During my last visit to Vienna I spent some time in a second hand shop near the Sigmund Freud Museum, and while browsing there came across a set of the collected works of Gottfried Keller. It was a lovely little set of small octavo volumes, in decorated green cloth bindings, and I was sorely tempted when I saw that the story ‘Regine’ was included. After some internal arguments, however, I had to put the books back – I was flying with hand luggage only and my bag was already bursting with books. As consolation, I found a copy of Alfred Ibach’s biography of Paula Wessely – Die Wessely: skizze ihres Werdens (1943), which I picked up for only 1 Euro. I will write about Wessely below, but first I am going to turn to the two actresses who co-starred with AW in Regine: Luise Ullrich and Olga Tschechowa.

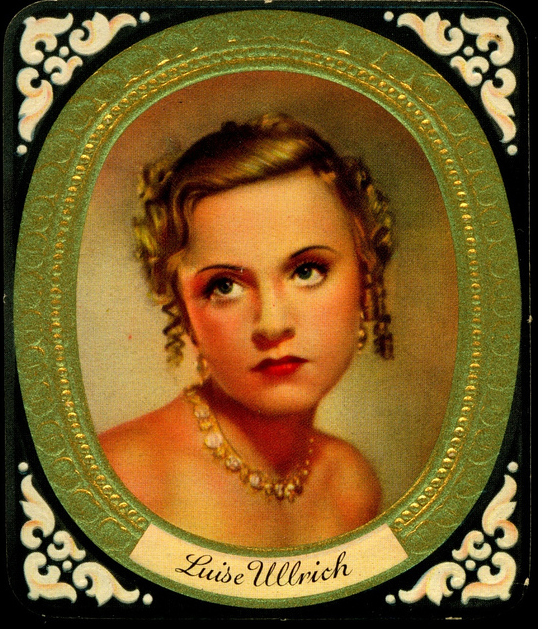

Luise Ullrich (1910-85)

