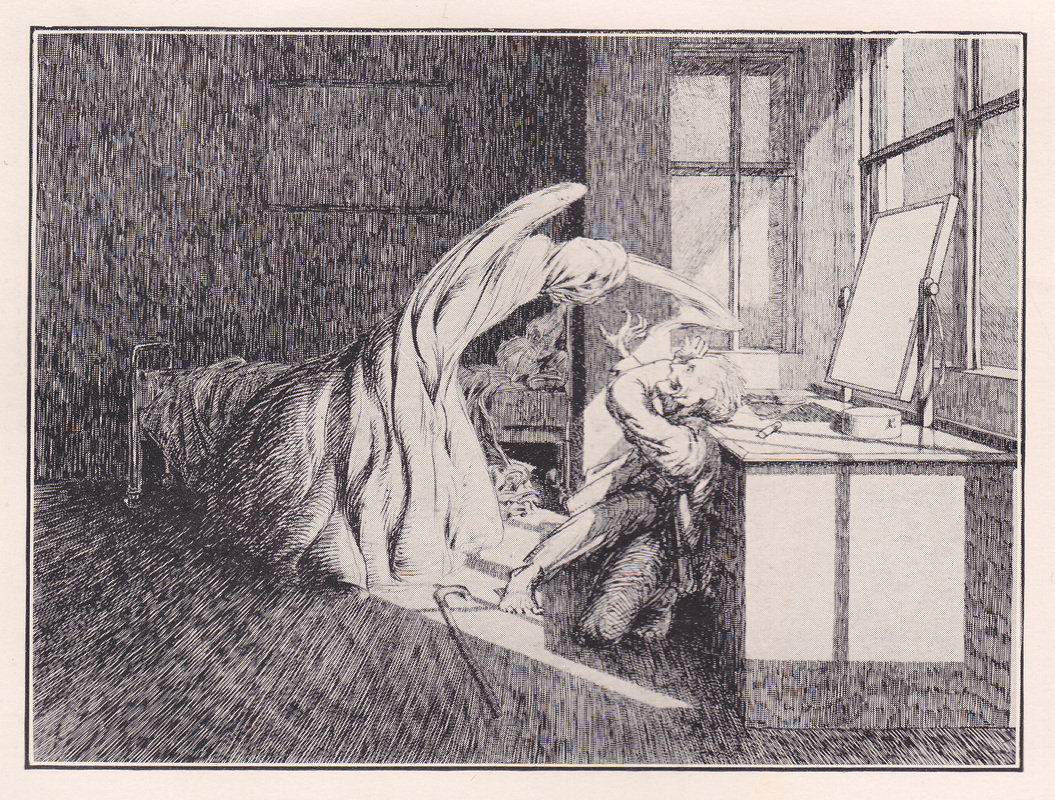

The effectiveness of M.R. James’ghost stories owes much to the author’s ability to create sensations of physical unease in the reader, particularly through the sense of touch. He never relies on merely visual effects, such as the sight of a grisly spectre or the shock of recognising a dead ancestor. Many of his stories were, of course, written in order to be read aloud rather on the printed page. One might therefore question the purpose of illustrations for his stories; can they enhance the reading experience, or might they prevent the text from guiding the reader’s imagination in the way that James intended?

