Category Archives: Horror

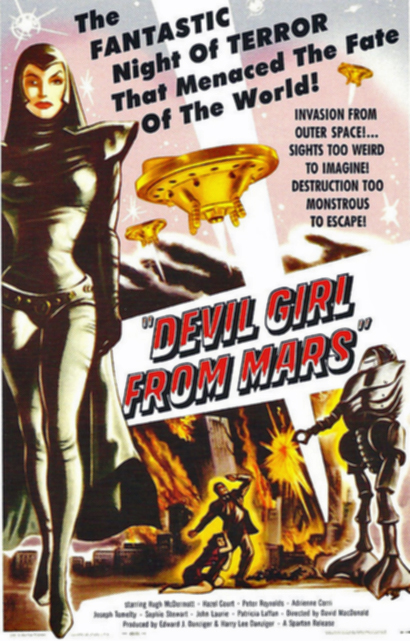

Devil Girl from Mars (1954)

Thirteen years before Mars Needs Women, the red planet was apparently running drastically low on the other sex. To balance the numbers, a female Martian named Nyah – clad in black leather and accompanied by a giant robot – travels to earth on a mission to round-up suitable males for breeding…

This is the premise of Devil Girl from Mars (David Macdonald, 1954), a curious movie that certainly fits the ‘accidentally hilarious’ category, but also one that possesses some unusual quirks which set it apart from other science fiction B-movies of the decade. Distinctly British in its approach and execution, Devil Girl from Mars is played with a seriousness that contrasts starkly with its low-budget effects and stage set.

The basic concept was by no means unique, for the early 1950s saw a wave of Hollywood movies about alien intruders, including The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), The Man from Planet X (1951), The Thing from Another World (1951), Invaders from Mars (1953) and The War of the Worlds (1953.) Without denying that these films may have had some influence, Devil Girl from Mars was a British production and feels very different from the American science-fiction movies it might have imitated. There are elements of the ‘country house mystery’ in the way disparate characters are drawn to the remote inn, a concern for matters like social class, moral behaviour, justice and redemption – plus a very British appreciation for tea and other beverages. Some of these elements betray the film’s radio play origins, although I have been unable as yet to trace any broadcast details. In structure and pacing the film remains stagebound, with its limited locations, excessive speechifying and over-reliance on dramatic entries and exits.

None of this can be anticipated from the film’s opening shots, however, in which an aircraft is mysteriously destroyed in mid-air. The mystery is not just in the mode of destruction, but also in its relevance to the story: it is never explained what this has to do with Nyah’s mission.

Following the plane explosion and the title credits, the scene switches to the Bonnie Charlie Inn ‘in a lonely part of Inverness-shire,’ which will be the setting for the rest of the film. Despite being closed for the winter, there are four staff in residence – Mr and Mrs Jamieson (John Laurie and Sophie Stewart), barmaid Doris (Adrienne Corri) and handyman David (James Edmond) plus Mrs Jamieson’s young nephew Tommy (Anthony Richmond). They have only one guest, glamorous model Ellen Prestwick (Hazel Court), who has come here to hide from her married lover.

This small household is soon bolstered by the arrival of escaped convict Robert Justin (Peter Reynolds), who was actually Doris’s lover before he was jailed for killing his wife, although her death appears to have been accidental: (and as Doris points out in his defence, ‘she was bad’.) Doris took the job at the Bonnie Charlie in order to be nearer Robert, although one wonders why she didn’t choose a pub nearer Stirling, which must be at least a hundred miles away. She might have been safer too, given the apparent pickpocketing powers of fish in the Highlands:

Isn’t it awful, Mrs Jamieson? He’s lost his wallet, he’s just been telling me…There he was crossing the stream, and he..he looks over to see a fish that’s in the water, and the next thing he knows…his wallet’s gone.

Mrs Jamieson will not withhold the Highland tradition of hospitality, but she gives Robert a suspicious look and warns him, ‘I’m counting the spoons.’

Next to arrive are Professor of Astrophysics Arnold Hennessy (Joseph Tomelty) and reporter Michael Carter (Hugh McDermott) from the Daily Messenger, who got lost in their car on their way to investigate reports of a meteor.

Nyah’s explanation of the repair process introduces the first of several technical discussions: we learn that the spaceship is made of organic metal that repairs itself by regeneration. The concept of a ‘living spacecraft’ was, I think, quite original at this time. A short while later Professor Hennessy quizzes Nyah on her spaceship’s power source:

N: A form of nuclear fission, on a static negative condensity

H: A negative condensity?

