Monthly Archives: July 2016

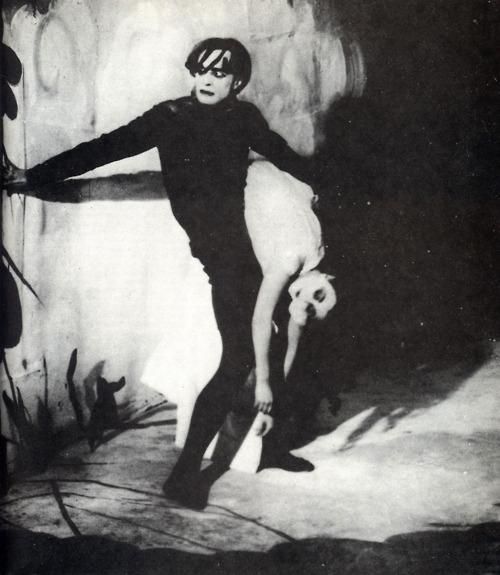

Walbrook’s Leading Ladies: Part Four – Lil Dagover

Starred with AW in Eine Frau die Weiss Was Sie Will (Victor Janson, 1934)

Her striking looks inspired Max Reinhardt to have her personify ‘Beauty’ at his new festival in Salzburg in 1925, a role she reprised for the next six years. Unlike many other silent actresses, she survived the transition to sound, and her acting skill probably benefited from her brief visit to Hollywood in 1931 to star in The Woman from Monte Carlo. She certainly appears more lively and natural in her performances after she returned to Germany, and this too is noticeable in her co-starring role with AW.

As it’s based on an operetta by Oscar Strauss, Eine Frau die weiss was sie will (Viktor Janson, 1934) has both a musical plot and plenty of musical numbers. Lil Dagover plays Mona Cavallini, an opera star who is much admired by the men, especially the debonair Axel Basse (AW, of course.) Unfortunately, he also has an admirer – the lovely young Karin (Maria Beling), daughter of stern industrialist Erik Mattisson (Anton Edthofer.) Entirely smitten with Anton (well, who wouldn’t be?), and frustrated at his infatuation with the opera singer, Karin asks her father to arrange for a meeting with Cavallini so that she can explain about her feelings. Her plan is successful – Cavallini spurns Axel’s advances and instead sends him in Karin’s direction, resulting in their marriage.

What Karin doesn’t know is that Cavallini is actually her mother, who left her husband and infant child many years earlier for a career in showbusiness and has been prevented by Mattisson from ever having contact with her daughter as a result. Matters become complicated when Karin learns that her husband has met Cavallini behind her back. Upset at the thought that he’s having an affair, she decides to get her revenge by having a fling with another man. Cavallini learns of her plan – but can she stop her daughter destroying her marriage? Will she reveal her identity to Karin? Things are resolved, as one would expect, with a great deal of light-hearted melodrama and singing.

A talented singer as well as actress, she did her own dubbing in foreign languages for multi-lingual releases, and worked with many of AW’s peers, such as Reinhold Schunzel for whom she played London fashion queen Jennifer Lawrence in Das Mädchen Irene (1936.) She was honoured as a Staatscchauspielerein (State Actress) by Goebbels for her role as the adultress Yelaina in Die Kreutzersonate (1937). and enjoyed a successful film career that continued throughout the post-war era and – like AW – led her onto German television in the 1960s.

Olivia de Havilland: ‘Lady in a Cage’ (1964)