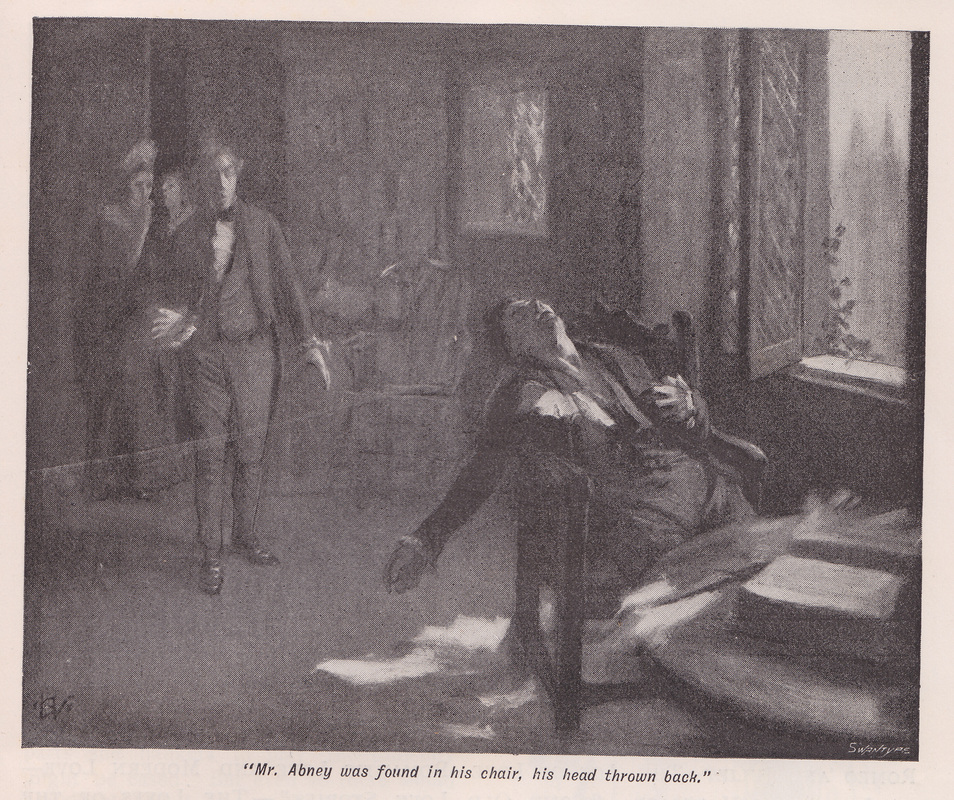

Whatever the reader might feel, illustrations were seen as desirable by most publishers during the period in which Monty was writing, particularly for popular periodicals. In this blogpost I’m going to look at some of the illustrations that accompanied his earlier works, beginning with ‘Lost Hearts’ which appeared in the December 1895 issue of Pall Mall magazine.

The artist commissioned to illustrate James’ story was Simon Harmon Vedder (1866-1937), a young American artist whose reputation was on the rise following recent exhibitions at the Paris Salon. Vedder went to provide illustrations for authors such as Elizabeth von Arnim, G.A. Henty, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Sir Walter Scott, but his watercolour style does not indicate a strong sympathy with the tone of ‘Lost Hearts’ and the pairing is not entirely successful.

Both ‘Lost Hearts’ and ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrapbook’ were read by James at the 601st meeting of the Chitchat Society at Cambridge on 28 October 1893, just around the time that a young artist named James McBryde came up to the university from Shrewsbury.

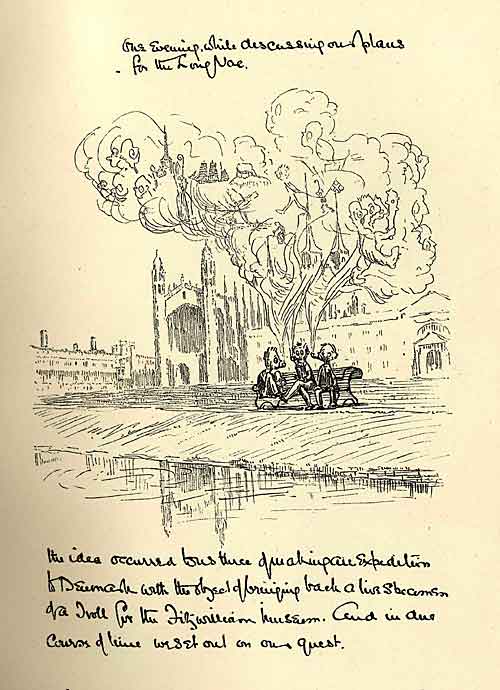

Despite their different backgrounds, the two men became close friends, cycling along the Danube together in September 1895, travelling through Denmark and Sweden in the summers of 1899, 1900 and 1901 – these Scandinavian trips inspired the stories ‘Number 13’ and ‘Count Magnus’ – as well as visiting Aldeburgh together in 1902.

McBryde had originally intended to follow a medical career, but after completing his training at St Bartholomew’s in 1902 he decided to pursue a career in art instead, and began studying at the Slade School of Art in the autumn. Despite his marriage to Gwendolen Grotrian the following summer, and the fact that he lived in London while James remained in Cambridge, the two men remained close friends. The idea of combining McBryde’s artwork with Monty’s stories seems to have originated with L.F. Giblin, a friend of the artist who had also entered King’s at the same time. When McBryde fell ill with appendix trouble in March 1904, the project seemed an ideal way to distract him during his convalescence.

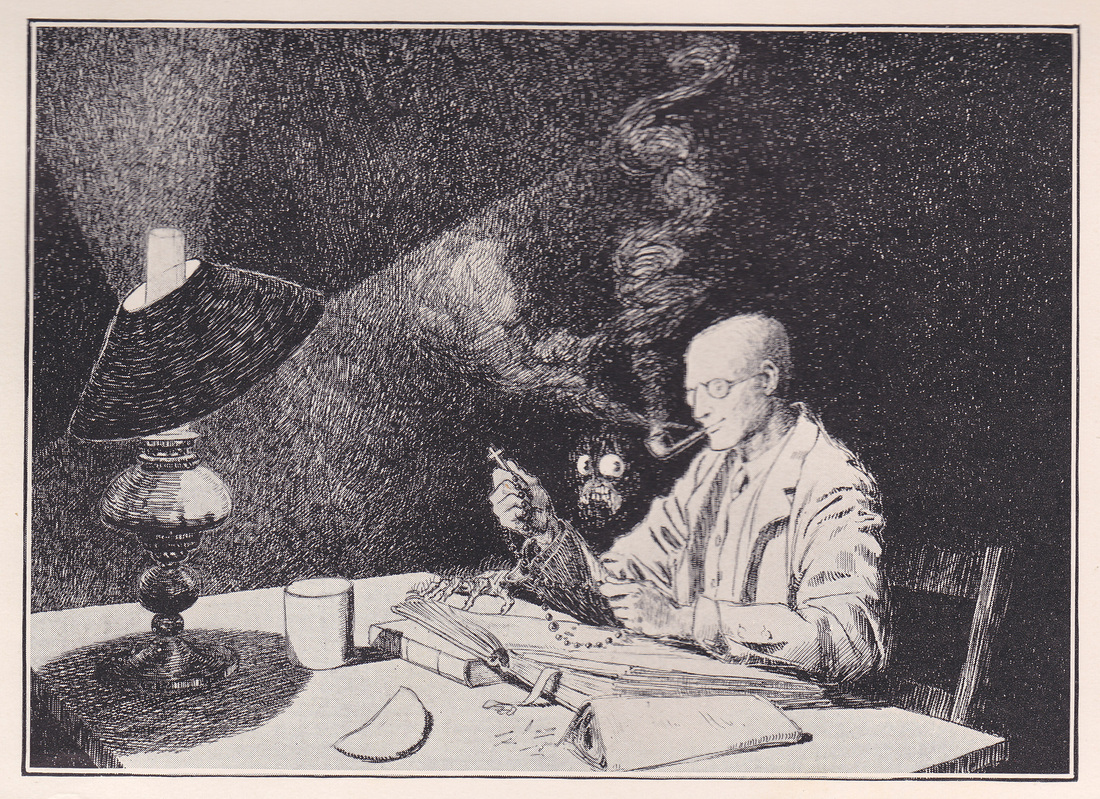

Monty responded positively to the suggestion, and six of his supernatural tales were chosen for the anthology – ‘Canon Alberic’, ‘The Mezzotint’, ‘The Ash Tree’, ‘Number 13’, ‘Count Magnus’ and ‘Oh Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad.’

