Monthly Archives: June 2015

LEAVES from a commonplace book

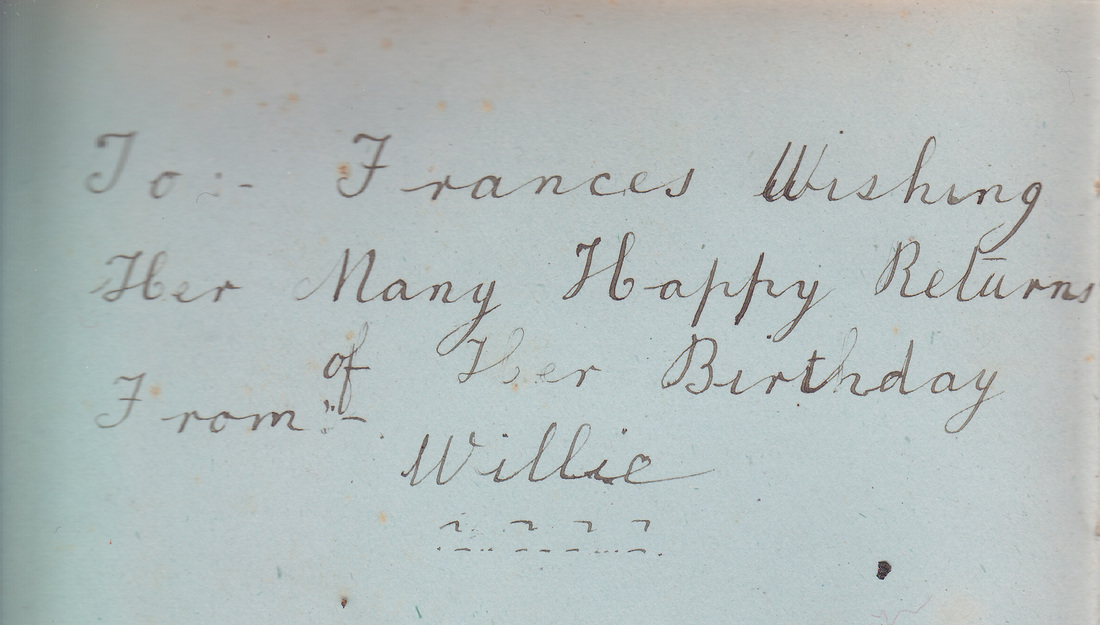

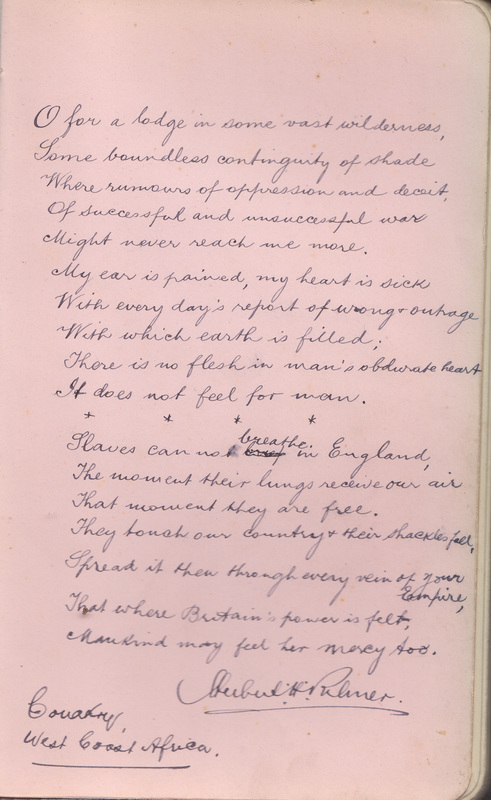

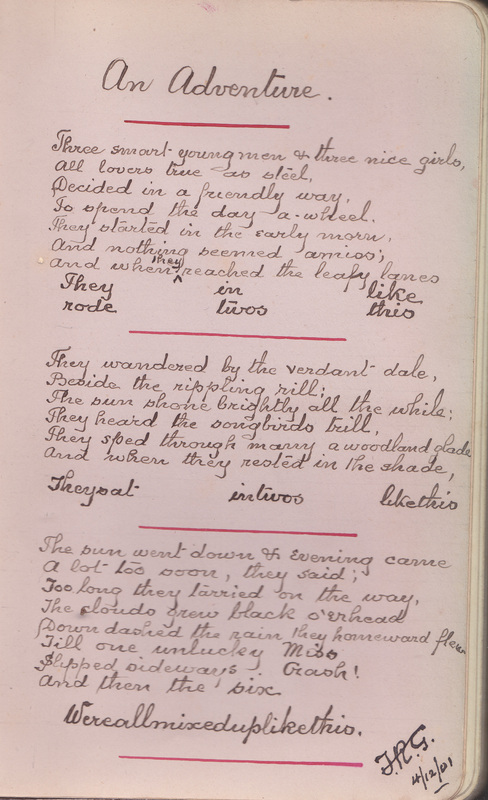

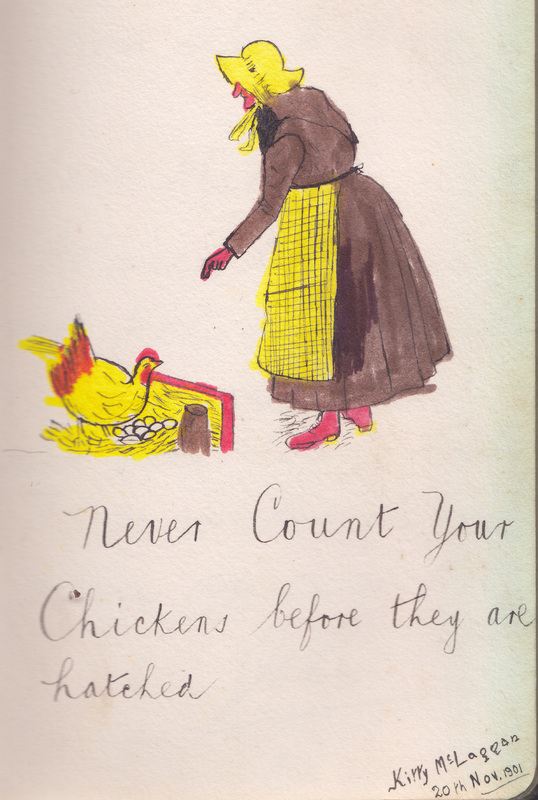

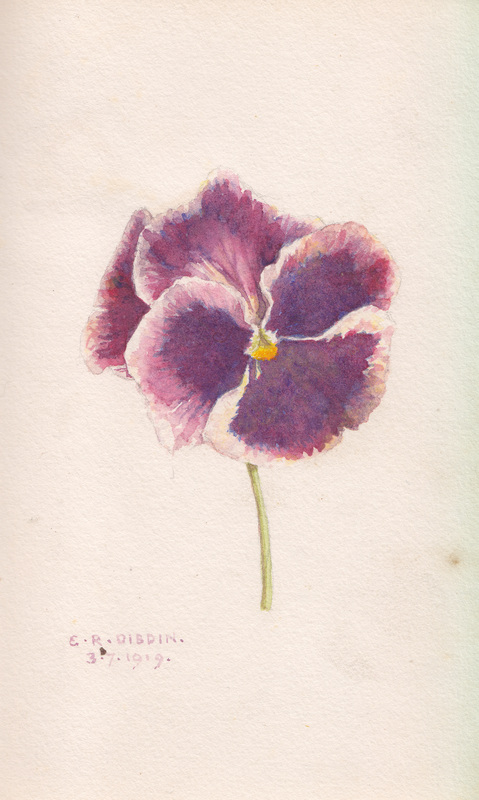

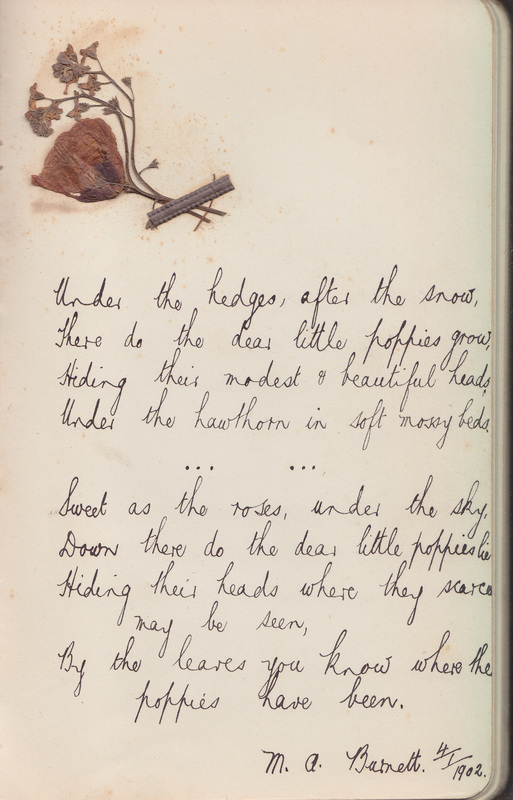

Some of the items in my collection are what one might call high-end artefacts – beautifully-crafted and formally-produced, such as limited edition fine prints or bound volumes. However elegant and precious these might be, I often find myself far more attracted to – and excited by – the odd little vernacular trinkets found at the other end of the scale: hand-written postcards, personal ephemera, amateur photographic montages or scrapbook compilations. Objects such as these were created without any interest in commercial value or posterity, and in addition to their sense of honesty and charm, they often provide a window into how our ancestors amused themselves in private.

Compiling commonplace books was a popular pasttime well into the 20th century, and one might argue that contemporary online practices such as blogging and website such as Pinterest are a continuation of the same impulse. Commonplace books are compilations of quotations, useful passages from books, epigrams and so on, copied out into one’s own notebook and often organised thematically or by the addition of an index or other keys, They developed from the medieval florilegium or ‘gathering of flowers’, in which the scribe would select what he regarded as the wisest texts from earlier writers – just as a bee extracts nectar from the most attractive flowers – and arranged them under thematic headings. Although there was always this tradition of serious, intellectual self-improvement – the philosopher John Locke published his A New Method of Making Common-Place Books in 1706 – there was also a more light-hearted approach that saw compilers decorate their favourite quotes with colourful illustrations, cartoons or floral emblems. Sometimes others would be invited to write their own texts or verses onto the pages, producing some overlap with autograph and visitors’ books. Such books might well be compiled as someone was about to get married or leave the country: it would be an opportunity for friends and family to choose appropriate words of wisdom or poetry, to which they could add their own messages.

