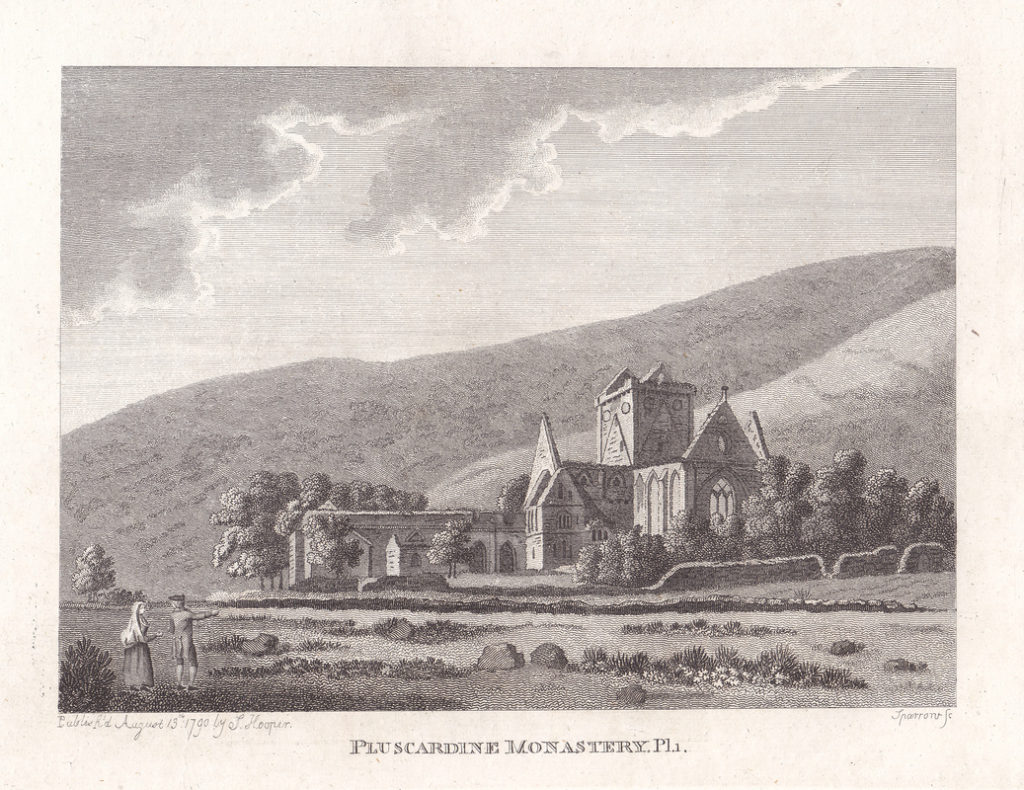

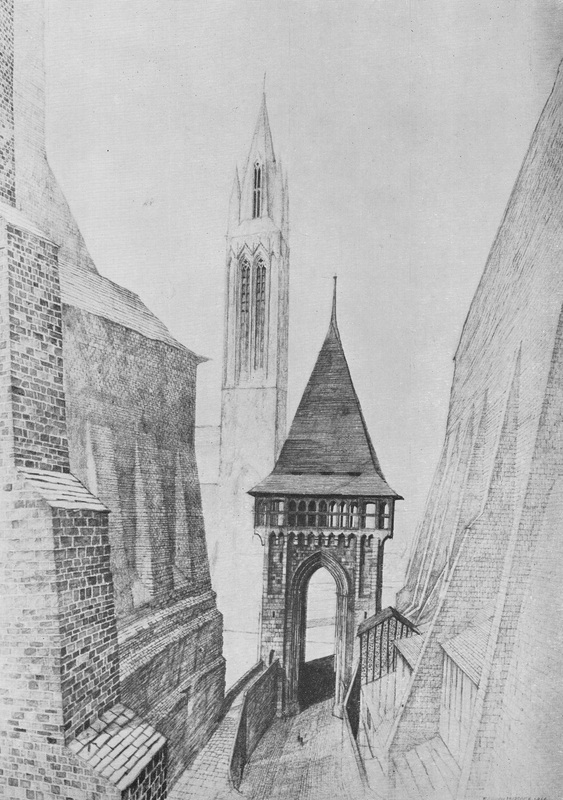

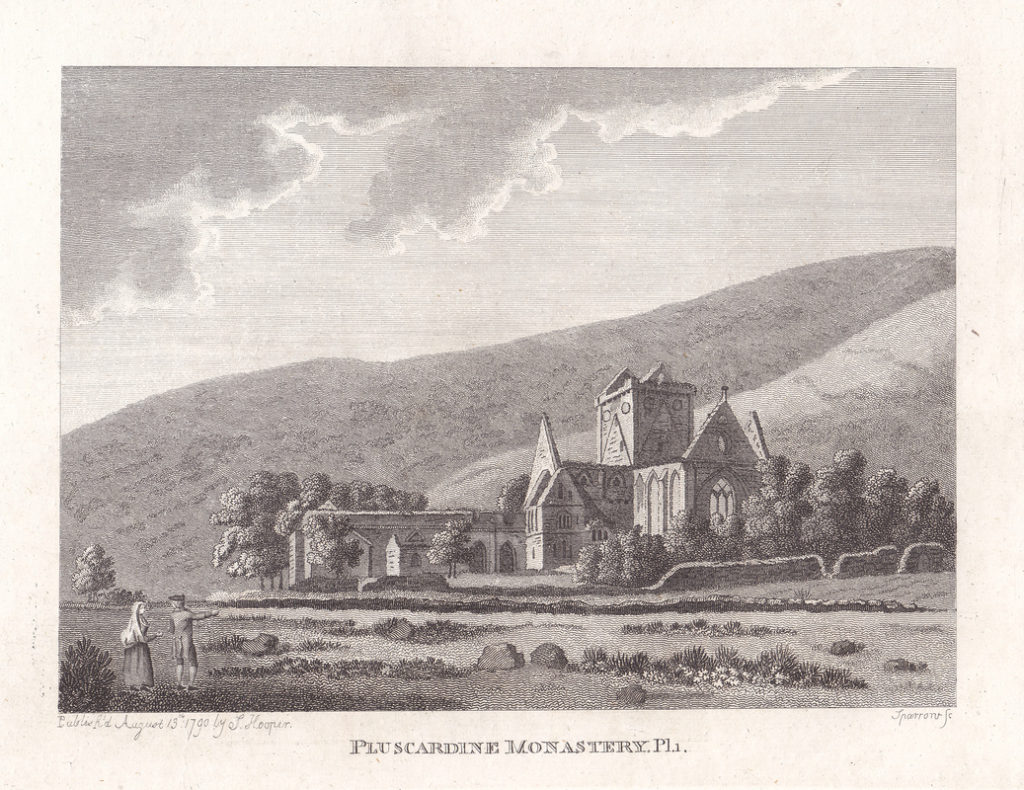

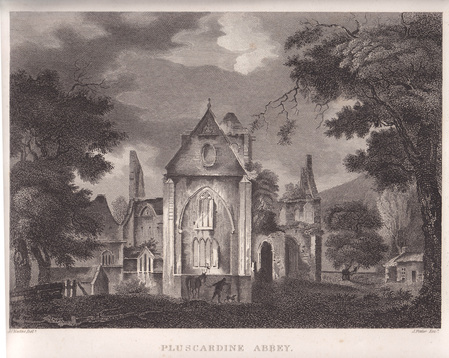

‘Pluscardine Monastery’ engraved in 1790 by Samuel Sparrow, from Francis Grose’s ‘Antiquities of Scotland’ Vol.II, (London: S Hooper, 1797)

Mark how the Ivy with Luxuriance bends

Its winding Foliage through the cloister’d Space,

O’er the green Window’s mould’ring Height ascends,

And seems to clasp it with a fond Embrace – George Keate, The Ruins of Netley Abbey (1764)Sometimes I wonder if there is some curious kink in human psychology that makes the sight of a crumbling, ivy-clad ruin more appealing to our eyes than a similar structure in pristine condition. Poets, antiquarians and artists have found ruins an almost endless source of material for their studies and meditations, offering a frisson of Gothic terror by moonlight or a moral exemplar for the vanity of man and the transience of earthly glories. After some time looking at old prints and poems about ruined abbeys and churchyards, one starts to recognise the recurring themes – sprouting foliage, owls in moonlight, skeletal cloisters, lonely figures hemmed in by overhanging walls and shadows. Even as 18th century travellers give way to Victorian tourists, and engravings yield to Kodak prints and tuppenny postcards, the same picturesque conventions persist.Today’s blog presents a brief survey of images of Pluscarden Abbey, which was abandoned after the Reformation and remained in a ruinous state for some 350 years. Being somewhat off the beaten path it was never subjected to the intense scrutiny of monastic ruins such as Fountains or Rievaulx, but the 25 pictures below (all scanned from prints and postcards in my collection, apart from the Girtin watercolour) will hopefully offer some insight into the way in which a single structure has been depicted by artists and photographers over a period of 150 years.

