Although John Barrymore Jr. (1932-2004) – also known as John Drew Barrymore – was the son of John Barrymore and Dolores Costello, his thespian parents did not provide him with an easy start in the acting profession. His mother and father separated when he was only eighteen months old, and Dolores sent him to St John’s Military Academy when he was seventeen, determined to steer him away from acting.

Undeterred, he made his film debut in the western Sundowners (George Templeton, 1950) and took many roles – most of them forgettable – on both stage and screen over the next few years. Of these, only the part of troubled teenager George in The Big Night (Joseph Losey, 1951) stands out. A slightly noirish movie, it contains hints of the simmering yet sympathetic darkness that Barrymore would bring to While the City Sleeps.

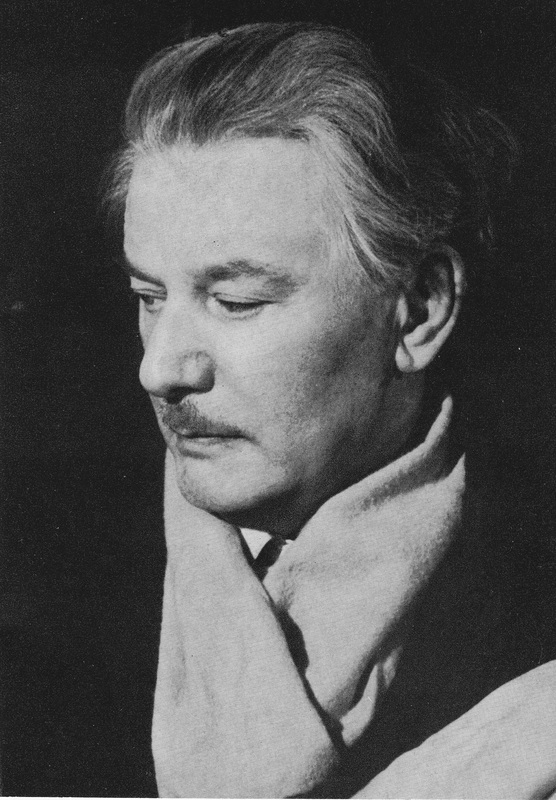

Losey was a great director but a comparative newcomer to film in comparison with Lang, who began making silent films just after the end of WWI. After directing classics such as Dr Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Metropolis (1927), M (1931) and the (possibly) anti-Nazi Das Testament des Dr Mabuse (1933) Lang left Nazi Germany, arriving in Hollywood in 1936. His American output included westerns and a series of superb film noirs including Scarlet Street (1945), The Secret behind the Door (1948) and The Big Heat (1953.) It is interesting to note that in 1951 Joseph Losey made a remake of Lang’s M – a film that provided some of the inspiration for When the City Sleeps. This was Lang’s penultimate American film before he returned to Germany.

In a previous post I explained a little about film noir including how the effect created by the deep shadows and dark fog of classic noir is typically a metaphor for the impaired moral vision of the characters: most of the time they are literally ‘in the dark’ about the wider picture, unable to discern what distinguishes the villains from the victims. While the City Sleeps breaks with this tradition: the film is brightly lit throughout, lacking Lang’s trademark chiaroscuro, and from the outset we know that John Barrymore’s character – John Manners – is the killer. So what, then, is the film about?

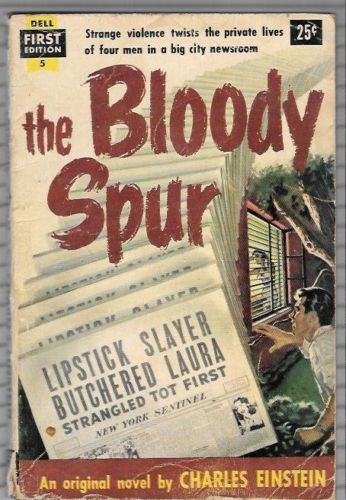

Ostensibly, it is about the hunt to catch a killer who has been murdering women in New York, and who has been dubbed ‘the lipstick killer’ after leaving the words ‘Ask mother’ scrawled in lipstick on the wall at the scene of his first murder. The story was based on a real case – that of William Heirens, who was convicted (perhaps unjustly) of multiple murders in Chicago in 1946. A journalist of that city, Charles Einsten, adapted the story into a novel entitled The Bloody Spur (1953), on which Casey Robinson based his screenplay.

