What could be more distressing than the sudden and mysterious disappearance of a loved one or family member? Probably being confronted with evidence that they never existed, and having both one’s memory and sanity thrown into doubt. This has been the disturbing premise of a number of films, which I began thinking about last weekend while watching the latest addition to this series – Fractured (2019)– which had just been streamed on Netflix. In this film, Ray Monroe (Jack Worthington) takes his daughter Perry to hospital after they both fall on a building site, and sits in the waiting room while Peri and her mother go off to get a scan. After some hours pass and they do not reappear, his questions about their whereabouts are met with a mixture of confusion, sympathy and increasingly belligerent impatience from different staff members, as the sign-in register, CCTV footage and doctors’ statements all indicate he arrived alone. Is his head injury to blame? Or is there something more sinister going on?

Fractured is a well-executed and fairly enjoyable movie, although anyone attempting to push this scenario in a contemporary setting has to find a way around the ubiquity of mobile phones and surveillance cameras which can easily be produced to prove or disprove basic facts such as these. It is notable for a film apparently set in the present day that no-one is seen using a mobile phone, and the hospital is still using VHS tapes for their CCTV recording in the emergency waiting room. Barnsley Hospital in South Yorkshire, for example, has over 160 surveillance cameras monitoring almost every public area including car parks, entrances, corridors, treatment rooms, offices and wards, and you can be fairly certain that they’re not recording everything on tape! Such disappearance films are more likely to convince if they are either made or set in the past, which is largely true of those listed below:

Unheimliche Geschichten [Uncanny Tales] (Richard Oswald, 1919)

Unheimliche Geschichten [Uncanny Tales] is a German silent film in which five short tales are linked together by a framing story set in an antiquarian bookshop at midnight, in which the figures of Death, the Devil and the Harlot emerge from paintings to tell the stories – similar to the devices used in the great portmanteau films made by Amicus in the 1970s. The first story is based on Anselma Heine’s novel Die Erscheinung [The Apparition], published in Berlin in 1912, which lays out the basic template for most of the films discussed below.

A young couple, played by two great Weimar figures – Conrad Veidt and Anita Berber – arrive at a hotel and check in for the night. He leaves her to spend the evening with friends, returning late – and drunk – to find his hotel room empty with bare walls, but puts this down to his drunken disorientation and sleeps elsewhere. In the morning, however, the woman is nowhere to be seen and his enquiries at the reception are meant with the firm insistence that he arrived alone: which is confirmed by the hotel register. The staff all deny having seen the woman. Who is telling the truth, and if they are lying, what could their reason be?

Midnight Warning (Spencer Bennett, 1932)

A similar scenario forms the setting for this Pre-Code Hollywood film in which Bill Cornish (William Boyd) – a private investigator – arrives at a Chicago hotel, the Clarendon Arms, to see old friend Dr Walcott, who is mysteriously shot through the open window. The hotel management seem very cagey about discussing the matter – and why is there a human ear bone in the fireplace of Walcott’s room? The trail leads Cornish to the apartment of Erich and his fiancee Enid van Buren (Claudia Dell), who checked into the hotel with her brother Ralph two months earlier. The next morning Enid travelled to Salt Lake City to sign some papers relating to an estate she had inherited, but when she returned to the hotel the staff denied all knowledge of their stay, the hotel register is blank and the room is not as she remembers. Distressed and disorientated, Enid is taken to the ‘psychopathic ward’ of the local hospital – is she mad, or is there some truth in her story?

In comparison with the other films discussed below, Midnight Warning (aka Eyes of Mystery) is a very masculine tale, dominated by burly men standing around talking, and the casual misogyny of their attitudes is exemplified in the way that the unpleasant attempts at ‘gaslighting’ are brushed off at the end ‘for the greater good.’ Indeed, one feature that many of these films have in common is the ease with which a lone woman’s voice can be dismissed by powerful men as hysteria, over-imagination, a bump on the head or too many drinks. Sadly, this remains as true today as it did in the nineteenth century setting of the earlier films.

