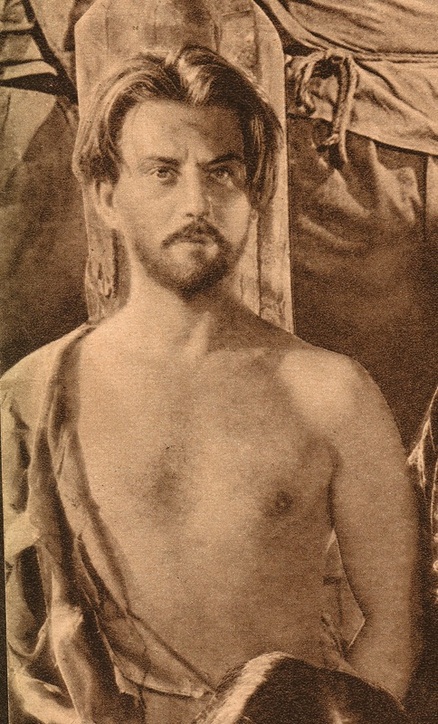

Today the Roman Catholic Church celebrates the feast of Saint Sebastian, an early Christian martyr who became the patron saint of athletes, soldiers, pin-makers and plague-sufferers. (The Eastern Orthodox Church keeps his feast on 18 December.) Today’s blog post therefore features an image of Anton Walbrook as Saint Sebastian.

Today the Roman Catholic Church celebrates the feast of Saint Sebastian, an early Christian martyr who became the patron saint of athletes, soldiers, pin-makers and plague-sufferers. (The Eastern Orthodox Church keeps his feast on 18 December.) Today’s blog post therefore features an image of Anton Walbrook as Saint Sebastian.

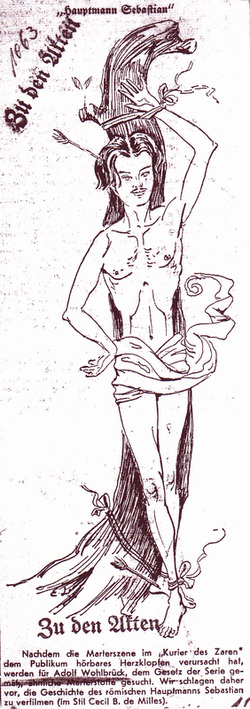

This image appeared in a German newspaper in 1936, responding to a scene in the film Der Kurier des Zaren which was released in Germany on 7 February. Adapted from Jules Verne’s 1876 novel Michael Strogoff, the film tells the tale of a Russian courier named Michael Strogoff who has to dash across Russia with a vital message for the tsar’s brother, wrestling with bears and fighting off ferocious Tatar rebels along the way. Captured by the Tatars, he is brought before their leader and blinded with a red hot sword by the executioner. It is this scene, depicting the actor in torn clothes and bared torso, lashed to a wooden pole, that evoked the comparison with ‘Captain Sebastian.’

So who was this saint?

According to legend, he was born in Narbonne in Gaul but brought up in Milan before travelling to Rome where he joined the army of the emperor Carinus. Sebastian was later promoted to captain of the Praetorian Guard under Diocletian, but the emperor condemned him to death because of his success in making Christian converts. He was taken out to a field where, according to the 14th century Golden Legend, ‘archers shot at him till he was as full of arrows as an urchin.’ Left for dead, he was found to be alive by a pious widow who came to bury him; she nursed him back to health, whereupon he returned to confront Diocletian and was promptly martyred a second time, being clubbed to death before his body was thrown into a sewer. This was around 288 AD. His remains were retrieved and reburied near the catacombs; the Basilica of San Sebastiano on the Appian Way became a site of medieval pilgrimage.

Sebastian’s story may seem to have little connection with the life of Walbrook, but the cartoon’s caption makes more sense if we unravel a little about the development of the saint’s iconography.

Examples can be found in John Addington Symonds’ Sketches in Italy (1883), Walter Pater’s short story Sebastian von Storck (1886), Anatole France’s satirical novel The Red Lily (1894), John Gray’s poem Saint Sebastian (1897) and Montague Summers’ Antinous and Other Poems (1907.) Oscar Wilde viewed Reni’s Saint Sebastian in Genoa in 1877 on his way to Rome, where he visited Keats’ grave and made a strong association between the two dead youths: in his poem The Grave of Keats he calls the poet ‘Fair as Sebastian, and as early slain.’ The title character of Wilde’s novella The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) wore a cloak studded with ‘medallions of many saints and martyrs, among whom was St. Sebastian’ and after Wilde’s release from prison he moved to France under the pseudonym of Sebastian Melmoth. Another of Reni’s Sebastian paintings inspired Frederick Rolfe to write ‘Two Sonnets for a Picture of Saint Sebastian the Martyr in the Capitoline Gallery, Rome’ which was published in The Artist magazine in June 1891. The same portrait had a profound effect on Japanese novelist Yukio Mishima, who – shortly before his death – had himself photographed as Saint Sebastian by Kishin Shinoyama. This was nothing new – Jean Reutlinger did the same in 1913 and models posing as Sebastian had been captured by the cameras of Victorian and Edwardian photographers from Oskar Rejlander (1867) to Frederick Holland Day (1905-7.) Even a cursory perusal of these writings and images reveals the extent to which Sebastian had become a homoerotic icon by the beginning of the century. Audiences – including tuned-in newspaper readers – knew what was being hinted at when an actor or artist was presented as another Saint Sebastian.

