Caroline: No. I’m the only one.

A Dandy in Aspic marked a turning point in Mia Farrow’s career, for although her name was widely known through her role (1964-66) as Allison Mackenzie in US soap opera Peyton Place, this 1968 spy film was her first major screen role and within months, she had followed it up with the starring role in Rosemary’s Baby. However, the film merits a closer look for many reasons, not the east of which is the magnificent array of fine couture on display.

The film’s production and Mia’s career

Mia left Peyton Place abruptly in order to marry Frank Sinatra in July 1966, after which it soon became clear to her that he was not happy with her pursuing a full-time film career. However, it was soon equally clear to Sinatra that his young wife had a mind of her own and was not afraid to stand up to him. Eventually a compromise was reached, and it was agreed that she could appear in one film a year. When casting for A Dandy in Aspic took place in January 1967 it seemed ideal: the schedule would involve Mia in ten days filming in London followed by three days in Berlin, so the couple wouldn’t be apart for long. Also, her co-star would be Laurence Harvey, who had been a friend of Sinatra’s since they worked together in The Manchurian Candidate (Frankenheimer, 1962). She said her goodbyes, and left Los Angeles for London in the middle of February.

As a matter of fact, Mia had not been the first choice for the character of Caroline: the part was offered to Julie Christie, who turned it down. She had already worked with the two males stars, having played opposite Laurence Harvey in Darling (1965) and Tom Courtenay in Billy Liar (1963), films that positioned her as the incarnation of the ‘Swinging Sixties’ girl. However, Dandy in Aspic would have been a very different film had she accepted the role. Christie’s sultry intensity was not what the film needed: Mia was an inspired choice.

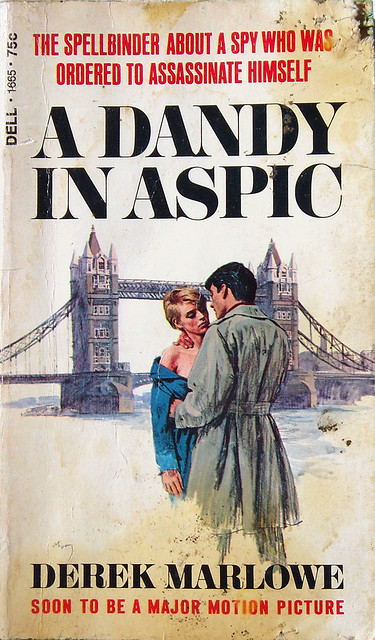

A Dandy for Aspic is a cold war thriller, adapted by Derek Marlowe from his own 1966 novel of the same name. Harvey plays Alexander Eberlin, a.k.a. Krasnevin, a Russian double agent working for the British intelligence service. Homesick and weary, he wishes to return to Russia but finds himself in a desperate position after he is despatched to Berlin – to track down and catch Krasnevin. His British colleagues include the imposing intelligence chief Fraser (Harry Andrews, from Saint Joan), his partner for the Berlin trip, Gatiss (Tom Courtenay) – who is openly hostile towards Eberlin from the first moment they meet – and the suave and lecherous Prentiss (played with relish by Peter Cook). Unfortunately Eberlin’s KGB bosses aren’t any friendlier, making it clear that they have no use for him back in Russia and the door to the east is closed…

As this brief synopsis indicates, this is very much a man’s world, bleak, dour and humourless, populated by men whose duplicitous lives have made them cold and cynical. Mia brought to the film not only a much-needed feminine presence in the character of Caroline, but also warmth, colour, humour and charm which would otherwise be conspicuous by its absence.

After her arrival in London, she flew out to Paris with Laurence Harvey where they were both fitted out with costumes by the legendary designer Pierre Cardin.