There are many differences between the film and the Heirens murders, but Barrymore’s performance draws heavily on one key element – the cry for help written by Heirens wrote in lipstick on his victim’s mirror: ‘For heaven’s sake, catch me before I kill more. I cannot control myself.’

This notion that the killer is driven by an irresistible compulsion that he himself detests, was integral to Lang’s original M, in which Peter Lorre played disturbed child-killer Hans Beckert. Finally cornered by the city’s criminals that have hunted him down, Beckert empties his soul in an astonishing monologue that (thanks to Lorre’s extraordinary performance) actually elicits some sympathy: ‘I can’t help myself, I have no control over this, this evil thing inside of me – the fire, the voices the torment! It’s there all the time, driving me out to wander the streets, following me silently, but I can feel it there – it’s me, pursuing myself.’ This blurring of moral boundaries between law-breakers and law-enforcers is, of course, a recurring theme in film noir, and While the City Sleeps is no exception, even if Barrymore’s performance fails to match that of Lorre.

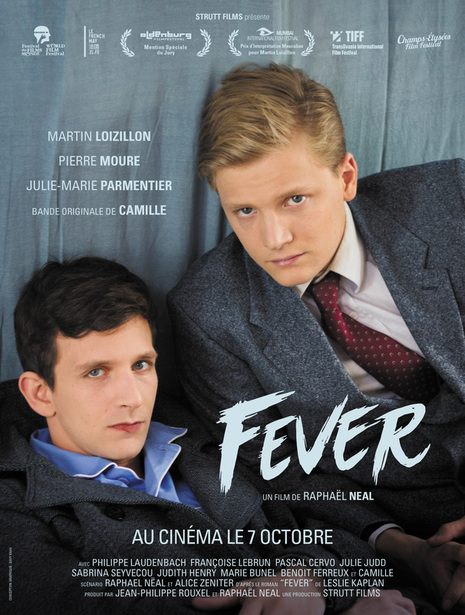

As the above poster reveals, the ‘law-enforcers’ in the film are not the police (again, a common noir trait) but ‘newsmen’ – senior staff of the Kyne Inc. media empire – who have their own motives for hunting down the killer. The film’s original title was The News is Made at Night – a clever phrase that links media activities with deeds done under the cover of darkness. Parallels are constantly drawn between the motives and actions of the killer and the media men, with a strong hint that the latter are even more reprehensible in their morals. Beckert made the same point when confronted by the criminals who – repelled by his murders and resentful of the extra police attention they had attracted – succeeded in hunting him down to enforce their own form of vigilante justice. His crimes were the result of compulsion, while theirs were choices born of financial greed and laziness.

Similarly, the Kyne agency’s interest in the murderer has less to do with justice and relates more to the desire for an exclusive story to trump their competitors. Just after the story breaks on the news, Amos Kyne – the elderly head of themedia empire, dies before he can appoint a successor. (His nurse, by the way, is played by Celia Lovsky, Peter Lorre’s former wife who was responsible for his casting in M.) This opens the way for a power struggle between three senior executives: Jon Day Griffith (Thomas Mitchell), editor of the Sentinel newspaper, Mark Loving (George Sanders) head of news wire service and Harry Kritzer (James Craig) manager of the picture agency. Kyne’s sleazy son Walter – played with relish by Vincent Price – knows nothing about what is required for the job and so offers the post as a prize: the first of the three men to identify the killer will get the coveted job. Like his father, who wanted to sensationalise news reports of the murders in order to ‘scare silly’ every woman in the country – Kyne is interested in the murder story because of its potential for media sales rather than for any concern for moral justice or sympathy for the victims. While Griffith and Loving use all their respective resources to unmask the killer (and sabotage each other’s efforts in the process), Kritzer pursues another strategy. He has been having an affair with Walter Kyne’s wife Dorothy (Rhonda Fleming) and seeks to use her influence to secure himself the job.