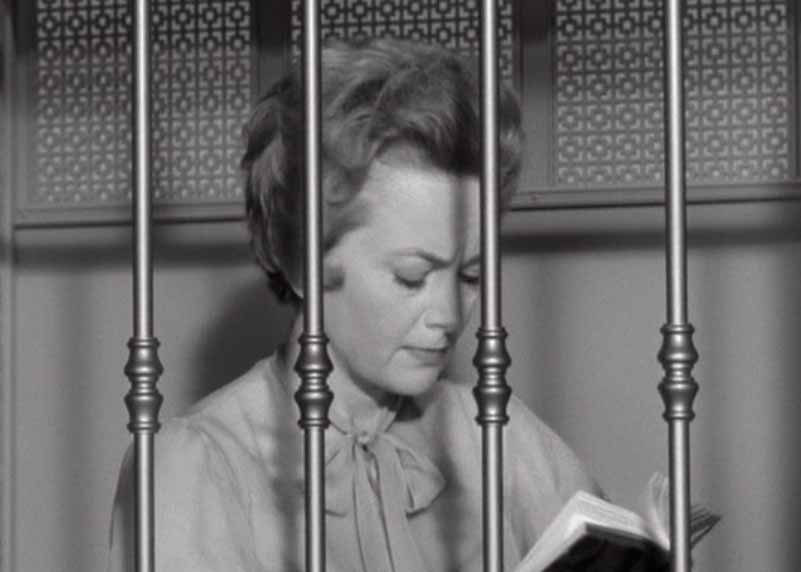

When did the ‘Sixties really begin? In terms of popular culture, there’s a good case to be made for 1964 – certainly in terms of music and moral attitudes, the spirit of the ‘Fifties did not disappear with the change of decade. However, there is a watershed moment that can be dated to 1960, and that was the transformative impact on cinema brought about by the release of two film – Peeping Tom in the UK and Psycho in the US. Both are superbly crafted yet disturbing movies that introduced audiences to a new form of horror, one that did not require actors to dress in scaly rubber suits or cardboard robot outfits in order to frighten. The monster now could be the neighbour next door, and film-makers began trying to terrify cinema-goers by suggesting that appalling events could take place in realistic, contemporary settings. Although Lady in a Cage is a very different film from either Psycho or Peeping Tom, it could not have been made without them, and its central image – that of the caged lady, trapped and exposed to view – can be regarded as a natural extension of the voyeurism and scopophilia inherent in those two movies.

It is a little unsettling, therefore, to realise that the lady in a cage is none other than Olivia de Havilland, an accomplished stage actress and one of the brightest stars of Hollywood’s ‘Golden Age’, who c0-starred with Errol Flynn in no less than eight movies and received her first Oscar nomination in 1940 for her role as Melanie in Gone with the Wind. That era seems far, far removed from the unsavoury urban modernity of Graumann’s 1964 movie: but might one regard Olivia’s performance as a link between them? What could such a distinguished actress bring to a role like this? Before trying to answer these questions, it is necessary to have a look at the film.

The opening credits can be seen as a nod to Hitchcock, with the Saul Bass-style title sequence evoking memories of Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959) and of course Psycho (1960), but these scenes also serve to warn us of what is to follow. Against a backdrop of discordant jazz – superbly scored by Paul Glass – and broken up by the modernist text of the titles, we witness a series of disturbing, fragmentary scenes of urban life: car traffic, blaring horns, a young coloured girl running roller skates up and down a man’s leg, a couple necking in their car while an agitated woman shouts on the radio about the need for an ‘anti-Satan missile’, firecrackers blowing the lids off dustbins and – most disturbing of all – a dead dog lying in the road as cars drive past: a cruel indictment of the uncaring nature of urban life, as well as a hint of how the film will end.

It is clear from this raucous clash of sounds and images that all is not well in society. Lady in a Cage was filmed not long after the assassination of JFK and is permeated by the anxieties of the age – about Russia and Communism, the breakdown of social norms and traditions, the rebelliousness of the younger generation, civil disorder and racial tension…it’s all here, simmering under the surface, made worse by the sweltering summer heat that practically drips off the screen. Our introduction to the main characters comes when the camera enters the house through the grille of an air vent – a voyeuristic point-of-view shot that neatly introduces the imagery of bars. The film’s first word is ‘Darling’ – written and spoken by Cornelia Hilyard’s son Malcolm (played by William Swan), whose intimate relationship with his mother brings back memories of Mrs Bates. He is shown writing a letter to his mother for her to read while he is away. Although it begins with intense affection, we glimpse the phrase ‘kill myself…I can’t go on’, and began to suspect that all is not well here. With an audaciousness ahead of its time, the film makes numerous allusions to incest and homosexuality and – just in case anyone had missed the hint – a graphic allusion to the fate of Oedipus in the final frames.

When Mrs Hilyard (Olivia de Havilland) appears, it is clear at once that she represents an earlier, more civilized era. De Havilland was 47 when this was filmed, yet her dress and demeanour suggest someone older, as does her reliance on a walking stick, even if this is because her character is recovering from a hip operation. This house is filled with fussy trinkets and ornaments, such as the Lowestoft porcelain vase she is holding above. We just know that this genteel little world is going to be shattered.

