‘They us’d to keep her out o’house, ’tis true,

A-nailen up at door a hoss’s shoe.’

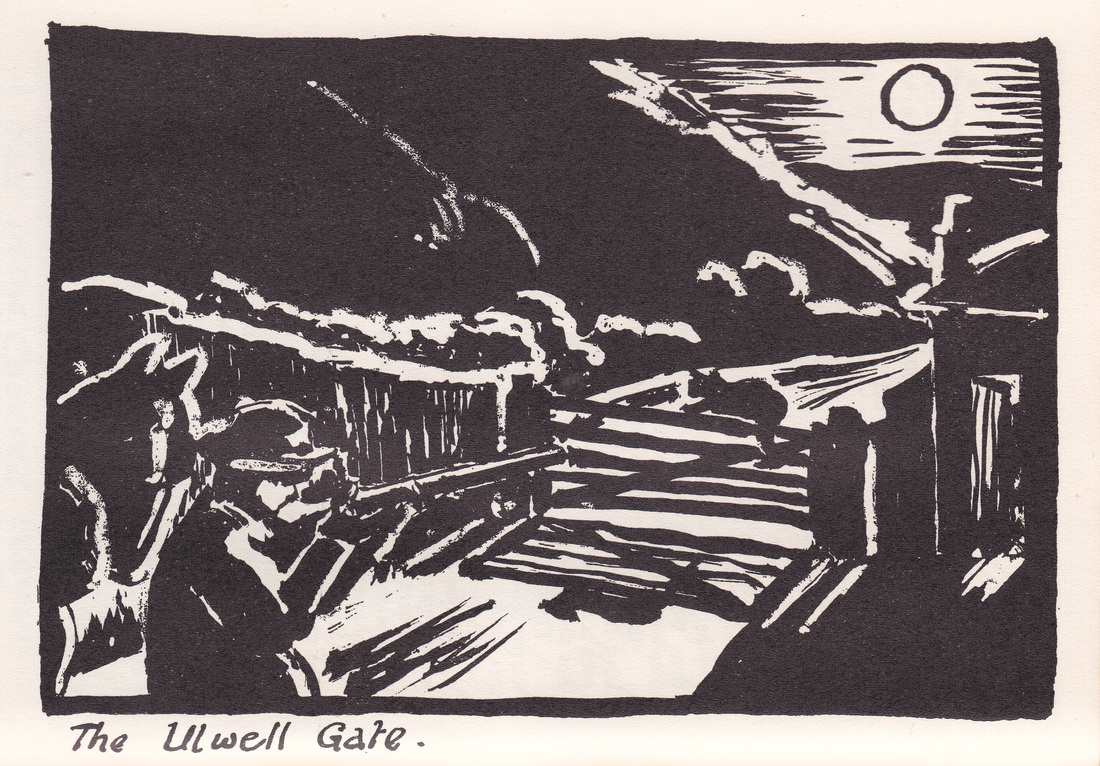

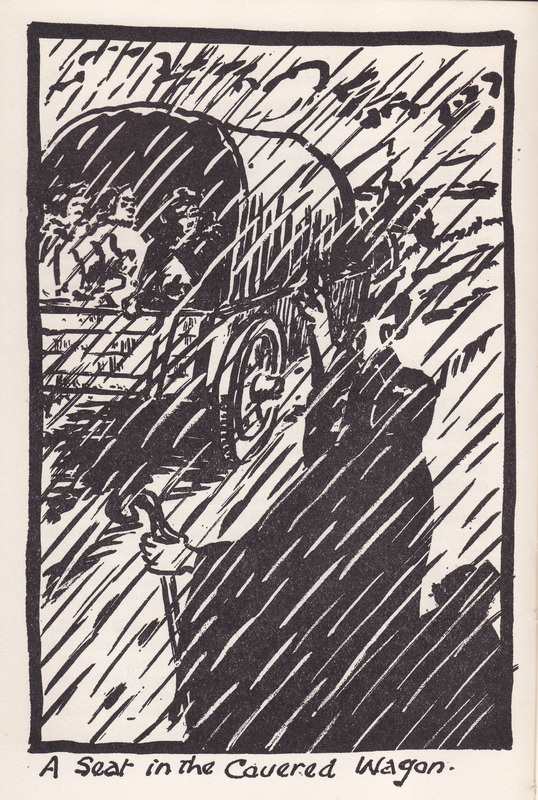

A picture of two linked horse-shoes is the first of about ten woodcuts by Kenneth L.G. Hart, who also illustrated her Old Dorset, Down Dorset Way, Tales of Dorset and More About Dorset.

Thomas Hardy lived in the same village as Olive Knott for about eighteen months (July 1876 to March 1878) and it was here that he wrote The Return of the Native (1878), which of all his novels is the one most concerned with local folk magic. One character, Susan Nunsuch, creates a poppet doll of Eustacia Vye, who is using her own unearthly powers to attract a local innkeeper whom she seeks to marry, but who is already engaged to another woman. Eustacia is described as having ‘pagan eyes, full of nocturnal mysteries’ and she is regarded as a witch by many of the locals. Both Susan and Eustacia are shown carrying out magic rituals, and it is interesting that ten years later, in his short story The Withered Arm (1888), the use of such rituals is again part of the conflict between two women, Rhoda and Gertrude, who are competing for the same man.

Hardy was on record as stating that these incidents were based on real events, and the wise man whom the two women approach for help – Conjuror Trendle – was a thinly disguised version of a local character still living at the time. Hardy’s friend Hermann Lea wrote about this, and many other supernatural incidents known to him, in his contribution ‘Some Dorset Superstitions’ to Memorials of Old Dorset (1907.)

Some of these traditions persisted for another thirty years at least. In The Return of the Native Susan also pricks Eustacia with a stocking needle in church, in the hope that drawing blood unseen would free her children from the spell that she believed Eustacia had placed on them. According to Olive Knott, a man in Charlton Marshall was cut on the hand in 1939 for the same reason, by someone who blamed him for ill-fortune.