Director Fritz Lang with Rhonda Fleming on the set of ‘While the City Sleeps,’ filmed during the summer of 1955. One of her most memorable performances was as the double-crossing Meta in the classic film noir ‘Out of the Past’ (Jacques Tourneur, 1947.)

So what then of Ed Mobley (Dana Andrews), the anchorman on the Kyne television channel? At first sight he looks likely to be the film’s hero: a Pulitzer Prize-winner, he is engaged to Loving’s secretary, the sweet and wholesome Nancy Liggett (Sally Forrest), and disappoints both Amos and Walter Kyne in refusing to run for the boss’s job because of his apparent lack of ambition. As the movie proceeds, however, it becomes increasingly clear that Mobley and Manners have much in common.

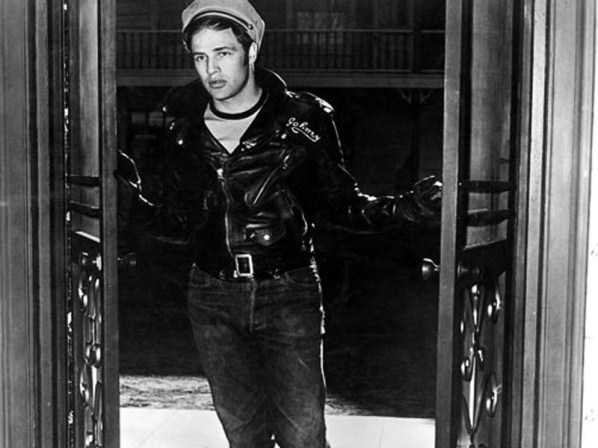

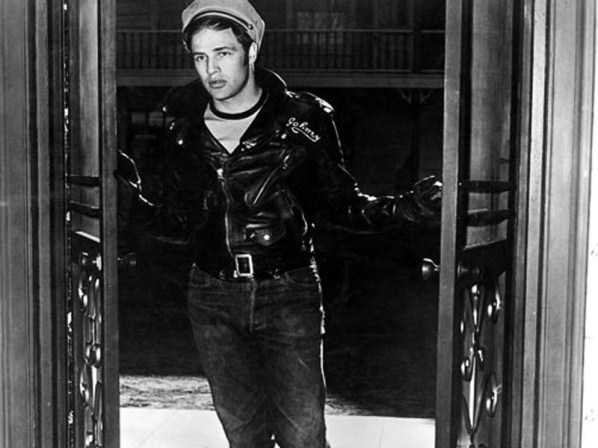

To show the parallels, we must return to the opening scenes when we first see John Barrymore in action. He appears on the screen dressed in a black leather outfit that was evidently inspired by Marlon Brando’s biker garb from The Wild One (László Benedek, 1953.)

Brando in iconic biker’s leathers. ‘

In his guise as a delivery man, Manners gains entrance to the girl’s flat by secretly placing her door on the catch as he hands over the parcel, then returning a few moments later to let himself in.

This same trick is employed by Mobley in an (unsuccessful) attempt to seduce Sally – but it at once alerts the audience to a connection between the two men. This is underlined again when Nancy hears the killer described as ‘a real nut on dames’ and responds ‘this description begins to fit Mobley.’

The truth is that – whatever their motives or justifications – all these men indulge equally in a world of voyeurism, surveillance and misogyny. Manners’ first murder begins (and is possibly provoked) when he spies on his victim in her bathroom. The next sequence introduces us to the glass-walled offices of the Kyne building, where Mobley is spying on Nancy as she resists the advances of her boss. Soon everyone in the office is watching everyone else as the power struggle escalates, and when Kritzer visits his lover Dorothy at her husband’s home, he expresses fears about sliding panels in walls and microphones hidden behind the pictures. Columnist Mildred Donner (Ida Lupino) makes a mockery of the male gaze when she teases Mobley with a slide that she suggests is a nude photograph of her, but is revealed to be a baby portrait (bottom right). Even the viewer becomes complicit in this voyeurism when the shapely Dorothy Kyne is shown in silhouette as she exercises behind a transparent screen (below), and the camera moves – at a tantalising slow speed – around the side of the screen. As the film nears its end, Manners is incited to another attack after he catches sight of Dorothy Kyne’s reflection in a mirror as she hitches up her skirt to adjust a stocking (bottom left). Rather like Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960), this is a film about scopophilia.