N: Exactly. Your atomic bomb is positive, it can cause an explosion to expand upwards and evaporate; our force is negative and explodes atomic forces into each other, thereby magnifying the power a thousand fold.

H: And the fuel?

N: Self-propagating

The science may be flaky in the extreme (don’t ask about the ‘perpetual motion chain reactor beam’), but there is something impressive in the deadpan seriousness with which it is presented. Despite its campy and unintentionally comic elements, this is an ambitious little film.

How many earth men could Nyah have fitted in here?

How many earth men could Nyah have fitted in here?

The notion of the self-repairing spaceship is crucial to the plot. Nyah is stranded at the Bonnie Charlie for ‘four earth hours’ until her ship is ready to fly again, forcing her to kill time with the inn’s residents while she waits. Viewers of the film start to feel much the same way, as an inordinate amount of time is spent watching characters wander backwards and forwards between the spaceship and the inn. Did Nyah travel 200 million kilometres for this?

The purpose of her one-woman invasion of earth is really to test the capabilities of the organic spacecraft, in preparation for a much larger ‘man-hunt’ that will follow shortly. Nyah therefore shows little interest in kidnapping any of the five males at the inn. She takes little Tommy, but then is persuaded by Carter to let him swap with the boy. After Carter has wandered back to the inn, Hennessy strolls out for a look around the spaceship and offers to accompany Nyah to London to act as a guide. She agrees, but he is soon back in the Bonnie Charlie as well. When the ship is repaired and she is ready to leave, everyone is hiding down in the cellar except Robert….

The three women may not be at risk of being whisked back to Mars, but they are as determined as the men are about stopping Nyah’s mission. When Carter introduces the Devil Girl to Mrs Jamieson, the landlady is given one of the best lines in the film:

– ‘Mrs Jamieson, may I introduce your latest guest, Miss Nyah. She comes from Mars.’

– ‘Oh, well, that’ll mean another bed.’

The earthlings face the alien threat with the sort of stiff upper lip and cheeriness typical of British wartime movies. Mrs Jamieson exemplifies the spirit of the Blitz with her down to earth remark:

‘While we’re still alive, we might as well have a cup of tea.’

Tea is not the only beverage drunk at the inn, and copious amounts of alcohol are drunk by Mr Jamieson and Carter in particular. I find it quite refreshing when films of this era depict heavy drinking in such a matter of fact way, without either moral judgment or any suggestion that large and frequent tipples are indicative of a problem.

Patricia Laffan was best known at this time for playing Nero’s vixenish wife, Queen Poppaea, in Quo Vadis? (1951), a film in which Adrienne Corri had a minor role. Laffan excelled in long-legged imperious arrogance.

Devil Girl from Mars actually has a pretty good cast compared to similar B-movies of the era:

Shades of Dad’s Army – ‘Shoot, man, shoot!’

Shades of Dad’s Army – ‘Shoot, man, shoot!’

Devil Girl from Mars is probably best remembered for two costumes: Nyah’s black PVC dominatrix uniform and Chani’s cardboard fridge & styrofoam coffee-cup arms. These Martian invaders make an odd couple, and though they were clearly inspired by the pairing of Klaatu and the robot Gort in The Day the Earth Stood Still, they fall far short in terms of effective teamwork and combined resources. Despite her impressive robot, powers of hypnosis and ability to enter the fourth dimension, Nyah’s mission turns out a spectacular failure. At the end of the film, is there a moral as to why?

The inability of the Martian women to procreate is symbolised by Nyah’s pairing with the mechanical Chani; furthermore both of them show a total absence of feeling throughout the film. In contrast, the Bonnie Charlie is a hotbed of romance and warm emotions, even in the depths of winter: Doris and Robert are reunited and both show willingness to sacrifice everything to protect the other; Ellen falls for Carter, finding the strength to break away from her married lover while succeeding in breaking through Carter’s cynicism and gruff exterior. Behind the Jamiesons’ constant bickering banter, there seems to be a steadfast relationship and a tender devotion to their young nephew. The cheesy dialogue and over–wrought domestic dramas may well amuse modern viewers, but they show that Devil Girl from Mars was looking in the opposite direction from most of its contemporaries. This is not another Cold War metaphor or guilt-ridden nightmare about atomic power. Devil Girl borrows the trappings of 1950s science fiction while exploring some fairly old-fashioned British themes about love, duty, altruism and moral principles. The similarity between Nyah’s black-booted outfit and the Nazi uniform is surely no coincidence; this is a flying saucer movie that looks to the past as much as the future.

