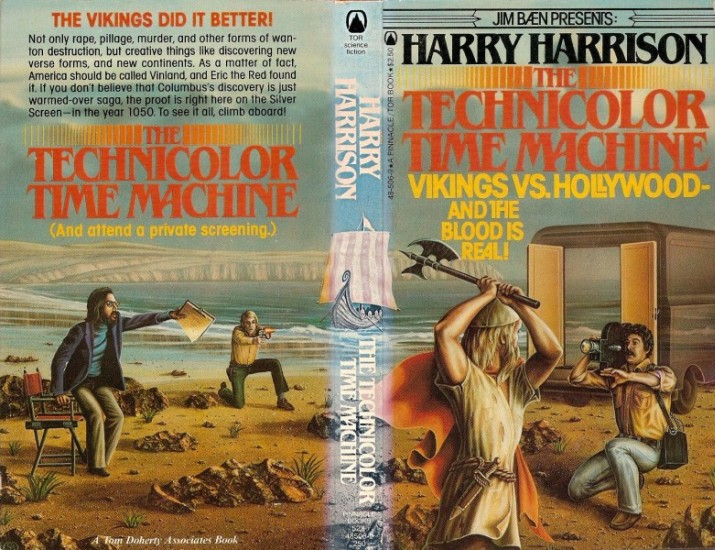

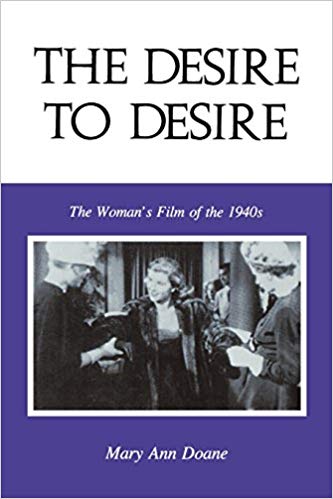

Anna Massey’s book takes a very different approach to that of Mary Ann Doane, although there is some overlap in their concern with how women engaged with the content of movies during the first half of the 20th century. Rather than using psychoanalytic theory as her starting point, Massey focuses on ‘edifices and artefacts…object-based material culture’ in order to explore the impact of American movies on British popular culture and design style. Her scope is far ranging, tracing the relationship between films and design by looking at the architecture of shops, cinemas and factories, interior room design, fashion, cigarette brands, advertisements, beauty products and family photographs. Unlike Doane’s work – which she cites – her writing is firmly rooted in real personal experiences, as is brought to life vividly by the inclusion of photographs of her mother and grandmother, with their own anecdotes about how their lives were affected by Hollywood movies.In her introduction to this book, entitled ‘Reclaiming the Personal and the Popular’, Anna Massey argues for the importance of embracing two strands that are often neglected in academic writing: a deliberate choice, spurred by the realisation that in much academic literature ‘affirmation of my own history and experience seems to be missing.’ (p.4)

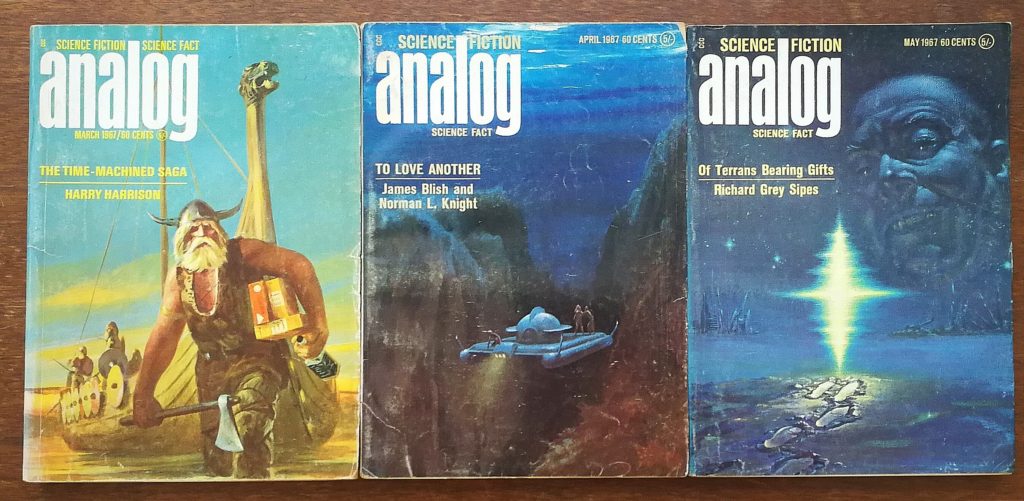

Joan Crawford and Dorothy Sebastian in Our Dancing Daughters (Beaumont, 1928)

