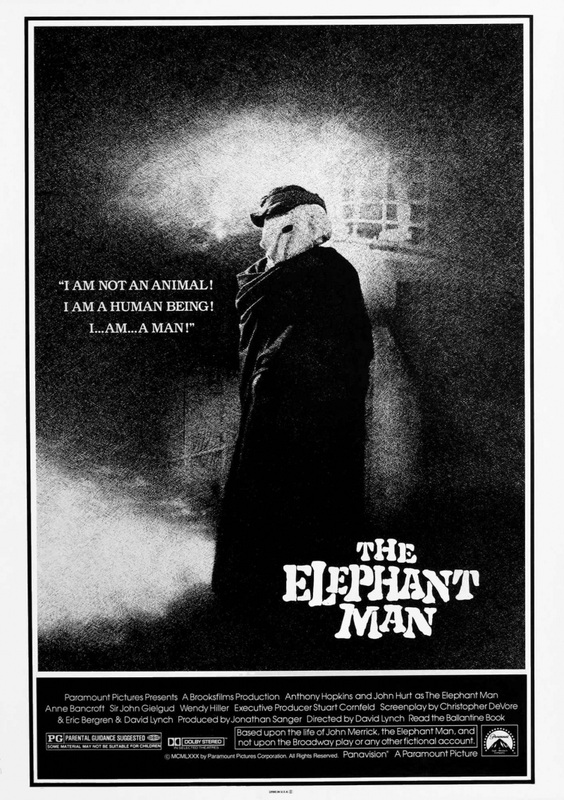

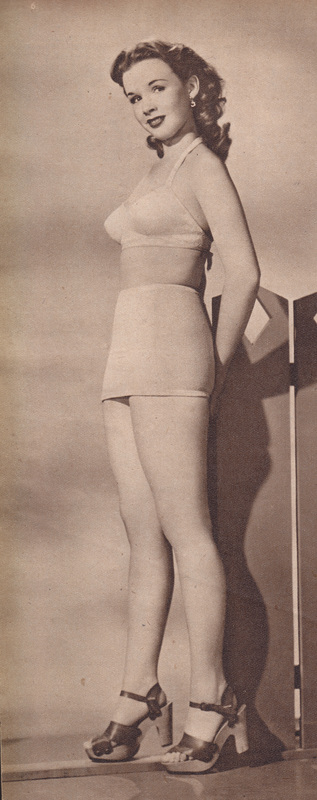

It is hard to equate the photograph below with the puritanical character of Margaret White in Carrie (Brian De Palma, 1976) with her negative opinions about ‘dirtypillows.’ Today’s blog post looks at the career of Piper Laurie, who was born in Detroit on this day in 1932.

Piper Laurie making her debut in Universal’s family comedy ‘Louisa’ (Alexander Hall, 1950) in which she played Ronald Reagan’s daughter

Born Rosetta Jacobs, she moved with her family to LA when she was six, and her acting career began with a few bit parts at Universal Studios, to whom she was eventually contracted in 1949. After the studio changed her name to Piper Laurie, she had her first big success with Louisa (Alexander Hall, 1951) in which she starred opposite Charles Coburn and Ronald Reagan.

Another Universal publicity photograph

Several other supporting roles followed in the early 1950s, including pairings with the likes of Rock Hudson and Tony Curtis, but dissatisfied with the work she was getting, Piper upped sticks and moved to New York. Here, she spent three years at drama school, developing greater depth as a character actress. Her experience and maturity was further boosted by appearing on stage and in live television dramas on Playhouse 90 and Studio One.

