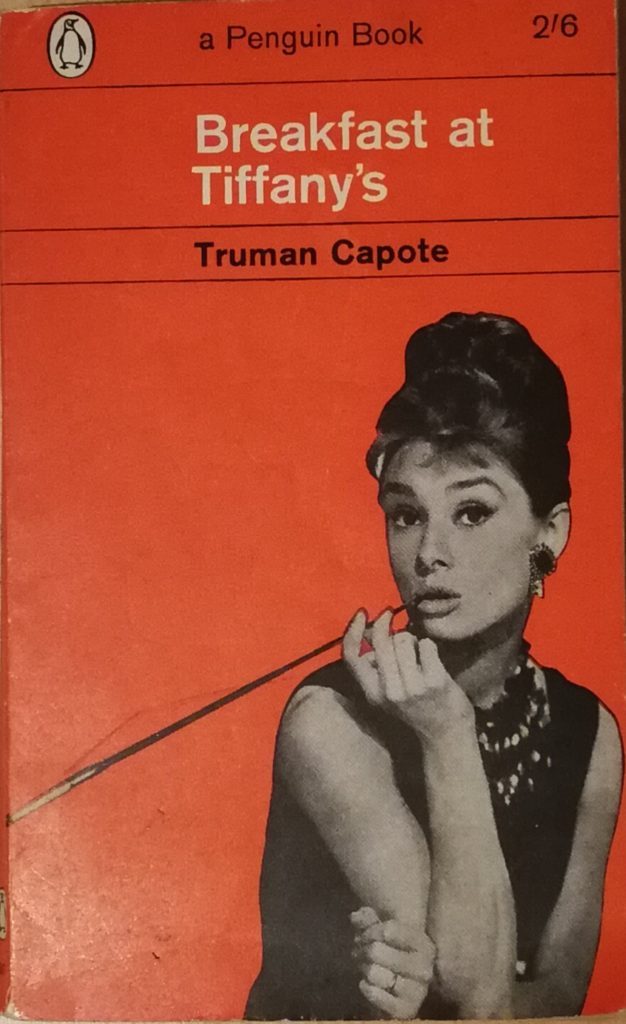

It is not unusual for classic film adaptations to eclipse their literary sources in popular culture, but even in the case of the most passionate book lovers, I doubt very much if anyone can hear the title Breakfast at Tiffany’s and NOT immediately think of Audrey Hepburn. So closely has the actress become associated with the character of Holly Golightly that it’s rather unsettling to realise that the author of the original short story, Truman Capote (1924-84), was not at all happy with the casting choice and thought she was altogether wrong for the role. Having seen the film many times, it seemed like a good idea this summer to pick up the book and read Capote’s short story again, doing my utmost to push Hepburn’s performance out my mind. A vain attempt, I should add, and one that was certainly not helped by the fact that my paperback copy has an image of Hepburn on the cover.

Although originally intended for publication in Harper’s Bazaar, Truman’s 50,000-word novella first appeared in the November 1958 issue of Esquire magazine. It was first published by Penguin in 1961, the year that the film was released, and my copy is from a reprint in 1964.

The story is told by an unnamed narrator some years after Holly’s departure from the New York brownstone apartment block where they were neighbours during the 1940s. Her current whereabouts are unknown, and the catalyst for the story is the discovery in 1956 of a photograph of an African wood carving that bears a striking resemblance to Holly – a strange element of the tale that made me for a moment think about Heart of Darkness, as I imagined Holly Golightly being idolised by some remote tribe in the middle of the jungle. The photograph was taken by one of their old neighbours, Mr Yunioshi, whose portrayal in the film by Mickey Rooney is unforgettable, for all the wrong reasons.) Idol worship aside, although Holly often appears to delight in being the centre of attention, she is not the shallow, gold-digging socialite that this might suggest, and one of the fascinating traits of the novella is how it plays with the reader’s presumptions about how characters should behave. Yes, she is self-centred and infuriating in her lack of consideration for others, but we gradually learn more of the hardship of her early life in Texas, and there are glimpses of real emotional depth in her powerful reactions to the death of her brother. She may be a party girl, but there is a great deal of pain in her life, most of it not of her own making. As the story unfolds, the reader learns more about how Lulamae Barnes of Tulip, Texas, became Holly Golightly, Travelling, of New York (and elsewhere) – a process that invites reflection upon the relationship between the past and the present: how much of Holly’s personality is an evolution of her experience as Lulamae and how much is a reaction against it?

