Mary of Scotland was Kate’s tenth film, but the first in which she attempted to play the part of a mature woman. Typically, the project was her initiative: her interest in playing Queen Mary arose after she saw the Broadway hit of the 1933/34 season, Maxwell Anderson’s blank verse play Mary of Scotland. On stage, Mary Stuart had been played by Helen Hayes, who followed this up with another critically-acclaimed regal performance in Victoria Regina – but portraying famous monarchs, either on stage or screen, poses some unique challenges, and the role differed somewhat from those previously tackled by Kate. True, she had done two period films, one of which – The Little Minister (1934) – was set in 19th century Scotland: but the character of Babbie shared the same feisty spirit of many other Hepburn heroines, caring little for the solemn shackles of historical accuracy. How would she respond to this challenge?

Mary, Queen of Scots (Kate) with her future husband, the swashbuckling, roguish James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell (Fredric March.) Family legend claimed that Kate was a direct descendant of the Earl; throughout the film he is referred to as ‘Bothwell’, and never ‘Hepburn.’

Films about royalty – like the actual monarchs themselves – need to find a fine balance between public office and private personality. In Mary of Scotland the rival queens both get the balance wrong: Mary is tempted to follow her personal feelings over her state duties – ‘What’s my throne?’ she tells Bothwell, ‘I’d put a torch to it for any one of the days I’ve had with you.’ In complete contrast, as Mary tells Throckmorton, ‘Elizabeth has never taken a single step that wasn’t political.’ The film grinds home the connection between Elizabeth’s preoccupation with power and statecraft and her status as the ‘Virgin Queen.’ While Elizabeth is continually surrounded by her courtiers and cabinet, frequently seated behind a writing desk or large table, we see Mary in domestic settings, small intimate gatherings that feature music, needlework and gentle banter with her ladies-in-waiting.

Such a dichotomy between a women’s sexuality and her career fits better with the outlook of the ‘Thirties than with contemporary views on gender equality, but the film’s portrayal of the two queens was shaped by a number of factors.

Kate originally wanted the film directed by George Cukor, who enjoyed a reputation as a ‘women’s director’ due to his nuanced work with strong female leads. He worked with Hepburn on eight films, including her debut A Bill of Divorcement, and also found success with stars such as Bergman, Garbo, Crawford and Holliday. The box-office failure of cross-dressing Sylvia Scarlett (1935) meant that RKO producer Pandro Berman refused to hire Cukor, signing instead John Ford, regarded as a ‘man’s director’ – his output of 140-odd films is dominated by male stars, with only a handful of decent female roles.

Unsurprisingly, Ford placed less emphasis on the romantic aspects of the story than he did on the film’s historical pageantry and atmospheric set designs. Mary and Bothwell’s relationship develops against a backdrop of fog-shrouded castles, the courtyards of which are teeming with soldiers and animals; there are torchlit processions, massed bands of pipes and drums, plus the inevitable clashing of claymores and rearing horses.

The queen did not remain aloof from all the action, and in one scene Kate had to run down a flight of stone steps in her heavy costume before mounting her horse and galloping off. She did the stunt herself, as she would continue to do until her early seventies, despite the danger of tripping over the cumbersome dress with its flowing train.

Her costumes had once again been designed by Walter Plunkett, who excelled at recreating period dress and worked closely with Kate during her RKO years. One of these, a dress of crimson silk, decorated with gold thistle emblems, was displayed at the V&A’s Hollywood Costumes exhibition (2012-2013.) Plunkett was not the only one to take period detail seriously. Before filming began, both Ford and Hepburn spent time researching Scottish history and reading up on Mary’s life and background. Kate rehearsed in private wearing Plunkett’s costumes, practising – for example – how to turn her head naturally wearing a high ruffs collar such as this.

Nonetheless, there are numerous anachronisms – not least in the musical settings – while the historical bias in Mary’s favour overlooks a number of dark deeds and murky motives, the blame for which cannot be entirely laid elsewhere. It was impossible for a Hollywood film – even at two hours – to convey the complex religious and political turmoil of 16th century Scotland, with the kaleidoscope of shifting allegiances amongst the Scottish Lords and the web of conspiracies, plots, counter-plots and forgeries in which Mary was embroiled all her life. In consequence, her romance with Bothwell is pushed to the forefront, and that in turn required that his character be whitewashed: their possible involvement in Darnley’s murder is represented only as a wild accusation from the mouth of firebrand Protestant preacher John Knox.