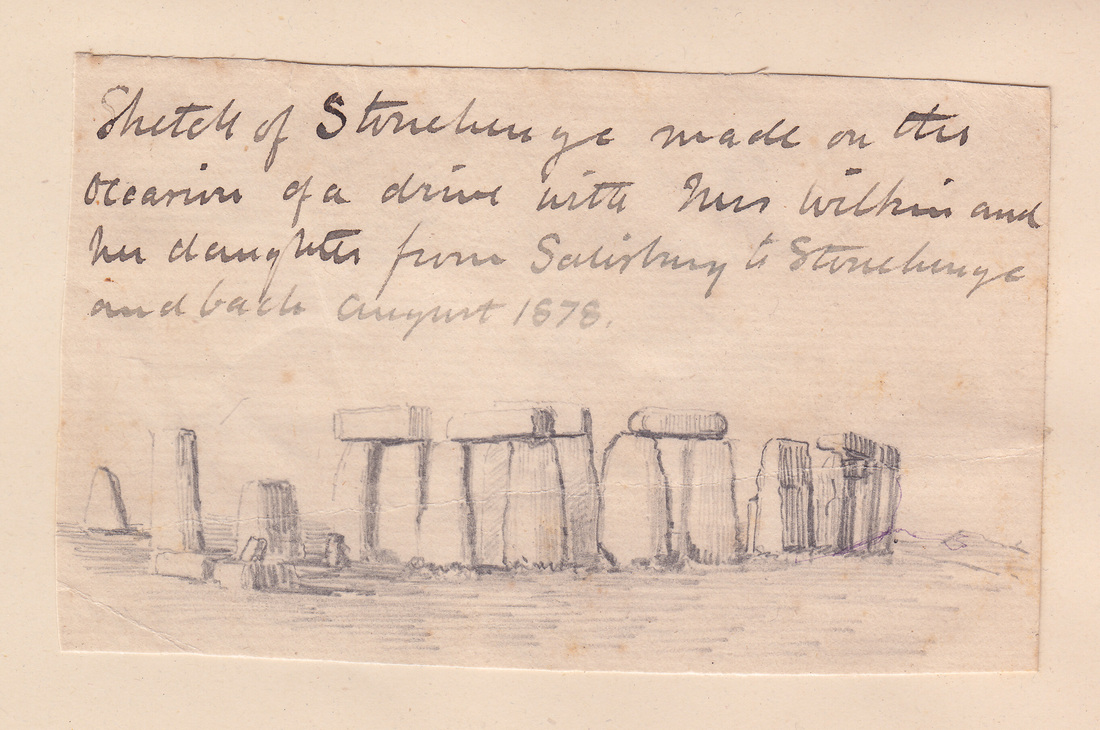

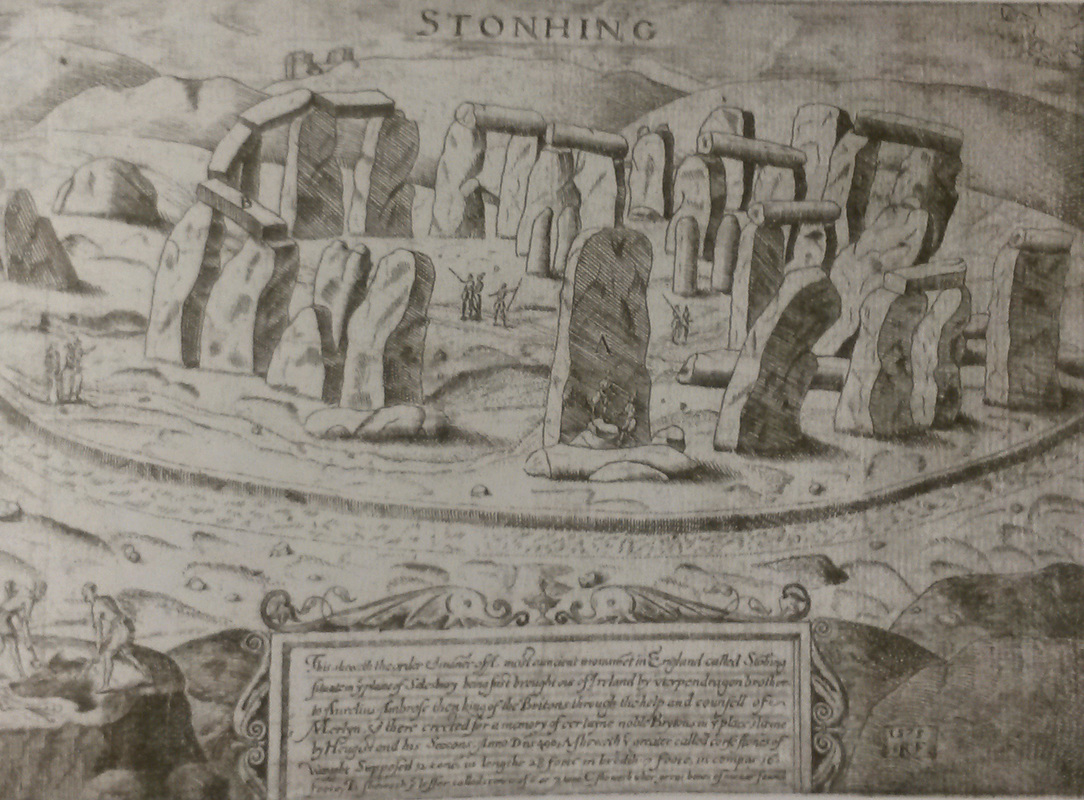

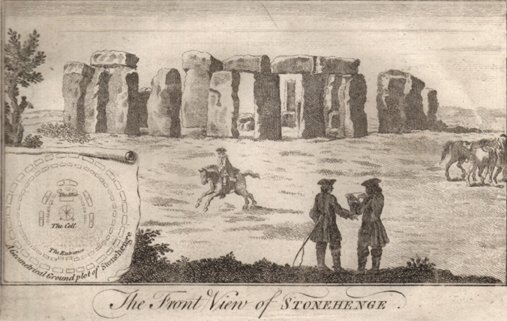

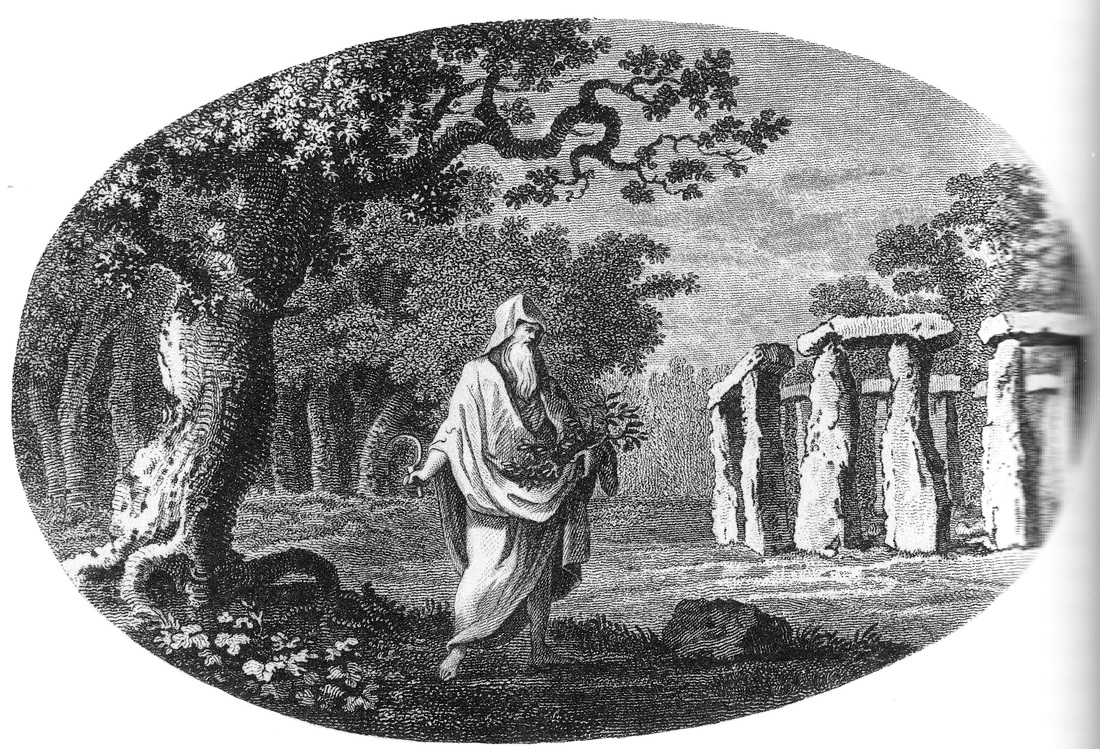

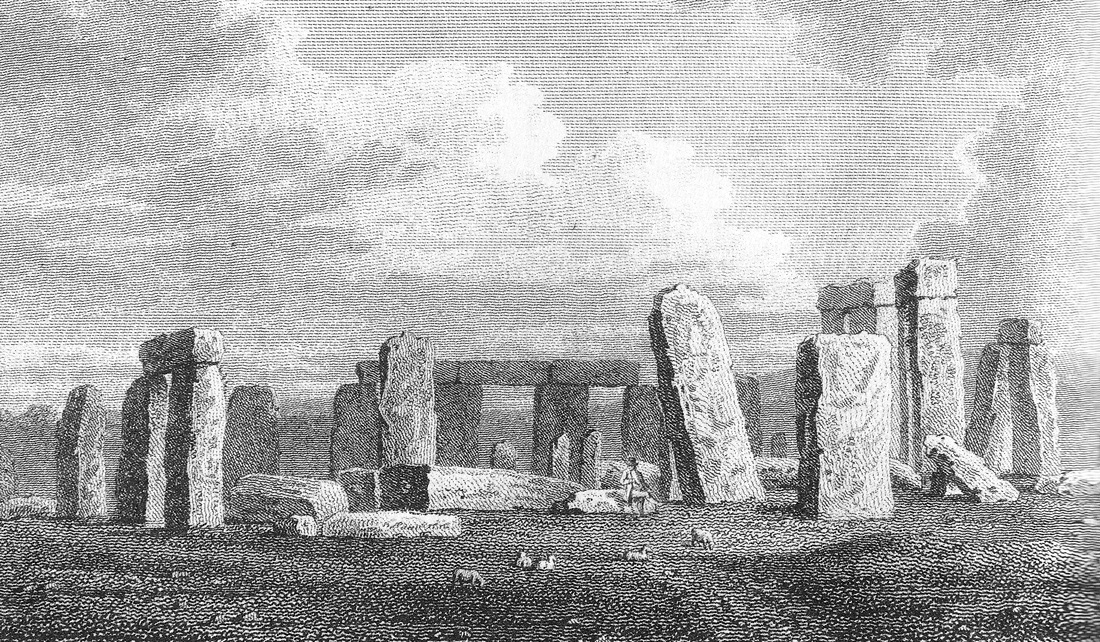

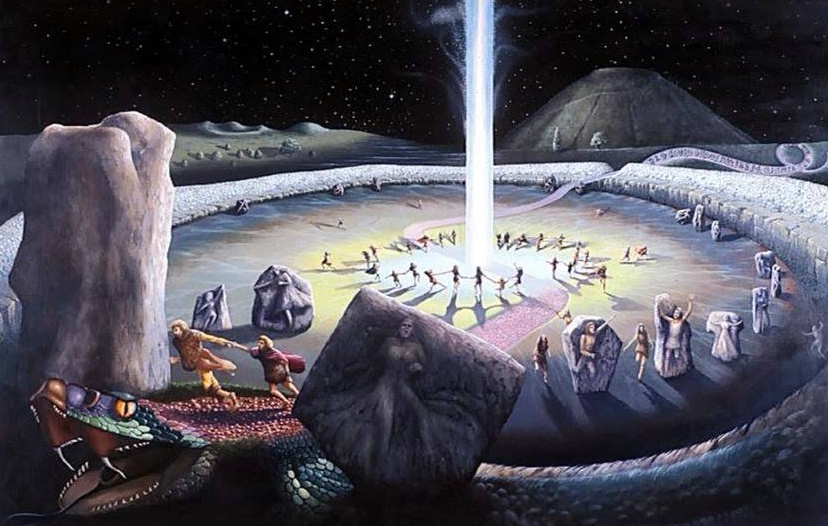

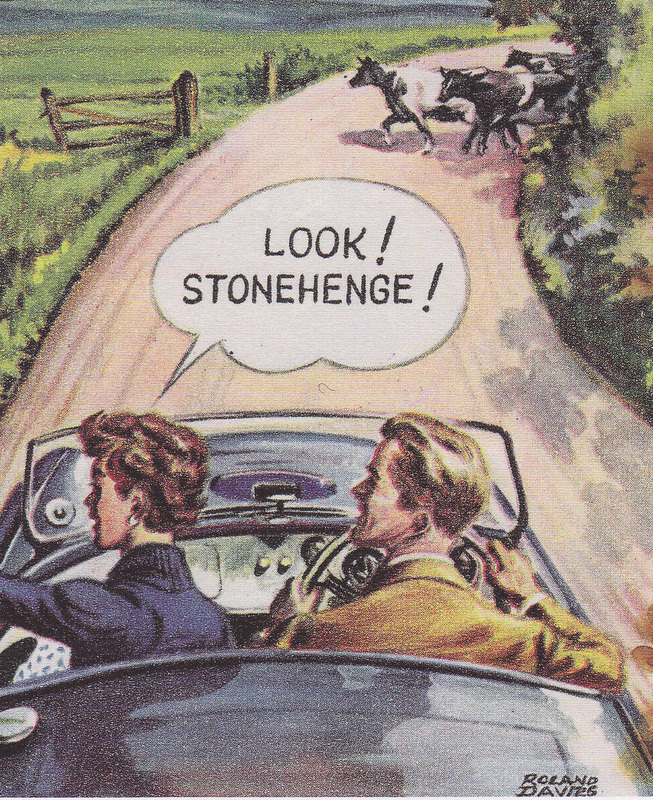

Stones of evil: Stonehenge through the ages

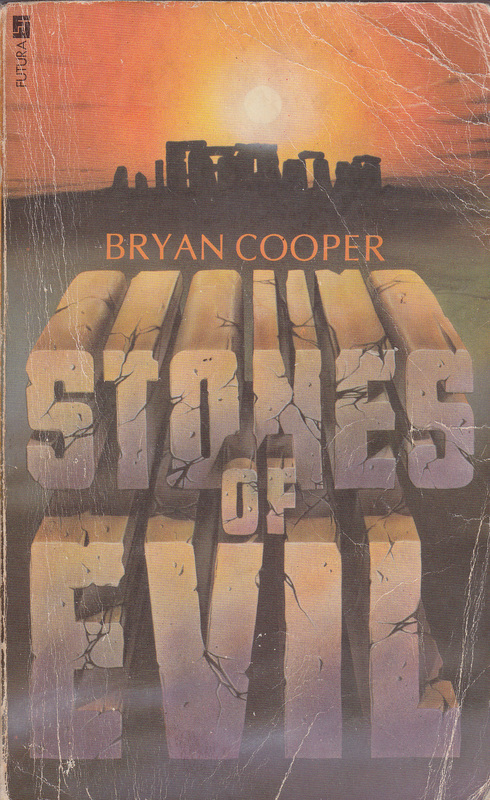

A couple of days ago I finished reading Bryan Cooper’s novel Stones of Evil (1974), which follows the experiences of a stone worker, Haril, in ancient Britain five thousand years ago. A skilled craftsman with expertise in working with flint, he finds himself among the workmen constructing Stonehenge under the direction of high priest Vardon. Initially impressed by the scale of the project and the quality of the stone, he becomes troubled at Vardon’s cruelty, especially after the priest switches his allegiance from the Sun God to the Dark One….