Like one lying down he stands there, all

Like one lying down he stands there, alltarget-proffered by his mighty will.Far-removed, like mothers when they still,

Self-inwoven like a coronal.And the arrows come, and, as if straight out of his own loins originating, cluster with their feathered ends vibrating.But he darkly smiles, inviolate.Only once his eyes show deep distress, Gazing in a painful nakedness; Then, as though ashamed of noticing, seem to let go with disdainfulness those destroyers of a lovely thing.

‘I have a favourite saint. I will tell you his name. It is Saint Sebastian, that youth at the stake, who, pierced by swords and arrows from all sides, smiles amidst his agony. Grace in suffering: that is the heroism symbolized by St. Sebastian. The image may be bold, but I am tempted to claim this heroism for the German mind and for German art, and to suppose that the international honour fallen to Germany’s literary achievement was given with this sublime heroism in mind. Through her poetry Germany has exhibited grace in suffering.’

‘I have a favourite saint. I will tell you his name. It is Saint Sebastian, that youth at the stake, who, pierced by swords and arrows from all sides, smiles amidst his agony. Grace in suffering: that is the heroism symbolized by St. Sebastian. The image may be bold, but I am tempted to claim this heroism for the German mind and for German art, and to suppose that the international honour fallen to Germany’s literary achievement was given with this sublime heroism in mind. Through her poetry Germany has exhibited grace in suffering.’

These words are from Thomas Mann’s speech in Stockholm on 10 December 1929, given at his acceptance of the Nobel Prize in Literature. The prize had been granted in recognition of novels such as Buddenbrooks (1901) and The Magic Mountain (1924) rather than the novella Death in Venice (1912), to which Mann appeared to allude in his acceptance speech. The following passage occurs in the second chapter of Death in Venice:

‘a keen essayist had remarked once: that he was the conception of “an intellectual and ephebe-like masculinity that stands silent in proud shame, clenching its teeth while it is pierced by swords and spears.” That was beautiful, intelligent, and correct, despite its somewhat exaggerated accentuation of passivity. Because grace under pressure is more than just suffering; it is an active achievement, a positive triumph and the figure of St Sebastian is its best symbol…’

The novella recounts the final days of a middle-aged writer, Gustav von Aschenbach, who has become obsessed with a beautiful young boy he has seen while on holiday in Venice. A year before Wohlbrück began filming Der Kurier des Zaren, his name arose in discussions about a film adaptation of Death in Venice. Mann had his doubts, however, feeling that Wohlbrück was zu schön (too handsome) for the lead role of Aschenbach. The character is actually in his early fifties and clearly past his prime; towards the end of the story, he resorts to make up to disguise his age. Wohlbrück at this time was only 37. The film was never made, and audiences had to wait until 1971 when Dirk Bogarde played the part at the more appropriate age of 49. The German newspaper’s suggestion [above] that Wohlbrück should appear in a film about Saint Sebastian, ‘made in the style of Cecil B De Mille,’ was not taken up either. The first, to my knowledge, was Derek Jarman’s Sebastiane (1976.)

Thomas Mann’s family were intimately involved in the theatrical and cinematic circles frequented by Adolf Wohlbrück. The film that made Marlene Dietrich a star, Der Blau Engel (1930), was based on the novel Professor Unrat by his brother Heinrich Mann. Thomas’s son Klaus Mann was engaged to actress Pamela Wedekind, while his daughter Erika was married to Gustaf Grundgens for three years. Klaus portrayed his brother-in-law in his 1936 novel Mephisto, criticising him for compromising with the Nazis. Grundgens’ marriage to Erika Mann was thought to have been a lavender marriage, as was his later marriage to Marianne Hopper. After they separated in 1929, Erika embarked on a series of lesbian affairs, beginning with Pamela Wedekind. She opened a cabaret in Munich, Die Pfeffermühle, where anti-Nazi sketches were performed. Pamela Wedekind later married Charles Regnier; their son Anatole referred to Wohlbrück in his memoirs.

The writings of Thomas and Heinrich Mann had been publicly burned by the Nazis in May 1933, and both authors had left the country before Wohlbrück’s name was suggested for Death in Venice. Although the Manns were joined in exile by a great many other writers, actors, directors and leading figures from the arts, for the time being Wohlbrück, Gründgens, Schünzel and others continued to work in Germany. The choice was not simply one of staying or leaving: remaining in Germany raised questions about how to live with the Nazi regime. One could endure for a while, emulate Saint Sebastian’s ‘grace under pressure’, but it was impossible to sustain the act for long. By the time Der Kurier des Zaren was released, Wohlbrück was looking for ways to leave Nazi Germany.

Pingback: Bear essentials – Dark Lane Creative