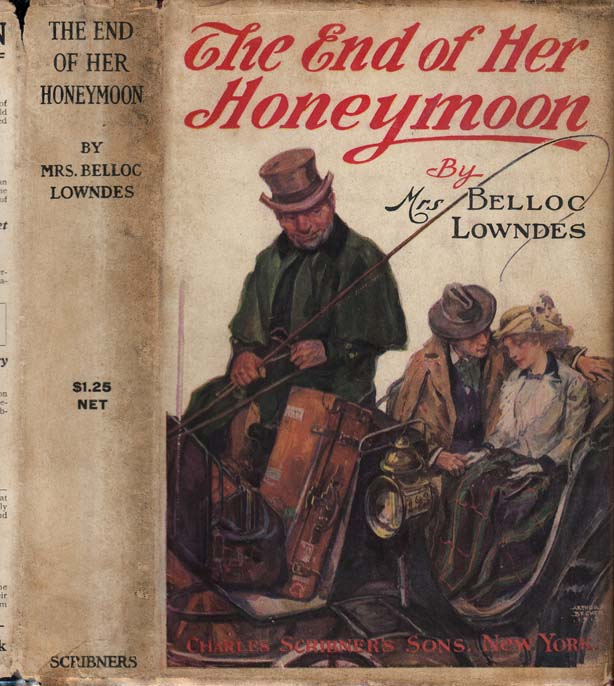

The story for Murder Mystery was written by Norman Battle but – like Unheimliche Geschichten above – it is based on the urban legend of ‘The Vanishing Lady’, also known as ‘The Vanishing Hotel Room’, which seems to have begun circulating in various forms in the late 19th century. It featured in Belloc Lowndes’ novel The End of Her Honeymoon (1913).

The Lady Vanishes (Alfred Hitchcock, 1938)

Probably the best known version of these stories is Hitchcock’s hugely popular mystery thriller, The Lady Vanishes, which won him an Oscar for Best Director. In this film Iris (Margaret Lockwood) tries to convince fellow traveller Gilbert (Michael Redgrave in his screen debut) of the existence of an elderly woman Miss Froy (May Whitty) who has vanished from the train as they journey through Nazi Germany. No-one believes her, and the only piece of evidence that she was ever there – the trace of her name on the coach window – mysteriously disappears as they pass through a tunnel before Iris can show it to Gilbert – a typical Hitchcockian touch, but one that was retained in the 1979 remake starring Cybil Shepherd and Elliot Gould, which turns the tale into more of a screwball comedy. The BBC 2013 adaptation is perhaps more faithful to the original source material, Ethel White’s novel The Wheel Spins (1936), on which all these versions are based.

So Long at the Fair ( Terence Fisher, 1950)

The plot of So Long at the Fair is rather similar, although the reasons for the disappearance and subsequent cover-up are different, hearking back to the template used in Lowndes’ novel. This film was adapted from Anthony Thorne’s 1947 novel of the same name – the screenplay was co-written by Hugh Mills and Anthony Thorne – and tells the story of Johnny (David Tomlinson) and his sister Vicky (Jean Simmons, above) who have travelled to Paris for the World Fair of 1889. Overnight, Johnny disappears without a trace – to the extent that even his hotel room number is erased. Again, no-one believes the distraught girl until artist George Hathaway (Dirk Bogarde) is drawn into the mystery, and the two begin to investigate (falling in love as they do so.) Jean Simmons is as sweet and delightful as ever, and the film benefits from some wonderful period detail – just look at the costumes and hairstyles! – as well as a fine supporting cast that includes Felix Aylmer, Honor Blackman and Cathleen Nesbitt.

Into Thin Air (Don Medford, 1955) – Alfred Hitchcock Presents

Hitchcock returned to this theme again in 1955 for an early episode in the first run of the anthology series ‘Alfred Hitchcock Presents’. The script was written by Marian Cockerell, based on Thorne’s novel, although in this version British visitors to the 1889 Exposition Universelle Mrs. Winthrop (Mary Forbes) and her daughter Diana (played by Pat Hitchcock, the daughter of Alma and Alfred) check into a Paris hotel on their way home. After Mrs. Winthrop falls ill, hotel doctor (John Mylong) sends Diana to his home for medicine, but when she returns there is no trace of her mother and all the staff deny that she was ever there…. The only person who believes Diana is an Englishman from the embassy, Basil Farnham (played by the wonderful Geoffrey Toone).

