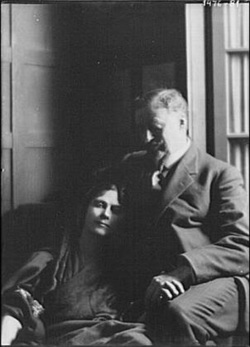

Last week saw the anniversary of the death of Paris Eugene Singer (1867-1932), the wealthy heir to the Singer sewing machine empire whose connections to Devon have long intrigued me. Sometime I might do a more detailed blog post about his properties at Redcliffe and Oldway, but today I thought I’d write about his relationship with dancer Isadora Duncan (1877-1927.) No other individual has exerted such influence upon the world of dance, and her life blended extraordinary accomplishment and appalling tragedy. Her relationship with Paris Singer played a key part in both the both the triumphs and the disappointments.

Her early life contrasted starkly with his. Born Angela Isadora Duncan in San Francisco, the youngest of four children, she was three when their father abandoned the family after a banking scandal. Isadora’s schooling was scant, partly from lack of money, partly from choice. Always a free spirit, her love of dance manifested itself at an early age, but in unusual forms: seeking out deserted beaches or woodlands glades she would dance alone to her own rhythms. The Duncans earned money from music lessons, dance classes and family performances, given by Isadora and her sister Elizabeth with their mother on piano. Between dances their brother Raymond read from Greek classics. As Isadora’s dancing developed, so too did her passion for ancient Greece, influencing her preference for simple robes and barefoot dancing.

Her vision of “the dance” differed from the only two forms then recognised – ballet and music hall – but, needing an entry, she joined Augustine Daly’s theatre company. One tour took her to England where she performed for the first time in October 1897. Unsatisfied, however, she left Daly’s troupe and travelled to Paris.She quickly made her mark in the Parisian salons, including that of the Prince and Princesse de Polignac, frequented by the finest composers and writers. Prince Edmond de Polignac was 30 years older than his wife, Winnaretta Singer, and when he died in August 1901 Isadora had her first brief meeting with the Princesse’s brother Paris Singer.

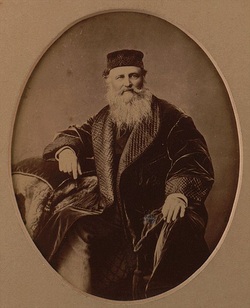

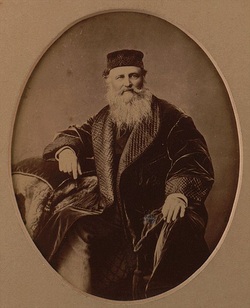

The two siblings were among the numerous children of Isaac Merritt Singer (1811-75), founder of the Singer Sewing Machine Company. An enormously wealthy man, Isaac was nonetheless of humble origins and like Isadora, loved the stage. He spent many years acting with groups of itinerant players, combining this theatre work with his growing interest in sewing machines. He founded his own troupe, “The Merritt Players,” with money received from a machine patent in 1839. Business prospered by his brilliant production and marketing methods. Using his theatrical flair for showmanship and advertising, Singer popularised his machines and made them easier for households to obtain. Sales boomed and Singer factories opened across the world to meet the demand.

This physical drive and charisma also resulted in a complex domestic life. Over three decades, Singer fathered around two dozen children by five different women. Disgraced by a bigamy charge in 1862, he left America for Europe, only to abandon his then-wife for Isobelle Eugenie Boyce Somerville in Paris. They married in June 1865. Isobelle was a well-known society beauty, whose face – it is said – was used by French sculptor Auguste Bartholdi as his model for the Statue of Liberty.

Named after the city where he was born on 20 November 1867, Paris Eugene Singer was Isaac’s third son and (probably) his 23rd child. When Paris was two, the Singers fled to England to escape the Franco-Prussian War. Isaac purchased Fernham estate in Paignton, near Torquay, where the foundation stone of a new 115-room residence named Oldway was laid in May 1873. A circular pavilion was also erected, with banqueting hall, stables and pool, amid twenty acres of landscaped gardens. Just as Oldway’s interior neared completion, Isaac Singer died on 23 July 1875. He was buried in Torquay a week later, leaving a fortune of around $13,000,000.