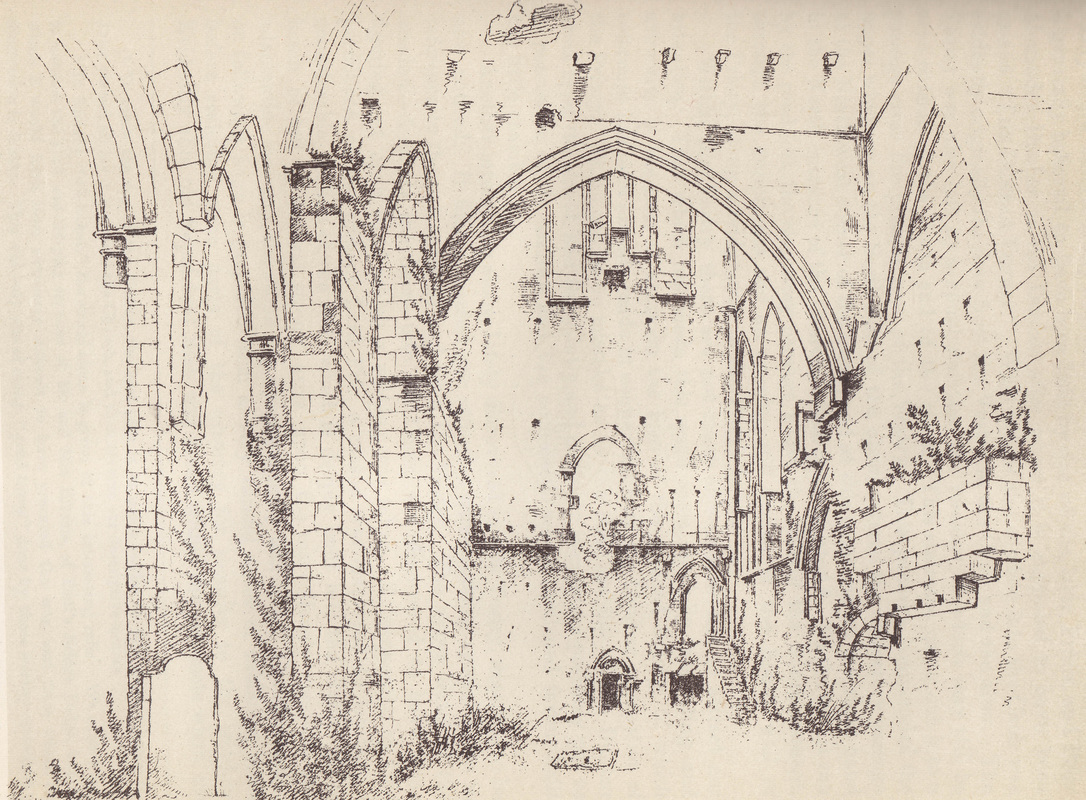

John Claude Nattes was a founder member of the Society of Painters in Water Colours in 1804, two years after Girtin’s death. The Society broke away from the Royal Academy, who did not accept watercolour painting for its exhibitions. If Nattes ever executed watercolour paintings of Pluscarden, they have not survived, but the delicacy of these pencil sketches is still impressive.

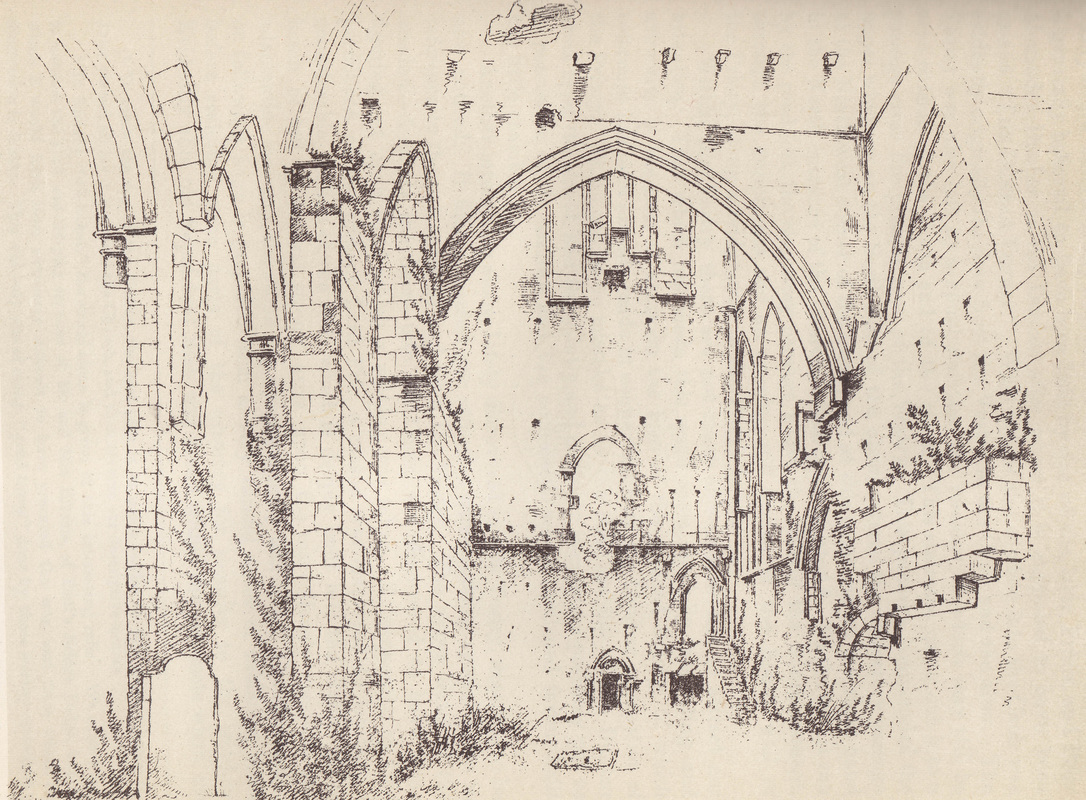

‘Inside View of Pluscarden’, drawing made on 7 October 1799 by John Claude Nattes

Thomas Girtin’s watercolour shows the view from the opposite side, looking from the north west through the ruined cloisters towards the walled-up arch that would have connected to the nave. Before Girtin, watercolour had been regarded as suitable only for preliminary sketches and not a suitable medium for serious landscape painting, far less Academy exhibitions. Girtin changed all that with his evocative paintings of ruined monasteries, beginning the Romantic tradition of watercolour landscapes.

‘Pluscardine Abbey,Elgin’ (1793), watercolour by Thomas Girtin. The original painting is now in the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut.

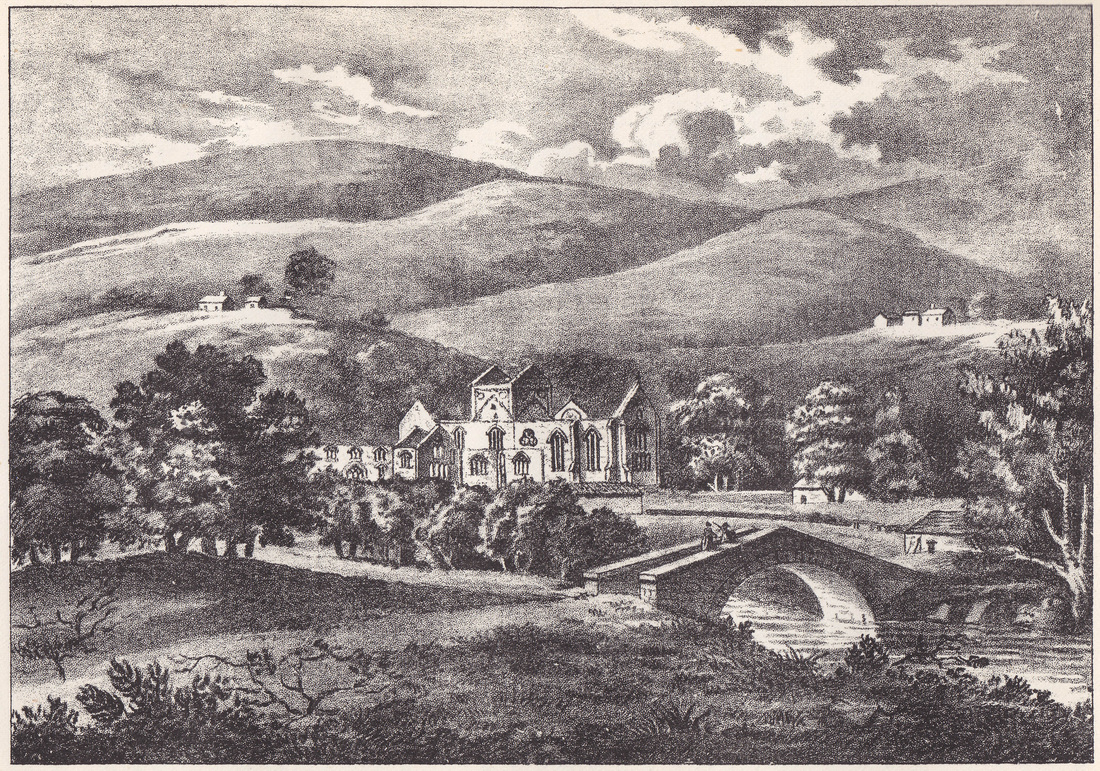

This view of the ruined monastery from the SE takes a few liberties with both the setting and the structure, such as exaggerating the height of the hills. Grose wrote ‘This Priory stands on the North side of the River Lochty, about six miles South West from the town of Elgin, near the entry of the valley, at the foot of the North hill, which reverberating the sun beams, renders the place very warm.’ This sense of pleasant weather – the engraving is dated 13 August 1790, so presumably a summer’s day – is matched by the open aspect and bright airy feel of the view.