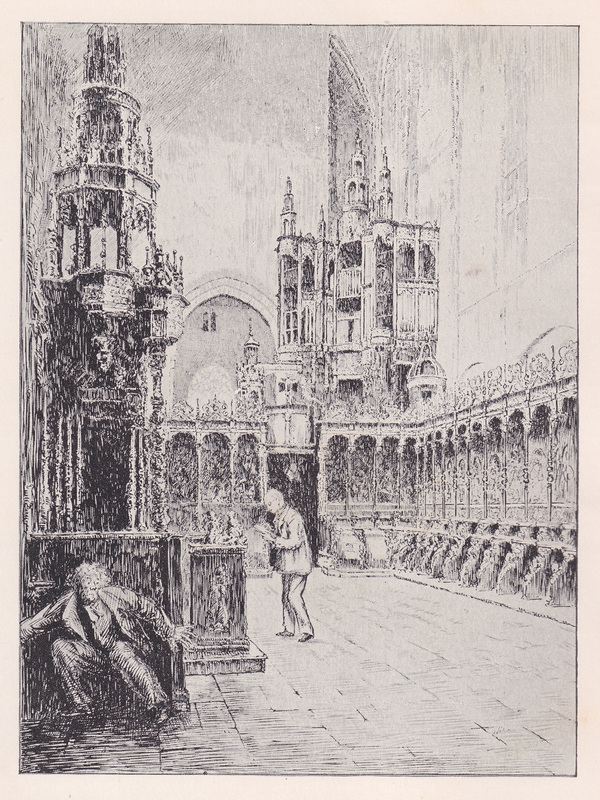

The drawing below is an illustration for ‘Canon Alberic’ and was used as the frontispiece for the collection. It was based on a photograph of the interior of St Bertrand de Comminges, which M.R. James had visited in April 1892.

Sadly, these were to be his last drawings. On 31 May McBryde underwent surgery on his appendix, and despite early signs that all had gone well, he died at 9.30 am on the 5th June. His widow Gwen, who was then expecting their first child, returned the drawings to Monty. Despite his publisher’s recommendation that another artist be found to complete McBryde’s work – Arnold recommended H.J. Ford – Monty insisted that the collection be published with just the four drawings as a tribute to his friend. In the meantime he wrote to Gwen and offered to publish The Story of a Troll Hunt, which McBryde had written and illustrated following their trip to Denmark in 1899. Gwen agreed, and the volume was published by Cambridge University Press with a preface by Monty.