It’s not the sort of novel I tend to read, but I came across it in a junk shop and was intrigued by the idea of a horror tale being set in ancient Britain. Along the way, Haril meets a variety of individuals and tribes, including families from the dark ‘forest people’, groups of roaming hunters, and a religious caste that might be the precursor of the druids. The story itself provides yet another theory regarding the origins of Stonehenge, and Haril’s concluding thoughts are certainly true: ‘For the rest of time perhaps, people would come and stare silently at the ruins, wondering what had led men to build it in the first place.’

Early Birds: Du Maurier’s Precursors

West Virginian lawyer and author Melville Davisson Post (1871-1930) is perhaps best remembered now as a crime writer, and the creator of such brilliant detectives as Uncle Abner, Randolph Mason, Colonel Braxton and Sir Henry Marquis of Scotland Yard. A qualified lawyer, he had travelled in Europe and beyond, and his prolific output reflects both his wide experiences and love of the great outdoors. The Revolt of the Birds was published in New York by Appleton in 1927, three years before Post died following a fall from his horse.

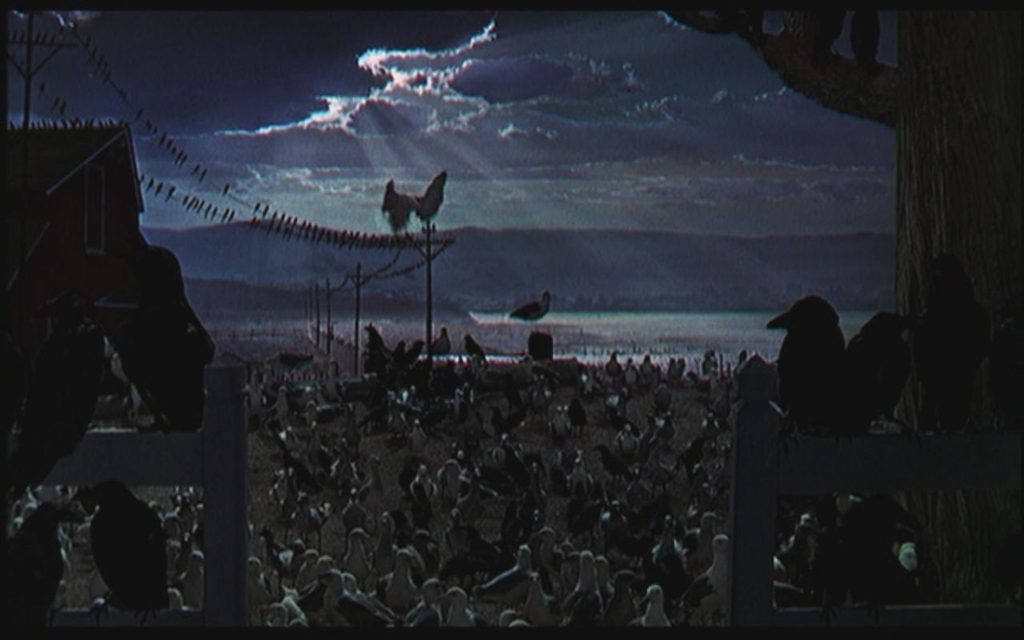

The Revolt of the Birds is set in the China Sea, and – rather like an M.R. James ghost story – is relayed through an anonymous narrator as he listens to Bennett, a seaman with the notorious Wu Fan Shipping Company. The two men are seated in a warehouse bar in Hong Kong. Bennett, an Englishman, has a copy of The Times and The Passing of Arthur which shows ‘quaint pictures of the three queens, who came in the legend, in a mystic barge to take Arthur to Avalon.’ When they start discussing whether or not such a thing could ever happen, the conversation shifts to strange happenings in the Orient and Bennett begins to tell his tale – about Arthur Hudson, his unhappy affair with an English girl, his dreams of a mysterious ‘slender, dark-haired girl’ who always appears with a flock of birds around her or beside her, and his quest to find this girl in the islands of the China Sea…. The Revolt of the Birds differs from Du Maurier’s story in one very significant point – the intention of the birds towards the humans – but it introduced the idea of a large number of birds acting together in concert against the laws of nature.

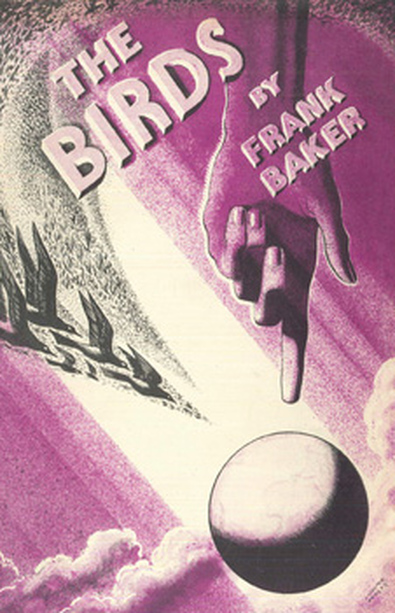

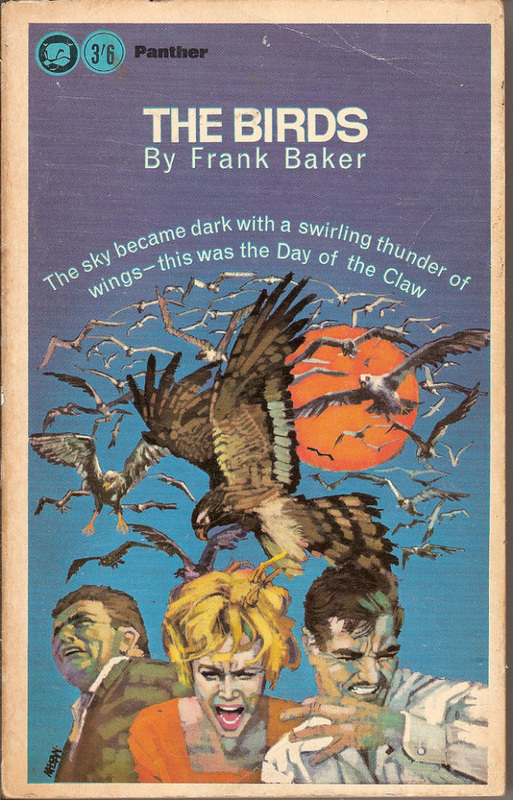

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Stories for Late at Night (New York: Random House, 1961.)Five years after Macdonald’s story, author Frank Baker (1908-82) published his full-length novel The Birds, exploring the possibility of birds carrying out a sustained war of terror against mankind.