Another Nattes drawing from the same day, showing the undercroft which was later filled in.

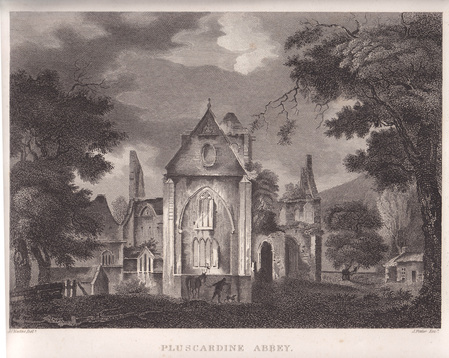

‘Pluscardine Abbey’ engraved by James Fittler from a drawing by Nattes, from ‘Scotia Depicta’ (London: W.Miller, 1804)

Fittler’s engraving introduces various picturesque elements that are absent from Nattes’ more precise drawings: a gloomy sky, thick foliage not only framing the view on both sides but overhanging slightly to convey a sense of of nature’s ability to overpower the works of men, and some human interest in the form of a lone walker with a dog at his feet, leading his horse through the ruins.

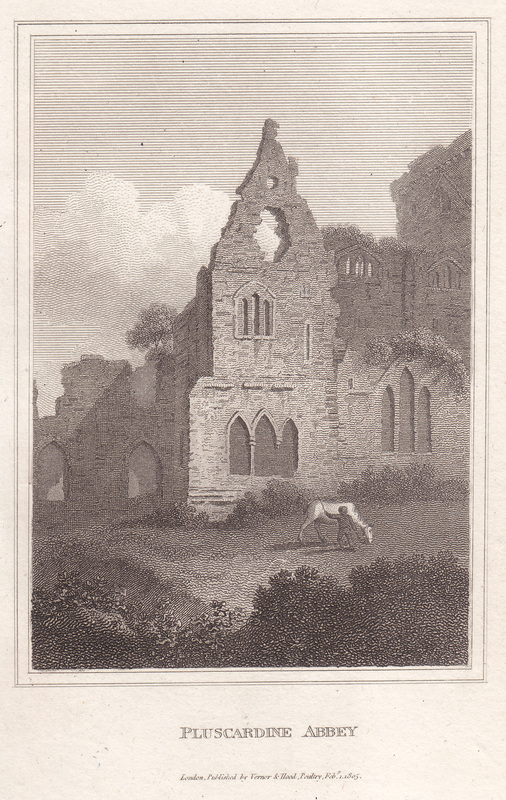

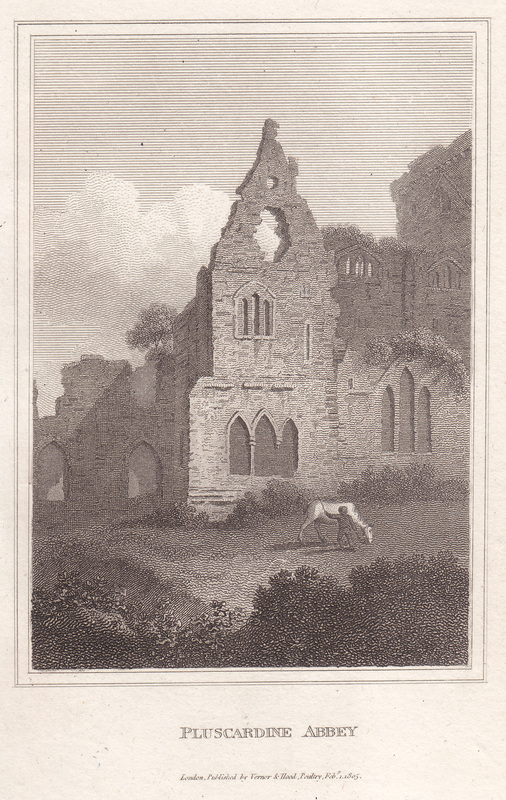

The work of an unknown artist, published 1st February 1805 by Verner & Hood. This view shows the east end of the Lady Chapel, although its height has been exaggerated for dramatic effect.

From John Stoddart, ‘Remarks on Local Scenery and Manners in Scotland in the Years 1799 and 1800’, (Vol.II) London: John Miller, 1802

This print also introduces the figure of man and horse – a typical pastoral image. Pictures of ancient ruins often showed shepherds or cowherds grazing their animals – a reference to Biblical prophecies such as Isaiah 5:17 and 7:25, which warned that cultivated places would one day fall desolate and be fit only for animals.

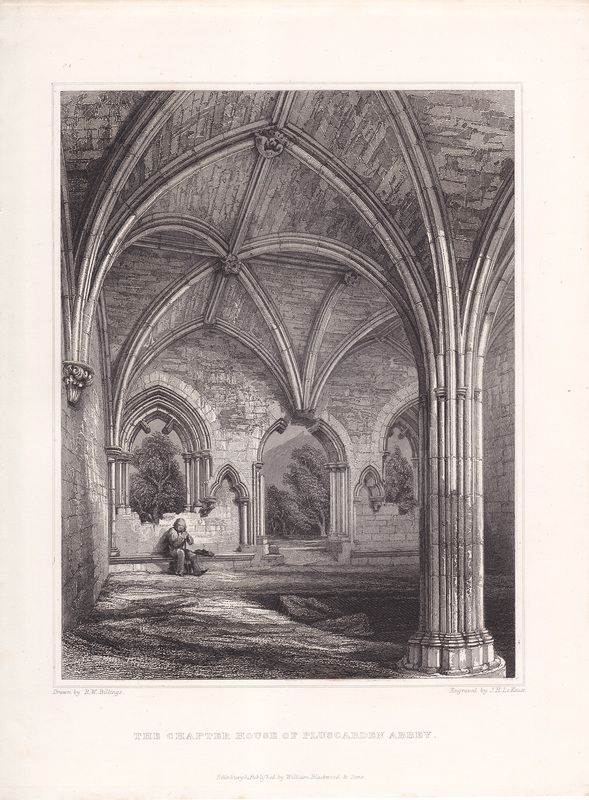

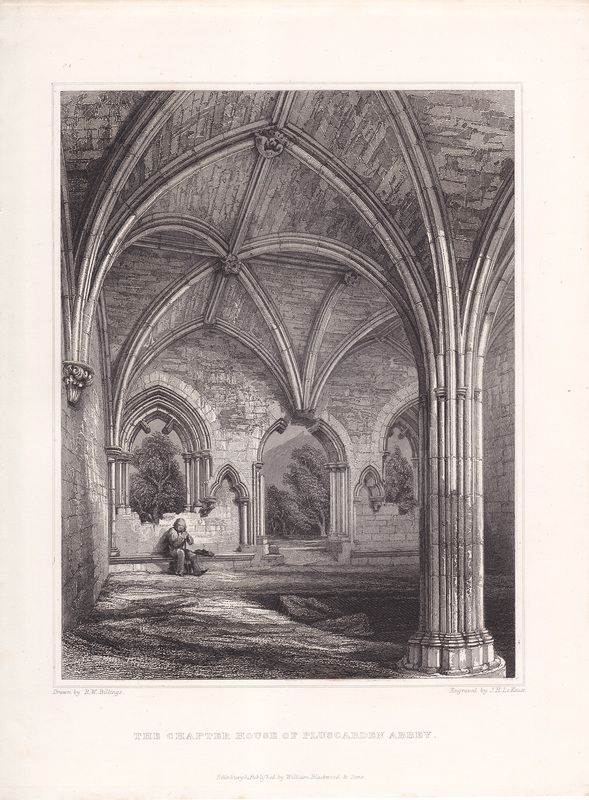

The monastery is roofless in all these views, but James Duff, the 4th Earl of Fife and owner of Pluscarden from 1811 to 1857, was the first to carry out major renovations. His concerns were domestic rather than religious: the dormitory was re-floored in the 1820s to allow dancing, and the ground floor rooms were fitted up for use by shooting parties. The local Presbyterian kirk began worshipping in the monks’ chapter house (below) where they installed a 17th century pulpit from Elgin.