This blog post is part of the ‘Accidentally Hilarious’ blogathon, and there’s some brilliant pieces on other classic films – including silent movies, the work of Ed Wood, more monster/alien flicks and all sorts of wonderful weirdness – to be found here. Enjoy!

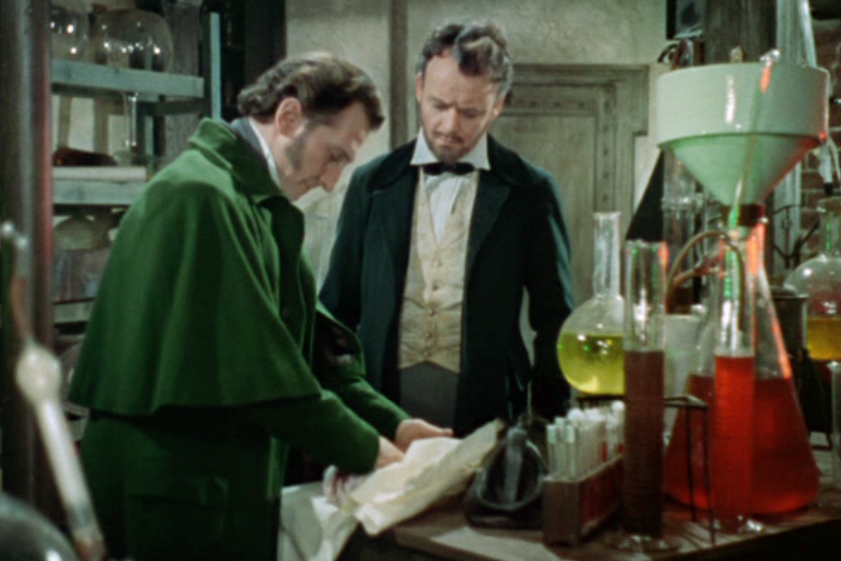

The Curse of Frankenstein

This was the first horror film in which Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee appeared together, and the pair would co-star in around twenty others, many of them Hammer productions. For copyright reasons Hammer needed to distinguish their imagery from James Whale’s 1931 classic, and make-up artist Phil Leakey made Christopher Lee look very different from Boris Karloff’s creature. The contrast is more than skin deep, however – Lee plays the creature as a brain-damaged monster, with little apparent capacity for thought or emotion; it is hard for modern audiences to feel much sympathy for him, especially given the creature’s lack of screen time. The physicality of Lee’s performance is astonishing nonetheless; jerking, flailing and lurching, he captures the tragedy of a being unable to controls its own limbs.

The real monster of the film is Victor Frankenstein, who is prepared to sacrifice everything – ethics, friendship, his fiancee, mistress and unborn child – for science. Peter Cushing’s performance is impeccable; the subtlety of his facial expressions seemed much more impressive on the big screen. He returned in this role for another four films, all directed by Terence Fisher: The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Frankenstein must be Destroyed (1969) and Frankenstein and The Monster from Hell (1974.) In 1958 he played Von Helsing opposite Lee’s Count Dracula, and the two of them would continue to reprise these roles – with constant variations – over the next two decades. Hammer Film Production’s reputation as purveyors of luridly-coloured Gothic gore began with The Curse of Frankenstein and the film contains motifs that would recur again and again in the studio’s output.

Another highlight of the film was the lovely – if rather underused – Hazel Court, playing the part of Frankenstein’s fiancee Elizabeth. She gets to wear a series of ravishing costumes in the film, of which the gown below is probably the finest. Not ideal for grubbing around a dungeon full of chemicals, but certainly a feast for the eyes. Hazel was a classically trained actress and had done several films before The Curse of Frankenstein – hence my regret that her character is so under-developed. Elizabeth is a typical heroine-victim in the Gothic tradition, entering a house of horror (both building and family lineage, as in the House of Usher) through marriage, and thereby trespassing upon dark secrets that threaten to engulf her. A comment by Paul Krempe indicates that Frankenstein had forbidden Elizabeth to look behind his laboratory door – a prohibition that recalls the legend of Bluebeard’s Castle – but of course she does…

