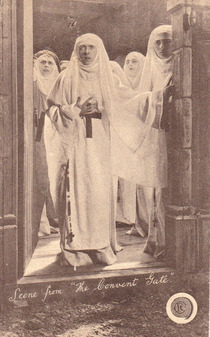

Following on from last month’s post about nuns photographs, I have looked out a postcard this time of a scene from the silent film The Convent Gate (1913.) This was directed by Wilfred Noy and adapted from a scenario written by Marchioness Townsend (1884-1959) that involved a jilted bride, insanity and a life-threatening blaze, in addition to the nunnery. In her autobiography It Was – and it Wasn’t (1937) the Marchioness revealed how the screenplay was developed with the help of a model theatre in her garden and cardboard cut-out nuns. Whether or not this led to two-dimensional characterisation, this postcard makes me sorry that The Convent Gate has not survived.

The film’s leading lady, Dorothy Bellew (right), was photographed by Bassano four years later – and she certainly does not look like a nun in this portrait.

This postcard shows a scene from The Monk and the Woman , which was released four years after The Convent Gate. On the left is Australian actress Maud Fane, playing Liane, a young French girl who finds shelter in a monastery while trying to escape the attentions of lecherous Prince de Montrale. The character on the right is young monk Brother Paul, played by Percy Marmont. Brother Paul has been given the job of watching over Liane, but (surprise!) ends up falling in love with her, leading him to clash with his abbot, the prince and the king….

Both the play and film caused controversy when released in Australia, being condemned by Archbishop Michael Kelly of Sydney. An austere prelate of puritan piety, Kelly remained at odds with the modern world all his life. He argued that The Monk and the Woman presented a distorted view of Catholicism that was offensive to the faithful; his views were supported by the Australian Catholic Federation, whose members boycotted screenings and applied pressure on advertisers to withdraw their custom. Critics, on the other hand, applauded the warmth and humanity shown in the film, as well as the performances by Fane and Marmont. Again, I’m disappointed to find that this film too is considered lost.

This is a still from Häxan: witchcraft through the ages (1922) an extraordinary silent film in seven chapters by Danish director Benjamin Christensen. Thankfully, this film has survived and is easily accessible on DVD: I’ve had the opportunity to watch it many times and it still retains the power to shock and mesmerize. Mixing documentary segments, slide lectures and dramatized horror sequences – including infanticide, witches’ sabbaths and the torture of suspected witches – the film has an avant-garde, surrealist feel that accentuates its nightmarish subject. Inevitably, however, this weakens Christensen’s rationalist argument: if his aim was to condemn medieval superstition and ignorance, why spend so much of the film experiencing false visions, and imbuing them with a power that only enhances viewers’ horrified fascination?

Anyway, even if we regret and abhor the cruelty of religious persecution, and the sufferings caused by ignorance, I doubt the sort of secular rationalism advocated by Christensen would really have helped matters in medieval Europe. Ninety years have passed since he made Häxan and aspects of his solution appear almost as dated as the medieval mindset he mocked. Christensen’s attempt to compare witch’s behaviour to that of hysterics treated by Professor Charcot (Chapter Seven) is one particularly unconvincing argument – Charcot’s category of ‘hysteria’ has now as much credibility as the demonic creatures depicted during the witches’ ritual in Häxan. Christensen can be forgiven for that, though, as he raises some challenging points about the misuse of power and shows real compassion for the unfortunate women, old and young, who became victims of witch trials.

The film is fairly anti-clerical throughout, portraying gross, lustful and gluttonous friars in addition to the cruel Inquisitors. A short sequence set in a convent shows the devil (played by Christensen himself) causing appearing to one of the nuns and inciting her to stab a consecrated host – an outrage that throws the rest of the community into a frenzy of writhing and, well, hysteria.