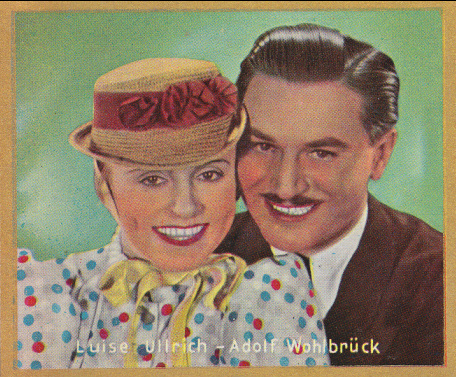

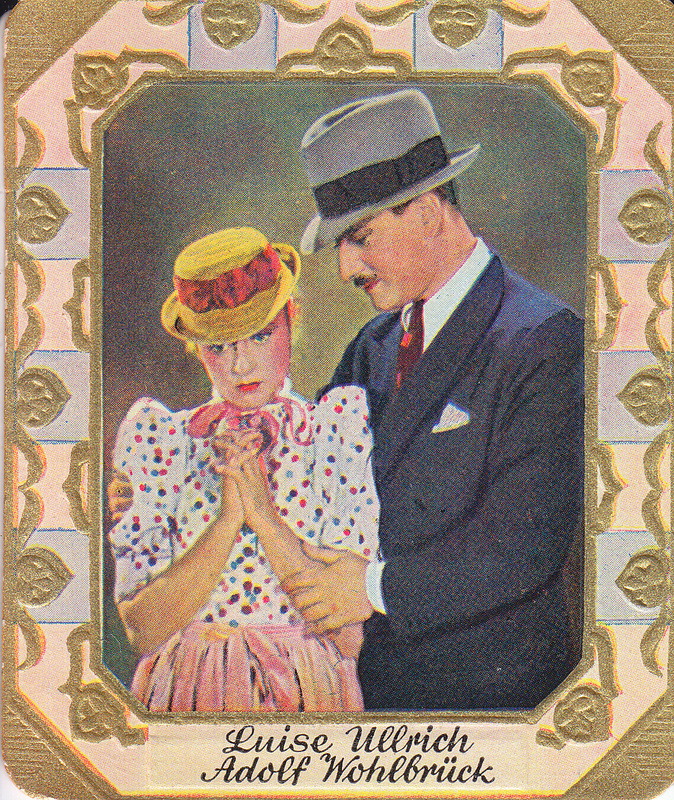

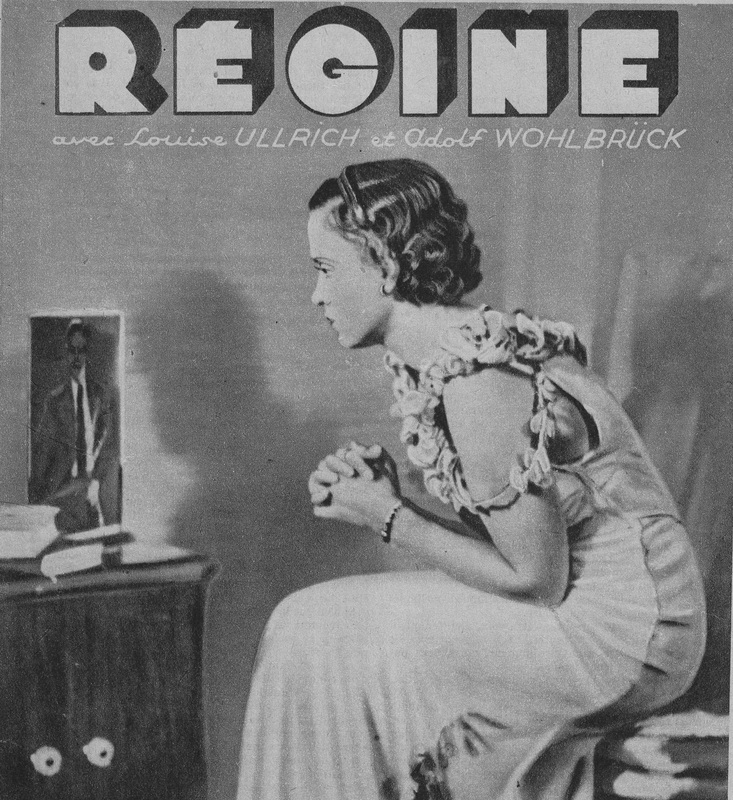

Starred with AW in Regine (1935)

The film Regine is based upon a novella written by Swiss-German author Gottfried Keller, and published in his story-cycle Das Sinngedicht (The Epigram) in 1881. The movie is more sentimental than the novella and makes a number of changes, but the story of an eminent engineer who falls in love with a lowly maid is essentially the same.Luise Ullrich had a fresh-faced innocent beauty that made her ideally suited for the role of Regine. Born in Vienna on 31 October 1911 to a count and major in the Austro-Hungarian army, she studied at the Academy of Music and Performing arts in Vienna before making her stage debut in the city in 1926. After some five years she moved to Berlin, where she was spotted on stage at the Lessing Theater by actor-director Luis Trenker, who cast her opposite himself in the film Der Rebell (1932) about a Tyrolean hero fighting Napoleon’s forces. Her real breakthrough came the following year, however, when she appeared opposite Olga Tschechowa in Liebelei (1933), directed by Max Ophuls.

In this film, based on a story by Arthur Schnitzler, she played the part of Mizzi who, with her friend Christine (Magda Schneider), makes the acquaintance of two cavalry officers Lobheimer (Wolfgang Liebeneiner) and Kaiser (Willi Eichberger, whom AW encouraged to go to Hollywood where he changed his name to Carl Esmond.) They meet at a concert in Vienna when the mischievous Mizzi drops her opera glasses from the balcony onto the officers below. While Mizzi pairs off with Kaiser, Lobheimer falls for Christine, having already decided to break off his affair with Baroness Eggerdorff (Tschechowa.) Unfortunately, Baron Eggersdorff (Gustaf Grundgens) has discovered his wife’s adultery, and events take a tragic turn….

The film displays some beautiful cinematography by Franz Planer, who would make similar use of his talents filming AW and Tschechowa in Maskerade. Both films are brilliant evocations of the mythical ‘old Vienna’ to which Ophuls returned with La Ronde (1950), again adapted from a Schnitzler play but this time with AW centre-stage. Liebelei shares some similarities with Maskerade, such as the lush background of Viennese music plus the themes of aristocratic adultery and the etiquette of dishonour. Its success brought Ullrich further lead roles, including that of Regine.