The Chapter House, Engraved by Robert W. Billings and Engraved by John H Le Keux for Vol. IV (1852) of ‘The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland’

Billings’ accurate and detailed drawings still retain elements of Romantic sensibility – note the lone figure with lowered head, his gaze directed towards the gravestones in the floor. Reflecting upon one’s own mortality and the inevitable passage of time was one purpose of visiting ruins.

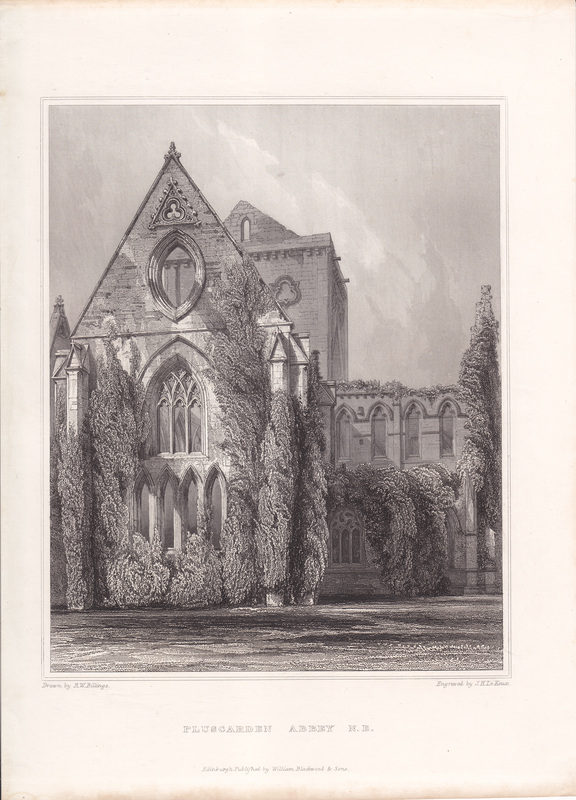

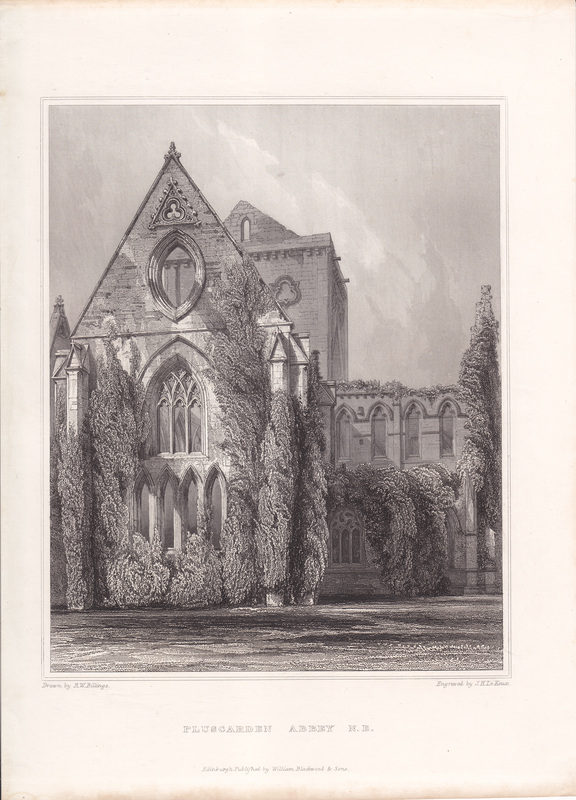

View from the NE, showing the extent to which the ruin were clad in ivy. – Billings & Le Keux (1852)

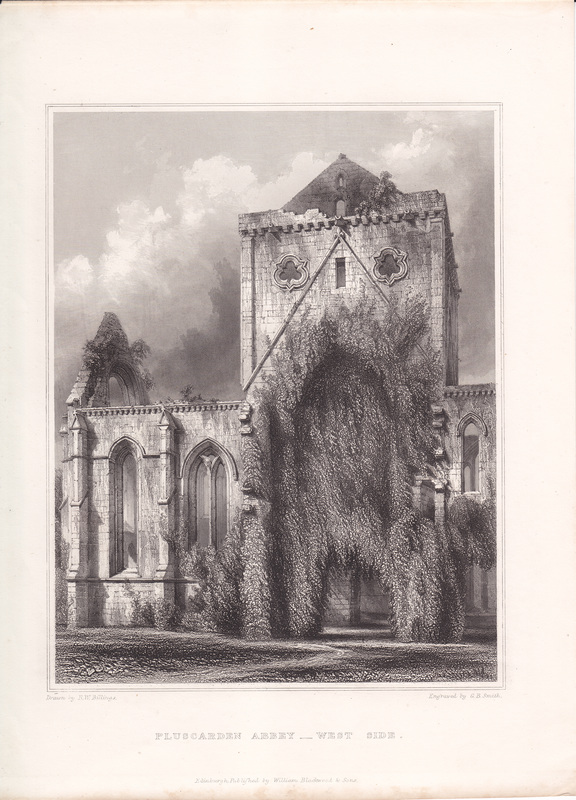

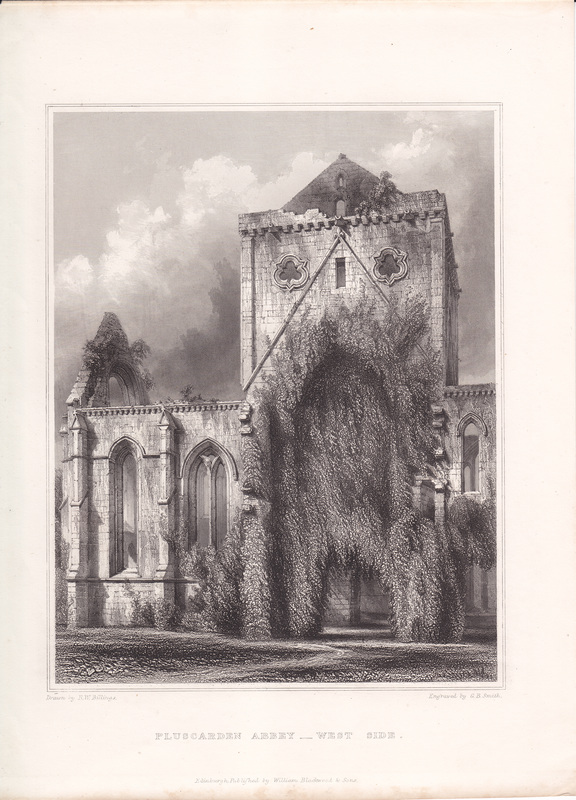

View from the West Side, – Billings (1852), engraved this time by George Belles Smith