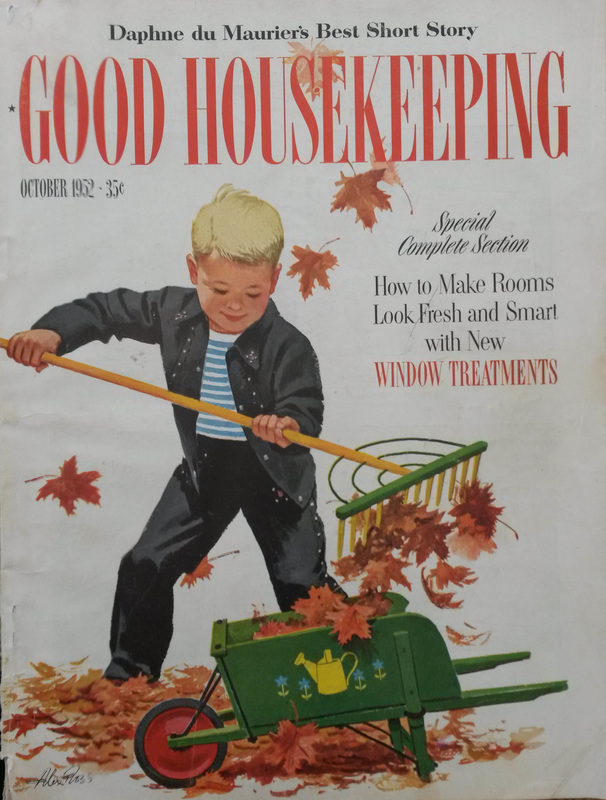

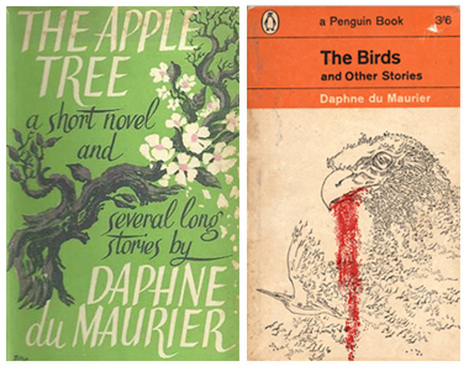

She went home and began to develop this idea, turning Tommy Dunn into Nat Hocken, and suggesting that the birds become aggressive after a harsh winter with little food. Seagulls are the first to start attacking, but they are soon joined by birds of prey and finally even small birds. The setting is clearly rural, the characters are limited to Nat’s family and neighbours, and the atmosphere is reminiscent of wartime Britain with its fears about coastal invasion and German air raids.The story was first published in Good Housekeeping magazine in October 1952, with the text broken up into fragments and printed between pages 54 and 132, interspersed with sections of other short stories and juxtaposed with dozens of housekeeping tips and adverts: “Bread stays good longer when protected with ‘Mycoban,'” “Childcraft: America’s Famous (14-volume) Child Guidance Plan” or “Jell-O Salads: Like to add a touch of glamour to dinner tonight?” This homely material seems incongruous with the grim subject matter of Du Maurier’s story, which the editors clearly regarded as potentially unpalatable – the tagline proclaimed: ‘The Editors present this, not as the most popular, but perhaps as the Most Distinguished Short Story of the Year.’

|

Baker heavily revised the text of his novel for the 1964 edition but only a fraction of these changes were implemented by Panther. A new edition was published by Valancourt Press in 2013 which incorporates all of Baker’s original revisions, and comes with a nine page introduction by Ken Mogg, who runs ‘The MacGuffin’ webpage devoted to Hitchcock scholarship. Those wishing to know more about Baker’s life should read Paul Newman’s biography, The Man Who Unleashed The Birds: Frank Baker and his Circle (Abraxas Editions, 2010.) |

Ante-Jurassic Antics: Hammer’s Prehistoric Quartet

Today sees the premiere of Jurassic World, the fourth installment of the lumbering prehistoric franchise that seems to have become a permanent fixture of weekend television. When I saw the trailer I had a sense of déja vu – not simply with regard to myself, but also for the characters: does the basic premise not ring any alarm bells with anyone visiting a theme park with live dinosaurs? Has no-one learned anything? Anyway, the trailer was so laden with CGI that I found myself hankering for prehistoric hokum from an earlier era, and have therefore been feasting on some old Hammer dvds.

The name of Hammer will always be associated with the horror genre, but the studio’s output also included science-fiction, thrillers and comedies. During a short period in its history Hammer also turned their focus on the prehistoric era, resulting in four films: One Million Years B.C. (1966), Slave Girls (1967), When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970) and Creatures the World Forgot (1971.) Compared to the contemporary Jurassic franchise, these movies might appear as antiquated as the period in which they are set, but they provide entertainment in areas that Spielberg left untouched.

