This was the first horror film in which Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee appeared together, and the pair would co-star in around twenty others, many of them Hammer productions. For copyright reasons Hammer needed to distinguish their imagery from James Whale’s 1931 classic, and make-up artist Phil Leakey made Christopher Lee look very different from Boris Karloff’s creature. The contrast is more than skin deep, however – Lee plays the creature as a brain-damaged monster, with little apparent capacity for thought or emotion; it is hard for modern audiences to feel much sympathy for him, especially given the creature’s lack of screen time. The physicality of Lee’s performance is astonishing nonetheless; jerking, flailing and lurching, he captures the tragedy of a being unable to controls its own limbs.

The real monster of the film is Victor Frankenstein, who is prepared to sacrifice everything – ethics, friendship, his fiancee, mistress and unborn child – for science. Peter Cushing’s performance is impeccable; the subtlety of his facial expressions seemed much more impressive on the big screen. He returned in this role for another four films, all directed by Terence Fisher: The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Frankenstein must be Destroyed (1969) and Frankenstein and The Monster from Hell (1974.) In 1958 he played Von Helsing opposite Lee’s Count Dracula, and the two of them would continue to reprise these roles – with constant variations – over the next two decades. Hammer Film Production’s reputation as purveyors of luridly-coloured Gothic gore began with The Curse of Frankenstein and the film contains motifs that would recur again and again in the studio’s output.

Another highlight of the film was the lovely – if rather underused – Hazel Court, playing the part of Frankenstein’s fiancee Elizabeth. She gets to wear a series of ravishing costumes in the film, of which the gown below is probably the finest. Not ideal for grubbing around a dungeon full of chemicals, but certainly a feast for the eyes. Hazel was a classically trained actress and had done several films before The Curse of Frankenstein – hence my regret that her character is so under-developed. Elizabeth is a typical heroine-victim in the Gothic tradition, entering a house of horror (both building and family lineage, as in the House of Usher) through marriage, and thereby trespassing upon dark secrets that threaten to engulf her. A comment by Paul Krempe indicates that Frankenstein had forbidden Elizabeth to look behind his laboratory door – a prohibition that recalls the legend of Bluebeard’s Castle – but of course she does…

Certain elements of the plot are reminiscent of other Gothic narratives, and there is a parallel with Gaslight in the baron’s flirting with the maid behind his fiancee’s back. He is ultimately punished for his immoral behaviour and the innocent Elizabeth finds refuge with Frankenstein’s friend and former tutor Paul Krempe, who is often regarded as the film’s moral compass. Despite his sanctimonious pontificating, however, his conduct seems to me as murky as the baron’s. He knows that Frankenstein’s experiments are unethical and repeatedly warns that their work ‘can only end in evil’, yet he keeps returning to help and evidently cannot resist his fascination with Frankenstein’s project. As his mind has not been corrupted to the extent that Victor’s has, Krempe arguably has more capacity to end the wickedness, and so his failure to act makes him even more culpable. His final silence not only conceals his part in the baron’s work, but also offers a neat way to remove Elizabeth’s fiance from the scene when it is obvious that he wanted her for himself all along. Just as Frankenstein got rid of his former lover when she began to get in the way, so too does Krempe callously dispose of his friend, using the executioner in much the same way that Frankenstein used the creature. (Although if the 1958 sequel The Revenge of Frankenstein is to be believed, the baron evades the guillotine and returns to his work.)

There is always the temptation, of course, to read more into these old films than their makers ever intended. Screenwriter Jimmy Sangster has been frank about the extent to which his work was driven by purely commercial concerns, admitting his bewilderment when Hammer fans ask him about Freudian symbolism, literary echoes and other esoteric nuances that they detect. That is not to say that such motifs are actually absent. Fisher may have wished to create a definite distance between The Curse of Frankenstein and Universal’s 1931 movie, but his film – consciously or unconsciously – contains clear homages to classic horror tradition, e.g.

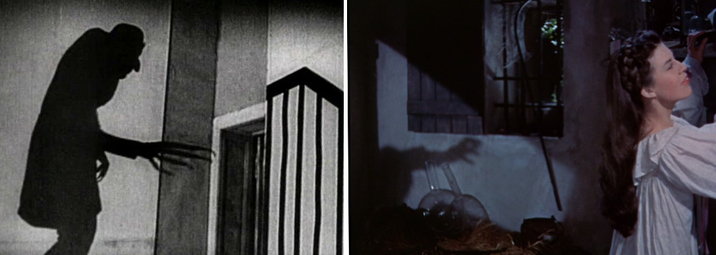

Nods to Nosferatu