To mark today’s screening of Black Narcissus as part of the series of Exeter Screen Talks, I wanted to celebrate twenty films about convent life. The emphasis is on movies that make some serious attempt at portraying religious life, and I have therefore ignored those with fake nuns (A Mule for Sister Sarah (1970) and Più forte sorelle (Renzo Spaziani, 1973) as well as the more lurid examples of the nunsploitation genre (Behind Convent Walls (1978), Sacred Flesh (1999) etc) but at the end of the day the selection is a personal one and is as arbitrary and subjective as can be.

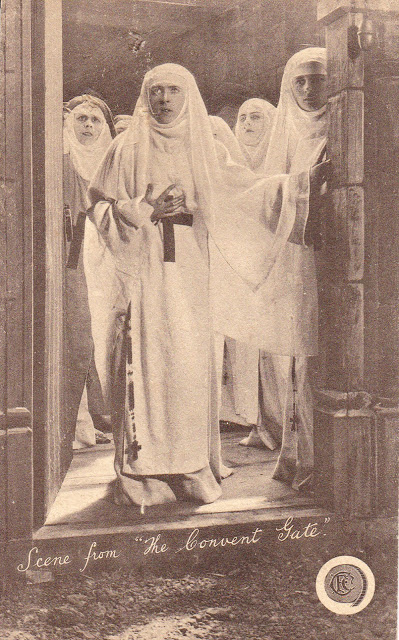

The Convent Gate (Wilfrid Noy, 1913)

Straightaway I’m cheating by writing about a film that I haven’t seen. It’s been estimated that between 75-90% of silent films were destroyed or disappeared, and sadly The Convent Gate was one of them. My interest was piqued when I came across this postcard at a flea market some years ago, and I wrote a little bit about it in a previous post.

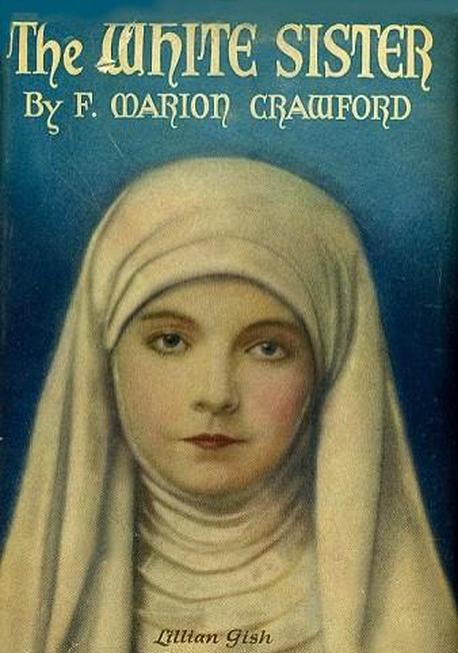

Ten years later Lilian Gish starred in this adaptation of F. Marion Crawford’s 1909 novel The White Sister. It had been filmed already in 1915 with Viola Allen in the title role, as star-crossed Italian lover Angela Chiaromonte who enters religious life after a series of tragic events, plotting and misunderstandings. Ronald Colman played her lover, Captain Giovanni Severini.

The story is set in Italy and ends with the climactic eruption of Vesuvius. While in Sorrento five years ago I came across a street named after Crawford – he moved here in the 1880s and knew the area well.

The White Sister (Victor Fleming, 1933)

In the third screen adaptation of Crawford’s novel Angela was played by Helen Hayes, who was about to make her name playing Mary Queen of Scots and Queen Victoria on Broadway. Colman’s role was taken here by Clark Gable.

Les Anges du Péché (Robert Bresson, 1943)Comparisons are often drawn between the work of Bresson and Bill Douglas, both of whom excelled in the use of poetic imagery with minimal dialogue. Bresson was still finding his style with Les Anges du Péché, his first feature film, made in wartime France in collaboration with Dominican friar Fr. Raymond Bruckberger O.P. and playwright Jean Giraudoux. ‘Angels of Sin’ follows events in a religious community dedicated to rehabilitating women prisoners, but it is easy to see the German occupation of France as influencing the themes of incarceration and vengeance killing.

Bells of Saint Mary’s (Leo McCarey, 1945)

Ingrid Bergman and Bing Crosby star in this drama as Sister Mary Benedict and Father Charles O’ Malley, fighting to save their city school from closure. Both of them get to sing in the movie of course, Bergman singing the traditional Swedish folksong Varvindar Friska (Spring Breezes) and Crosby crooning the title song (along with a choir of nuns) and others. The movie is used in the film The Magdalene Sisters (Peter Mullan, 2002) with bitter irony – the sweet nuns of the 1945 film contrasting harshly with the cruel, somewhat cartoonish villains of Mullan’s tale.