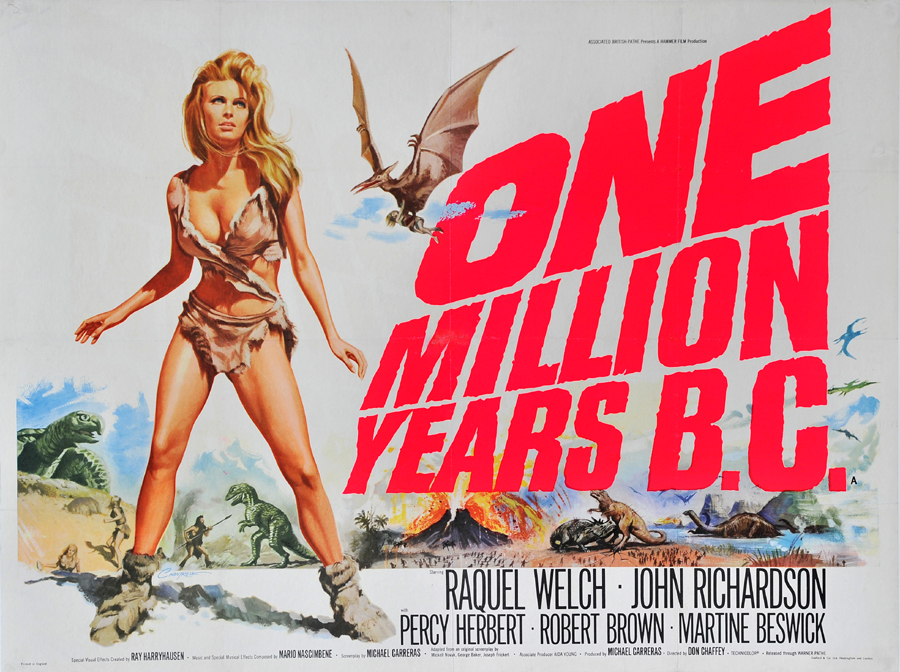

1. One Million Years B.C.

(Don Chaffey, 1966)

The movie is actually a remake of One Million B.C. (Hal Roach, 1940) which starred Victor Mature as Tumak and Carole Landis as Loana – parts played in the Hammer film by John Richardson and Raquel Welch respectively. Tumak is the son of Akkobo, chief of a dark-haired and savage tribe known as the Rock People. He is cast out from his people after a squabble over who gets to the eat the biggest chunk of meat, and after surviving a series of dangers, is rescued by the lovely Loana from the more civilised Shell People. Tumak’s rough ways are gradually softened by living with the new tribe, but the prospect of peace is threatened by skirmishes with the Rock People, dinosaur attacks and a volcanic eruption.

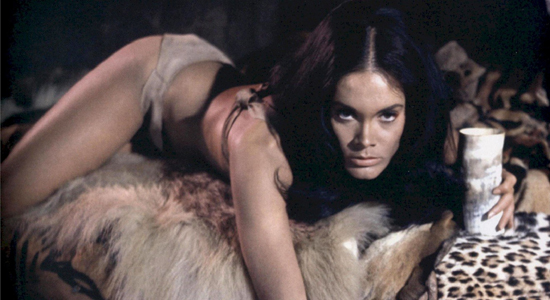

Rather than using the costly stop-motion process to depict his dinosaurs, director Hal Roach used magnified footage of live reptiles wearing stick-on fins and horns. Ludicrous although it sounds, the effects were actually so good that they were re-used in several other films such as Tarzan’s Desert Mystery (Wilhelm Thiele, 1943), Two Lost Worlds (Norman Dawn, 1951) and Valley of the Dragons (Edward Bernds, 1961.) The most iconic image from the film is, of course, that of Racquel Welch in her fur bikini; it would be a dreadful sin of omission if I failed to include a picture.

The 1966 movie sticks fairly closely to the story of the original, but for the dinosaur scenes they turned to Ray Harryhausen, whose stop-motion animation technique has recently been used in Jason and the Argonauts (Don Chaffey, 1963) and First Men on the Moon (Nathan Juran, 1964.) Some live action sequences – involving a magnified iguana and tarantula – were also included as a nod of respect towards Hal Roach’s movie.

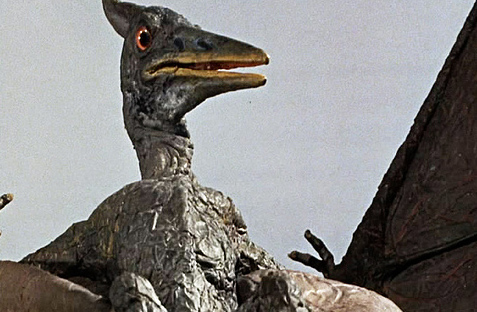

Highlights include a battle between a tyrannosaurus rex and a triceratops, an attack on the settlement by an allosaurus, where a young girl is stranded up a tree, Loana being carried away by a pterosaur or flying lizard (below.)

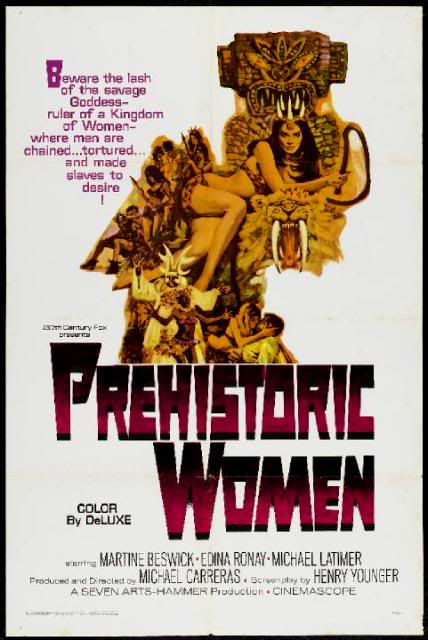

2. Slave Girls/ [In U.S. – Prehistoric Women]

(Michael Carreras, 1967)

As executive producer of Hammer Films from 1955, Michael Carreras was the driving spirit behind much of the studio’s output over the next two decades and was the producer of all four films featured here. Slave Girls (released in America as Prehistoric Women) is, however, the most ridiculous of the quartet, and studio executives were well aware that it was a sub-standard effort. It was shot in four weeks, re-using sets and costumes left over from One Million Years B.C. – a cost-cutting tactic frequently used by Roger Corman for his B-movies.

The script is far-fetched, to say the least. Big-game hunter David Marchand (Michael Latimer), has been captured by African tribesmen and is about to be sacrificed when a time portal opens up and transports him back to a prehistoric world populated by two tribes of women – one blonde, the other brunette. The latter are the dominant tribe, headed by Queen Kari (Martine Beswick), and the poor blondes – who happen to be rhino-worshippers – live in a state of slavery, while the men are imprisoned in a dungeon. Marchand’s arrival makes things worse, especially when he falls for blonde slave girl Saria (Edina Ronay). Whether these are prehistoric slave girls or merely women in a jungle somewhere is never resolved, and there is even a hint that the entire episode may have been some sort of dream after Marchand passes out.

