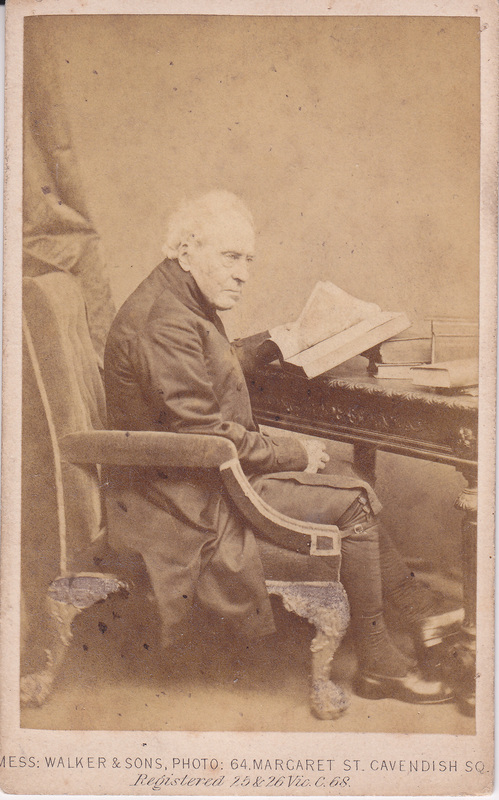

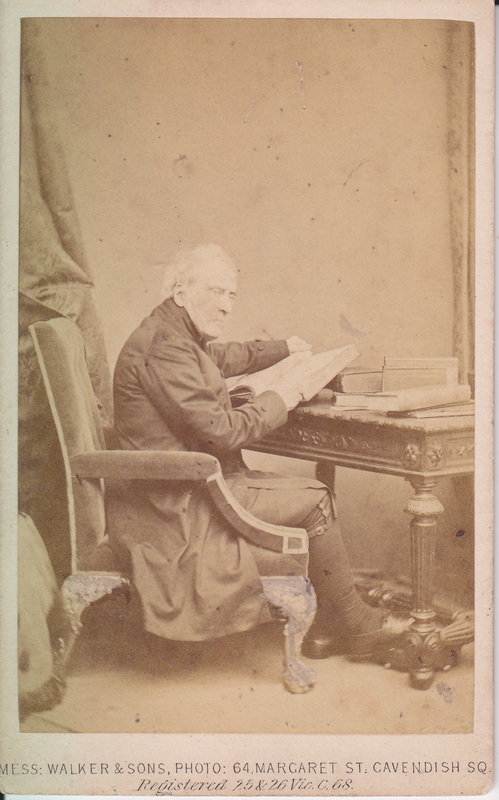

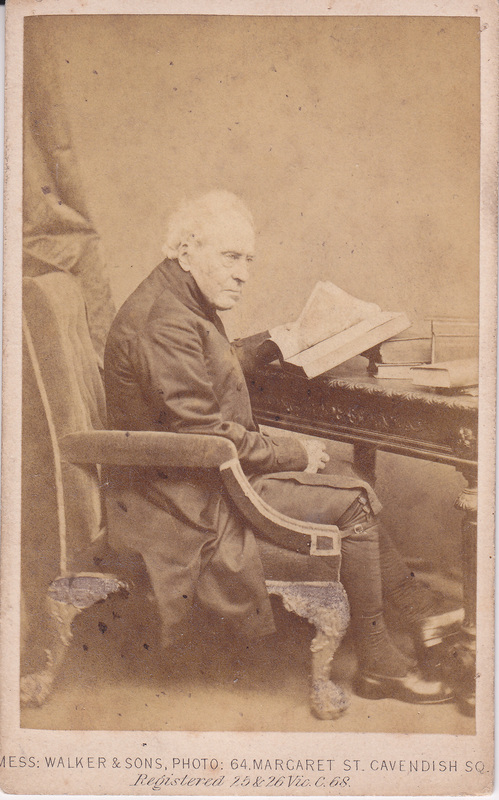

The photograph above was taken in the mid-1860s at the London studio of William Walker (1791-1867) and his son Samuel Alexander Walker (1841-1922.) Clearly visible in the picture are the gaiters worn by the bishop. This was standard ecclesiastical dress for bishops and archdeacons until the mid-20th century. Some readers may remember a BBC TV series in the late 1960s, All Gas and Gaiters, with Derek Nimmo, William Mervyn and Robertson Hare playing comical clergyman of St Ogg’s Cathedral.

Henry Philpotts (1778-1869), the redoubtable Bishop of Exeter

Phillpotts was Bishop of Exeter from 1830 until his death and ruled the diocese with an iron hand, imposing order in a region that had long been disorganised and demoralised. He was, however, a pugnacious character who relished conflict and detested compromise. Walker’s portraits capture the bishop’s forceful character – the massive brow, granite features and clenched jaw support Owen Chadwick’s description of him in action: ‘exposing opponents’ follies with consummate ability, a tongue and eyes of flame, an ugly tough face and vehement speech.’ (The Victorian Church Vol.1)

Unsurprisingly, Phillpotts was embroiled in controversy throughout his life. Local conflicts included his long-running feud with Thomas Latimer, editor of Western Times, the Exeter surplice riots (1844-45) – which saw violent mobs protesting in Sidwell Street – and the Gorham case (1847-50), a long-running dispute over the bishop’s refusal to allow the Rev. George Gorham to take up his appointment in Brampford Speke. Philpotts believed Gorham’s views on baptismal regeneration to be out of line with Anglican orthodoxy, but when the bishop’s judgment was overruled by an appeal court, High Churchmen were appalled at the idea of secular authorities overruling the episcopate on matters of religious doctrine.

St Peter’s Church in the quiet village of Brampford Speke, a short distance from my home. It was Phillpotts’ refusal to ordain the Rev. George Gorham as vicar here in 1847 that led to deep unrest within the Church of England.

The Lower Cemetery in Exeter, showing the wall dividing the Anglican graves from those of Nonconformists. Phillpotts consecrated the Anglican side on 24 August 1837 but refused to have anything to do with the ‘dissenters.’

Although it is tempting to dwell on the conflicts and controversies, Phillpotts made many positive contributions to the diocese of Exeter, including restoring part of the cathedral, founding a theological college and library, and working with Lydia Sellon to revive religious communities for women. He didn’t like the city much, however, and preferred to live in Torquay rather than in the episcopal residence attached to the cathedral.

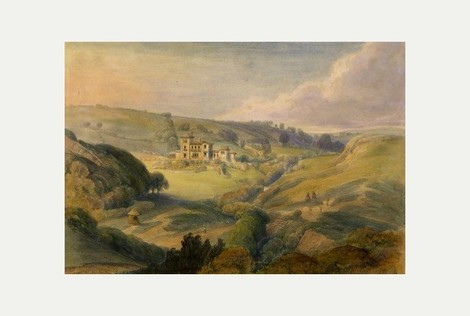

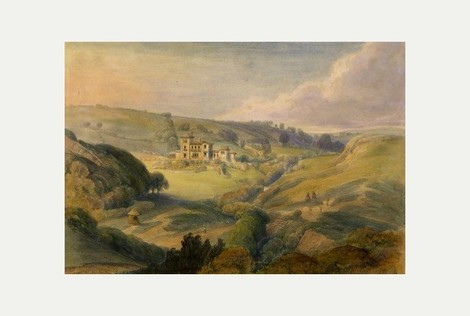

Bishopstowe, Phillpotts’ residence in Torquay and the place where he died on 18 September 1869

Celebrity cards like these were inexpensive to buy – typically between 1/ and 1/6d – and would be sold in stationers shops or other outlets. There was an insatiable market for collecting carte-de-visites of famous people in the 1860s, though one wonders how popular Bishop Phillpotts’ portrait was among collectors, given his unpopularity and fearsome reputation. I remain curious to know more about the person who originally bought this pair of cards. Were they an admirer of the bishop? Did they acquire the cards to go in an album with cdvs of other church dignitaries, or were they collecting cards of local interest to the Exeter area?

Original albums of Victorian cartes-des-visites regularly come up for sale, but often we know little about the way these collections were put together. How often were people buying cards? How much was acquired as part of a clear collecting strategy and how much was picked up on arbitrary impulse, according to what was available or looked appealing? What personal use did the collector make of the images he had acquired? Was the album taken out in the evenings to be pored over as we might do with a glossy ‘coffee-table’ book?

Questions such as these invite comparisons with modern habits of collecting, as well as highlighting the extent to which the meaning and nature of celebrity status has changed over the last 150 years. Some people might be bemused today at the notion of a man like Bishop Phillpotts being regarded as a celebrity, but his contemporaries would be equally baffled, if not more so, at the activities and achievements of those accorded the status of celebrity by the modern media.