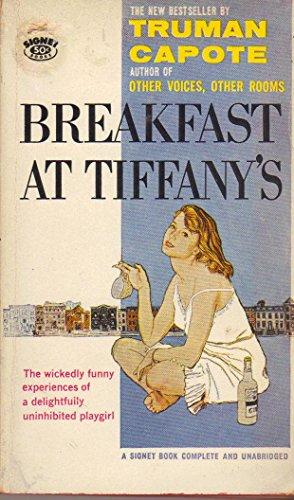

This is the only book cover I’ve ever seen that depicts Holly as someone other than Audrey Hepburn. It is well known that Capote wanted Marilyn Monroe for the part and actively campaigned for this.

There is a melancholy air to the novella, which is heightened by the sense of bittersweet nostalgia that comes from looking back on the events after thirteen years have passed. The happy ending that closes the film is entirely absent here, as are the clear-cut, clean-cut delineations of sexual identity and social convention. Holly makes it clear that such distinctions matter little to her, as she tells the narrator: ‘A person ought to be able to marry men or women or – listen, if you came to me and said you wanted to hitch up with Man o’ War, I’d respect your feeling. No, I’m serious. Love should be allowed. I’m all for it.’ The opening of the story suggests that all the men who gather to discuss Holly are still in love with her, each in their own way.

The precise nature of these loves is left undefined, with neither Capote nor his characters showing much inclination to pin their personalities and relationships down with hard-and-fast definitions or judgments. A great deal of their lives is messy and irresponsible, romances and trysts are multiple or overlapping, and their grasp on who they are, wish to be or pretend to be, remains elusive to themselves and the reader. It rings remarkably true as a reflection of what life is like (I feel) for most people, if they are truly honest.

There is much in the book to think about regarding truth and artifice, surface appearance and inner reality, so it is unsurprising to find many references to the film industry and to learn that Holly was at one point drawn to Hollywood: after running away from Texas she was picked up by movie agent O.J. Berman (the name surely recalls that of Pandro S. Berman of R.K.O.) who had her made over to be a film star, teaching her French to eliminate her Texan accent, and coaching her for an audition with Cecil B. DeMille before she ran away again, this time to New York. Like all the other men in Holly’s life, of course, he retains his affection for her and turns up at her parties. Among the many characters who weave in and out of her life, there is an aura of unreality created by their colourful names – Rusty Trawler, Sally Tomato, Sapphia Spanella – providing another reminder of names can act as a smokescreen behind which to conceal one’s true identity.

It is worth remembering that the film’s emphasis on Givenchy gowns, tortoiseshell Oliver Goldsmith sunglasses and Edith Head-designed outfits draws attention away from Holly and towards her external appearance, whereas the novella does the opposite: ‘there was a consequential good taste in the plainness of her clothes, the blues and greys and lack of lustre that made her, herself, shine so.’ Many books have been written presenting Holly/Hepburn as a style icon, as if that was the real essence of the character, the lesson of the tale – but reading Capote’s story in fact reveals that if anything could be considered sacred to Holly herself, it is personal integrity – even if misplaced and contradictory: ‘Be anything but a coward, a pretender, an emotional crook, a whore: I’d rather have cancer than a dishonest heart.’ Readers might find few moral certitudes in Holly’s perspective on the world, but Breakfast at Tiffany’s offers much to reflect upon about how individuals are perceived and presented, and how much we can really know about a person (even ourselves). The lesson offered here chimes with an observation often made about the finest American prose, of which Capote is a prime example – that sometimes, less is more.

This is the second in a series of blogposts written as part of the #classicfilmreading challenge for 2018