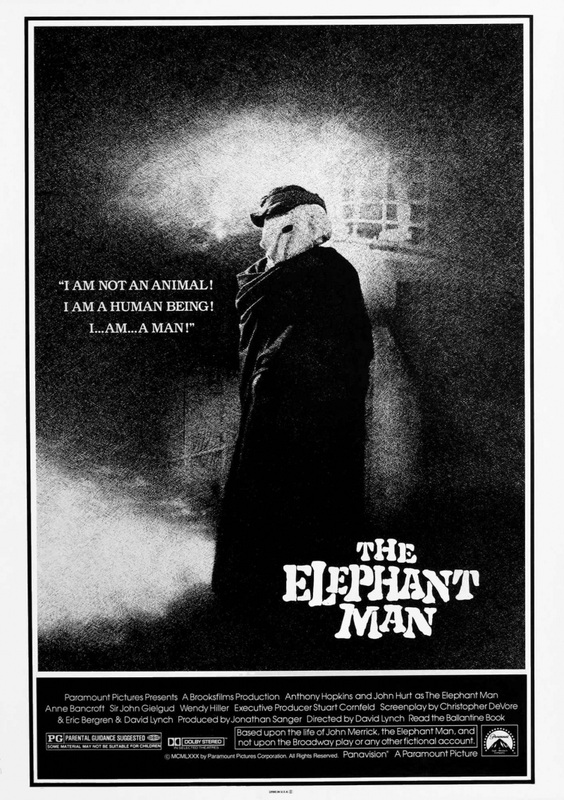

It has been many years since I last saw The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980), and a considerable time too – although somewhat less – since I last sat in a cinema with tears in my eyes. Last night I revisited both experiences, thanks to a special screening of the film as part of Exeter University’s Screentalks series. What follows below is just a series of scattered thoughts and impressions, written without the usual care applied to my blog posts.

Sometimes The Elephant Man is described as an anomaly in Lynch’s oeuvre, its period setting, factual basis and star-studded cast distancing the film from the highly original and darkly surreal narratives of his other projects. Such an opinion seems convincing on paper, even in conversation, but when watching the film on the big screen one cannot fail to be impressed by the powerful motifs familiar from other David Lynch movies: the bleak monochrome industrial landscape and off-screen synthesised drones of Eraserhead (1977), the use of dream sequences and visions reminiscent of Wild at Heart (1990) or an anxiety about the infernal worlds that lie beneath and behind the respectable facades of society, disturbingly portrayed in Blue Velvet (1986.)

In her introductory talk, Corinna Wagner drew attention to the Gothic elements of the film, including the preoccupation with dark secrets, with what is hidden behind the surface. Episodes during Merrick’s early period in the hospital evoke Gothic tropes, such as the ‘madwoman in the attic’ of Jane Eyre or the ‘horror behind the door’ of Bluebeard.

The threat of ‘what lies beneath’ is depicted quite literally in several sequences, where the camera appears to drop beneath the streets of London to glimpse a labyrinthine network of tunnels and serpentine pipes, shadowy chambers in which we occasionally spy blackened half-naked men slaving away in fiery pits or labouring over mysterious Victorian machines, the purpose and function of which remain obscure. Again, these sequences recall the lady in the radiator in Eraserhead but also the unnerving opening shot in Blue Velvet when Lynch shows us the subterranean horrors that lurk beneath the white picket fences and smiling firemen of small-town America.

One might argue that there was enough horror within damp, dank, smoke-filled squalor of industrial London, without the need for any further Gothic mystery – but it was growing anxiety about such urban nightmares that encouraged authors to use cities as their setting for ghastly tales. Eighteenth century Gothic stories contrasted the civilization of the city with the dangers of the countryside, a place under the sway of strange customs, primitive superstitions, lawless brigands and feudal tyranny, not to mention unmapped forests, inhospitable terrain and wild animals. Technological progress in the Victorian era may have brought a degree of enlightenment, but at what cost?

Near the beginning of the film, we see Dr Treves (Anthony Hopkins) operating on a man who has been injured in a machine accident – another sign that modern technologies brought new dangers as well as benefits. He remarks to his colleague that they will be seeing many more of these injuries in the future, one fatal drawback of machines being that ‘you can’t reason with them.’ There is a sense here that man is caught between two contrasting, inhuman threats: the irrationality of primitive nature (darkness, wild beasts, madness and the like) and the irrationality of modern technology. Despite his attempts to master them, ultimately he cannot claim to control either. Many of the classic Gothic tales contemporary with the period in which The Elephant Man is set – The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1885), The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) and Dracula (1897) blend modern science and the supernatural within contemporary urban settings. Darwinian theories about evolution may have seemed daringly progressive, but they were backward-looking too: for if modern man had evolved as part of a long and gradual process, then what distinguished him from animals was a matter of degree rather than a distinction in kind. Surely such a mutation could move in the opposite direction as well?