Certain elements of the plot are reminiscent of other Gothic narratives, and there is a parallel with Gaslight in the baron’s flirting with the maid behind his fiancee’s back. He is ultimately punished for his immoral behaviour and the innocent Elizabeth finds refuge with Frankenstein’s friend and former tutor Paul Krempe, who is often regarded as the film’s moral compass. Despite his sanctimonious pontificating, however, his conduct seems to me as murky as the baron’s. He knows that Frankenstein’s experiments are unethical and repeatedly warns that their work ‘can only end in evil’, yet he keeps returning to help and evidently cannot resist his fascination with Frankenstein’s project. As his mind has not been corrupted to the extent that Victor’s has, Krempe arguably has more capacity to end the wickedness, and so his failure to act makes him even more culpable. His final silence not only conceals his part in the baron’s work, but also offers a neat way to remove Elizabeth’s fiance from the scene when it is obvious that he wanted her for himself all along. Just as Frankenstein got rid of his former lover when she began to get in the way, so too does Krempe callously dispose of his friend, using the executioner in much the same way that Frankenstein used the creature. (Although if the 1958 sequel The Revenge of Frankenstein is to be believed, the baron evades the guillotine and returns to his work.)

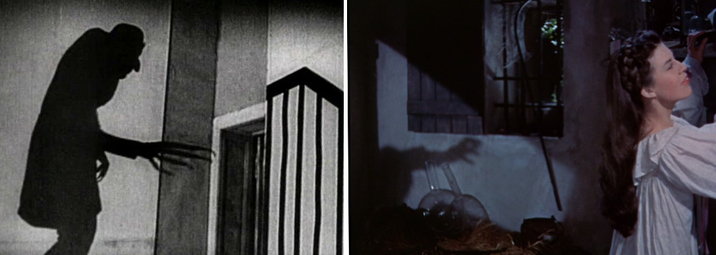

There is always the temptation, of course, to read more into these old films than their makers ever intended. Screenwriter Jimmy Sangster has been frank about the extent to which his work was driven by purely commercial concerns, admitting his bewilderment when Hammer fans ask him about Freudian symbolism, literary echoes and other esoteric nuances that they detect. That is not to say that such motifs are actually absent. Fisher may have wished to create a definite distance between The Curse of Frankenstein and Universal’s 1931 movie, but his film – consciously or unconsciously – contains clear homages to classic horror tradition, e.g.

Nods to Nosferatu

Seasons of Mist

This was the view from my bedroom window a couple of days ago, and when driving up through the Exe Valley last week I noticed thick banks of white mist hanging over the fields to the side of the road and thought of Keats’ lines in Ode to Autumn:

Seasons of mist and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun.

Autumn is almost upon us now, and I like the pleasing contrast between the white mist and the piles of bronze and gold leaves that are starting to accumulate on the ground. I call it ‘mist’ rather than ‘fog’ because I’ve always associated the latter with the sea. Strictly speaking, however, the distinction lies in visibility: fog is thicker than mist, and there is a precise point at which one becomes the other. Hill-walkers, drivers, seafarers, pilots and others have good reason to dislike such treacherous conditions: routes are hidden from view, dangers concealed, sounds are muffled and distances become hard to judge. Fear of what lies within the mist, or fog, is also a familiar trope from the worlds of film and literature. Perhaps the most notorious example would be London’s ‘pea-souper’ fogs, which have provided the atmosphere (literally) for numerous acts of murder and skulduggery by Victorian villains.

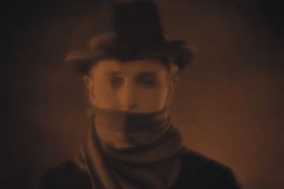

Contrary to popular belief, Conan Doyle never used the term ‘pea-souper’ in his Sherlock Holmes stories. Another common misconception is that the Whitechapel murders ascribed to ‘Jack the Ripper’ took place in thick fog, when in actual fact the killings ceased during the month of October 1888 – the only time when there really was a pea-souper. These murders provided the inspiration for Hitchcock’s silent thriller The Lodger (1927), starring Ivor Novello as the suspected serial killer. Its full title is The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog. Although Novello’s appearance matches the description of the killer as ‘wearing a scarf over the lower part of his face’ (above) many Londoners at this time would have masked their faces in the same or similar ways to protect themselves from the damp unhealthy air. Is the lodger the killer? Viewers’ inability to decide is just another aspect of the fog’s power to dull our powers of perception.