Although Harvey was already an experienced star with over forty films to his credit, the red carpet was rolled out for Mia, whose unique charisma and striking looks was already recognised: she was welcomed by the French ambassador’s wife, Madame Alphand, who Cardin deployed to deal with his most prestigious clients. As part of her contract, Mia was allowed to keep the Cardin outfits, some of which will be discussed below. After leaving Paris, Mia unexpectedly flew back to New York before travelling onto Miami where Sinatra was performing at the Fontainebleu Hotel. However she soon rejoined director Anthony Mann and the rest of the cast in London, and filming began.

Caroline Hetherington

Mia’s character, Caroline, is a London socialite and photographer, the daughter of Lady Hetherington, who first meets Eberlin at the Café Royale in Regent Street. Clearly intrigued, she asks if he is married, and engineers a meeting in the lobby as he prepares to leave. While most of the diners are in formal evening wear and finery, Caroline stands out in a short, sleeveless floral dress, over which she later slips a white fur-lined cape. Eberlin’s lack of interest in her reverses when he realises he is being followed, and he accepts her invitation to return to her flat, which doubles as a photographic studio.

It should be noted that there is no reference to her being a photographer in Marlowe’s novel, and it seems likely that the decision to introduce this theme into the film was inspired by the recent Blow Up (Antonioni, 1966), in which David Hemmings played a fashion photographer in ‘Swinging’ London. Caroline’s neat studio and her references to portraits of writers and actors positions her among the same sort of glamorous circles as Hemmings’ character Thomas, who was clearly based on David Bailey. The photography theme is not tossed aside, as it provides the motive for Caroline’s journey to Berlin – where she bumps into Eberlin again, apparently by coincidence – and she continues to carry and use her camera throughout the film. For those who are interested, she uses a 1965 Nikon F camera, with a Nikkor-S 50mm f / 1.4 lens, and fitted with a Photomic T viewfinder.

Caroline asks if she can take a photograph of Eberlin who refuses, prompting her to admit that she already has one of him that she took when he was on holiday in Tunis. (In the book, she glimpsed him in Tripoli and there was no photograph.) He asks if he can have it for reasons of vanity, but then destroys it when he leaves, without – as we suspect Caroline wished – having spent the night. Their encounter raises some intriguing questions about their motives. Firstly, it is suggested that Eberlin felt no romantic attraction to Caroline and only accepted her invitation to get away from the intelligence agents who wished to speak to him, while his pretended interest in her photographs was only a ruse to destroy evidence that he was in Tunis, where he actually carried out the assassination of a British agent. (A futile act, given that a) Caroline almost certainly retained the negatives of her work and b) his colleagues were already aware that he was in Tunis.) Regarding Caroline, however, few viewers are likely to believe that her repeated meetings with Eberlin are coincidence – and she must be fairly adept at clandestine photography if she can take a close-up portrait of a spy without him noticing. Is she in fact deliberately stalking him as part of another operation? This is something that is left open throughout the film. Evidence suggests otherwise, but the romance that develops between them is always underpinned by a vague sense that at least one of them is pursuing a secret agenda.

Despite the bleakness at the heart of the story, Mann did not follow the well-trod path of other cinematographers who convey this coldness through draining their films of colour. Both in London and Berlin the locations positively pop with vibrant tones, acting as a counterpoint to Eberlin’s increasing ennui and exhaustion.

Caroline is (apparently) over in Berlin for a photo-shoot, and manages to bump into Eberlin several times in different places across the city. She is accompanied by her photographic assistant Nevil, played by a young Richard O’Sullivan, a former child actor who would soon gain fame in TV sitcoms such as Man About the House and Robin’s Nest.

She goes along willingly with Eberlin’s new identity of ‘George Dancer’ but falls foul of Gatiss, who disapproves of her being around and is determined to keep Eberlin focussed on his task of finding Krasnevin. The double agent’s sojourn in Berlin is a bizarre sequence of furtive meetings, violent murders and grim conversations alternating regularly with romantic encounters with Caroline, some of which border on the surreal. He leaves her in bed during the night to despatch another agent in the bathroom along the corridor, while on another occasion he wanders off and finds her dressed in a cloth cap and fisherman’s sweater, sitting in a tree by a lake. No explanation is given either for her outfit or her presence there.

