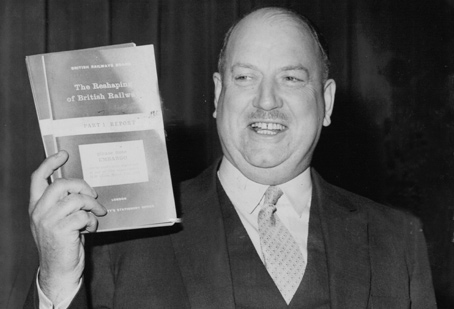

His reform programme had begun in 1963 with the publication of The Reshaping of British Railways (above), while this second report, a 100-page document entitled Development of the Major Railway Trunk Routes, developed his initial argument that the future of rail lay with high-volume traffic on core routes – thus sealing the fate of hundreds of lightly-used passenger services. Although the former chairman of British Rail insisted that ‘This report is not a prelude to closures on a grand scale’, the Beeching Plan eventually led to the loss of a quarter of the rail network and the closure of over 2,000 stations.

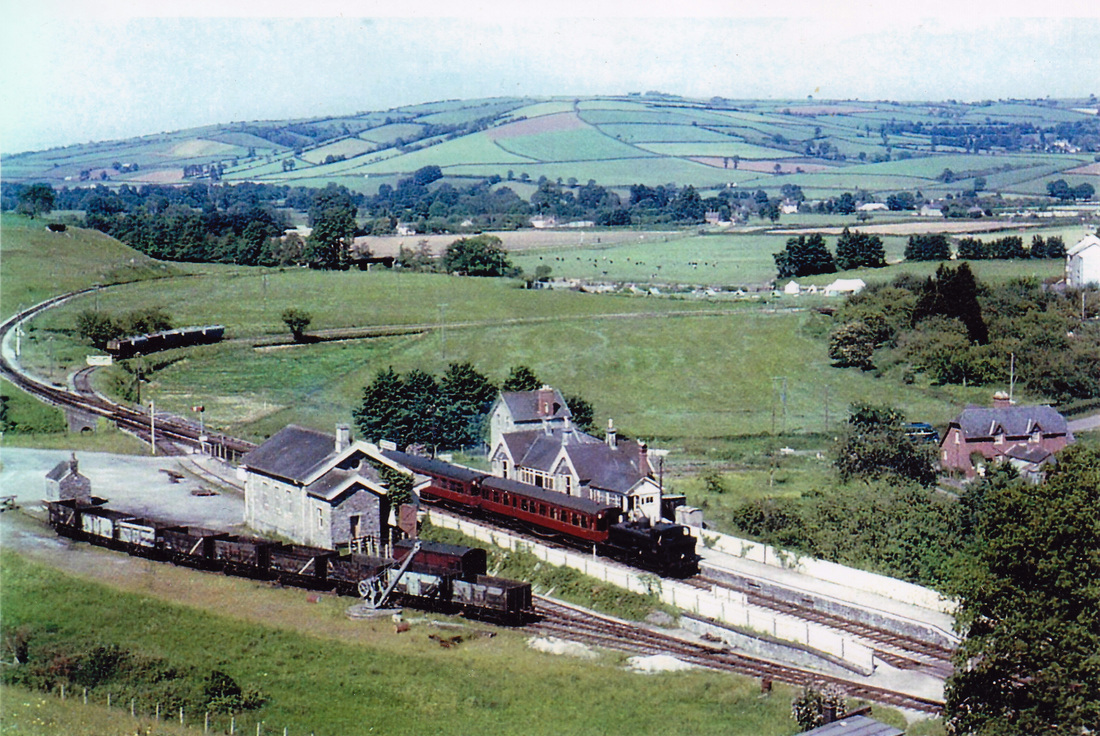

Thorverton was one of the stations that was closed, although Beeching was not entirely to blame for this. According to a note on p.133 of The Reshaping of British Railways (1963), its closure – and that of the entire Exeter-Dulverton line (p.129) – was already ‘under Consideration….before the Formulation of the Report.’ Beeching had been commissioned to draw up the report in response to increasing financial losses on the railway network – a sign that the 1955 Modernisation Plan was not working.

By that time, trains had been steaming through Thorverton for seventy years. The Exe Valley branch line, running from Exeter St Davids to Tiverton – through Stoke Canon, Brampford Speke, Thorverton, Up Exe and Cadeleigh – had opened in 1885 and formed part of the Great Western Railway.

The negative effects of ‘Beeching’s Axe’ are easy to see – the loss of rail services meant that many rural communities became isolated, forcing the closure of shops and other businesses, as well as the migration of villagers who found it impossible to commute to work. Replacement bus services were inadequate from the outset, and were often withdrawn shortly afterwards. Many small town and villages went into terminal decline from which they never recovered.

Some of his opinions were valid – the financial losses were unsustainable, and the duplication of routes inefficient – but more careful consideration might have reduced some of the long-term damage to rural communities. As it turns out, the rising costs (financial and ecological) of a massive increase in car usage have shattered 1960s optimism about the rosy future of British motoring. The expense of keeping and running a car, along with the appalling congestion of major routes, are tending to reverse Beeching’s predictions as commuters abandon their cars and take to the trains again. The Exe Valley Line may have gone for good, but in the near future entirely new rail stations will be opening at Marsh Barton and Cranbrook. Will they still be operating in 85 years time? Or will the 21st century raise up another Dr Beeching to reassess their economic viability? Time will tell.