There is more confusion over mistaken identity in the film Footsteps in the Fog (1955), set in the early 1900s and based on a short story by W.W. Jacobs, the author of the classic horror tale The Monkey’s Paw. It starred the then husband and wife team of Stewart Grainger and Jean Simmons, caught up in a dark plot of murder and blackmail. The basic set-up – murderous husband teaming up with flirty maid – recalls the dysfunctional household in Patrick Hamilton’s Gaslight which was filmed in 1940 by Thorold Dickinson and then remade in Hollywood in 1944. Again, fog is used to hint at villainy – when we first see Paul Mallen (Anton Walbrook) leave the house and sets out on one of his nocturnal missions (below).

Sergeant Rough, wrapped up against the London fog with the same thoroughness as Ivor Novello – although falling short of the latter’s sartorial elegance – is able to use the fog as a cover for following Mallen as he crosses the square.

Gaslight was set around 1885, but as late as December 1952 thousands of Londoners died during a dense smog that enveloped the capital for several days. This led to the Clean Air Act (1956) which sought to banish black smoke in urban areas through the introduction of smokeless fuels. It took many years, but London’s pea-soupers eventually became a thing of the past. Times were changing in other ways, as the televised Coronation in March 1953 encouraged huge numbers of British households to invest in TV sets. The 1950s are now regarded now as the ‘golden age of science fiction’ and programmes made for television began exploring themes of space travel, frightening technology and strange creatures from other worlds. Most of these were aimed at young audiences, but a six-part series The Quatermass Experiment – broadcast in six half-hour episodes on Saturday evenings in July-August 1953 – was aimed at adults, and proved amazingly popular: when the last episode was broadcast on 22 August 1953, audience figures were estimated at around 5 million. The film industry took notice, and Hammer Films bought the rights, releasing The Quatermass Xperiment in cinemas in 1955. In America, it was renamed The Crawling Terror and was equally successful.

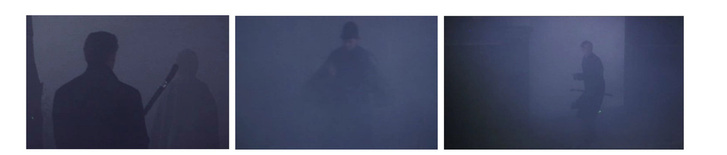

Although less famous, The Trollenberg Terror followed a similar trajectory to Quatermass. Occupying the same Saturday evening slot, it was broadcast in six episodes between 15 December 1956 and 19 January 1957, and then quickly bought up and remade into a film for release in 1958. In America it was renamed The Crawling Eye, possibly to capitalise on audience’s familiarity with the Quatermass film, although ‘crawling eyes’ is a perfect description of the monsters. Their appearance, however, is concealed until the end of the film by a cloud of mist; this aspect of the film, one might argue, was a direct influence upon later horror films such as The Fog (1980) and The Mist (2007.)

Most of the action takes place on the Trollenberg, a mountain in the Swiss alps which has been partially covered by a mysterious cloud that remains static over the south slopes. The phenomena is being monitored by scientists from a nearby observatory, led by Professor Crevett (actor Warren Mitchell, soon to become better known as Cockney bigot Alf Garnett), who has detected high levels of radioactivity in the cloud. This is not the only sinister happening: since the cloud’s appearance, mountain climbers have been found with their heads torn off. Crevett is joined by his old friend Alan Brooks, a United Nations expert who investigated similar goings-on in the Andes three years earlier. He arrived at Trollenberg along with two sisters, Anne and Sarah Pilgrim.

Anne Pilgrim (played by the lovely Janet Munro) is in fact telepathic, and has just finished performing a mind-reading show in London with her older sister Sarah (Jennifer Jayne.) Later, Anne’s psychic powers forge a link with the alien creatures in the mist, allowing her to visualize events on the mountainside and direct rescue operations. The aliens sense her power and try to have her killed by human ‘zombies’ whose minds they control. The presence of the sisters is one of the more intriguing elements in a film that – although full of absurdities – I have enjoyed watching several times.

John Carpenter saw The Crawling Eye as a child, and provided at least some of the inspiration behind his film The Fog (1980.) During their commentary for the 2002 special edition DVD of The Fog both he and producer Debra Hill refer to it as one of their favourite films. Carpenter’s image of the fog billowing under Dan O’Bannon’s doorway and entering his room is just one of several incidents that are reminiscent of those that took place on the Trollenberg. Another source of inspiration was a visit to Stonehenge made by Carpenter and Hill in 1977 when they witnessed a fog bank ‘just sitting on the horizon, way past Stonehenge’ causing Carpenter to wonder ‘what if there’s something in that fog?’