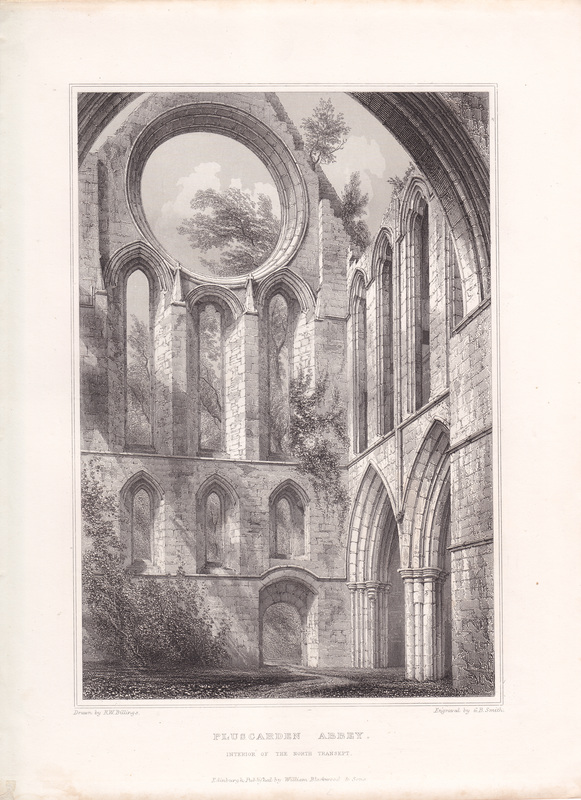

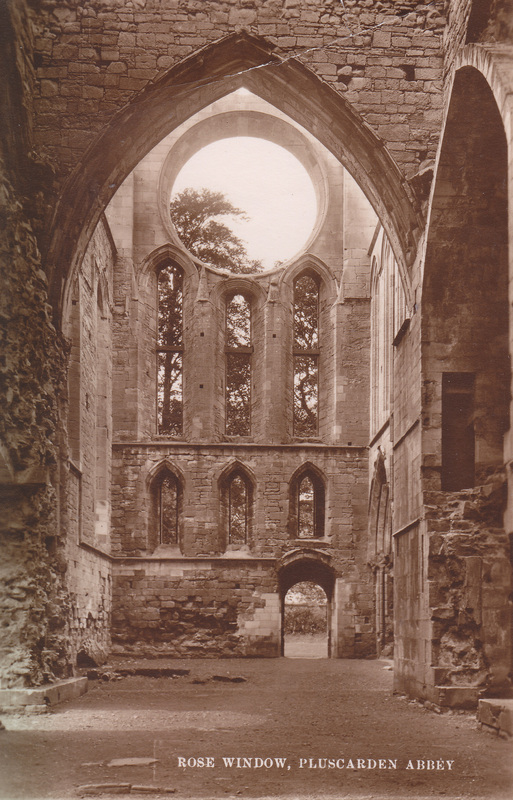

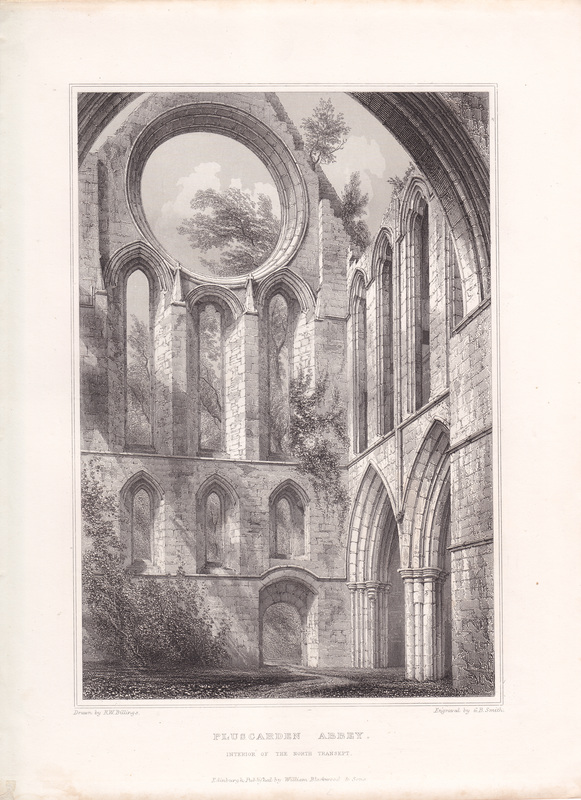

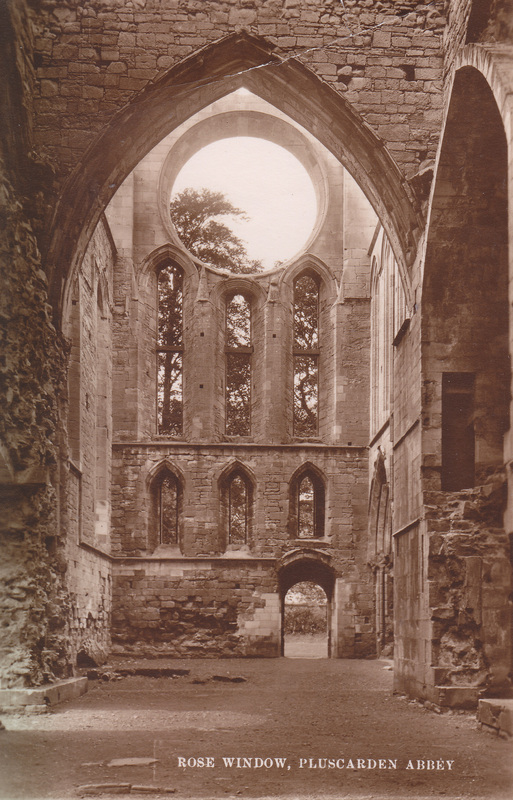

Interior of the North Transept, Billings & Smith (1852.) Here, the large rose window is shown entirely open, whereas the photographs below show that it was in fact partially bricked up.

Pluscarden remained in the hands of the Earls of Fife until the end of the 19th century, by which time they had moved further up the aristocratic scale: the 6th Earl became the 1st Duke of Fife after marrying Queen Victoria’s grand-daughter, Princess Louise, in 1889. By this time the ruined monastery had become a popular visitor attraction for daytrippers and Sunday picnics on the lawn, for which a small admission charge was paid at the gate.

Stereoview showing the interior of the north transept, taken from beneath the central tower. Published and photographed by H H Bennett, Kilbourn City, Wisconsin.

The print on this stereocard claims that this view was ‘published and photographed’ by Henry Hamilton Bennett (1843-1908), a pioneering photographer from Kilbourn City, (now Wisconsin Dells) in Wisconsin. At the other end of the card, the title ‘Wanderings among the Wonders and Beauties of Wisconsin Scenery’ – also printed in Gothic blackletter type – has been scored out, and ‘Interior View of Pluscarden Abbey, Scotland, No.8’ printed in a different typeface underneath.

This puzzled me, as I didn’t think Bennett had ever travelled to Scotland. Thankfully, Alan J Hanson, the Historic Site Co-ordinator of the Bennett Studio in Wisconsin (which has preserved Bennett’s studio and photographs) was able to help. It appears that Bennett’s mentor –

Milwaukee industrialist William Metcalf – came over to Scotland and either took the photo himself or commissioned a local photographer to do so, and then sent the negative back to Wisconsin for Bennett to print. These would then be sold alongside Bennett’s images of the scenery around Wisconsin Dells, which were very popular with tourists. The image is very similar to that taken by Henry Gordon (below.)

Pluscarden, 3rd September 1880. Heliogravure print by Armand Durand (1831-1905), possibly from an original pen drawing by Sir George Reid F.S.A. (1841-1913)

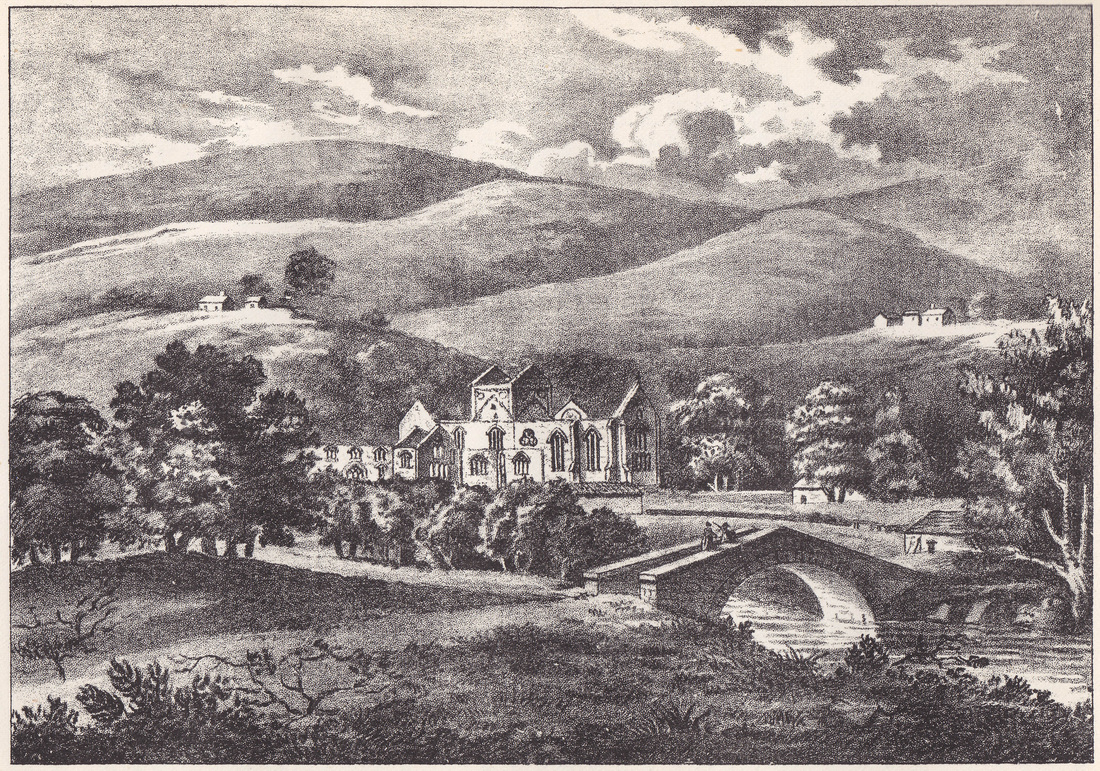

This print shows the view when approaching from Elgin, with Heldon Hill and the Monaughty Woods rising up on the north side of the monastery.

This little carte-de-visite was the work of by Aberdeen photographer Henry Gordon,.probably in the 1880s The view is from under the main tower, looking down from the dormitory staircase towards the north door.

