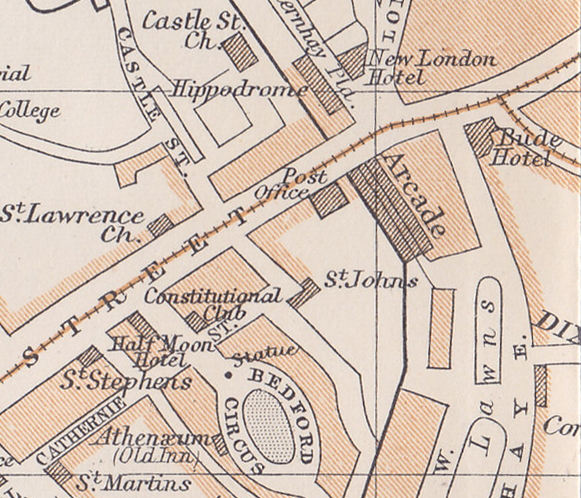

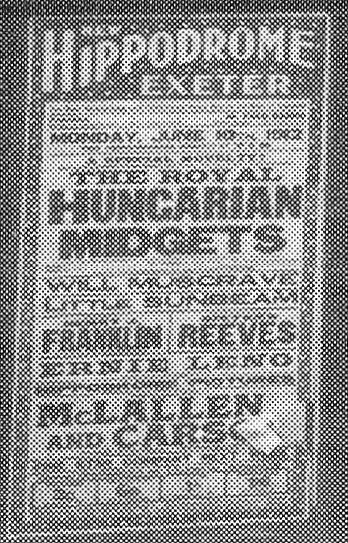

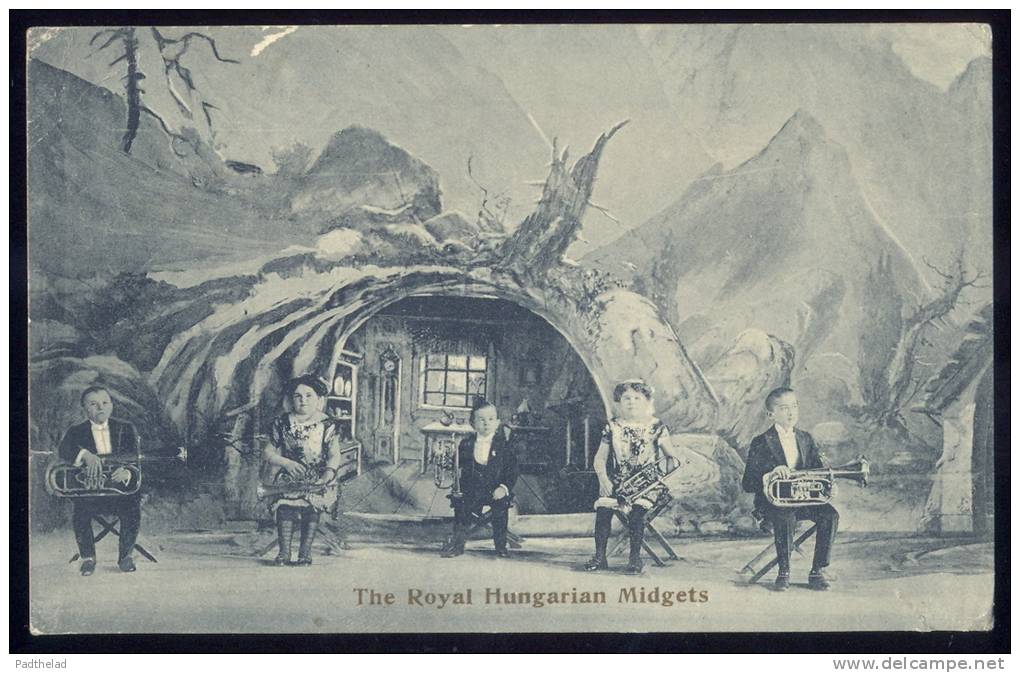

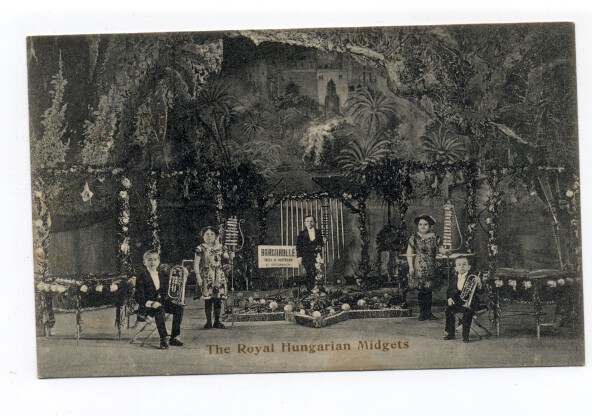

These two postcards show what one might have seen on stage in Exeter one hundred or so years ago. A contemporary playbill from America advertised:

A troupe of Royal Hungarian Midgets, headed by Prince Andru, the world’s smallest man…traveling with five other midgets, Prince Andru stands twenty-seven inches tall, weighs thirty-two pounds and is twenty-two years of age. The midgets perform in a beautiful well- lighted, airy miniature canopy erected on the show’s midway, presenting a high-class program of vaudeville acts with musical numbers.

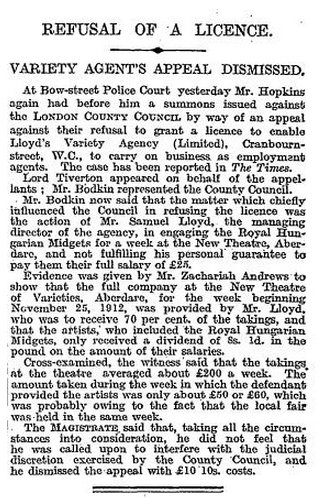

To modern sensibilities, there is something distasteful about the idea of exploiting physical irregularities, deformities or unusual features for commercial gain. Yet even if these performers were forced to market themselves using demeaning titles such as midgets, dwarves, living dolls, or bearded ladies, there is no denying that they were often able to attain a degree of financial security and social status that would have been denied them otherwise. Celebrity attractions such as Tom Thumb and Anita the Living Doll (interestingly, also said to be a native of Hungary), were introduced to the crowned heads of Europe and received visits and gifts from aristocracy, plus a weekly income far in excess of the average wage earned by their more able-bodied peers. Commenting on what they might have thought about their situation is a delicate matter, and it is difficult now in such an altered cultural and economic world to truly understand the nature of their relationship with both audiences and management. What is available in published writings and interviews typically formed part of a publicity campaign, and doesn’t really offer reliable insights into personal feelings and self-perception. On the other hand, there is concrete evidence that agents were sometimes guilty of – at the very least – financial mistreatment of the acts they represented, as this story from The Times illustrates:

