I’m posting this on the 119th anniversary of the birth of Adolf Wohlbrück, which took place in Vienna on 19 November 1896. Although born in the capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire, it is accurate to describe him as a German actor, given that his father was German and he lived for over thirty years in Germany before his emigration in 1936. Despite obtaining British nationality in 1947, the focus of Walbrook’s postwar career shifted increasingly towards Europe: much of his work in the 1950s and 1960s lay with studios and theatres in France and Germany. Today I’m going to write about an often-overlooked film, L’Affaire Maurizius (1954), which provided him with one of his darkest and most unusual roles. Although the film is based on a 1924 novel by German-Jewish author Jakob Wassermann (1873-1934), its themes resonated powerfully with the situation in post-war Europe when many people wanted to leave the past behind.

Told partly in flashback, the film opens with young Etzel (Jacques Chabassol), the sixteen- year old son of prosecutor Wolf Andergast (the great Charles Vanel), stumbling across an episode from his father’s past that would maybe best have been left buried. Andergast has no interest in revisiting the past, for he built his career upon the successful conviction of Léonard Maurizius (Daniel Gélin) for the murder of his wife Elisabeth (above.)

After talking to Léonard’s elderly father, however, Etzel learns that the guilty verdict was secured on the strength of the witness testimony of Grégoire Waremme (AW.) Pierre Paul Maurizius tells Etzel that his son had been a close friend of Grégoire’s since 1934, and this betrayal of friendship made no sense. Many people suspected there was a cover-up, but neither Andergast nor the court were interested in the truth. All they wanted was a successful conviction. It seems that Andergast’s career was built on a lie, and an innocent man has been condemned to life imprisonment.