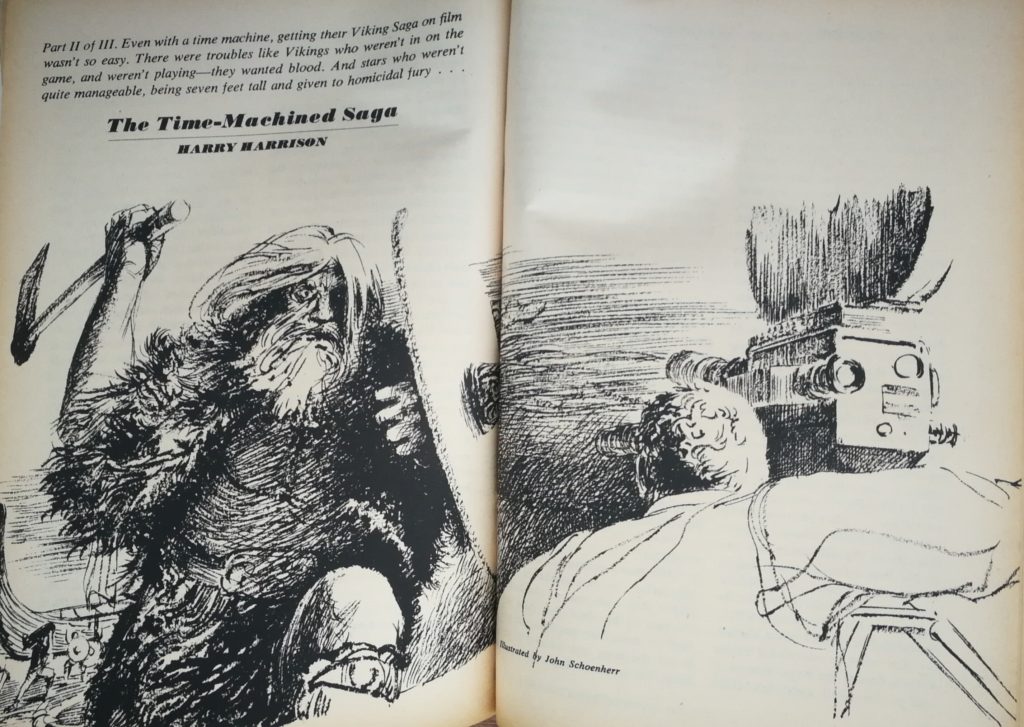

Using evidence drawn from these diverse sources and family anecdotes, Massey demonstrates the extent to which British popular and material culture was influenced at all levels by American style, as mediated through Hollywood, noting also how British intellectuals and establishment figures were determined to resist this Americanization which they associated with loose morals and subversive social mobility. There are four chapters, divided into rough chronological periods. The first of these, The Jazz Age, discusses developments between 1918 and 1929 when Hollywood eclipsed Paris in terms of influence on design, leading consumers in Britain to start looking towards America for the lead in matters of taste and style. A large chunk of this section looks at the films Our Dancing Daughters (Beaumont, 1928) and its sequel Our Modern Maidens (Conway, 1929) which propelled Joan Crawford to leading lady status and showcased Cedric Gibbons stunning art deco sets as well as Adrian’s daring costumes – which are discussed at length by Caroline Young’s book. Great concern was felt, both in America and Britain, about the dangers of young women trying to copy the behaviour exhibited in these films, and Massey quotes from women’s personal accounts of how they adopted the short skirts and flapper hairstyles worn on screen. A more specific expression of British resistance to Hollywood’s encroachment was the Cinematograph Film Act of 1927, although as the author makes clear, most of these attempts to hold back the American tide soon gave way in the face of popular and commercial demand – indicative of the tensions between elitist distaste for American culture and its mass popularity. In Chapter Two, Bright Style in Dark Days, – the largest section of the book – the author traces how art deco evolved into the more streamlined art moderne style and the impact this had on British culture during the early 1930s, particularly in the form of architectural design in the south of England. Films discussed include Grand Hotel (Goulding, 1932,) Dinner at Eight (Cukor, 1933) and Top Hat (Sandrich, 1935).