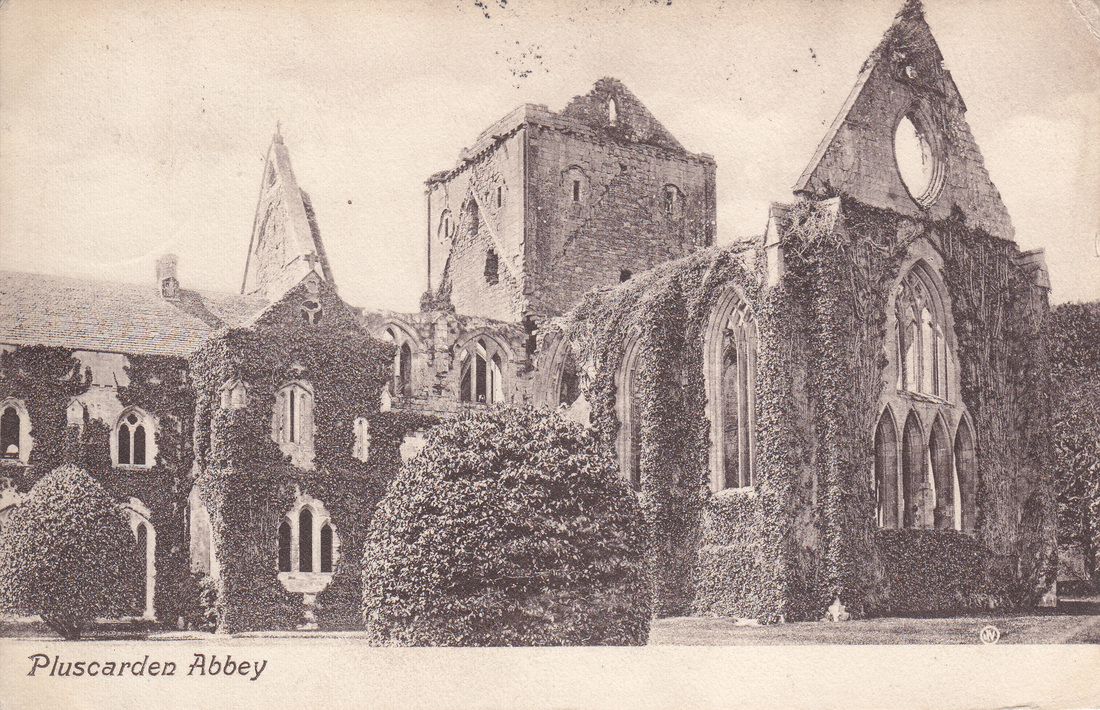

Another cdv-sized photograph by Henry Gordon, who had premises at 3 Belmont Street (1876-1887), 92 Rosemont Place, (1883-1895), 45 School Hill, (1887-1890) and 38 St Nicholas Street (1893-1900), all Aberdeen. The carefully pruned shrub indicates how much the grounds had been domesticated and gentrified, in comparison with the appearance of the 18th century prints.

This view, taken around the same time with a camera set up in almost the same spot as Henry Gordon’s, was published by James S. Pozzi, author of a Guide to the Ruins of Elgin Cathedral (Elgin, 1892)

Frontispiece to ‘The History of the Religious House of Pluscardyn’ (Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier, 1881) by the Rev Simeon Ross Macphail.

The above picture is clearly derived from the photograph reproduced on Pozzi’s postcard, rather than Gordon’s which shows much thicker ivy. Macphail’s book was the first major study of the history of the monastery, and – despite being a Free Church minister with a strong antipathy towards Roman Catholicism – his work combined careful scholarship with a sense of deep affection for the place. It remains unsurpassed, notwithstanding the publication of Peter Anson’s A Monastery in Moray (London: SPCK, 1959.)

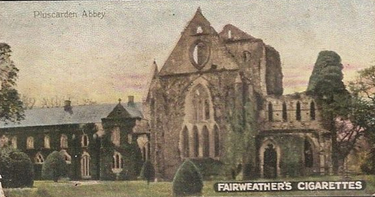

A nicely-coloured cigarette card, from the late 19th century: No.4 of ‘A Series of 50 Historic Buildings’ issued by Fairweather & Sons, a tobacco company founded in Dundee in 1835. Despite this constant reference to ‘Pluscarden Abbey’, the monastery was never more than a priory in medieval times. Its first ever abbot was not elected until 1974.

In 1897 the priory and estate of Pluscarden were purchased by John Patrick Crichton-Stuart, the Third Marquess of Bute (1847-1900.) A great patron of the art and a serious antiquarian scholar, he had plans to restore the priory over a ten-year period at a cost of around £200,000. Under the direction of architect John Kinross, excavations were undertaken, work began on the church, and a team of artists, craftsmen and masons were hired.

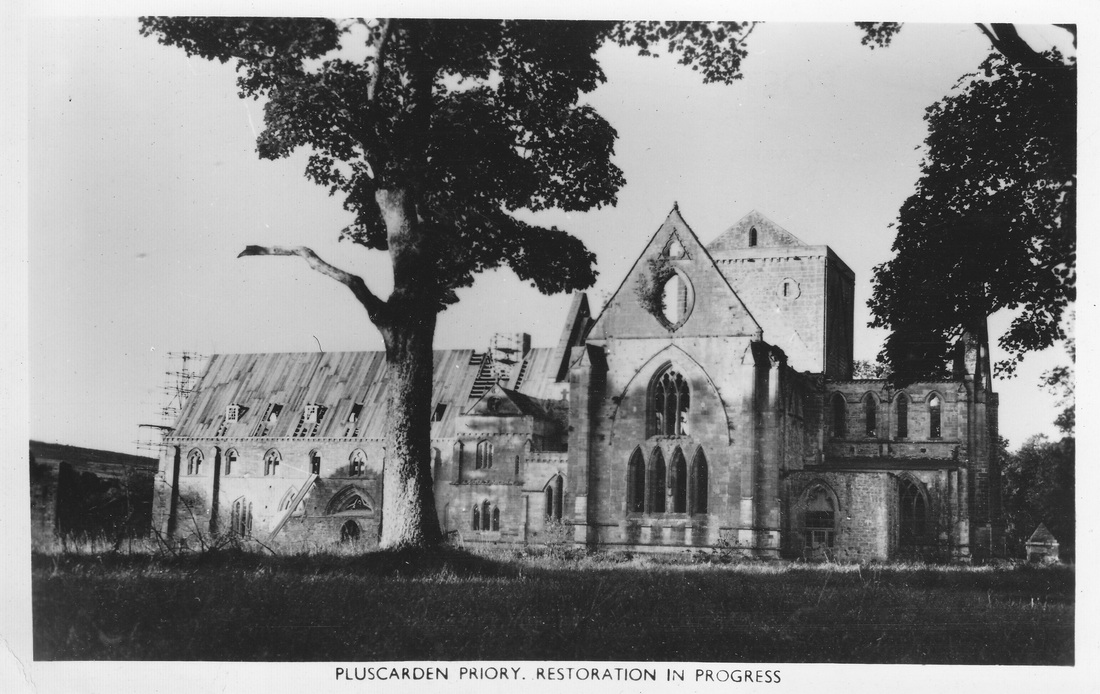

These two postcards were has taken from more or less the same spot, at slightly different times of year, and show the first stages of restoration: the removal of the dense layers of ivy which had been regarded as so picturesque by past generations. Nothing of course, was quite as romantic as viewing the ruins by moonlight….

Pluscarden by Moonlight. A tinted version of one of the view above

The death of the Marquess in 1900 brought work to an abrupt halt.