Moroni Olsen, who gave a dramatic performance as Knox, was the only member of the original Broadway cast to appear in the screen adaptation.

Moroni Olsen, who gave a dramatic performance as Knox, was the only member of the original Broadway cast to appear in the screen adaptation.

The screenwriter Dudley Nichols – a regular collaborator with Ford – did away with Maxwell Anderson’s blank verse, but his screenplay retains much of the speechifying and dramatic monologues that betray its stage origins. Kate did her best with the stilted, over-expository dialogue, but neither Ford’s direction nor Nichols’ script really allowed her enough space to develop Mary’s character. Frustration about this led to a disagreement during filming on the 10th April, when they were due to shoot the intimate scenes between Mary and Bothwell on the ramparts of Dunbar Castle, the night before their final separation. Ford wanted to drop the scenes as an unnecessary piece of soppiness, while Kate regarded them as central to the film’s depiction of the relationship. After a heated exchange, Ford handed her the script and megaphone, walked off the set and told her to direct the scene herself if she thought it so important. She did, and the film is better for it.

Ford’s direction of Hepburn reveals the strong feelings he had for her: there are a disproportionate number of close-ups, the camera lingering upon her face with an attentiveness granted to no-one else in the cast. Few films captured Katharine’s beauty so well. The luminosity of Joe August’s cinematography, combined with the close-up editing of Jane Loring, made the footage of Kate fit perfectly with Elizabeth’s comment on Mary, in Anderson’s play, that not since Helen of Troy:

has a woman’s face

Stirred such a confluence of air and waters

To beat against the bastions. I’d thought you taller,

But truly, since that Helen, I think there’s been

No queen so fair to look on.

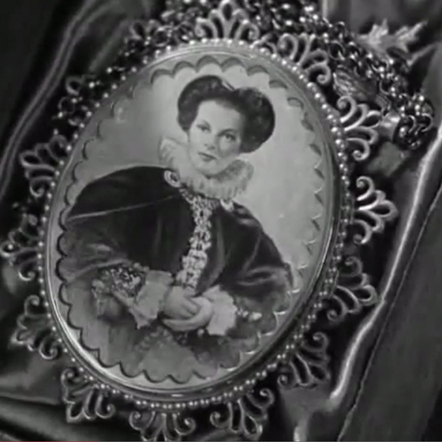

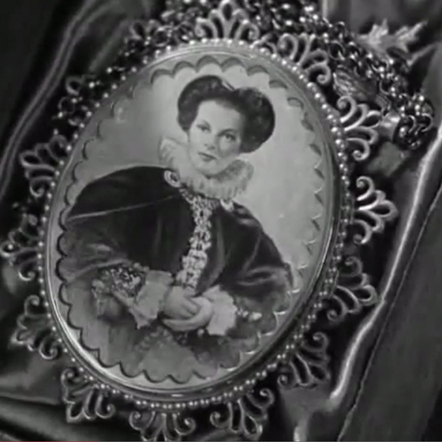

A miniature shown to Queen Elizabeth as an indication of her cousin’s youthful beauty. Not a bad likeness of Katharine Hepburn either.

A miniature shown to Queen Elizabeth as an indication of her cousin’s youthful beauty. Not a bad likeness of Katharine Hepburn either.

Filming was completed on 25 April 1936 and Mary of Scotland was released on the 28 August. Three days later the New York Times praised the picture’s ‘depth, vigor and warm humanity’, but admitted dissatisfaction with Hepburn’s portrayal of Mary. The moments when the Scottish queen was ‘womanly, tender, impetuous and of high courage’ were convincing, but – while Anderson’s play showed Mary’s vengeful and ruthless side – the film script had tried to soften this and thereby introduced inconsistencies to her character.

It was only towards the end of the film, when Mary was imprisoned and put on trial, that this forcefulness began to burn through and Kate’s performance took on new vigour.

Mary’s cousin Queen Elizabeth (left) was played by March’s wife, Florence Eldridge, although the part was sought by both Ginger Rogers and Bette Davis.