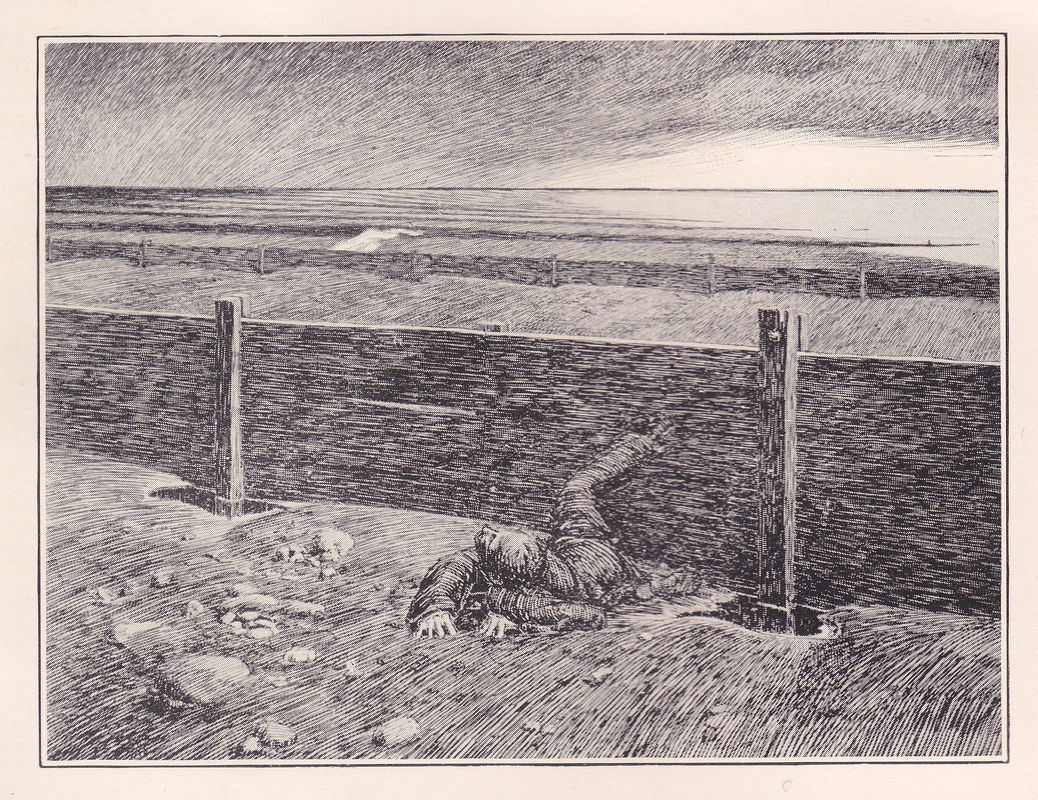

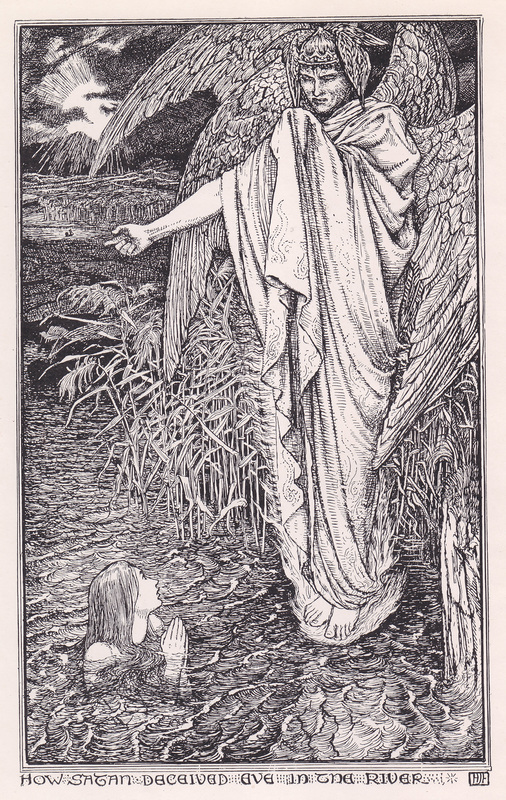

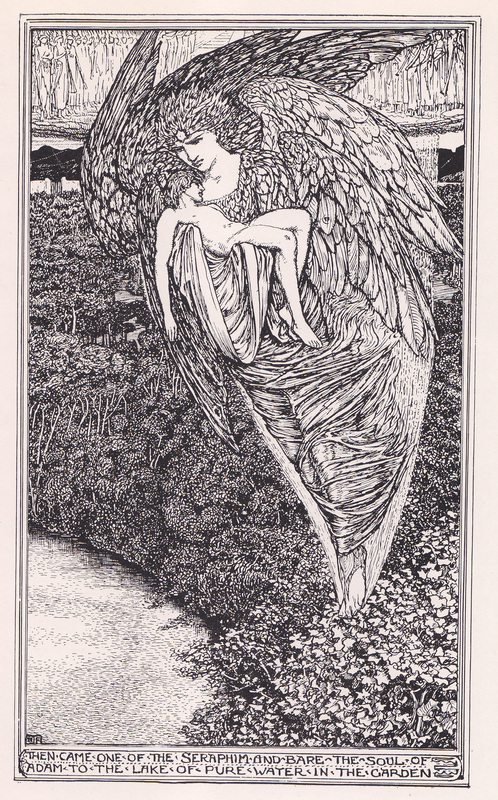

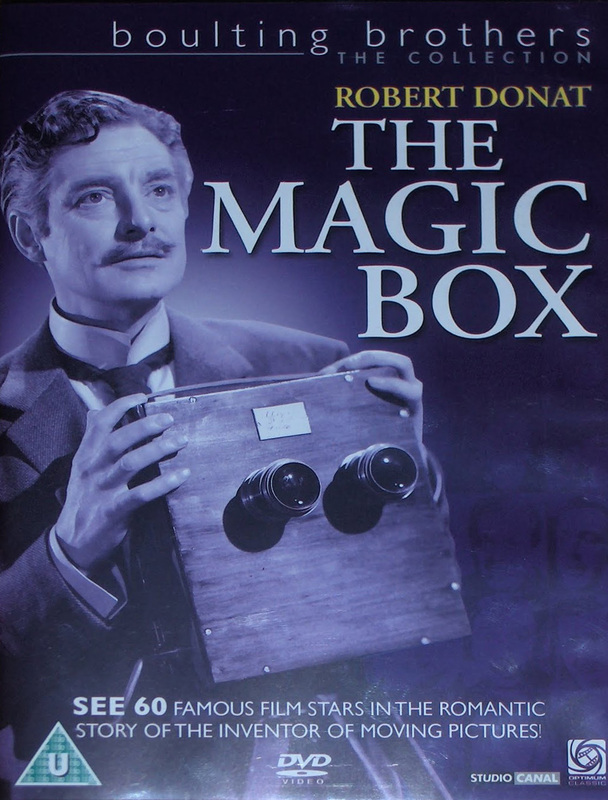

As mentioned above, publisher Edward Arnold had originally suggested that Ghost Stories of an Antiquary be illustrated by Henry Justice Ford (1860-1941.) Monty’s refusal of this had nothing to with Ford’s qualities as an artist, and within a few years he was again invited to illustrate a book by M.R. James.