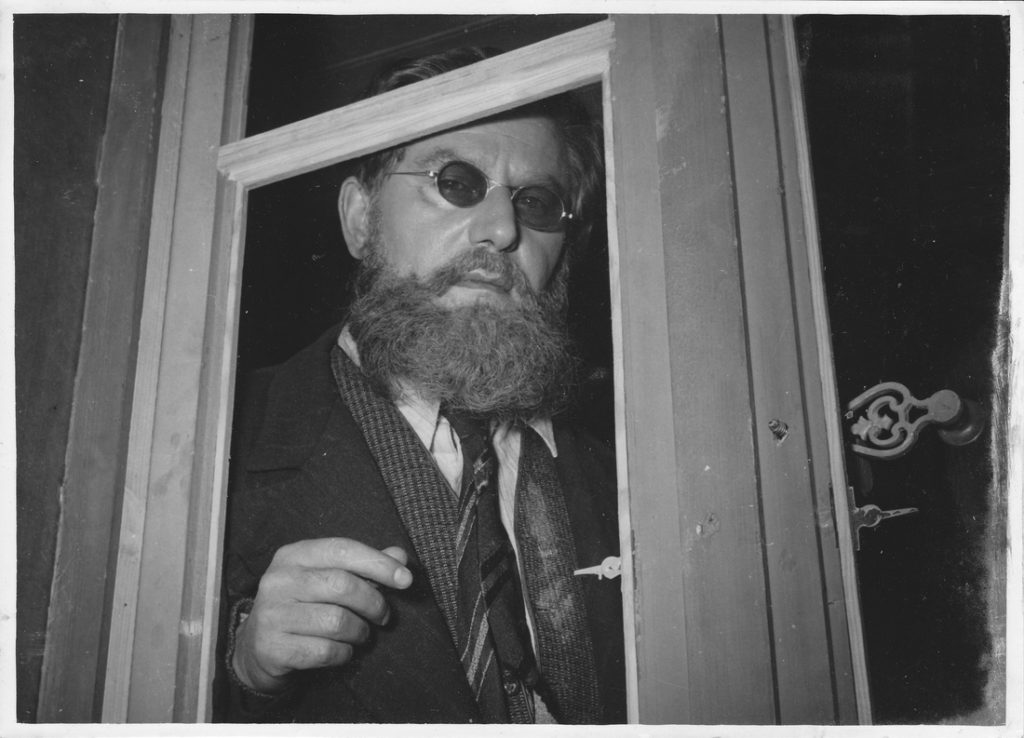

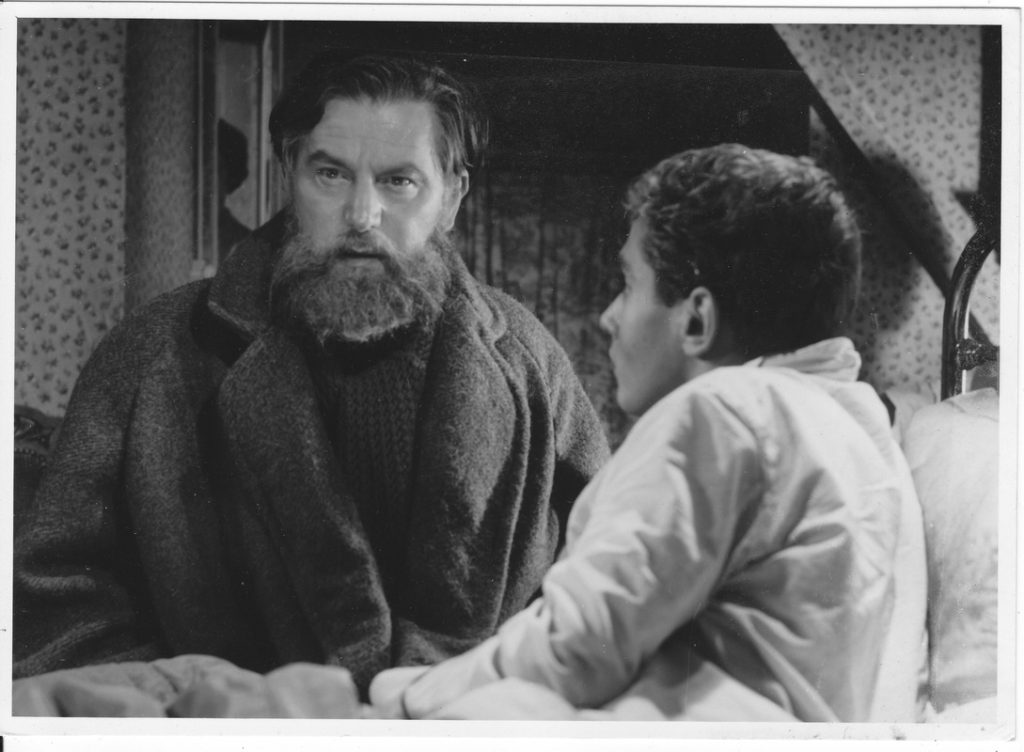

AW and Daniel Gélin during the filming of ‘L’Affaire Maurizius.’ The two men had worked together a few years earlier

in ‘La Ronde’ (Ophuls, 1950)

We are shown fragments of the past, learning about the complex three-way relationship between Maurizius and Elizabeth, a widow some years older than he, and her younger sister Anna (Eleonora Rossi Drago.) Events on the night of the murder are confused, but during the trial Waremme makes an impressive appearance in court. AW is, of course, a superb orator, as his monologues in Blimp and 49th Parallel demonstrate. Here he gives Waremme the voice of authority, speaking before the court with dignity, his face impassive. Waremme tells the court that he is an art critic, living in Bern but born in Vitebsk on 8 October 1900. This was of course just a few weeks before AW’s notional birthday – since the 1930s his year of birth was consistently given as 1900, suggesting that he was four years younger than he actually was.

My German poster for the movie

Meanwhile the idealistic young Etzel borrows money and sets out to discover the truth about the ‘the Maurizius affair.’ Waremme is now a professor of languages in Zurich, living in a boarding house – the Pension Bobike, 14 Augustinerstrasse. He has turned his back on the past, adopting the pseudonym of Professor Warshauer, and hiding his face beneath a beard and dark glasses. Etzel also adopts a new persona, finding an excuse to approach the professor by claiming to be a clerk named Edgar Mohl who needs English lessons before travelling to America. He wins the trust of Waremme, and discovers him to be a kind and gentle old man – further confusing the idea that he had given false witness out of some sinister motive.

Waremme is no fool, however, and his suspicions about Etzel’s identity are aroused when the young lad starts telling him about his desire to be a cowboy in America. Back in Bern, Wolf Andergast is shocked to hear that his son has set off in search of Waremme, and decides the time has come to make an unofficial prison visit to see Maurizius. Sooner or later, the truth must come out – but at what cost….?

It’s a bleak and pessimistic movie in many ways, and very different in tone from the film in which Duvivier had directed AW over two decades earlier, Die fünf verfluchten Gentlemen [the German language version of Les cinq gentlemen maudits] which was filmed in North Africa in the early summer of 1931. (See the photos with Camilla Horn here.) Apart from a few exterior shots in Bern, L’affaire Maurizius was filmed in a studios in Boulogne during the autumn and winter of 1953 – hence AW’s thick coats! As part of AW’s filmography it is often overlooked and underrated, undeservedly so in my opinion. Why not celebrate his birthday by wandering off the well-worn paths to explore Anton’s range and versatility as an actor?