Texts form an important part of the film. As part of their philosophy class Damien and Pierre are studying Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: a report on the banality of evil (1963); the Nazi’s defence that he was only ‘obeying orders’ is seen by them as a reflection of their own principle that in order for murder to be a crime, there must be a personal motive. Similar themes had of course already been considered in Dostoevsky’s 1866 novel Crime and Punishment.

The events depicted here are no philosophical fantasy however, but are rooted in historical fact. Adapted from Leslie Kaplan’s 2005 novel Fever, the story is inspired by the 1924 murder in Chicago of 14 year old Bobby Franks, which was carried out by two wealthy students, Nathaniel Leopold and Richard Loeb, in order to demonstrate their intellectual superiority. This crime provided the inspiration for the Rope (1929), by Patrick Hamilton (who also wrote Gaslight) – the play was adapted for the screen in 1948 by Alfred Hitchcock. Further layers of historical parallels are woven into the story as the boys grow increasingly anxious and paranoid in the wake of the crime, turning to their grandparents for reassurance while trying to exculpate themselves by reading up on France’s Vichy past. Narratives of personal and national guilt become intertwined with the students’ erratic behaviour. No-one is portrayed in isolation, and by exploring matters such as family dynamics and ancestral roots, the characters are fleshed out in a depth rarely found in contemporary crime thrillers.

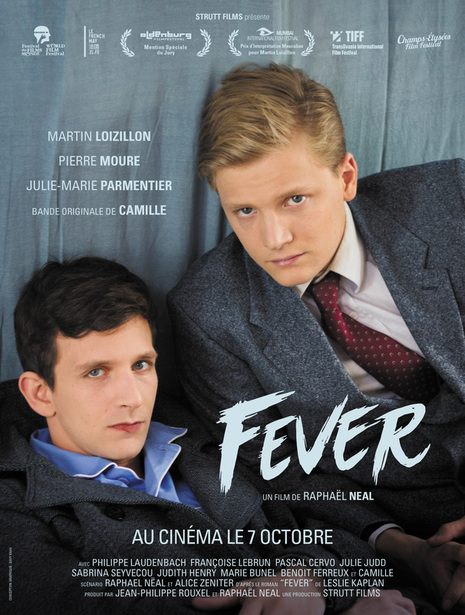

The nature of Zoé’s desire is not the only erotic element in the film. The relationships between the main characters are complex and ever-shifting, signified not only by the actors’ sensitive performances but also by a rich backdrop of visual and musical motifs. As I mentioned in a recent post on the noir film While the City Sleeps, unhealthy relationships with one’s mother often feature in movie portrayals of murderers, and there are strong hints here that Damien and his mother are rather more intimate than is appropriate. While there is also a definite homoerotic element in the relationship between Damien and Pierre, we see several shifts in their attitude to the women around them – such as their philosophy tutor Rosine, fellow students and Zoé herself. The alternation between desire, fear, misogynistic contempt and nervous embarrassment represents realistically the confused world of the adolescent. Many of these scenes take place with Peggy Lee’s 1958 hit ‘Fever’ playing in the background, various renditions of the song being performed by fictitious chanteuse ‘Alice Snow’ (actually the singer Camille) – including a striking concert sequence attended by Zoé and an equally memorable dance routine involving Damien and his mother.

Given Raphaël Neal’s background as a professional art photographer, the careful attention given to matters of lighting, pictorial composition and visual iconography is no surprise. As well as allusions to other films – the close-ups of feet descending a spiral staircase recalls Moira Shearer’s frenetic descent in The Red Shoes – there are nods to the work of Irina Ionesco, Peter Weir and Catherine Breillat, amongst others. This is a film that will reveal further riches with repeated viewing. The effective use of outside locations around Montparnasse, including the vast cemetery, provide a lively sense of edgy authenticity. Since making his screen debut as an actor in 2001 Neal has worked with the likes of Claire Denis, Claude Chabrol, Alexander Sokurov and Sofia Coppola, and opportunities to observe these great directors at work have clearly not been wasted. His debut as a director suggests he may have an equally distinguished career ahead.