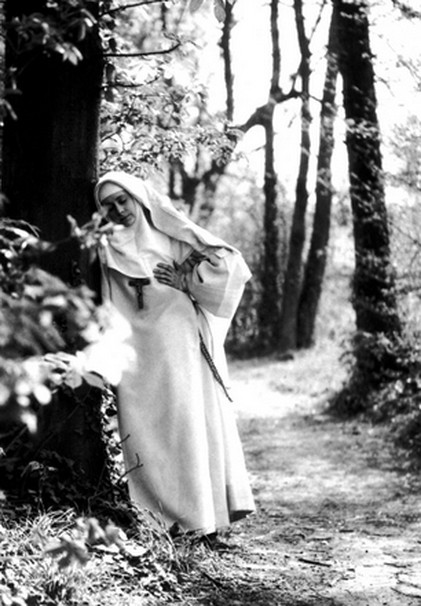

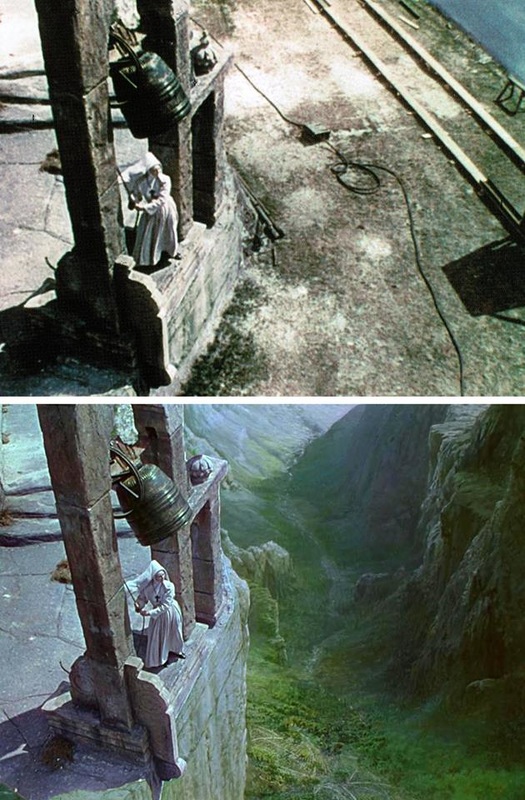

One of my favourite films of all time, and my strongest recommendation of all those listed here, Black Narcissus is based on Rumer Godden’s 1939 novel and tells the story of a community of nuns opening a convent in the Indian Himalayas. As with so much of Powell and Pressburger’s work, the film is imbued with a strong sense of place and an awareness of the effect of location on human behaviour: the lush sensuality of the landscape (filmed in vibrant Technicolor by Jack Cardiff) and the erotic history of the convent building (a former seraglio) seem to draw out the emotional tensions and desires of the nuns – in particular Sister Ruth (below.)

The magnificent cast also includes Deborah Kerr, Flora Robson, Jean Simmons, Esmond Knight and a surly, swaggering David Farrar.

Another tale of nuns moving into an unfamiliar location, but very different in tone, Come to the Stable starred Loretta Young and Celeste Holm as two French nuns trying to establish a foundation in Bethlehem, Connecticut. Unlike the plot of The Bells of St Mary’s the nuns don’t resort to trickery to achieve their goals…

Thunder on the Hill (Douglas Sirk, 1951)

This who-dunnit is set in a storm-lashed Norfolk convent, where convicted murderess Valerie Carns (Ann Blythe) gets marooned by the weather while en route to the gallows. (Ruth Ellis, the last woman hanged in Britain, died four years later, in 1955.) Claudette Colbert plays Sister Mary, a young nun who begins to have doubts about Valerie’s guilt – setting her on course to clash with the Mother Superior (Gladys Cooper.)

