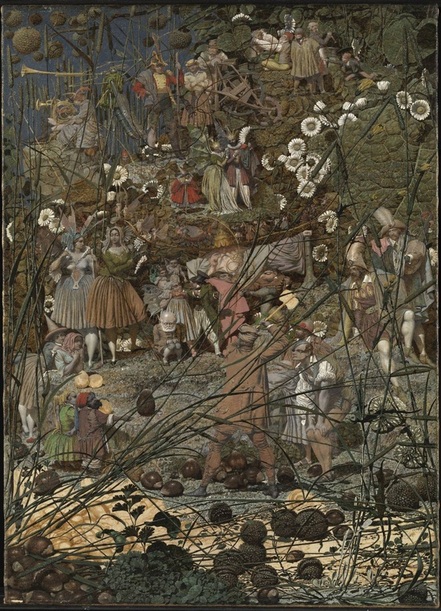

At Barnstaple pannier market a while ago I came across this old framed print and – after circling the stall several times – succumbed to temptation. The illustration is taken from the book In Fairyland: A Series of Pictures from the Elf World (London: Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer, 1870) and was the work of Punch illustrator Richard Doyle (1824-83.)

The artist was of one of the seven children of political cartoonist John Doyle (1797-1868), whose artistic skill was inherited by his four sons Richard, James, Henry and Charles (father of Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.) Of the four, Richard Doyle had the most successful career, and his early talent found him a place on the staff of Punch magazine when he was only nineteen. It was he who devised the famous image of the Punch cartoon character that adorned the magazine’s front cover from January 1849 until October 1956, replacing his earlier cover (January 1844) that featured crowds of elves and fairies.

Doyle’s talent for fairy drawings was first made public in 1846 with his artwork for The Fairy Ring (a new translation of Grimm’s tales), followed in 1849 by his illustrations for Fairy Tales from All Nations and Punch editor Mark Lemon’s The Enchanted Doll. He clearly relished the subject matter, and his skill in depicting pixies, elves, fairies and other fantastical creatures attracted commissions for a series of other fantasy titles such as The Story of Jack and the Giants (1850), and John Ruskin’s The King of the Golden River (1850), which went through three editions in its first year of public.

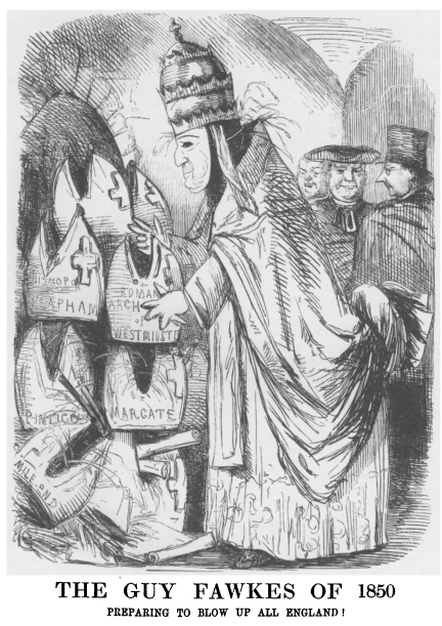

Another publication in 1850 had important consequences for Doyle’s career, however.

Doyle came from a devout Irish Catholic background and found himself increasingly unable to reconcile his faith with the magazine’s trenchant anti-Catholic stance. After the above cartoon appeared in November 1850, Doyle resigned from Punch. Over the next few years he undertook book illustration work for Thackeray and Dickens, before finding a new sense of purpose when he returned to his fairy artwork in the late 1860s.

This was by no means unusual at a time when fairies inhabited nearly every nook and cranny of Victorian literary and artistic culture. Their popularity raises some intriguing questions for a society that saw strident advances in industrial technology, and seemed proud of the victory of scientific progress over naive superstition. One wonders if the colourful jewel-like fairy world offered a sense of hope, an antidote, or the possibility of escape, when set against the rapid expansion of sprawling, smoking cities and the loss of rural traditions. Great artists – including Royal Academicians – recorded their fantastical visions of fairy lore on huge canvases, with the same painstaking precision and technical virtuosity applied to serious landscapes and religious subjects.

Here is just a small selection:

Richard Dadd The Fairy-Feller’s Master Stroke

Richard Dadd The Fairy-Feller’s Master Stroke

The artist worked on this painting between 1855 and 1864 when he was transferred from Bethlem Hospital to Broadmoor.

It is to this tradition of Victorian fairy painting that Richard Doyle’s In Fairyland belongs. Although dated 1870 on the title page, it was actually published in time for Christmas 1869. The folio was richly bound in green cloth, cost over 30 shillings, and has been described as one of the finest examples of Victorian book production. There are 16 colour plates – of which this my picture is the last – and 36 line drawings. Doyle was given free rein to design his own illustrations, which were later re-used in Andrew Lang’s The Princess Nobody (1884.)

Each plate was accompanied by a verse written by Irish poet William Allingham (1824-89), whose wife Helen was a skilled watercolourist and illustrator. That for Plate XVI reads:

Asleep in the moonlight. The dancing Elves have all gone to rest; the King and Queen are evidently friends again, and, let us hope, lived happily ever afterwards.

I have hung the picture on my study wall, between an oil painting of my childhood home and a line drawing of the cottage in which I now live. It seemed an apt place for the fairies to sleep.