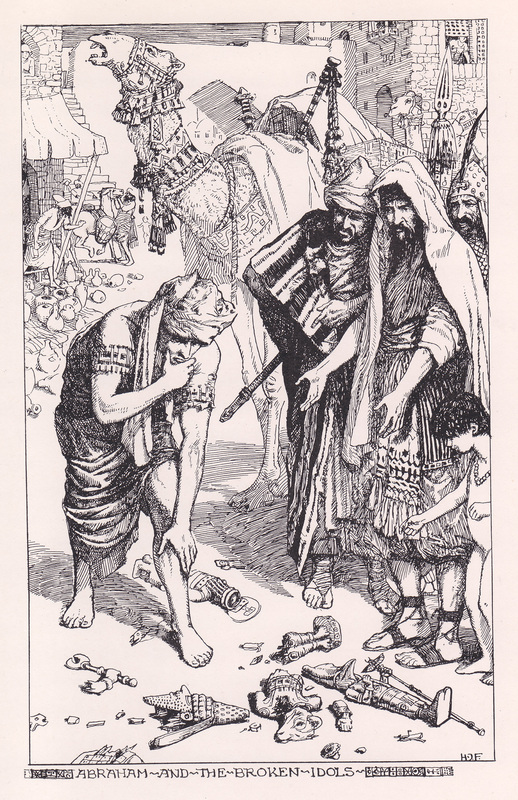

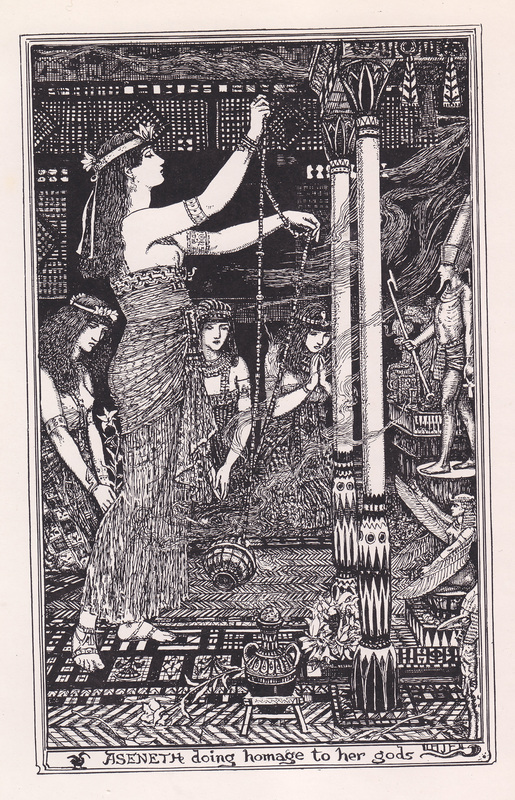

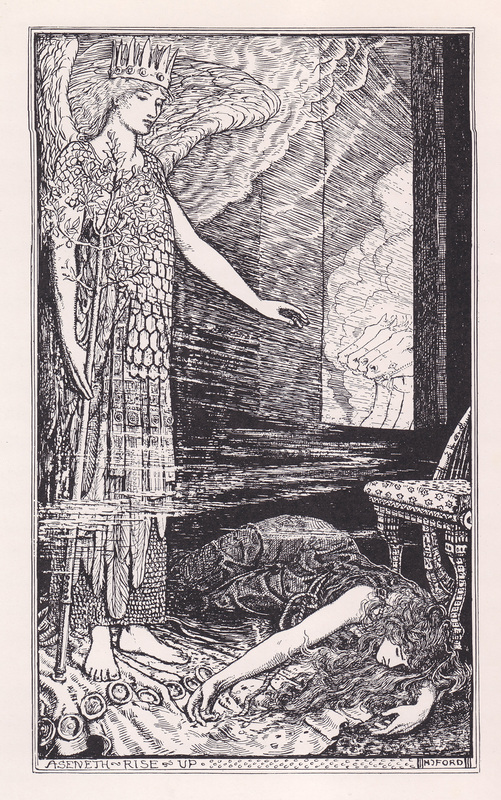

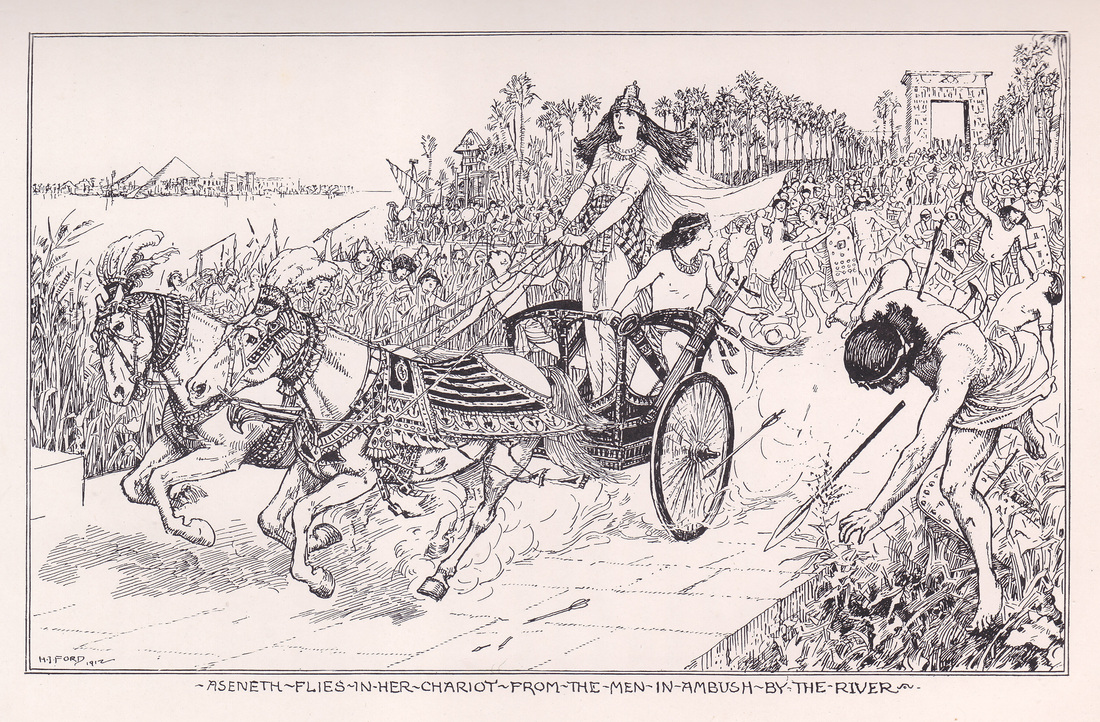

Old Testament Legends; being stories out of some of the less-known apocryphal books of the Old Testament (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1913) is a collection of eight tales adapted by James for children, drawn from stories in the non-canonical Biblical literature known as the ‘Apocrypha’. James had a profound knowledge of the subject – he had edited a collection of Apocrypha Anecdota for Cambridge University Press in 1893 and would later write The Lost Apocrypha of the Old Testament: their Titles and Fragments Collected, Translated and Discussed (London: SPCK, 1920) while his Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924) remained for several decades the standard reference work for Scripture scholars. Prefaced with a clear explanation of the subject for younger readers, the collection includes the following stories:

1. Adam