Joan Crawford’s home in Our Dancing Daughters

The third chapter on Cold War Cultures covers the period during and just after the Second World War, including the impact of Christian Dior’s ‘New Look’ fashion line launched in 1947, and postwar British resistance to American influence in the shape of British design fairs and the moral concern over the influence of rock ‘n’ roll, recalling how the film Rock Around the Clock (Sears, 1956) was banned by councils in Birmingham, Liverpool, Bristol and Belfast. She discusses Bette Davis in Now Voyager, the ‘Americanized left-bank glamour of Hepburn’ (p.160), Hollywood actresses’ endorsement of beauty products and the short-lived British magazine Film and Fashion. A concluding section, Post-modern glamour. A postscript, brings in some of the author’s own personal experiences of relating filmgoing to choices in dress and cultural attitudes, noting how the 1970s saw a revival of 1930s fashion, for instance through Mia Farrow’s stylish outfits in The Great Gatsby (Clayton, 1974).

The book should encourage readers to think more broadly about the cultural significance of classic films and the complex intersections that occur between the movies, avant-garde design, high fashion, popular culture and mass market commodities. The diverse and nuanced interplay between personal, popular, architectural and cinematic topics makes for a stimulating read, but it does create some problems for the author in trying to impose some order on the material and draw the various strands of her analysis together into a strong conclusion.

This will be the final post for the #ClassicFilmReading summer challenge this year, and for anyone who hasn’t done so, I’d recommend you check out the Out of the Past website for other reviews in the challenge as well as a wealth of material on all aspects of classic cinema

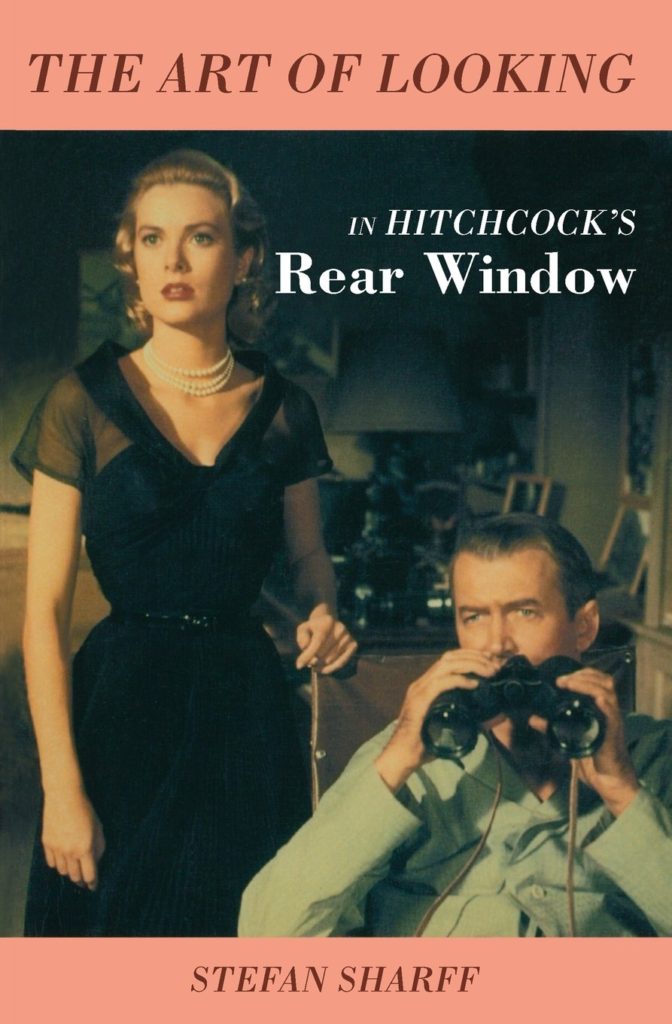

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window