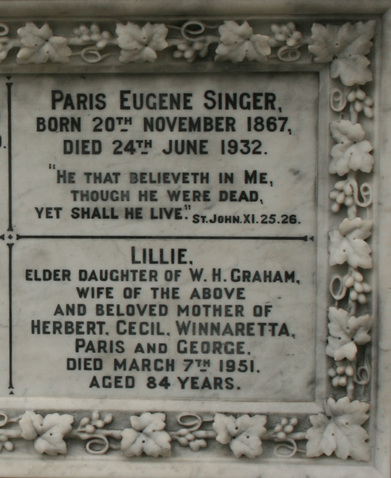

Although orphaned at the age of seven, Paris Singer inherited much of his father’s character along with a weekly income of $15,000 from interest alone. Standing at 6’3” with golden curls and beard, he cut a striking figure. After studying medicine, chemistry and engineering at Cambridge, he eloped with his mother’s maid Henriette Marais. Their marriage was annulled, and in 1887 he married Australian beauty Lillie Graham by whom he had five children.

After coming of age he bought out his brother Washington Singer’s interests in Oldway. Over the next 25 years the mansion underwent a series of lavish decorations and extensions, with the ceiling painting alone taking six years to complete. The opulent blend of coloured marble, gilt panelling, mirrors and parquet floors remains stunning to this day. Passionately Francophile, Singer modelled his reconstruction on the Palace of Versailles. It was therefore fitting that Singer first met Isadora Duncan in Paris.

She was by now an international figure, based in Germany and known throughout Europe from her performances and lectures, with a reputation as a passionate and unconventional spirit. She had toured Hungary, Italy and Russia as well as her beloved Greece, where she delved deep into archives and libraries to seek out musical manuscripts. She learnt German and read philosophers such as Nietzsche in their original language.

In December 1904 she met actor and designer Edward Gordon Craig (1872-1966) in Berlin. Despite Craig being married, they fell in love and Isadora bore him a daughter named Deirdre in September 1906. When her Grünewald dance school had to close in 1908, she relocated to Paris where she performed triumphantly throughout January and February 1909 at the “Gaité-Lyrique” theatre.

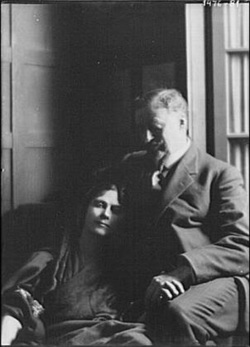

It was after one of these shows that Paris Singer appeared at Isadora’s dressing room with the words, “I have come to help you. What can I do?” With riches like his, there was a great deal he could do for her. In her autobiography Isadora called him “Lohengrin,” one of the Knights of the Round Table: but she would learn that this gallant benefactor’s support came at a price. In the meantime, with Singer’s marriage on the rocks, they embarked on a passionate affair. In September 1909, while in Venice, she found she was pregnant.

After cruising the Nile they returned to France for the birth of Patrick Augustus on 1 May 1910. That summer was spent in Devon where a huge ballroom had been built at Oldway. Despite his extravagant gifts, Singer’s failure to share Isadora’s vision was a frequent cause of friction. Like many wealthy men, he was accustomed to having his own way; there were storms and sulks when his impulsive, temperamental lover danced to her own tune. The romance continued however, and in 1912 Singer bought her a property overlooking the Seine – scene of the greatest tragedy of Isadora’s life.

On 19 April 1913 Singer and Duncan met for lunch in Paris. Later, as the chauffeur was driving the two children home with their governess, he stalled and got out to crank the engine. The car restarted on a slope and – before he could get in – moved off, picking up speed before crossing the Boulevard Bourdon and plunging over a grassy bank into the Seine. Despite desperate attempts by bystanders, all three occupants drowned.

