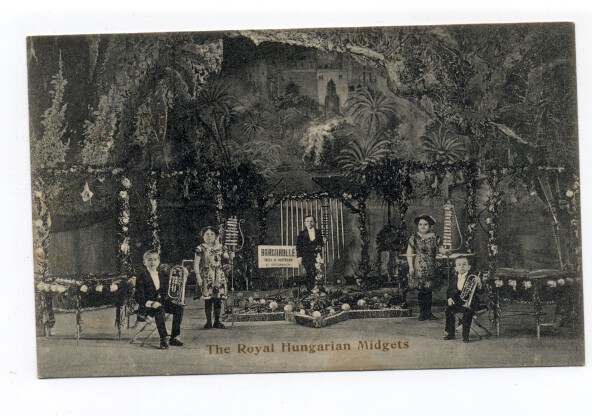

Postcard #1

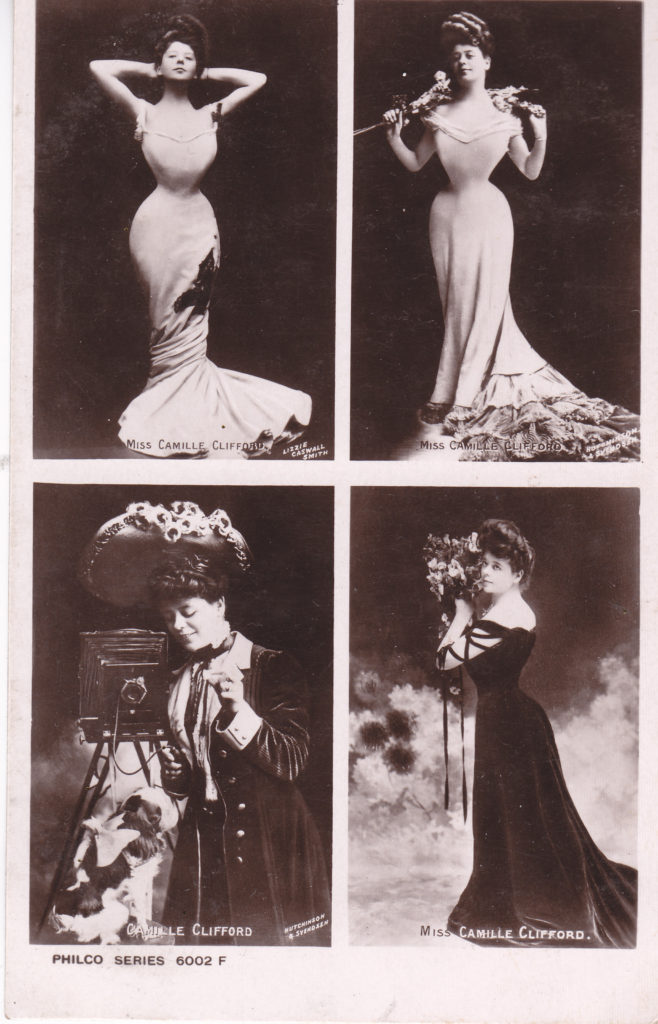

I’m always drawn to postcards showing old cameras or photography, and it was the image above that got me collecting postcards of Belgian-born theatre star Camille Clifford. Her acting career was brief – barely four years (1902-6) – and it was her association with the popular ‘Gibson Girl’ image that made her famous.

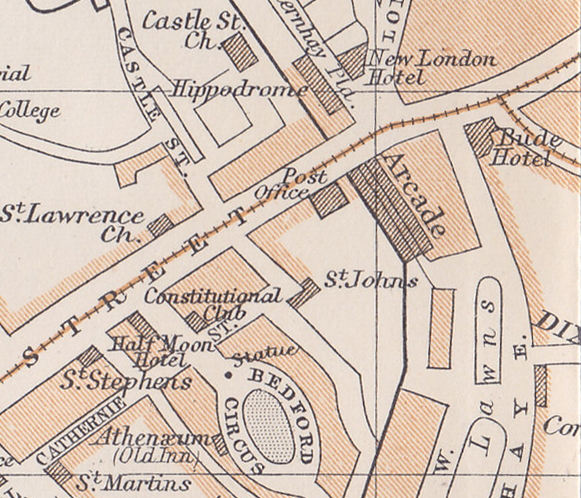

In the 1890s, sketches of young women by Charles Dana Gibson began appearing in periodicals such as Harper’s Weekly, Life and Scribner’s, creating an instantly-recognizable image that was replicated in advertising, postcards, modelling illustrations and other merchandise. The ‘Gibson Girl’ look combined bouffant hair, a curvaceous figure, delicate facial features and fashionable clothes, as well as a streak of independence and confidence that resonated well with the emergence of the ‘New Woman’ and the Suffrage movement. The look was said to have been inspired partly by Evelyn Nesbit (below) and Gibson’s wife Irene Langhorne.