I wrote a little about Victorian freakshows in a previous post, and The Elephant Man makes the same point as I did: much as we like to distance ourselves from the insensitive vulgarity of those showground spectacles, modern media is not really that different in its commercialisation of all manner of forms of human tragedy, and we as audiences often share equal guilt in our consumption. In the film, Treves’ conscience begins to trouble him after visitors start flocking to see Merrick at the hospital: he recognises the truth of the accusation of hypocrisy made by Merrick’s previous ‘mentor’, the showman Bytes (Freddie Jones) – are not both men, in their own way, exploiting Merrick for their own ends?

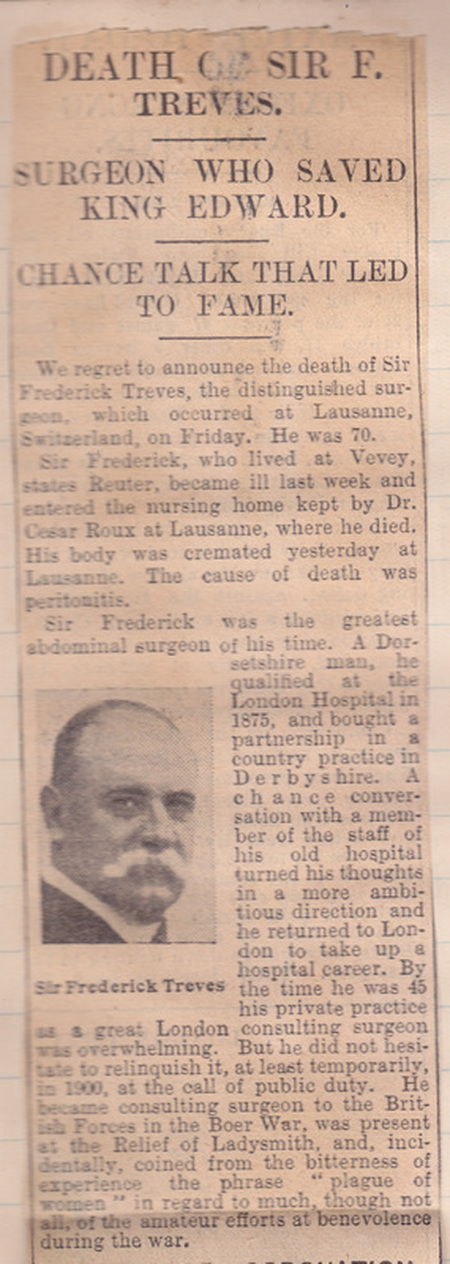

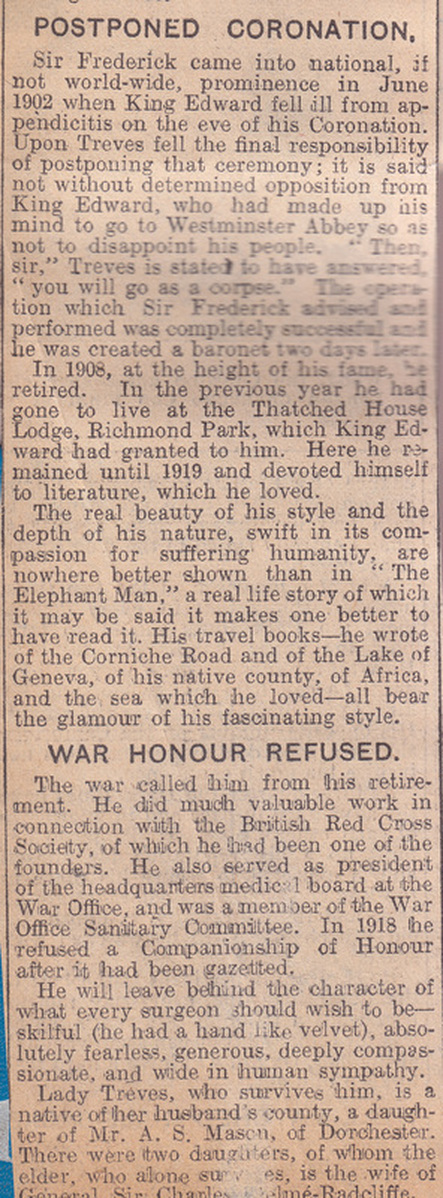

What sort of man was Treves? There is actually a copy of his December 1923 obituary in the scrapbook that I wrote about in last week’s blog post. Reference to ‘The Elephant Man’ appears in the second half of the tribute.