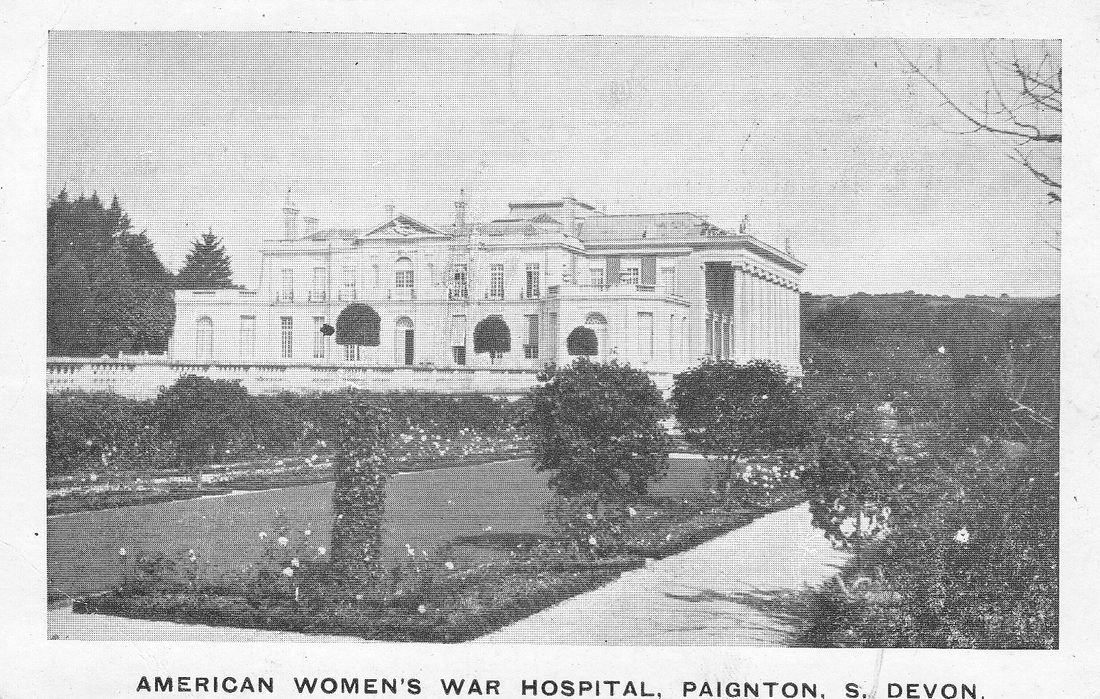

Isadora’s grief was beyond words. Probably desperate for another child, she fell pregnant by a young Italian lover, but the infant died in August 1914 while the citizens of Paris prepared for war. Isadora gave her newly-opened school to the Dames de France for use as a military hospital. Singer had Oldway converted for the same purpose, repeating what he had done 14 years earlier with Redcliffe Towers in Paignton, which housed convalescent soldiers after the Boer War. Oldway became the American Women’s War Relief Hospital, personally financed by Singer and well-respected: Queen Mary visited in November 1914 just as Isadora sailed for New York.

When she returned penniless after travelling around Europe and South America, Singer had no difficulty bailing her out again: his secretary at this time, Allan Ross Macdougall, received $1000 a week. (He was later Isadora’s first biographer.) Singer’s inability to appreciate her art led to their final quarrel in March 1917 after she refused, in public, his gift of Madison Square Garden.

His relationship with Isadora over, Singer divorced his wife in 1918 and married Joan Balsh, senior nurse of the military hospital at Oldway. For tax reasons he took American citizenship and began developing property around Florida – there is still a Paris Singer Island, off Palm Beach. His ambitious plans were shipwrecked in the late 1920s, and with heavy losses and lawsuits, he returned to Europe. Although Singer lost a lot of money, he always had plenty to lose. He might not have lost Isadora had he not been so determined to possess her.

By this time she had been lost to the world altogether, dying, like her children, in another bizarre motoring accident after a life of further twists. She broke with Singer the same week as the Russian Revolution, on the night of which she “danced with a terrible fierce joy.” Ever-sympathetic with revolutionary spirits, she moved to Moscow at the suggestion of a Russian diplomat who saw her dance in London. Her two years in the Soviet Union included a short, disastrous marriage to Russian poet Sergei Esenin. His drunken rages and violent behaviour hampered her European tour in 1923, foreshadowing the end of their marriage and Esenin’s hospitalization (and untimely death) in a Soviet mental asylum.

Early in 1925 Isadora moved to Paris, where she began writing her memoirs, still receiving anonymous financial support from Singer. She died in Nice on 14 September 1927, killed when her scarf caught in the wheels of a moving car. Her ashes were placed in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, following a funeral attended by thousands.

Paris Singer outlived her by less than five years, dying in London on 24 June 1932. He was buried in the family vault at Torquay.