Evelyn Nesbit, photographed in 1903 by Gertrude Kasebier

Sketch by Charles Dana Gibson, showing the characteristic ‘bouffant’ hairstyle. As well as being elegant and voluptuous, the ‘Gibson Girls’ suggested intelligence, spirited independence and a degree of emancipation – an idealised (and non-threatening) version of the New Woman

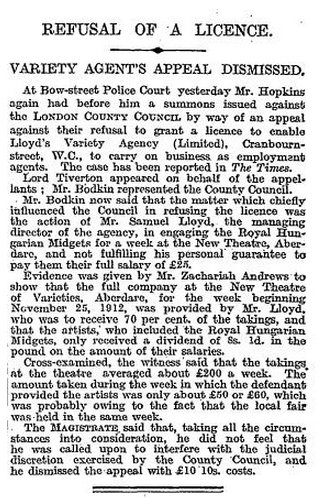

In 1905 Camille won a modelling competition held to find the perfect embodiment of the Gibson Girl, and images of her quickly began to be published in fashion and society magazines. Many of these photographs were taken by Lizzie Caswall Smith (1870-1958.) The pictures below show off her hourglass figure, which boasted an 18″ wasp waist.

Postcard #2

Despite the British-sounding surname, Camille was born in Belgium in 1885 to Reynold Clifford and Matilda Ottersen. After the death of her parents she was raised by relatives in Scandinavia before moving to America where she lived in Boston. She made her stage debut in 1902 and travelled to England two years later with Col. Henry Savage’s theatre company, performing a minor role in their musical comedy The Prince of Pilsen. When the rest of the cast returned to America, she remained behind, obtaining the part of Sylvia Gibson in Seymour Hicks’ play The Catch of the Season.

Postcard #3

This postcard shows Camille with her fiance, Captain the Hon. Henry Lyndhurst Bruce, eldest son of the 2nd Baron Aberdare. Their engagement was announced at the end of August 1906 and they were married at Hanover Square Registry Office in London on 11 October 1906. The above photograph, therefore, was probably taken in September 1906. It was a busy time for Camille, who was now playing the Duchess of Dunmow in the musical comedy The Belle of Mayfair at London’s Vaudeville Theatre. Everyone knew that she was cast for her beauty rather than her musical talent, and her voice – even thinner than her waist – was barely adequate for her number ‘I’m a Duchess’, even after receiving singing lessons from Ivor Novello’s mother, Madame Clara Novello Davies. As one theatre critic put it, ‘The voice of Camille Clifford is not strong, but she wears such beautifully cut clothes and moves so elegantly up and down the stage that her turns is sure to be popular.’ [The Times, 12 April 1906, p.6.] And it was: audiences flocked to see her in the show nonetheless, including many wealthy male admirers such as Lord Aberdare’s son. After their engagement, Camille was going to resign from the show, but the producers enticed her to remain by offering her greater publicity and another musical number – a song entitled ‘Why do they Call Me a Gibson Girl?’

I walked one day

Along Broadway

When I was in New York.

And friend of mine

Said “My, you’re fine!

You have got the Gibson walk!

You have the pose

And Gibson nose

And quite the Gibson leer.

You’ve surely heard of the man called Gibson.”

(He meant the fellow called Dana Gibson.)

What he meant was not quite clear

Until I landed over here.

But why do they call me a Gibson Girl? (Gibson Girl?) Gibson Girl!

What is the matter with Mister Ibsen? (Mister Ibsen?) Why Dana Gibson?

Wear a black expression and a monumental curl,

And walk with a bend in your back,

Then they call you a Gibson Girl.

Just walk round town,

Look up and down:

The girls affect a style

As they pass by,

With dreamy eye,

Or a bored and languid smile.

They look as if

They had a tiff

With Hicks or Beerbohm Tree;

They do their best, for they’ve seen the pictures.

(They’ve missed the point of the Dana pictures.)

They’re intended, don’t you see,

For all a perfect type to be.

But why do they call me a Gibson Girl? (Gibson Girl?) Gibson Girl!

What is the matter with Mister Ibsen? (Mister Ibsen?) Why Dana Gibson?

Wear a black expression and a monumental curl,

And walk with a bend in your back,

Then they call you a Gibson Girl.

The Hon. Henry Lyndhurst Bruce served as a Captain in the Royal Scots Regiment. They had one child, Margaret, who was born in August 1909 but only lived a few days. Captain Bruce was killed in action at Ypres in December 1914. She married her second husband, Captain (later Brigadier) John Meredyth Jones Evans in 1917 and retired from acting after the war. She took up golf and competed in the game at a high level, but by the late 1920s was better known for running a successful stable of racehorses. Their names became familiar at racing events over the next three decades – Alliteration, Claudine, County Guy, Exemplary, Grass Court, Holyrood, Longstone (winner of the Newbury Cup in June 1955), Misty Cloud, Puissant, Rackstraw and Sidi Gaba, to name a few. She devoted considerable sums of money on building up a strong stable: sometimes she was able to pick up a promising horse for a few hundred guineas, but in 1938 she paid 6,500 guineas for Royal Mail, who had won the previous year’s Grand National. Alas, the horse proved unable to repeat his success at Aintree, although he did go on to win a few cups at Cheltenham in the 1940s. Camille caused a further stir in 1949 by paying 17,000 guineas for two year old Hedgerow. Her husband died in 1957, fourteen years before Camille, who passed away on 28 June 1971.

style

style