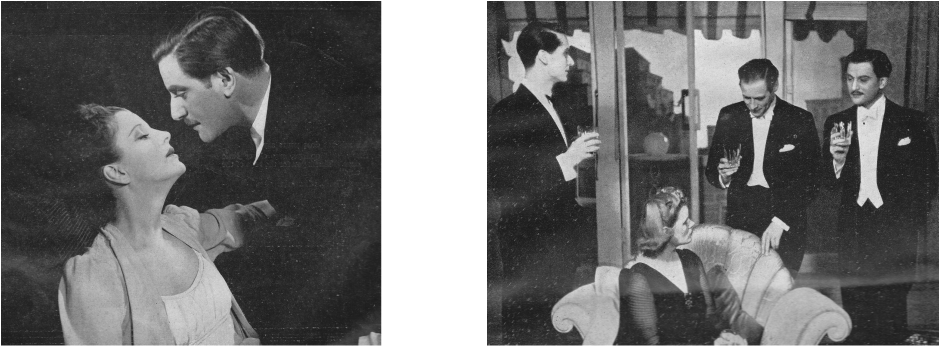

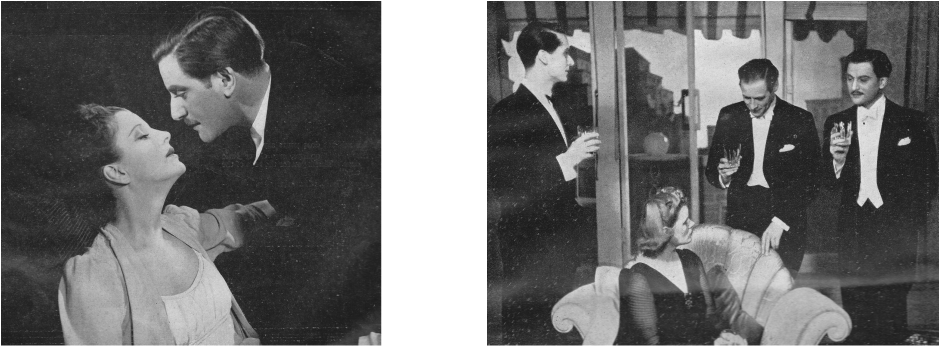

The relationship between Otto (Walbrook) and Gilda (Wynyard) in Design for Living is utterly different from the tortured married life of the Mallens; Coward’s play revolved around a Bohemian menage-a-trois shared with Rex Harrison. Cathleen Cordell, who played Nancy in Gaslight, was another cast member – she played a young newly wed named Helen Carver, seen here on the sofa in a scene from Act III.

Nancy is shown below, greeting the Mallens on their arrival at No.12 Pimlico Square, on this French publicity sheet about Gaslight. Mallen’s flirting with the maid is just another means of tormenting Bella, but it also signifies the power that he holds over the women in his house. His dark, Byronic magnetism is revealed by Nancy’s confession to her master, ‘I always wanted you, ever since I clapped eyes on you.’ Walbrook played very few villains in his career, and the crimes of Captain Suvorin (Queen of Spades, 1949) and Major Esterhazy (I Accuse, 1959) pale alongside the impenitent cruelty of Mallen. It is only at the end, when we see him unkempt and hysterical, oblivious to those around him as he claws at the rubies, that it becomes apparent how much his mind has been damaged by this twenty year obsession. Is the revelation of insanity a punishment for his crimes or a plea for mitigation? In the dark heart of Gothic, such questions are often easier to ask than to answer.