Bunny Lake is Missing (Otto Preminger, 1965)

Uniquely among the films here, Bunny Lake is Missing is set in contemporary Britain, although it was based on Merriam Modell’s 1957 novel of the same name, which is set in New York. Preminger’s film moves the location to London, where American single mother Ann Lake (Carol Lynley) has recently settled after moving from New York. When she goes to collect her four year old daughter ‘Bunny’ from the local children’s nursery, the child is not there, and the supervisor has no recollection of seeing her. As the police begin to investigate, they discover that there is no ‘Bunny Lake’ on the register, no children’s clothes, photographs or toy at Ann’s house, and that ‘Bunny’ was the name of Ann’s childhood imaginary friend. Unsurprisingly, Ann’s claims seem hard to believe, and she finds herself – like several other distraught females in this post – sedated and taken away for psychiatric assessment.

But she is fortunate in having diligent detective Newhouse (Laurence Olivier) on the case, who persists in his investigations despite his scepticism about Ann’s story. Olivier is just one of numerous fine actors in the film, which is populated with an assortment of strange characters – an eccentric schoolmistress who claims to collect children’s nightmares (Martita Hunt) , a doll-repairer (Finlay Currie), Ann’s brother Steven (Keir Dullea) and her lasvicious landlord Horatio (Noel Coward), not to mention Anna Massey, Adrienne Corri and Lucie Mannheim.

The Forgotten (Joseph Ruben, 2004)

This film differs a little from the others in that it contains a strong science fiction element, but the same basic strands are all here – the lone woman whose insistence that her child has disappeared is denied by friends and colleagues, leading to her being treated by a psychiatrist: only for the ‘conspiracy’ to fall apart and for the victim to be vindicated – although the film offers further twists after this. It’s all rather far-fetched, but worth watching for Julianne Moore’s performance as Telly Paretta, who is convinced that her son died in a plane crash – despite the denials by her husband and best friend – and the absence of any physical evidence – that she ever had a son. While her psychiatrist continues to treat her for what he sees as an obsessive delusion, she finds support from another man (Dominic West) experiencing the same thing with regard to his daughter. What is going on?

Flightplan (Schwentke, 2005)

Following the recent death of her husband David, an aviation engineer, Kyle Pratt (Jodie Foster) is travelling on a plane from Berlin to New York with her daughter Julia (Marlene Lawston) and David’s body in the hold. After she dozes off during the flight, she wakes to find that her daughter is no longer in her seat. Other passenger deny having seen her daughter – unsurprising perhaps, given the size of the plane and many of them sleeping during the night flight. But when the flight attendants try and persuade Kyle that she was travelling alone, the passenger manifest has no record of Julia, and a doctor in Berlin informs the captain that Kyle lost both her husband and daughter in an accident, the young widow begins to question her sanity….but could there be another explanation?

Following the same pattern as the earlier films mentioned above, with one explicit borrowing from The Lady Vanishes, Flightplan begins well as the suspense builds up and Jodie Foster – like Julianne Moore – puts in a convincing performance as a mother struggling to balance her maternal instincts and memories against the overwhelming weight of contradictory evidence. As the film progresses, however, the elaborate plot strains credibility somewhat, but the confined space of the plane makes Flightplan even more claustrophobic and tense than the hotel and train settings of other adaptations of the story.

The Changeling (Eastwood, 2008)

Although the premise is slightly different, there is a case for at least mentioning Clint Eastwood’s film The Changeling (2008) which starred Angeline Jolie and John Malkovich. Following the disappearance in Los Angeles in 1928 of Walter, the nine year old son of single mother Christine Collins (Angeline Jolie), the LA police carry out an investigation and claim to have found him. At the public reunion laid on to generate much-needed positive publicity for the corrupt and inefficient police force, Collins realises that the boy being returned to her is not Walter. The more she protests, the more evidence is produced to disprove her claims, leading to doubts about her sanity and fitness to look after her son. Although she is incarcerated in a state hospital for assessment, her case is taken up by a pastor (John Malkovich) and gradually the truth is revealed. The film is based on real events that took place in California in 1928.

As mentioned at the start, various versions of this story were published in newspapers and journals towards the end of the nineteenth century and those interested in exploring these should read here: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2010/09/14/vanishing-lady/

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window