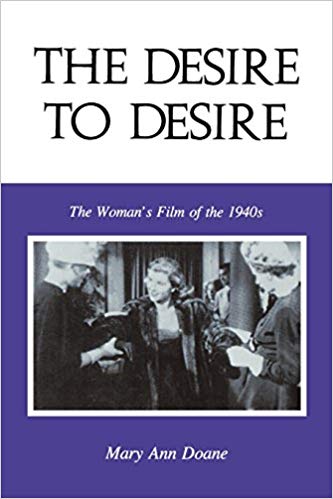

The existence of the genre of the ‘woman’s film’ is a challenging one for feminist critics such as Doane, for while these films portray women in stereotypical feminised roles – mothers, lovers, hysterics, invalids or victims – they were hugely popular with female cinema-goers, who evidently enjoyed the films and identified (in some way) with the onscreen depictions of women’s experience. As a feminist, theoretical critic and psychoanalyst, Doane seeks to explain the anxieties underpinning these films and the ways in which filmmakers tried to get audiences to identify with the psychological behaviour of the screen characters.

‘‘before she dies she becomes pure gaze’ (p.122)

Vivien Leigh in Waterloo Bridge (LeRoy, 1940)

Inevitably she is building on Laura Mulvey’s groundbreaking essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ which was published in Screen journal in 1975. (It was later revised for Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, edited by Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (New York: Oxford UP, 1999) pp. 833-44, which would provide a good background read for anyone approaching this topic.) Mulvey coined the term ‘male gaze’ to discuss the concept of ‘scopophilia’, the pleasure taken in gazing at the passive female as an object – a notion she pursued using the language of voyeurism and fetishization. These are also terms employed throughout Doane’s book, for even though the idea of the women’s film might suggest a ‘female gaze’ – women in the audience watching women on screen – it is important to grasp that Mulvey’s male gaze had three perspectives – that of the filmmaker, the screen character and the viewer – and was never intended to suggest binary distinctions between biological gender. As Doane makes clear, most of these ‘women’s films’ were made by men and reflect typically masculine anxieties about female agency during the wartime period; the way in which women were portrayed onscreen – she argues – was in keeping with a particular agenda that sought to increase female identification with passivity, suffering and neurosis.

‘the compatibility and substitutability of feline and female’ (p.51)

Simone Simon in Cat People (Lewton, 1942)

By choosing to focus on woman’s films in the 1940s Doane lines up a marvellous array of classics movies with some of the era’s greatest actresses. We have Bette Davis in The Letter (Wyler, 1940) and Beyond the Forest (Vidor, 1949), Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce (Curtiz, 1945), The Locket (Brahm, 1946), Humoresque (Negulesco, 1946) and Possessed (Bernhardt, 1947),Olivia de Havilland in To Each His Own (Leisen, 1946), Barbara Stanwyck in Stella Dallas (Vidor, 1937) and so on. Several of Max Ophuls’ films, including Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948), Deception (also 1948) and The Reckless Moment (1949) are included, as is Gaslight (the Cukor 1944 adaptation, rather than the Walbrook one, alas) Secret Beyond the Door (Lang, 1947), Suspicion (Hitchcock, 1941) and many, many others – including Gene Tierney in Leave Her to Heaven (Stahl, 1946) just to prove the Forties weren’t entirely monochrome. So what does the author have to say about these films?

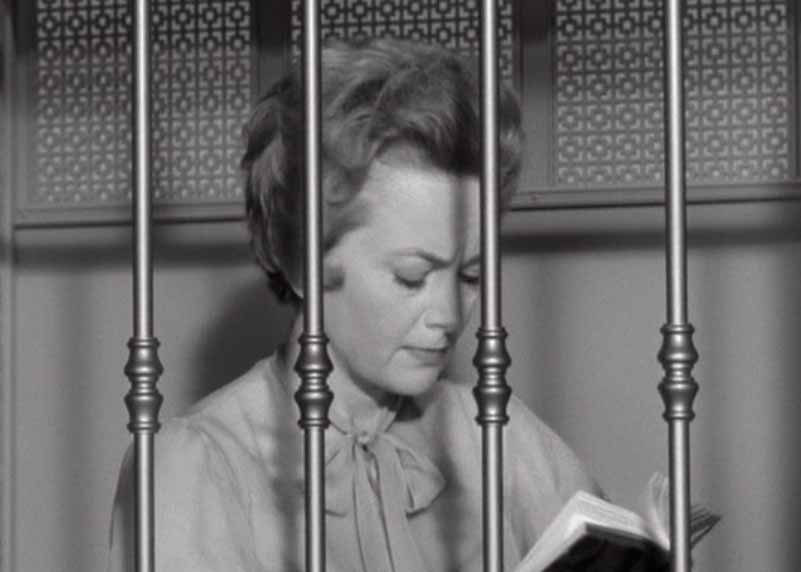

‘her daydream of happiness turns into a nightmare when she is unable to say “I do”‘ (p.148)

Dorothy McGuire in The Spiral Staircase (Siodmak, 1946)

At times, frankly, what the author wishes to say is not immediately clear, which is (sadly) perhaps what one should expect from a psychoanalytical theorist. Viewers who have watched these films many times and learned to relish Ophuls’ gorgeous cinematography, appreciate Tourneur’s masterly use of sound – or thrill to the soaring beauty of the music scores composed by Waxman for Rebecca or Newman for Leave Her to Heaven – may well feel disappointed by the downright ugliness of sentences such as ‘It is as though the historical threat of a potential feminization of the spectatorial position required an elaborate work of generic containment olation’ (p.2) that form much of the prose here. This is a shame, as the author has a great deal of perceptions observations to make, and readers who manage to persevere with the difficult language may find the author’s insights valuable in reshaping attitudes towards this ‘golden age’ of movies.

For Doane, popular terms for women’s films such as ‘weepies’ and ‘tearjerkers’ indicate the narcissistic nature of female spectatorship and its over-identification with the emotional states portrayed onscreen. In most of these movies, women are only allowed to feel a passive form of sexual desire, and those who express – or worse still, act upon – an active desire are generally punished. The author makes a forceful argument not only about the extent to which these films rely upon, and exploit, a range of psychical conditions associated with stereotypical femininity, but also the ways in which the actual visual imagery of these films and its effects are deployed in enforcing these constructs, and just how deeply these symbols are ingrained within the subconscious of both the watchers and the watched.

‘the victim of desires which exceed her social status’ (p.75)

Barbara Stanwyck in Stella Dallas (Vidor, 1937)

One trouble with the author’s emphasis on conceptual theorizing is that it seems to treat both the women in the cinema audience and those on the screen as ciphers of ideological concepts rather than real human beings. To me, the language of this sort of critical discourse is so far removed from everyday experience that it comes across almost as dehumanizing – achieving precisely the opposite effect of that intended by the author. Those seeking to learn more about women’s experience of cinema-going around this time might find Lisa Stead’s Off to the Pictures: Women’s Writing, Cinemagoing and Movie Culture in Interwar Britain (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2016) far more engaging and convincing, because it is so deeply rooted in real voices and material ephemera.

This is the penultimate post in this summer’s #ClassicFilmReading challenge