Regine tells the story of Frank, an engineer returning to his native Germany for the first time in ten years after working in America. On the ship home he meets actress Floris Bell (Olga Tschechowa), whose advances he rejects. As Frank has no family, he goes to stay at his uncle’s house in southern Germany (there are wonderful location shots filmed in Bavaria and the Rhineland), where he falls in love with – and marries – his uncle’s housemaid, the humble Regine.

Regine’s social awkwardness creates some scenes that are alternately comical and touching. Inevitably, there is tension and difficulties, and a misunderstanding – caused in part by Floris – leads Frank to suspect Regine of seeing another man while he is away. Distraught, Regine tries to take her own life…but in a film like this, matters are – of course – resolved happily.

Regine was released in Germany a few weeks before Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will – a fact that demonstrates the diversity of films available to cinema goers under the Nazis. Furthermore, it was Regine, rather than any overt propaganda, which Germany submitted as its entry to the Venice Film Festival that year. Clearly, it was held in high regard.

Olga Tschechowa (1897-1980)

Starred with AW in Maskerade (1934) and Regine (1935)

This silent who-dunnit is set in a castle where a group of aristocratic guests await the arrival of Baroness Safferstätt (Tschechowa, above). In the meantime, an uninvited and unwelcome guest arrives – Count Oetsch (Lotar Mehnert), whom everyone believes murdered the baroness’s first husband, his brother Peter (Paul Hartmann). Tension rises after the baroness arrives with her second husband (Paul Bildt), accusations are made, and the pious friar Father Faramünd mysteriously disappears from a locked room….

Although the film is a pale shadow of Murnau’s later work, Tschechowa gives a mesmerising performance as the Baroness, and further work quickly came her way. She made around forty silent films before migrating to talkies with Die Drei von der Tankstelle (1930), a hugely popular musical comedy that inspired several imitations, including Drei von der Stempelstelle (1932) starring AW. The success of the film encouraged Tschechowa to sail to Hollywood later that year. Although she partied with Garbo, Fairbanks, Lloyd and Chaplin, her Hollywood career was short-lived as American audiences found her Russo-German accent too thick. She returned to Germany and continued making films.

Love triangle: with AW in ‘Maskerade’, next to a painting of Leopoldine Dur (Paula Wessely) on the easel

Love triangle: with AW in ‘Maskerade’, next to a painting of Leopoldine Dur (Paula Wessely) on the easel

She moved in high circles during the 1930s and two years after Maskerade was awarded the status of Staatsschauspielerin. However, at the same time as this ‘State Actress of the Third Reich’ was wining and dining with Goebbels and Hitler, she was passing information about them to Soviet officials. Although there is no doubt that she was working as a Russian agent during the war, there is no indication that she contributed much of value. The Russians appreciated having a contact who enjoyed access to the private company of Hitler and Goebbels; there were also plans for her brother Lev Knipper to assassinate the Führer if she could get him close enough. After the war Tschechowa was rewarded for her work with financial support and an apartment in the Russian sector of Berlin.

Olga and Lev were very fortunate to survive throughout this period, but her ability to flit effortlessly between regimes – Tsarist, Bolshevik, Nazi and Stalinist – suggests that her allegiance remained primarily to herself rather than to the world around her. Tschechowa’s clandestine activities and unreliable memoirs make it hard to gain any real sense of her personality. She moved to Munich in 1950, launched a range of cosmetics and gradually retired from acting, although her daughter Ada (1916-66) and grand-daughter Vera (1940-) both became successful actresses and Olga herself made something of a comeback in the 1970s. She died in Munich on 9 March 1980, sipping champagne and murmuring ‘Life is beautiful.’

Paula Wessely (1907-2000)

Starred with AW in Maskerade (1934.)

Like so many of AW’s comedies of this period, Maskerade revolves around a misunderstanding over identities. The painter Heideneck (AW) has a reputation as a womaniser but has broken off with his former lover Anita Keller (Tschechowa) now that she is engaged to music director Paul Harrandt (Walter Janssen). Her fiance’s brother, surgeon Dr Carl Harrandt (Peter Petersen), is married to Gerda (Hilde von Stolz), who slips away from the carnival celebrations to be painted wearing only a mask and a chinchilla muff that she has borrowed from Anita.