One has the sense that Eberlin knows there is no way out, and finds solace in Caroline’s quirky and unpredictable behaviour. It is clear too that there are genuine affections on both sides, although by this time it seems unlikely that there will be a happy ending. In one telling scene, they are interrupted in bed by Gatiss, who forces Eberlin to leave before telling Caroline: ‘I do believe you two would have got on well together. You haven’t got a past, and he doesn’t have a future. None at all.’

Their final meeting takes place at the AVUS race track just outside Berlin – which was also used in Anton Walbrook’s film Allotria (1936). These scenes blend real footage of races with a specially-filmed crash that appears to have been caused deliberately – and which will have fatal consequences for one of the party.

Sadly, there was another fatality in Berlin, as director Anthony Mann died of a heart attack on 29th July 1967, midway through filming. When Mia and the others heard he had taken ill, they all raced up to his hotel room but it was too late. In her memoir What Falls Away (1997) Mia describes her reaction to seeing her first dead body. It was decided that Harvey would direct the rest of the film – he also oversaw the final edit – with some assistance from Mann’s widow. This was uncredited at the time, and it is hard to know exactly which parts were filmed by Mann and which were the work of Harvey.

Her pale pink outfit emphasises her air of vulnerability and innocence.

When Eberlin and Caroline part, there is sadness on both sides, although perhaps for different reasons. Some commentators have suggested that Harvey’s cold and emotionless performance presents Eberlin as someone who is unable to feel anything for anyone – obviously sentimentality being a drawback for those working in espionage. Yet to me there is a sense of sadness, not only over his fate but also because his short time with Caroline has revealed to him what he has lost – both in her and within himself. A Dandy in Aspic is a film about identity rather than espionage – about the struggle to find one’s real self and the dangers of not being true to who you are. As Caroline remarks when she first meets Eberlin: ‘I’d say you’re definitely a Gemini. You know, two people in one.’ The fact that both Mia and Harvey were dressed in Pierre Cardin creations marks them out as a pair, two halves, and sets them apart from their friends and colleagues – Eberlin’s sartorial elegance (such as polo necks and lined collars) distinguishing him from the regulation suits worn by the other British agents. But I also feel that Mia’s performance brings out particular qualities of Caroline – colour, warmth, spontaneity, humour, charm, candour and vulnerability – that represent the humanity that Eberlin has denied or repressed. He sees in her what he might have been, another life he might have had – by which time, of course, it is too late…

The end of Caroline and Eberlin’s relationship was a portent for the demise of her real-life marriage, with Sinatra’s increasing irritation about her extended absence fuelling his resentment about her decision to pursue an independent film career. As the production ran over schedule, he rang her on set every day to ask when she was returning to the States. Other film work was to follow, with Secret Ceremony also being filmed in 1967. Ira Levin’s bestselling novel Rosemary’s Baby was published on 12 March 1967 and Mia was offered the lead role in the production, filming of which began in Hollywood that autumn.

A Dandy in Aspic received its premiere at the Columbia Cinema (now the Curzon Soho) in Shaftesbury Avenue, London, on 4 April 1968. In Arthur Marwick’s book The Sixties (OUP, 1968) he draws a distinction between the colour and optimism of the ‘High Sixties’ and the increasing pessimism and radical fragmentation of the ‘Late Sixties.’ A Dandy in Aspic offers a perfect example of a film that occupies a transition point between these two, with Mia’s innocent sense of fun and vibrant fashion sense giving way to the world-weary despair and disorientation of Laurence Harvey’s identity crisis. This is a film that really deserves to be better known. It occupies an important part in Mia Farrow’s career, both in terms of her breakout role in a major film and for its formative role in establishing her as a style icon.

This was part of the Mia Farrow Blogathon hosted by Gabriela at Pale Writer. Check out the rest of the entries here!