Despite the absurdity of all this, Martine Beswick delivers an impressive performance as the imperious Queen Kari. A less dignified scene sees her recreating her catfight with Raquel Welch in One Million Years B.C., this time with Carol White, whom sharp-eyed viewers might remember as the young Sibella in Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949) – she was soon to receive great acclaim in the role of a homeless single mother in Cathy Come Home (Ken Loach, 1966.) Beswick went on to appear in From Russia with Love and Thunderball, but her Bond girl roles were really a step down from Queen Kari.

In many UK cinemas Slave Girls was screened as a double bill with The Devil Rides Out (Terence Fisher, 1968)

3. When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (Val Guest, 1970)

The movie is underpinned once again by rivalry between blondes and brunettes. A dark-haired tribe are about to sacrifice a group of blonde victims as an offering to protect them from dinosaur attacks, when a freak storm (apparently to do with the creation of the moon) disrupts the ceremony. One of the blonde women, Sanna (Victoria Vetri) escapes by plunging off the cliff into the sea, from which she is rescued by members of another tribe – including Tara (Robin Hawdon), whose affection for her rouses the jealousy of his ‘wife’ Ayak (Imogen Hassall.)

The hostility of Ayak is just one of the difficulties faced by Sanna – she has to fend off dinosaur attacks, escape from giant snakes and carnivorous plants, while the priest (Patrick Allen) from whom she escaped at the start comes looking for her and manages to convince her rescuers that she is responsible for their misfortunes. Everything comes to a head on a beach, just as a tsunami prepares to roll in – one of many scenes in which the laws of nature appear to have been suspended.

The film follows the same structure as One Million Years BC, and the caveman ‘language’ is used much more extensively – which does become tedious rather quickly. There is some effective handheld camera work and intriguing scenes, such as one where we see one of the Beach Tribe women applying tar to young girl’s blonde hair.

Highlights include a beach attack by a plesiosaur, a battle with a triceratops-like chasmosaurus , a delightful baby dinosaur and its less delightful mother, and another flying lizard snatch.

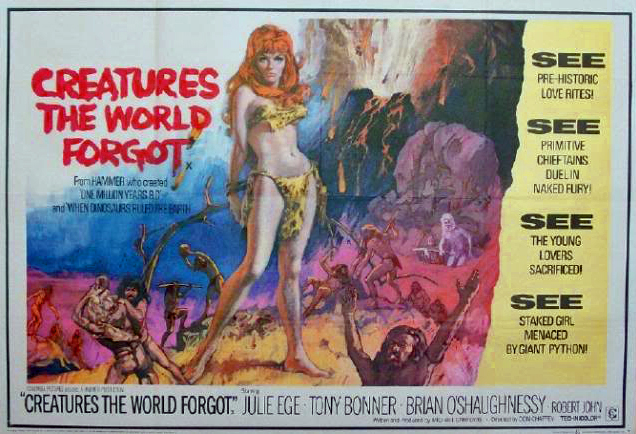

4. Creatures the World Forgot

(Don Chaffey, 1971)

The title is slightly misleading, as the reference to creatures raises some expectation of more dinosaurs, but alas, the movie is devoid of prehistoric monsters and instead provides another tale of rivalry between dark-haired and fair-haired tribes. This conflict is personalised when a woman gives birth to twin sons, one blond (Toomak) and the other dark-haired (Rool); recalling Biblical tales of Cain and Abel or Jacob and Esau, the two grow up as rivals, the situation exacerbated when Toomak is given the hand of Nala (Julia Ege), daughter of a tribal chief. We do get to see a sabre-toothed tiger and a python, but despite the presence of former Miss Norway, Julia Ege, the film is more concerned with cavemen rather than women, whose dialogue consists of grunts that are even less eloquent than the prehistoric ‘dialect’ used in the previous film. It may be just as far-fetched as the films outlined above, but there is a sense with Creatures the World Forgot that Hammer was making a stab at realism: the world depicted here is certainly a more plausible than one in which dinosaurs and humans romp about together. There are some interesting depictions of folklore rituals involving masks and talismans, and the film makes the most of the location shots in Namibia, incorporating footage of native wildlife.

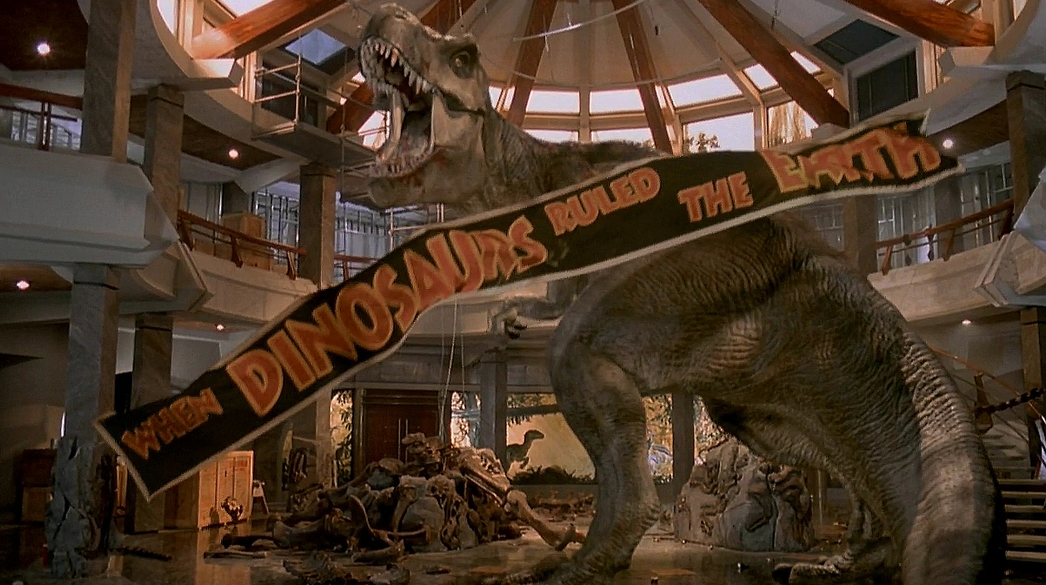

The influence of these films is discernible upon subsequent prehistoric romps such as The Land That Time Forgot (Kevin Connor, 1975) its sequel The People That Time Forgot (Kevin Connor, 1977) and the totally anachronistic nonsense of 10,000 BC (Roland Emmerich, 2008) whose time-specific title must surely be a respectful nod towards the earlier Hal Roach/Hammer movies. Although they have managed to move away from the sexist and racist overtones of the Hammer era, the Jurassic Park franchise continues to indulge audiences’ desire to see humans and dinosaurs on screen together, and they even make a direct allusion to the earlier movies: