Elisabeth von England (Elizabeth of England) was published in 1930, and was the work of Theodor Tagger (1891-1958), better known under his pseudonym of Ferdinand Bruckner. He legally changed his name to Bruckner after the war, so I’ll continue to refer to him in this way. Broadly speaking, his life paralleled that of A.W’s, with his early life spent between Vienna and Berlin, followed by an interest in music and poetry that drew him into the theatrical world. He founded the Berlin Renaissance Theatre in 1922, took over the Kurfürstendamm Theatre in 1927, published Krankheit der Jugend (The Pains of Youth, 1929), Die Verbrecher, (The Criminals, 1929) and Elisabeth von England before migrating to Paris after the Nazis came to power in 1933. In Paris he wrote Die Rassen (The Races), the first anti-Nazi play to be written by an exile. It had its premiere at the Schauspielhaus in Zurich in 1934. He migrated to America the same year as A.W., publishing another historical play – Napoleon der Erste in 1937 – and joining the German-American Writers Association, the fellow members of which included Thomas Mann and Oskar Graf. During the war he worked for Paramount Studios and did not return to Germany until 1953 when he translated Miller’s Death of a Salesman for a production. He worked as an advisor to the Schiller Theater in Berlin until his death there in December 1958.

Bruckner wrote Elisabeth von England while working as a theatre director and did not reveal his authorship until its success had been proved. The play draws on Lytton Strachey’s Elizabeth and Essex: a tragic history (1928), focussing on the relationship between Queen Elizabeth and Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. It is a wordy piece, heavy on psychoanalysis (Freud wrote to Strachey on Christmas Day 1928 offering a detailed treatment) in its portrayal of the complex psychology of the ageing queen in her relationships with three men: her father Henry VIII, the much younger and attractive Essex, and the religious zealot of Philip of Spain, to whom she is also attracted.

Essex had been part of the royal court since the late 1580s and was a favourite of the queen. Aware of this, he tended to her sympathy for granted, pushing his luck several times with occasions of insolence and disobedience. Other factions at court resented his behaviour, and a disastrous attempt at rebellion in February 1601 led to the Earl’s arrest and beheading on Tower Hill a few days later.

Using a device made popular in Berlin by Edwin Piscator since the 1920s – the Simultanbühne or split stage – Bruckner’s The Criminals was set in a tenement house which was cut away so that the audience could watch action taking place simultaneously in different parts of the building. This time, the split stage was used in the final scene of each Act to show the respective situations in the English and Spanish courts as they responded to events. By asking the audience to compare the behaviour of the two courts, the play was also inviting comparisons to be made with contemporary events in the real world. England’s pragmatism and dislike for war was contrasted with Spanish warmongering and sense of destiny.

There are elements of this in AW’s performance as Prince Albert in Victoria the Great (1937) and Sixty Glorious Years (1938), and I discuss this in my forthcoming conference paper ‘Walbrook’s Royal Waltzes’ which is due for publication later this year in The British Monarchy on Screen (Manchester University Press.) The paper also looks at AW’s earlier stage performances in Schiller’s Maria Stuart.

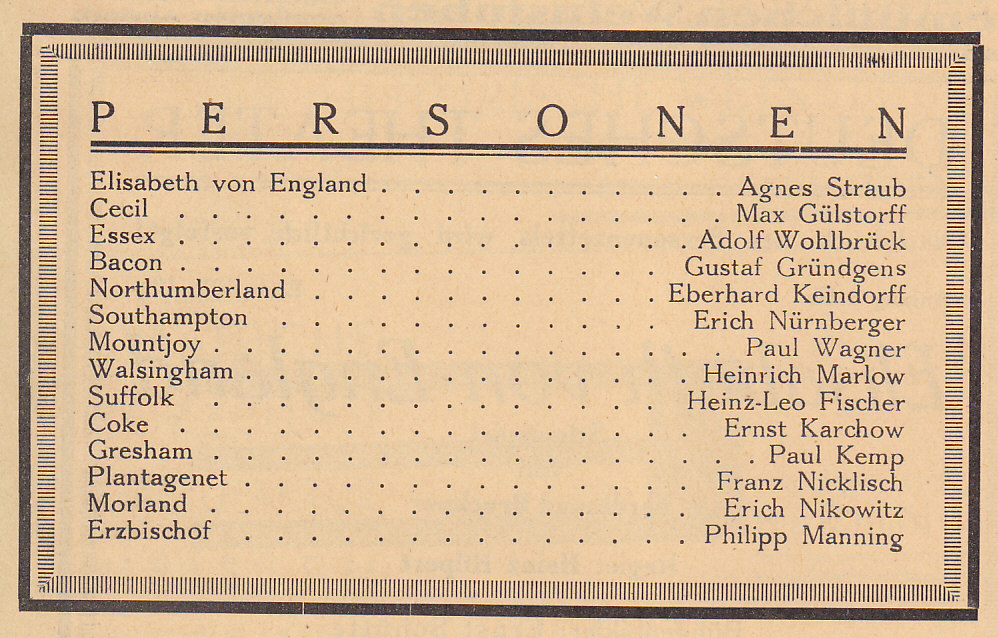

Returning to Bruckner’s play, its mix of historical drama and gripping psychology proved popular. Elisabeth von England opened in November 1930 and ran for 122 performances. The cast looked liked this: