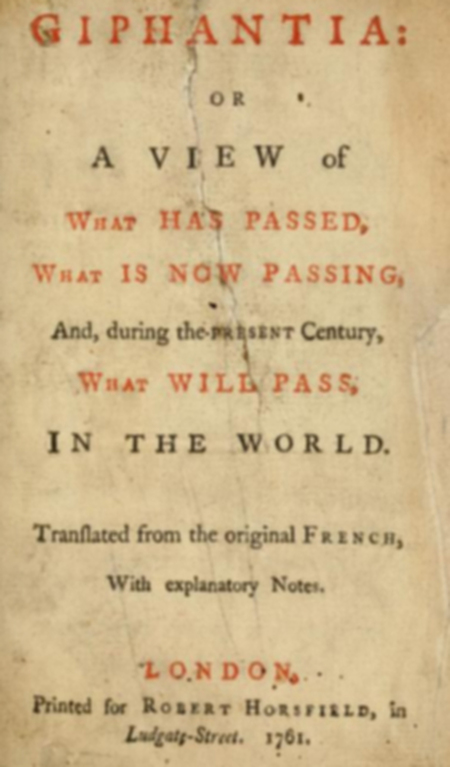

Recently I came across this intriguing passage in an 18th century French novel, Giphantia, which tells the tale of a man whirled up in a sandstorm and taken to a distant land where he meets the Elementary Spirits who guard the human race. The Prefect of the island shows him a series of wonders, including a globe-like mechanism by which ‘everything that passes in all parts of the world is seen and heard’ (Chap.VII) – the man is able to eavesdrop anywhere in the world by placing a rod against the globe, and by adding a mirror to the rod (Chap.XI) he is able to observe happenings across the earth. Unsurprisingly, his observations provide material for a series of wry Voltairean comments on human behaviour.

This is all what one might expect from 18th century France – the concept is not unlike that found in Zadig or Candide – but things take an intriguing turn in Chapter XVII, ‘The Storm’, when the author is shown a great storm through what he thinks is a window. But when he runs over to look out, his head strikes the wall and he realises that the images is projected onto a flat surface. As he relates the process by which this image was created, he seems almost to anticipate the invention of photography:

The Elementary Spirits (continued the Prefect) are not so able painters as naturalists; thou shalt judge by their way of working. Thou knowest that the rays of light, reflected from different bodies, make a picture and paint the bodies upon all polished surfaces, on the retina of the eye for instance, on water, on glass. The Elementary Spirits have studied to fix these transient images: they have composed a most subtle matter, very viscous, and proper to harden and dry, by the help of which a picture is made in a twinkle of an eye. They do over with this matter a piece of canvas, and hold it before the objects they have in mind to paint; The first effect of the canvas is that of a mirrour; there are seen upon it all the bodies far and near, whose image the light can transmit. But what the glass cannot do, the canvas, by means of the viscous matter, retains the images. The mirrour shows the objects exactly, but keeps none; our canvas shows them with the same exactness, and retains them all. This impression of the images is made the first instant they are received on the canvas, which is immediately carried away into some dark place; an hour after, the subtle matter dries, and you have a picture, so much the more valuable, as it cannot be imitated by art nor damaged by time.

pp.95-96

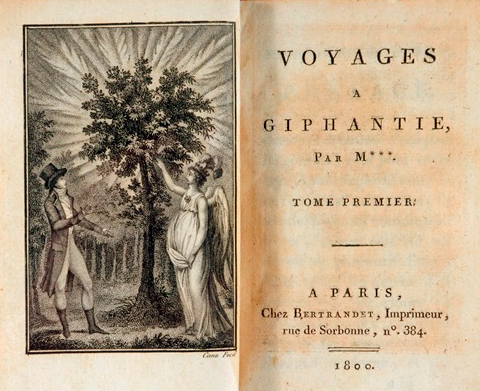

So who was the author of this extraordinary work? Well, there’s a hint in the title – ‘Giphantie’ is an anagram of ‘Tiphaigne’ and the writer, Charles-François Tiphaigne de la Roche, was born at Montebourg, Cotentin, on 19 February 1722. After studying medicine at the University of Caen he began practising as a physician in 1744, with his first writings appearing soon after. His medical training may have had some influence on his work, for his anonymous novels are a blend of science, rationalism, alchemy and magic:

L’Amour dévoilé; Ou, le système des sympathistes (1749) proposes a physical cause for human affection – namely, a form of sweat. It was later translated into English as Love Unveiled; Or, the Theory of Sympathism. The theory might seem far-fetched, but it represented a materialistic approach to human behaviour that was typical of the time, deliberately breaking away from conventional explanations of mutual attraction that drew on Christian theology and classical mythology. His next novel, Amilec, ou la graine d’hommes (Paris: Michel Lambert, 1753), uses the same dream/vision device as Giphantia, this time in order to explore the notion of inhabited planets while satirizing contemporary society. It was translated into English as Amilec, or the Seeds of Mankind (London : printed for W. Needham; and sold by M. Cooper, 1753.) Bigarrures philosophiques (1759), or ‘Philosophical Streaks’, comprises three sections – Visions of Ibrahim, Voyage to Limbo, and An Essay on the Human Soul, and was followed by the more conventional Essai sur l’histoire œconomique des mers occidentales de France (Paris : Chez Claude-Jean-Baptiste Bauche, 1760.) Returning to the fantastic, L’empire des Zaziris sur les humains, ou La zazirocratie (Pekin [i.e. Paris]: 1761) introduces the Zasiris, mysterious sylph-like beings who live among us on earth and influence human destiny. His final work, L’Histoire des Galligènes ou mémoire de Duncan (Amsterdam, Chez Arkstée & Merkus, Paris: La Veuve Durand, 1765) sees a Frenchman named Duncan shipwrecked on a distant island inhabited by the Galligènes, whose utopian society is founded on principles of common ownership, sexual promiscuity, free speech and religious tolerance.

Given the provocative nature of some of these ideas in pre-Revolutionary France, it is no surprise that Tiphaigne published these works anonymously. Giphantie was published in 1760 with the place of publication given as ‘Babylon.’

The visionary passage above might be dismissed as pure fancy, and its similarities to photographic methods pure coincidence – but this was almost eighty years before Talbot and Daguerre announced their discoveries, at least fifty years before Joseph Nicéphore Niépce began his experiments in what he called héliographie, and some thirty to forty years prior to Thomas Wedgwood’s success in capturing images on paper with silver nitrate. Sadly, Tiphaigne de la Roche did not live to see any of these – he died on 11 August 1774.

Those interested in reading more about this unusual author should consult Jacques Marx, Tiphaigne de la Roche: Modèles de l’imaginaire au XVIIIe siècle. (Brussels: Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 1981.)