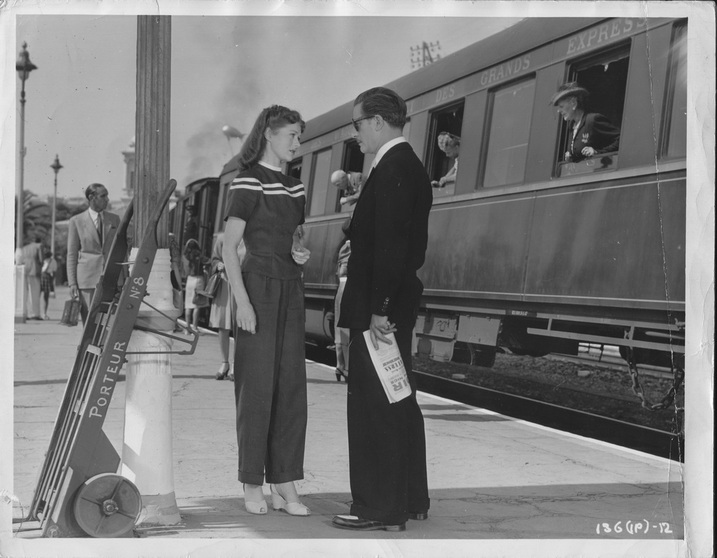

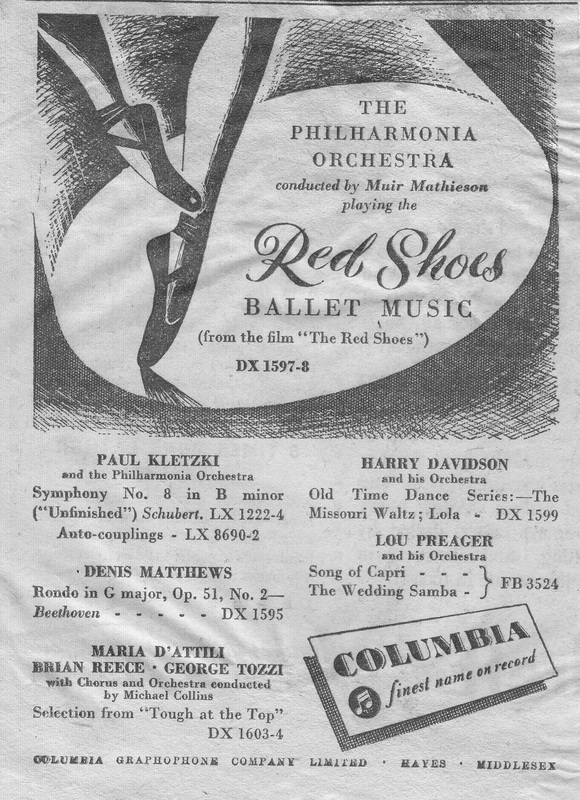

On this day, sixty five years ago, The Red Shoes received its world premiere at the Gaumont Haymarket and Marble Arch Pavilion. Both cinemas were part of the Gaumont chain, which was then owned by Rank – the decision to hold the premiere here, rather than at the prestigious Odeon in Leicester Square, was a mark of Arthur Rank’s lack of appreciation for the film. It nonetheless proved highly popular with British audiences – and international ones too, as these Spanish posters indicate. To celebrate today’s anniversary, I’m posting a series of film stills – in black and white, alas, rather than glorious Technicolour.

On this day, sixty five years ago, The Red Shoes received its world premiere at the Gaumont Haymarket and Marble Arch Pavilion. Both cinemas were part of the Gaumont chain, which was then owned by Rank – the decision to hold the premiere here, rather than at the prestigious Odeon in Leicester Square, was a mark of Arthur Rank’s lack of appreciation for the film. It nonetheless proved highly popular with British audiences – and international ones too, as these Spanish posters indicate. To celebrate today’s anniversary, I’m posting a series of film stills – in black and white, alas, rather than glorious Technicolour.

Well, it’s almost time now to close down the exhibition, ‘Anton Walbrook – Star and Enigma’, which has been running at the Bill Douglas Centre for the History of Cinema and Popular Culture, University of Exeter , since 5 March 2013.

Well, it’s almost time now to close down the exhibition, ‘Anton Walbrook – Star and Enigma’, which has been running at the Bill Douglas Centre for the History of Cinema and Popular Culture, University of Exeter , since 5 March 2013.