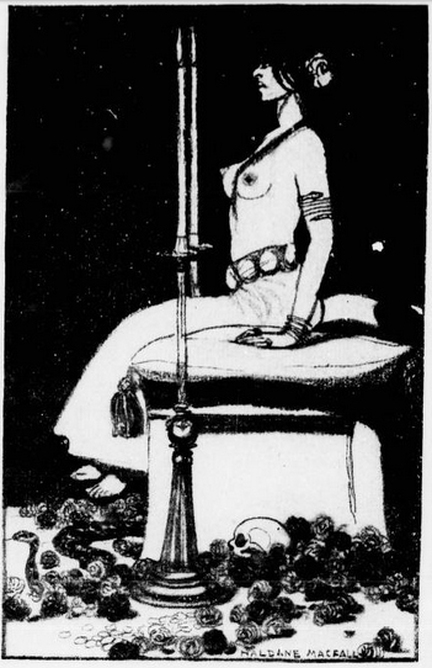

Macfall’s literary career began while serving in Africa with the West India Regiment in the 1880s, when he began writing about his experiences for The Graphic. A skilled artist, he also contributed illustrations to the magazine, designed bookplates, decorated books and exhibited at the Royal Academy.

Quite apart from my interest in Whistler, I was attracted to the book’s design and page layout, and particularly intrigued by the presence of hand-drawn pencil sketches opposite the opening page.

There is nothing here to identify the artist, although there seem to be quite a few copies of Macfall’s books in circulation bearing pencil sketches on their blank pages.

Chambers Haldane Cooke Macfall was born in 1860 but lost his mother when he was still young. His father Surgeon-Major David Chambers McFall (1833-98) remarried in 1871, and his new bride – Frances Clarke – became stepmother to Haldane and his brother Albert. At sixteen, Frances was only six years older than her eldest stepson, and within a year she gave birth to a boy named Archibald. The Macfalls spent five years in the Far East, returning to England in 1876, but the marriage proved an unhappy one. Frances left her husband in 1890, subsequently changing her name to Sarah Grand.

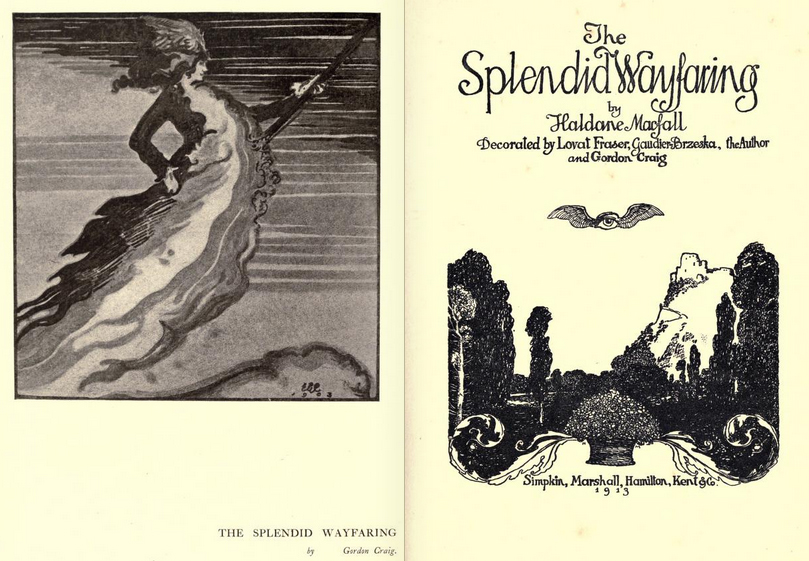

Sarah was a forceful campaigner for women’s rights and a prolific writer of both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Heavenly Twins (1893) sold over 20,000 copies and caused some controversy due to its strong feminist message and frank treatment of medical matters relating to sexual behaviour. She was active throughout the 1890s, lecturing on topics such as women’s suffrage and rational dress. In 1898 Haldane McFall moved in with his step mother, having been forced to leave the army due to a serious bout of fever. His first novel The Wooings of Jezebel Pettyfer was published the same year. His next novel, The Masterfolk (1903) was a witty portrait of Bohemian life in London and Paris in the 1890s, declared by Vincent Starrett – in his essay on Macfall in Buried Caesars (1923) – to be ‘the last word on the English decadents.’ Other novels include Rouge (1906) and The Three Students (1926), while his biographies included Ibsen: The Man, His Art & His Significance (1903), Sir Henry Irving (1906), Fragonard (1909), Boucher (1911) and a spirited defence of his friend Aubrey Beardsley (1928.) He returned to the army to serve during World War One, and published a number of books and essays on military topics. He collaborated several times with the artist Claud Lovat Fraser, who – along with Edward Gordon Craig – provided illustrations for Macfall’s essay on art and aesthetics, The Splendid Wayfaring (1913.) Macfall seems to have been on friendly terms with both artists. Gordon Craig’s father had been a friend of Whistler’s, and he was godson of another of Macfall’s biographical subjects, Henry Irving. He engraved bookplates for both Macfall and his wife Mabel, and wrote an appreciation of Macfall after his death.

Whistler exercised a considerable influence on the aesthetic movement in Britain – not only through his artwork, but also by his insistence on the autonomy of art, which he believed existed for its own perfection rather than for didactic purposes. Wilde had made a similar argument during his 1895 trials, and Whistler also found himself defending the notion in court during the libel case that followed Ruskin’s slur on the artist’s Nocture in Gold and Black. By contrast, Whistler’s response to reading some of Macfall’s art criticism was apparently ‘Ha ha, this man knows.’ It was probably just as well that he found nothing to offend, for Whistler made a formidable enemy – the waspish wit collected in The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1890) may amuse readers, but being on the receiving end of Whistler’s wrath was far from pleasant.

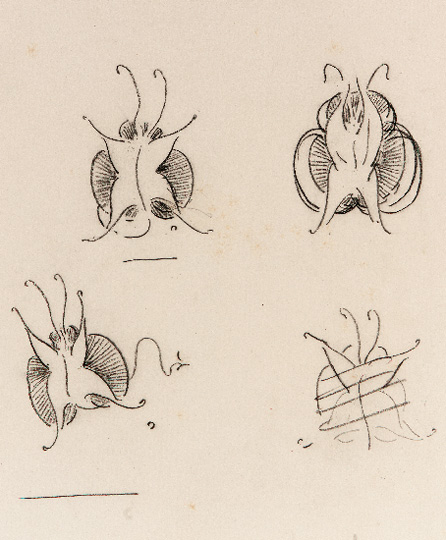

This aspect of Whistler’s work was symbolised in the butterfly monogram that appears on the cover of Macfall’s book and elsewhere inside. The artist used this on his paintings in place of a signature from 1869 onwards, basing it on his initials ‘J.W’ but developing a series of variations over the years. When using the monogram to sign his more acerbic correspondence, he would give the butterfly a stinging tail.