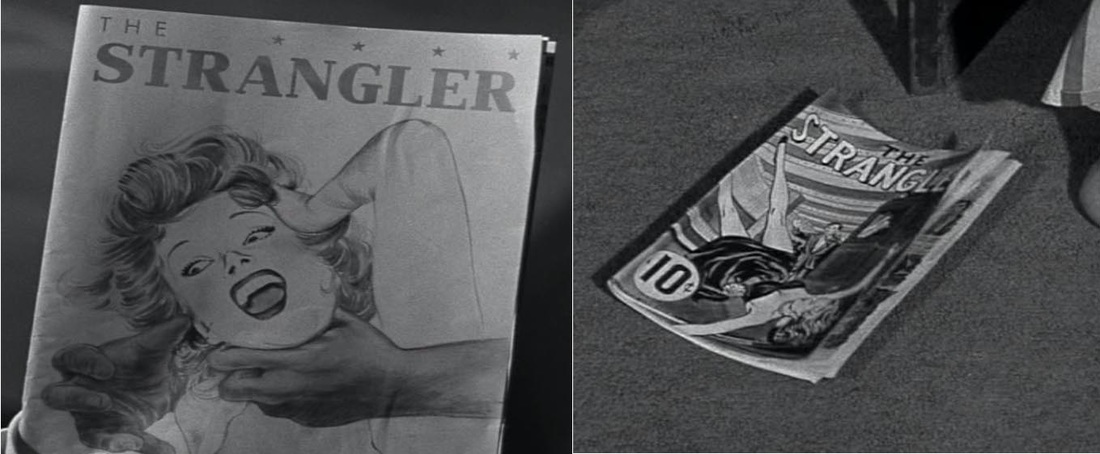

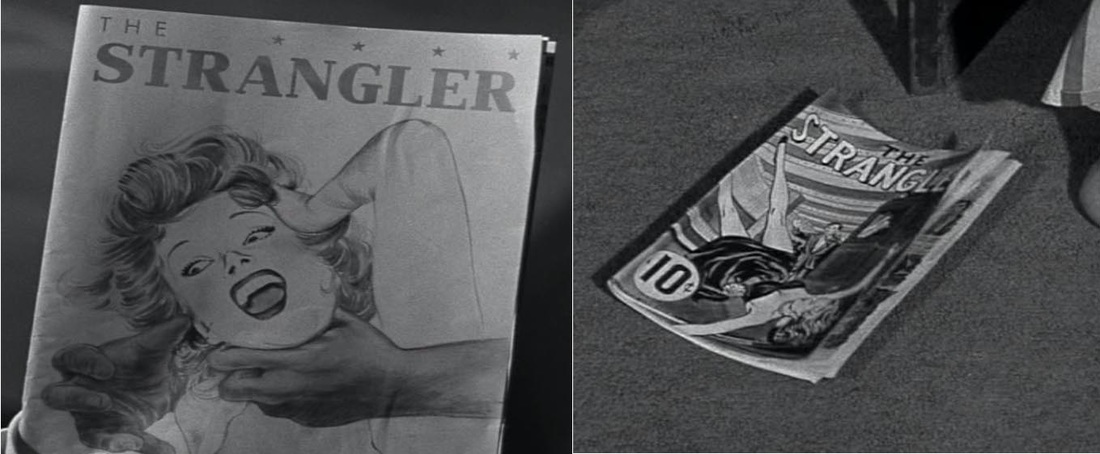

If all the characters are equally tainted with voyeurism, then why is only Manners compelled to murder? After a criminologist provides him with some clues about the murderer’s likely profile, Mobley takes a gamble and arranges a television broadcast in which he addresses the killer directly, listing all that he knows: ‘Item 4, You read the so-called comic books…Item 7. You’re a mama’s boy.’ As the broadcast proceeds, we see Manners reading comics in front of the television; he recoils in panic, almost as if the media’s insights into his private world are proof that he is actually being watched through the screen.

The comic found at the murder scene (left) and read by Manners as he watches Mobley’s broadcast (right.)

This anxiety about the harmful effect of comic books was much in the air at the time, following the recent publication of The Seduction of the Innocent (1954) by Dr Frederick Wertham, which argued that EC crime comics such as Vault of Horror, Crime Suspense and Tales from the Crypt were a factor in rising juvenile delinquency. Wertham’s study was hugely influential at this time, resulting in widespread suspicion of comic book culture. Einstein’s novel predated this hysteria and hints instead at religious fanaticism being the driving force behind the killer’s actions. The film’s portrayal of a killer with a mother fixation anticipated Psycho by four years, but had already been explored in the character of Bruno Anthony in Strangers in a Train (Hitchcock, 1950)

Kyne’s media men have no real interest in Manners’ motives of course, and only seek his capture to better their own position. The lack of moral integrity on the part of vigilantes is a theme that Lang explored in his westerns The Return of Frank James (1940) and Rancho Notorious (1952) where victims of crime struggle to reconcile their desire for revenge with the qualities of justice and mercy. In fact a great deal of Lang’s movies portray muddied distinctions between criminals, victims and the representatives of institutional justice – from The Woman in the Window (1944) in which Edward G Robinson kills someone by accident then sinks deeper into deceit trying to conceal the death – to The Big Heat (1953) which shows detective Glenn Ford struggling to stay within the law after leaving the police force to pursue his wife’s killer.

In all these films there comes a point when the protagonist’s actions reveal their true nature, and perhaps the pivotal moment in this movie is when we realise that Mobley is essentially using his fiancée Nancy as bait to catch the killer. Having goaded Manners by taunting him about his comic books and domineering mother, Mobley then announces his engagement on television, suspecting (quite correctly) that the killer will seek revenge by attacking Nancy. All they have to do is watch her closely, and the ‘lipstick killer’ will fall into the trap.

This is a fairly despicable way to treat one’s fiancée, and is made worse by the fact that we have seen Mobley’s drunken pursuit of Mildred, the seductive and highly desirable columnist who presents such a contrast to the prim and virginal Nancy. As viewers were warned earlier, Mobley and Manners – like Guy and Bruno in Strangers in a Strain – are really two peas in a pod, with one man acting as an alter ego, carrying out real crimes that represent the repressed desires of the other.

Read all about it! In Lang’s portrayal of the complex relationship between the murderer and the media, no one is innocent.

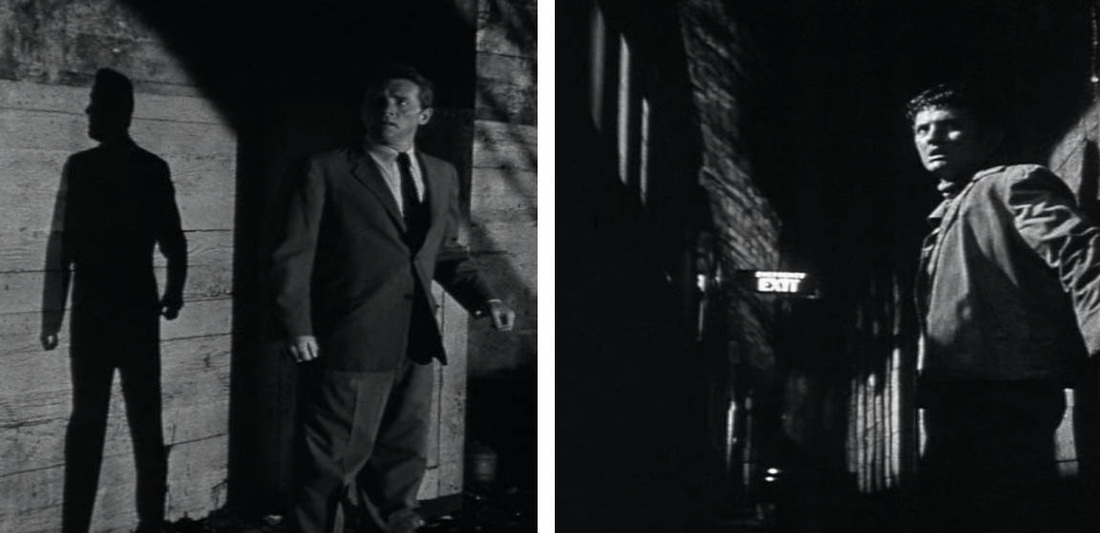

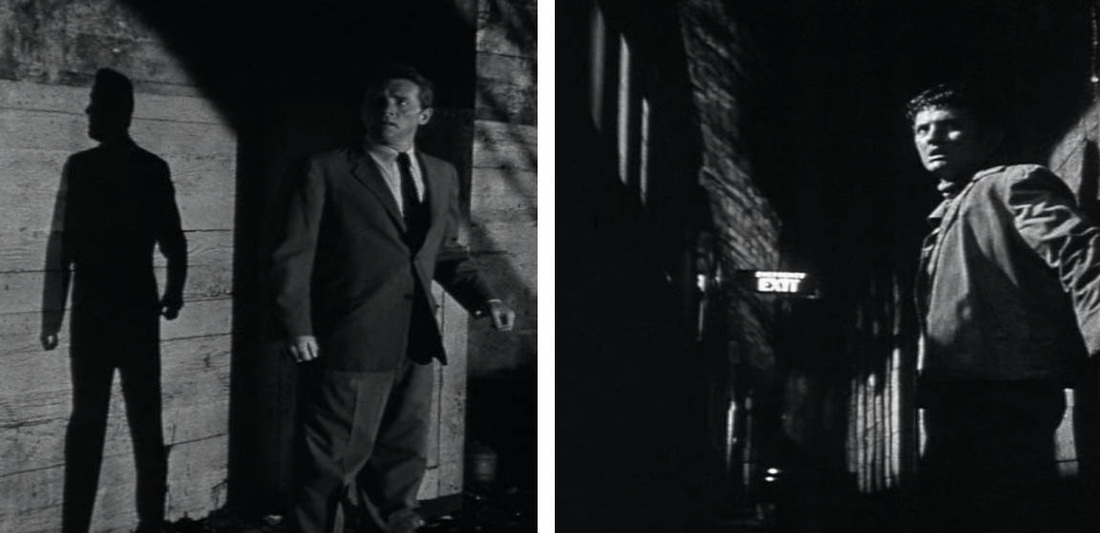

The net begins to close however, and the film climaxes in a hectic subterranean chase as Manners is pursued through subway tunnels. Although most of the film has used brightly-lit daytime interiors, this sequence returns to the dark, noirish feel of the movie’s opening frames.

In scenes reminiscent of the pursuit of Harry Lime in ‘The Third Man’, the viewer can hardly help feel sympathy for Barrymore’s character as he is hunted down like a rat

Barrymore changed his name to John Drew Barrymore in 1958 and the following year divorced his first wife, Cara Williams, by whom he had a son, the actor John Blyth Barrymore (born 1954.) He married his second wife, Italian actress Gabriella Palazzoli, in 1960, ushering in a period making historical films in Italy such as The Night They Killed Rasputin (1960), The Trojan Horse (1961) and Arms of the Avenger (1963). He returned to America in 1964 but his marriage ended in 1970. His third wife Jaid was the mother of Drew Barrymore, born in 1975, by which time his acting career had ended, his talent ruined by excessive drinking and drug-taking. While the City Sleeps remains one of his best performances, and a frustrating hint of a potential that was never fully realised.

John Barrymore with his daughter Drew

This post is part of the Barrymore Trilogy Blogathon, celebrating the ‘royal family’ of Hollywood. Details of all the other posts in the blogathon can be found

here