The Hippodrome opened in 1908, which dates this poster to the four period between 1908 and 1912. Other acts that appeared there included Marie Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin, Ethel Bourne, Mona Garrick, Miss Mary Mayfren’s Company in The Yellow Fang (set in a San Francisco opium den), and ‘Consul’ the chimpanzee who performed in 1912 in top hat and roller blades – hence the phrase ‘variety’ entertainment! There is a distinction to be drawn, I think, between performers with musical or other talents, who happened to be of diminutive size – even if this was exploited as a novelty to gain attention – and the display of similar medical conditions in circuses and fairgrounds, where the physical features were the sole attraction of the act, and the performance consisted merely of being paraded in front of staring eyes. Such exhibitions continued in British fairgrounds right up until the 1970s, but would be found unacceptable now.

Public attitudes continue to change, and it is likely that performing animals – once inseparable from the image of a circus – will soon belong to the past. Today saw the second reading of the Wild Animals in Circuses Bill, which is being sponsored by Labour MP Jim Fitzpatrick. If passed, this will come into force in December 2015.

So, have we really moved on from a past age of cynical exploitation, when the misfortunes and sufferings of others provided a spectacle for public amusement? As I write this, I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here is screening on ITV and audiences gaze at malnourished non-entities immersing themselves in barrels of filth while eating live insects, a spectacle that would fitted in well with the Living Skeletons and rat-eating zulus of Victorian fairgrounds. Society’s treatment of those with disabilities and physical or mental illnesses may have moved on a little, but anyone who has experienced DWP assessments at the hands of ATOS will testify to fact that unseeing, unfeeling inhumanity and injustice remain very much a part of the present.