The malevolent beings concealed within the fog are, in this film, ghostly rather than alien: exactly one hundred years earlier, in 1880, the founders of the Antonio Bay community lit false beacons to lure a ship onto the rocks – a cruel trick allegedly employed by wreckers in Devon and Cornwall in years gone by (as depicted in Jamaica Inn for example), although there seems to be little documentary evidence to support these tales. All those aboard died in the wreck, but their vengeful spirits have returned on the night of the town’s centenary celebrations, and are intent on claiming the lives of six descendants of the original murderers.

The horrific killings take place within an eerie bank of glowing fog, that rolls in from the sea. As in The Trollenberg Terror the cloud of fog defies nature, moving against the wind. Local radio broadcaster Stevie Wayne (played by Carpenter’s then wife Adrienne Barbeau) plays a key role in the night’s events, as her radio station is located in a lighthouse overlooking the bay. From this vantage point she is able to provide a running commentary on the inexorable progress of the fog to her listeners. For me, the most memorable part of the film is listening to her voice:

‘It’s moving faster now, up Region Avenue, up to the end of Smallhouse Road…just hitting the outskirts of town…Broad Street…Clay Street… It’s moving down Tenth Street, get inside and lock your doors, close your windows…there’s something in the fog. If you’re on the south side of town, go north. Stay away from the fog…Richardsville Pike up to Beacon Hill is the only clear road. Up to the church. If you can get out of town, get to the old church. Now the junction at 101 is cut off..if you can get out of town, get to the old church. It’s the only place left to go. Get to the old church on Beacon Hill.’

Oddly enough, in James Herbert’s novel The Fog an empty church is also a place sought for sanctuary – but it is the fog that takes refuge there, rather than its victims. Apart from sharing the same name there is no relation between Carpenter’s film and Herbert’s novel, which was published in 1975. Interesting to note, nonetheless, that both men turned to the theme following their first big breakthrough. After a few minor films, Carpenter had just enjoyed his first great commercial success with Halloween (1978) and invited several of the actors to take roles in The Fog. Herbert’s first novel The Rats (1974) had sold out within weeks and attracted a great deal of attention – not all of it positive by any means – due to the graphic descriptions of death and violence. The Fog was written in the same vein and expanded upon The Rats’ theme of natural disaster brought upon by misguided government experiments; this would also form the basis of Stephen King’s novella The Mist. Herbert’s tale begins in Wiltshire when an earthquake unleashes a foul yellow fog that erupts from a crack in the earth and begins drifting through the southern counties of England. Those who are caught by it are affected mentally and the novel progresses through a series of horrific episodes in which the madness leads to murder, mass suicide, mutilation and sexual violence. The fog here does not conceal any monster other than itself; the fog is the horror, and it is slowly revealed that is has a biological life of its own.

The horror within Stephen King’s Mist shares more similarities with that of the Trollenberg cloud than either of the Fog stories. The first film Stephen King remembers seeing was The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), and he was about eleven years old when The Crawling Eye was released in the USA. The film is referred to in his 1986 novel It, which is set around the time of the film’s release in the summer of 1958. King’s youthful immersion in popular culture – early horror and science-fiction films, radio drama serials such as Dimension X and E.C. comics like Tales from the Crypt – were important influences on his later writings.

‘There’s something in the mist!’

There are a few superficial parallels between The Trollenberg Terror and the 2007 film The Mist, which was director Frank Darabont’s adaptation of King’s novella of the same name, first published in the Dark Forces collection (1980). I was on holiday in Cornwall when I first read the story in 1985, after it had been republished in another anthology, Skeleton Crew. It is by far the longest story in the collection but I read it all in one continuous session, curled up in a dormitory bed with my borrowed book and a packet of biscuits. It made quite an impression on me, and the only other story I can remember from that collection is The Raft. My vision of the scenes differed rather a lot from that of Frank Darabont, who had already brought two of King’s other stories to the screen – The Shawshank Redemption (1994) and The Green Mile (1999.) Many of King’s fans were displeased at the shocking twist – not in the book – with which Darabont decided to end the film. Personally, I approve of the ending. Few modern horror films contain genuine shocks; the final frames of The Mist have an undeniable impact that has unsettled audiences. The ending neatly confirms what has been true of all the films above – fog and mist not only conceal terrifying threats, but they cloud judgment as well as vision, rendering opaque the distinction between innocence and guilt

So when I’m walking across the fields again this week and happen to see banks of mist (or worse still, fog) drifting over the ground towards me, the question is bound to come to mind….what lies within?