The storyline can be sketched out in a few sentences. As everyone heads out of Los Angeles for the weekend of 4th July, Mrs Hilyard is left stranded inside her home, trapped inside the elevator cage between floors when the power fails. This is caused by Malcolm’s car clipping the edge of a ladder as he drives away from the house; the ladder then falls against a power cable, tugging it away from the wires and breaking the connection. The fact that the ensuing series of tragic events has its origins in such a trivial and arbitrary occurrence underscores the chaotic, fragmented nature of the modern world. In the city, people can bring about each other’s undoing without being aware of the consequences of their actions, while – conversely – cries for help and alarm bells are heard but ignored by dozens of passersby: her attempts to ring the alarm for help only succeed in drawing the attention of a drunken hobo George (Jeff Corey), who proceeds to gain entry to the house and helps himself to drink and other items. George goes to tell his friend Sade, a blousy hustler (played sensitively by Ann Sothern) about the rich pickings available at the house, unaware that his sale of the stolen items at a pawn shop has been watched carefully by a trio of delinquent youngsters led by Randall (James Caan, in his first big film role.) This gang follows George back to the house, and proceed to wreak havoc, trashing the house and terrorising the helpless occupants.

Some viewers felt shock and disappointment that Olivia de Havilland would involve herself in a film like this, but anyone familiar with her career would be aware that she was no stranger to difficult material. In Dark Mirror (Siodmak, 1946) and Snake Pit (Litvak, 1948) her characters wrestled with mental illness, while more recent ventures such as Light in the Piazza (Green, 1962) and the Broadway hit Gift of Time dealt with mental disability and terminal illness respectively. For an actress willing to embrace roles such as these, the part of Mrs Hilyard presented the intriguing challenge of playing a woman confined in a small space for almost the entire film, deprived of opportunities for expressive movement or interaction with other actors.It is possible that these unusual elements of the role made it an attractive prospect for Olivia, but I’ve often felt that the title Lady in a Cage would be an apt description of the plight of many Hollywood actresses as they enter middle age. Studios tend to lose interest in their leading ladies as the years grow on, limiting the number and quality of the roles offered to them, narrowing their prospects, and forcing them to accept parts that would have been considered unworthy of their talent in a previous decade. In saying that, the early 1960s saw a series of films starring actresses from Hollywood’s Goolden Age, such as Bette Davis and Joan Crawford in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (Aldrich, 1962), Strait-Jacket (Castle, 1964 – written by Psycho‘s Robert Bloch) and Hush..Hush, Sweet Charlotte (Aldrich, 1964) which brought together Olivia de Havilland, Bette Davis and Agnes Moorhead. These films share many common themes and a web of personal connections, not least the fact that De Havilland replaced Joan Crawford in both Lady in a Cage and Hush..Hush, Sweet Charlotte. Where Lady in a Cage differs from these films is in its gritty urban realism and distinctive visual style.

The film’s reception, however, was far from enthusiastic. Following its American release on 10 June 1964, a critic in Time magazine waspishly claimed that the film ‘adds Olivia de Havilland to the list of cinema actresses who would apparently rather be freaks than be forgotten. (Time, 19th June) and others expressed disgust at what they regarded as ‘a sordid, if suspenseful, exercise in aimless brutality.’ (New York Times, 11th June.) The British Board of Film Classification refused to issue the film with a certificate, effectively preventing it from being seen by British audiences until it was released on video with an 18 certificate in 2000. When it came out on dvd five years later, it was reclassified as a 15. After forty years, audiences had become inured to scenes of wanton cruelty and sadism.

It could be argued that the film’s treatment of mindless violence prefigured the direction taken by many subsequent film-makers. When Randall tells George that the gang are going to kill everyone in the house, he asks ‘Why us, what have we done?’, to which the young man replies ‘You’re here.’ This exchange reappeared in another ‘home invasion’ movie, The Strangers (Bertino, 2008), which again features a trio of masked criminals, whose response to a similar question from frightened occupants was ‘Because you were home.’ Such an attitude reveals a total absence of moral conscience, and the somewhat laboured imagery of Lady in a Cage indicates that the film was playing on genuine fears at this time that the age of moral certainties and social cohesion was under siege, facing the same level of threat as Mrs Hilyard. It is, however, far from clear what we are meant to learn from her response about any possible solution to society’s problems. Her final realisation ‘It’s all true, I’m a monster’ is followed by her anguished cries at Elaine and Essie as they try to flee the scene – ‘Murderers, monsters!’ – suggesting that she has sunk to their level.

She has lost her son and her precious belongings, but worse still, she has lost the moral dignity that set her apart from the iconoclastic youths. If she has gained anything, it is a degree of insight into her own character flaws, an awareness of her previous indifference to the sufferings of others, and the appalling effect that her suffocating love has had on her son.