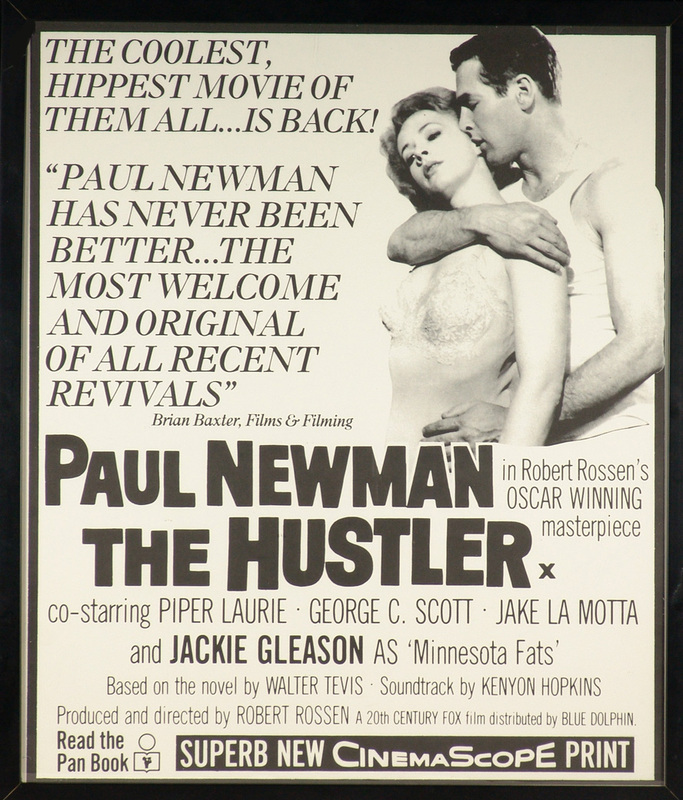

She was lured back to Hollywood to play Paul Newman’s depressed girlfriend Sarah Packard in The Hustler (Robert Rossen, 1961.) Her strong performance as the tragic alcoholic short-story writer – blending sadness, bitterness, fragility and a sense of desperate inner strength – earned her an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress – the first of three Academy Award nominations, none of which (to the everlasting disgrace of the panels) she would win.

As Sarah Packard in ‘The Hustler’ (1961)

Despite the critical success of The Hustler, Laurie stayed off the big screen for the next fifteen years, moving out to live in Woodstock with her husband – film critic Joe Morgenstern – and limiting herself to television and stage work while raising a family. She returned in 1976 with Brian de Palma’s Carrie, delivering another intensely theatrical performance that – as with Sarah Packard – gave much-needed depth and vulnerability to a character that could easily have been a two-dimensional caricature. She was nominated for an Oscar, but once again was unsuccessful, while Sissy Spacek – who played Carrie – went off with the award for Best Actress. The two actresses were reunited almost twenty years later in The Glass Harp (Charles Matthau, 1995), playing sisters Dolly and Verena Trumbo in Truman Capote’s gentle tale of small town life in the 1930s.

With Sissy Spacek in ‘Carrie’ (1976)

Unsurprisingly, offers to play maternal roles came in thick and fast after Carrie. Although some of these were for domineering or scary mothers, such the Agatha Christie mystery Appointment with Death (1988) and the giallo thriller Trauma (Dario Argento,1993), more serious work was also on offer: she got her third Oscar nomination for her performance as the mother of deaf girl Sarah Norman in Children of a Lesser God (Randa Haines, 1986.) As one might expect from a film about deafness, even though Laurie’s character can hear, she expresses an inordinate amount of meaning and emotion through subtle body language.

As Mrs Norman in ‘Children of a Lesser God’ (1986)

As the years flowed on, Laurie graduated to playing grandmothers in films such as The Dead Girl (Karen Moncreiff, 2006), Hounddog (Deborah Kampmeier, 2007) – both of which are rather too reminiscent of Margaret White repeat performances – and Hesher (Spencer Susser, 2010), as well as finding time to direct a short film, Property (2006)

Although the above survey gives some idea of the range of her talents, none of her performances was as bizarre as her role in the first two seasons of David Lynch’s television drama Twin Peaks. The first season was normal enough (relatively speaking of course – this was Twin Peaks), with her playing the part of Catherine Martell, the vengeful wife of Peter Martell (Jack Nance) who found the body of Laura Palmer. At the end of season one she disappeared in a blazing timber mill, and when the second season opened in September 1990 without Piper Laurie’s name on the credits, most people assumed her character had died and Laurie had left. However, in a characteristically Lynchian twist, kept secret from both the audience and cast, both were in fact present. On the set was an actor named Fumio Yamaguchi who spoke barely a word of English, and was playing the part of Japanese businessman Mr Tojamura. This was in fact Piper Laurie, dressed in a suit and disguised in heavy make-up including a black wig and moustache.

Twin Peaks will be back on the small screen in 2016, with stars including Kyle McLachlan and Sheryl Lee confirmed as returning for a new nine-episode series to be co-written and directed by David Lynch. There has been no mention of Piper Laurie returning, but then again – the same could be said of season two…

Many Happy Returns!