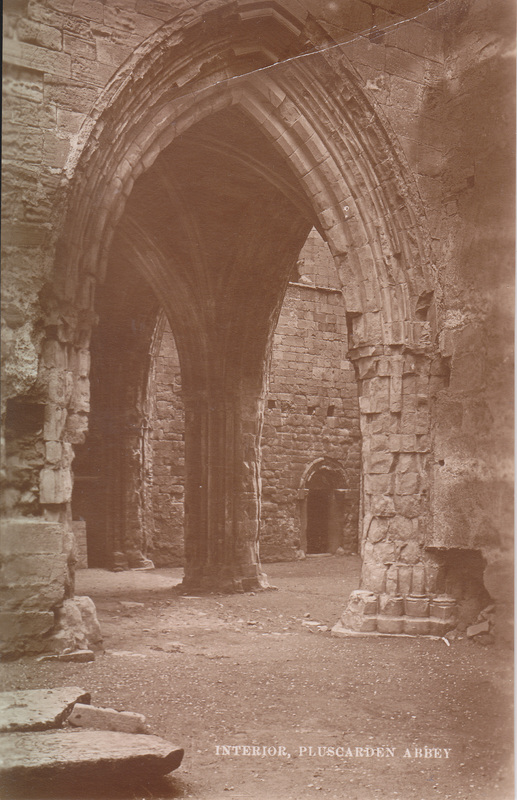

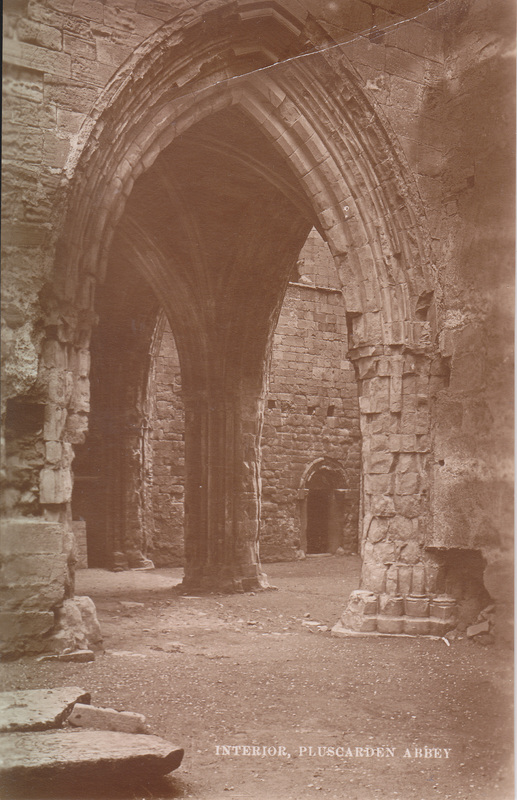

Nevertheless, the grounds were now in excellent condition, and this postcard shows the neatness of the pathways leading around the ruins. Prior to the Reformation, construction of the monastery had continued over three centuries, incorporating a variety of historical styles; this archway is actually a later medieval imitation of an earlier architectural style. Going for the ‘retro’ look is nothing new.

Another postcard view of the rose window and north door

From the same set ca.1900 looking towards the entrance door to the Lady Chapel

Another postcard view, this time taken from inside the calefactory and looking out into what would have been the cloister garth

The same doorway from the other side, showing the neat gravel paths and hedges that had been laid out in the priory grounds. The Norman archway is visible at the end of the path.

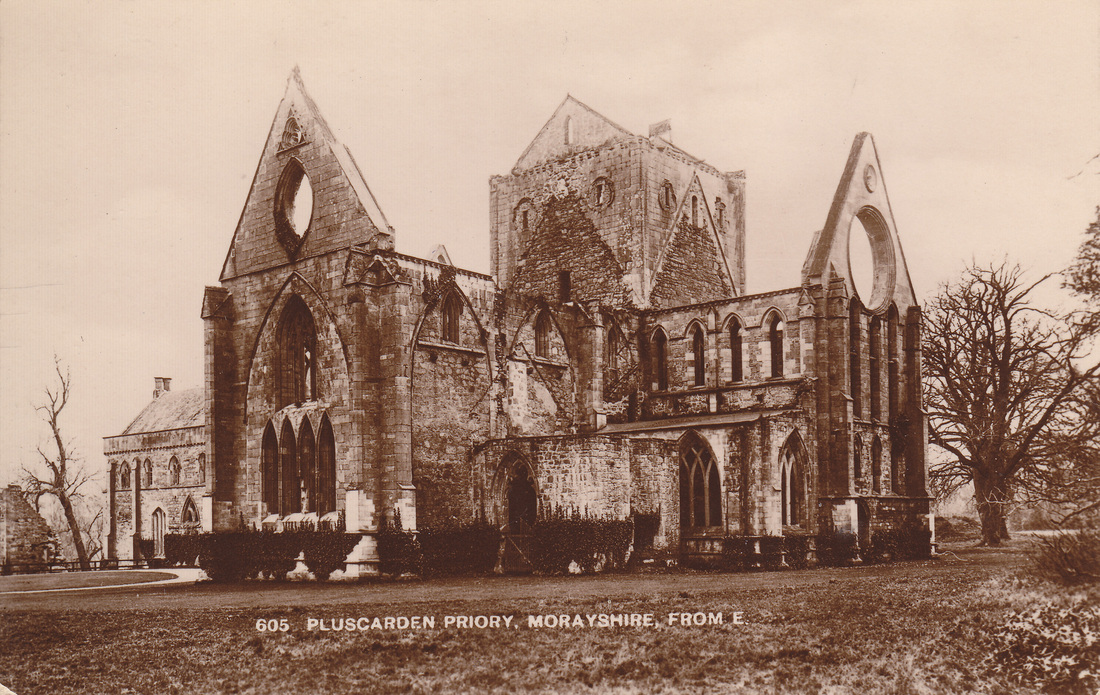

Pluscarden Priory from the SE. Postcard printed by Valentine & Sons Ltd

This picture has been taken from the SE, a short distance from the Elgin road, and uses a typical ‘picturesque’ technique of framing the view through foliage. Founded by photographer James Valentine in 1851, Valentine’s was probably the largest manufacturer of picture postcards in Britain by the end of the 19th century.

