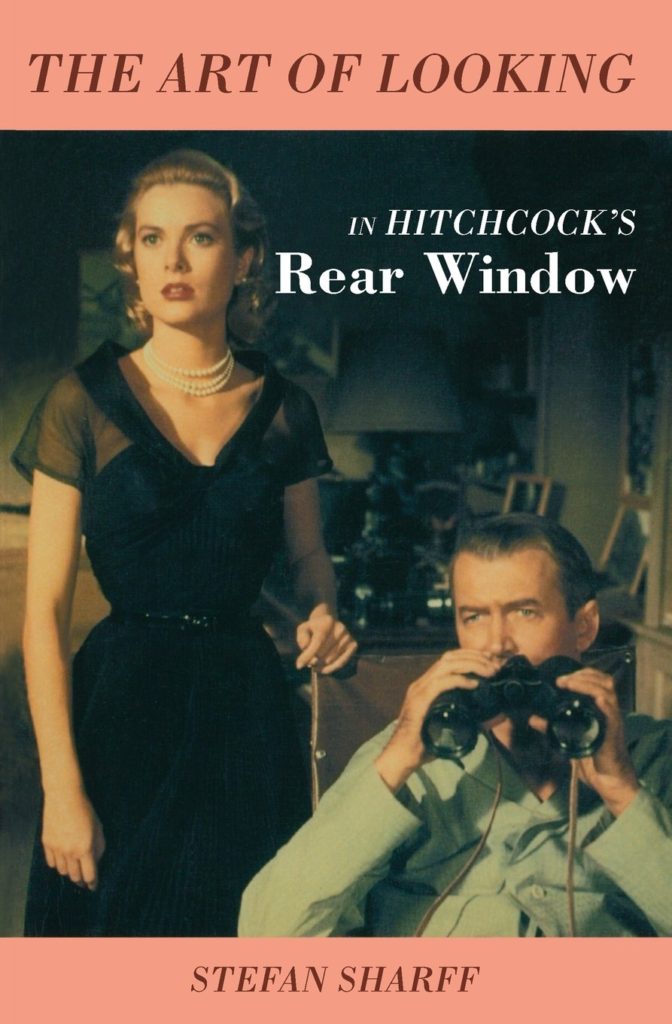

Sharff (1919-2003) was born in Poland, moving in 1939 to Moscow where he joined the Film School before being apprenticed to the director Sergei Eisenstein in Kazakshtan. He later moved to America where he worked as film-maker for the UN, continuing to make documentaries while teaching film at Columbia University. Here he wrote Elements of Cinema (Columbia University Press, 1982) and Alfred Hitchcock’s High Vernacular. Theory and Practice (Columbia University Press, 1991) which includes a shot by shot analysis of Notorious (1946), Family Plot (1976) and Frenzy (1972). This work has clearly laid the ground for The Art of Looking, in which Sharff devotes his attention exclusively to Rear Window with the aim of demonstrating that ‘cinema art can be depicted as a work composed, not unlike an orchestral piece of a large painting.’ He does so over five chapters, beginning an introduction ‘The Art of Seeing, the Art of Looking’, followed by Chapter 2’s ‘Rear Window’ which provides a synopsis of the story, an outline of Hitchcock’s approach to the film and the techniques he uses in Chapter 3’s ‘Bricks and Mortar’ (pp.22-101) followed by the heart of the book, Chapter 4. Shot by Shot, with Timing and Dialogue (pp.104-78) which provides a formal and technical scheme of the entire film, with an exhaustive description of all 796 shots in the film. Chapter 5 winds up with some ‘Concluding Remarks.’

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window

One of the interesting things to me about Sharff’s book is his argument that Rear Window ‘promotes the primacy of visual information and the merits of silent film’ (p.8). As he observes, almost 35% of the film is silent, without dialogue, and this is in keeping with a generally disparaging attitude towards dialogue in Hitchcock’s film and his desire to use visual language as the primary means of communicating plot and character. As Hitchcock remarked to Truffaut during their conversations in 1962, ‘dialogue should simply be a sound among other sounds, just something that comes out of the mouths of people whose eyes tell the story in visual terms’ (Hitchcock, by Francois Truffaut. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983. p.222.) This rather disparaging attitude towards film dialogue indicates that he regarded the real language of cinema as being primarily visual, and this underpins Sharff’s desire to reveal to readers the meticulous care with which Hitchcock crafted his visual imagery, presenting a shot-by-shot analysis that offers valuable insights into how Rear Window has been composed and edited.

Boris Rautenberg’s painstaking panoramic rendering of James Stewart’s view of his courtyard reiterates Sharff’s point – there’s a lot going on in this film.

Although the book is obviously a detailed and comprehensive analysis of the formal elements within the film, Sharff makes the case that Rear Window is really a form of metafiction, holding up a mirror to its viewers to challenge them about the whole process of cinema-going and the nature of looking, gazing, seeing what others see, what it means to watch and to be watched. While this is a concept that could be debated at length, perhaps the the most important thing one gains from reading The Art of Looking is a realisation of the masterful skill with which the film is constructed. Sharff’s comparisons of Hitchcock to an architect as well as a composer are well-founded, and his exhaustive frame-by-frame analysis drives home the extent to which the director crafted every single shot. It should be noted too that this was the first book to publish the entire script of the film, including all the dialogue.

Given that the book came out in the same year that commercial DVDs were launched, it is almost certain that Sharff watched Rear Window on VHS or 16mm, which means that this process of putting this book together must have been a painstaking – not to say tedious – matter. It also means that the quality of the still images reproduced here leaves much to be desired by today’s standards. However, the solution to this is obvious – go and watch the film again, which is no doubt what the author would like readers to do once they’ve read the book. Is that not what #ClassicFilmReading is all about?

This was another entry in the #ClassicFilmReading series for 2018