2. The Death of Adam and Eve

3. Abraham

4. The Story of Aseneth, Joseph’s Wife

5. Job

6. Solomon and the Demons

7. The Story of Ebedmelech the Ethiopian and of the Death of Jeremiah

8. Ahikar

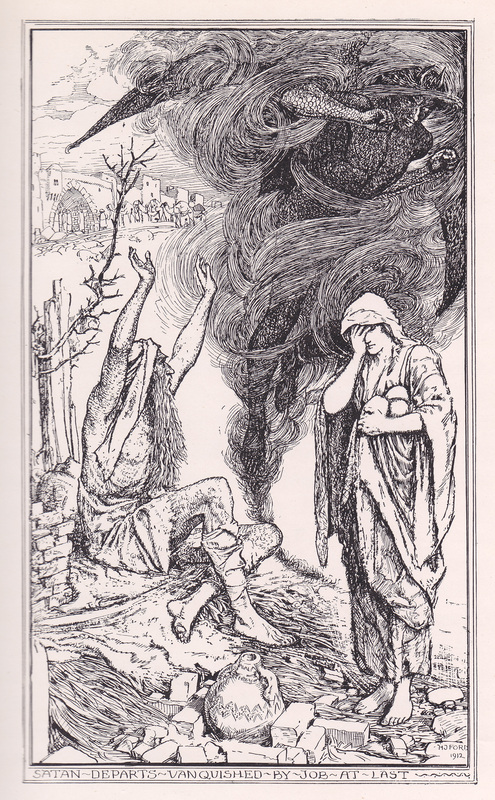

Ford’s bold black and white drawings accompanied all the stories except No.7, and there were no less than three illustrations for the legend of Aseneth. This uneven distribution suggests to me that Ford submitted a portfolio of pictures, from which the editor may have struggled to make a selection. It seems unlikely that the quality of the illustrations was uneven, given Ford’s evident skill as a draughtsman, so if there were any shortcomings these were probably to do with his treatment of the subjects. The style of the illustrations fits well with the text. There is none of McBryde’s whimsy here, as readers would expect Biblical topics (even from the Apocrypha) to be handled with respect. Nor is there anything resembling the sentimental pastel tones of Vedder. Some of the drawings are in fact remarkably powerful.