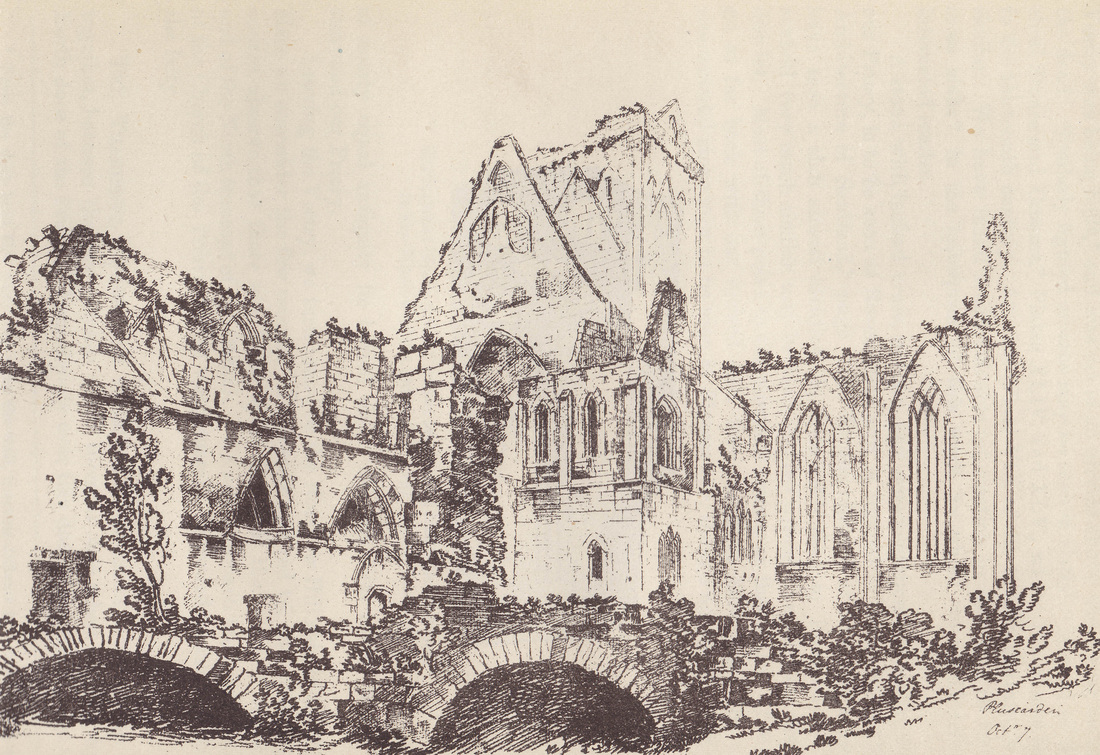

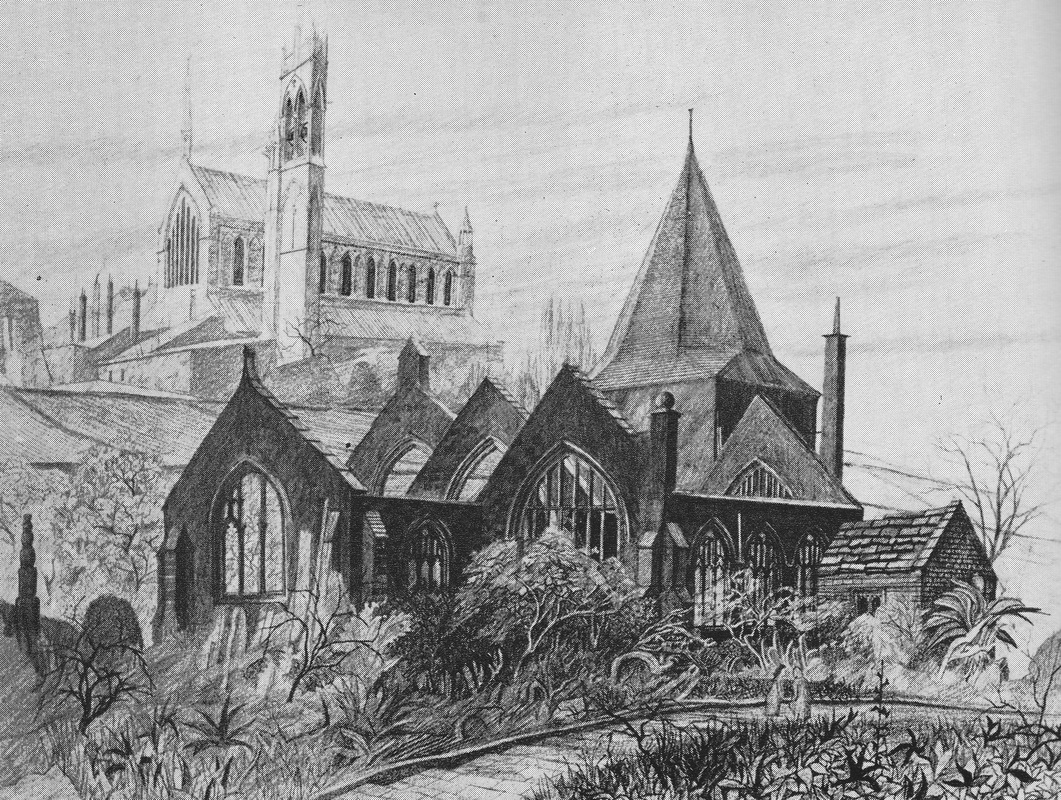

Pencil sketch of Pluscarden by Wilfrid Upson OSB, Abbot of Prinknash, in 1943, the year the priory was handed over to the monks of Prinknash Abbey

After the death of the Marquess of Bute, Pluscarden passed to his youngest son Lord Colum Crichton-Stuart. Ownership of the huge building was something of a burden – he was liable for the upkeep and had no wish to live there himself – and he was therefore keen to find a religious community who could take it over. Benedictine monks were the natural choice, as it was Benedictines who had lived here prior to the Reformation; he shared his father’s liking for ‘authenticity’.

Lord Colum visited Caldey in 1921 and made the offer to Abbot Aelred, who felt unable to accept. When Lord Colum repeated his offer in 1935, the community again declined. It was a case of third time lucky, as by 1943 Lord Colum had decided that if no monastic community was willing to take it on, he would have to hand Pluscarden over to the state. The above sketch was drawn in 1943, the year that Abbot Wilfrid finally agreed.

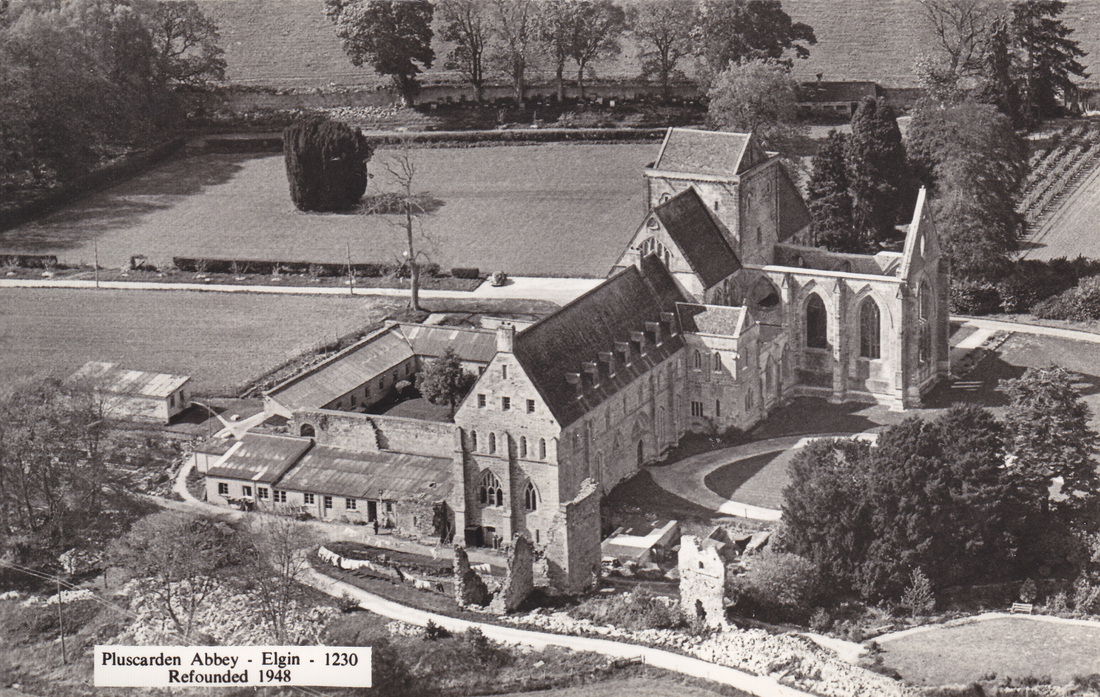

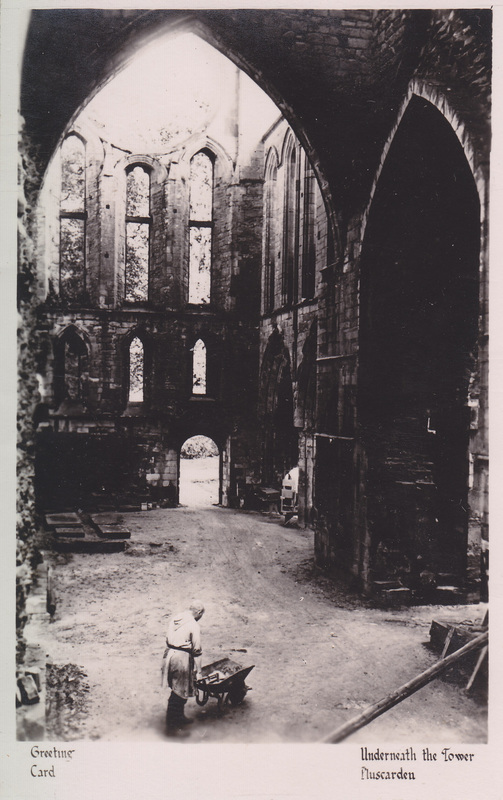

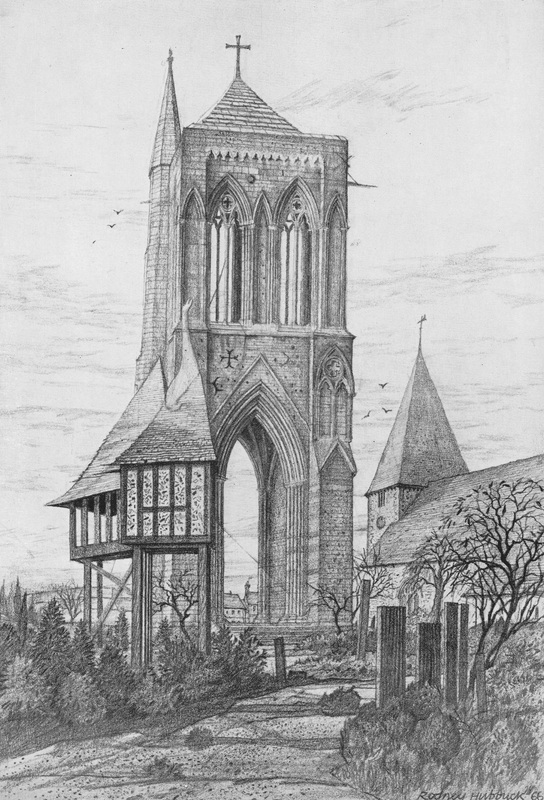

Practical moves had to be delayed until the end of the war, of course, but in 1945 arrangements began to be made. Architectural surveys were carried out, plans drawn up, historical research carried out. Five monks were sent in April 1948 to begin the work of restoration, and within four months the buildings were habitable enough to allow an official opening Mass on 8 September 1948.

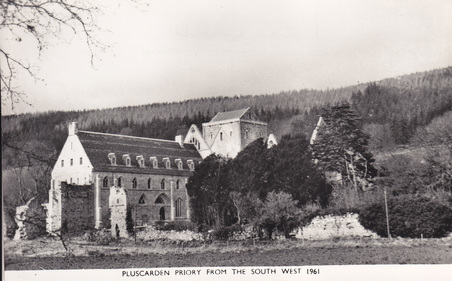

By 1961 restoration work had made considerable progress, and as the buildings became less ruinous, they begin to drift beyond the scope of this post. There will come a moment – at some distant point in the far future – when the structure will once again crumble and fall, and its ruinous state will be restored. But by that time I will have long ago laid down my pen.