The face-to-face meeting of the two queens (above) provided much-needed dramatic intensity – something that both audiences and critics found lacking elsewhere in the film. One person who did not like the scene, however, was Viscount Mersey, who found the historical inaccuracy sufficiently disturbing that he complained about the film before the House of Lords on 9 December 1936:

On the night before her execution at Fotheringay Castle, Queen Elizabeth was made to go into Mary’s cell and have an altercation with her. It is common knowledge to those of your Lordships who are interested in the history of Queen Elizabeth and Mary Queen of Scots that they never met in their lives.

Lord Mersey then proposed a motion calling for ‘some form of control over the historical accuracy of films produced or shown in this country.’ After the Marquis of Dufferin pointed out that cinema’s presentation was little different from the romantic stories passed on by Shakespeare, Scott and Dumas, and that the fictitious meeting also appeared in Schiller’s Maria Stuart, Lord Mersey withdrew his motion.

Entertaining performances came from Douglas Walton (left), camping it up in lipstick and earrings as the effeminate Lord Darnley, and John Carradine as the queen’s Italian secretary Rizzio.

Entertaining performances came from Douglas Walton (left), camping it up in lipstick and earrings as the effeminate Lord Darnley, and John Carradine as the queen’s Italian secretary Rizzio.

Debate continues – albeit less formally – about Katharine’s performance, and indeed about her casting in historical films. In the early part of her career, she appeared in a series of 19th century period dramas – The Little Minister, Little Women, A Woman Rebels (notice a theme..?) – few of which stand comparison with the witty contemporary comedies in which she played characters more similar to herself.

To suggest that her best performances are those in which her characters are closest to her own personality, is not to diminish her acting skills. The distance between Mary, Queen of Scots and Katharine – in terms of both time and personality – challenged her, demanding more effort, and it is interesting to hear Kate’s voice in Mary of Scotland display far wider range and pitch than in her later films.

Part of the problem lay with Kate’s lack of empathy for her character. In her autobiography Me she recalled: ‘I never cared for Mary. I thought she was a bit of an ass. I would have preferred to do a script on Elizabeth.’ There is certainly little doubt that Kate would have excelled as Elizabeth. Both Ginger Rogers and Bette Davis had wanted the part but had been rejected by Ford. Davis only had to wait three years before playing the queen in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, adapted from another Maxwell Anderson play.

Hepburn returned to playing royalty later in her career, winning an Oscar for her performance as Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine in The Lion in Winter, which also starred the late Peter O Toole as King Henry II. Her success here was largely due to her ability to identify keenly with Queen Eleanor as a person: ‘She was something I’ve always tried to be — completely authentic.’

Sadly, the same cannot be said of Mary Stuart, whose downfall was brought about through a series of compromises and misplaced confidences. Kate, on the other hand, was far too sure of her own identity and opinions to let herself be shaped by others. Fiercely independent in spirit, she defied whatever conventions clashed with her style, and the drama critic of The Sunday Times summed this up succinctly in his review of Mary of Scotland when he wrote ‘Her accent was not of the Highlands, the Lowlands, nor a pure French equivalent. It was pure Hepburn, and nothing else.’

What else did we expect?

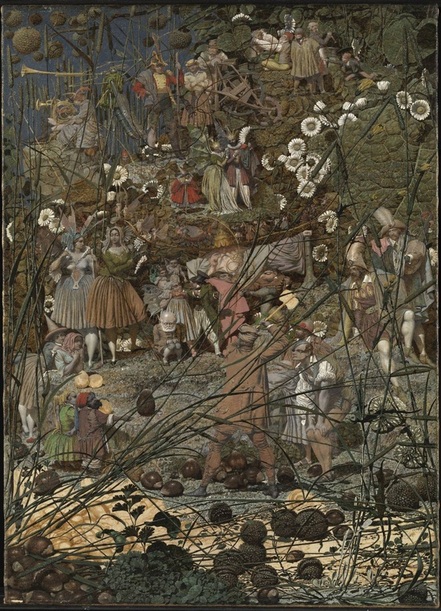

Richard Dadd The Fairy-Feller’s Master Stroke

Richard Dadd The Fairy-Feller’s Master Stroke