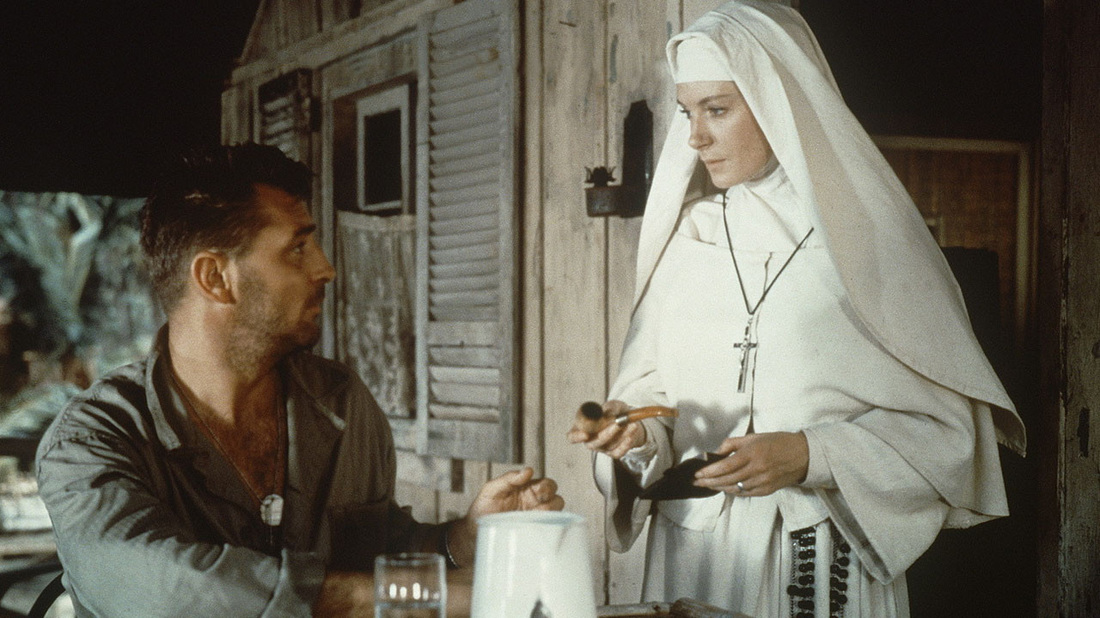

Heaven Knows, Mr Allison (John Huston, 1957)

Having played the Sister Superior in Black Narcissus, Deborah Kerr was demoted to the status of a novice in this film, in which she is stranded together with US marine Robert Mitchum on a Pacific island during WWII. They have to deal with lack of food, fever, Japanese soldiers and – of course – each other, while waiting to be rescued. Both stars give tremendous performances, while the exotic location (much of it was filmed in Tobago) provides a lush backdrop to the poignancy and drama of their situation.

The Nun’s Story (Fred Zinnemann, 1959)

Based on Kathryn Hulme’s 1956 novel, The Nun’s Story follows Sister Luke (Audrey Hepburn) as she struggles to deal with inner conflict as a medical nun working in Africa. As with The White Sister and Black Narcissus, there are hints of an unresolved romance haunting her decision to enter the convent, but Sister Luke also has to deal with issues regarding obedience and her duties towards her family and homeland after the Nazis invade Belgium while she is working in Africa. It’s one of the best films for a serious exploration of the real issues involved in taking the veil.

(Philippe Agostini, 1960) This was another wartime project of Fr Bruckberger O.P., based on Gertrud le Fort’s novel about a community of Carmelite nuns who were martyred at Compiegne in 1789 during the French Revolution. George Bernanos wrote additional dialogue – much of which was later dropped – and stage and opera versions were produced before the screenplay finally made it to the screen. Jeanne Moreau played Mère Marie de l’Incarnation.

(Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1961) Based on the same story about the possessed nuns of Loudun that inspired Ken Russell’s film ten years later, Mother Joan of the Angels is much less well known: this is a shame, as it’s an absolute masterpiece, subtle in all the places where Russell is extravagant, yet containing a wealth of stark, stunning imagery and poetic visuals.

Lilies of the Field (Ralph Nelson, 1963)

This film provided Sidney Poitier with his first Oscar, playing wandering handyman Homer Smith who finds work (but no wages) helping out a struggling community of nuns from German and Eastern Europe. The title of the film is taken from Matthew 6:28-30, which Mother Maria (Lilia Skala) quotes in response to Homer’s request to be paid.

Maria von Trapp’s memoir The Story of the Trapp Family Singers provided the basis for a Rodgers & Hammerstein musical which was in turn adapted for the screen by 20th Century Fox. Julie Andrews played Maria, a novice nun who leaves the convent for a while to work as a governess to an Austrian family of seven children, and ends up leaving religious life and marrying their widowed father. Some of the exterior scenes were shot at the convent of Nonnberg in Salzburg.

The Nun (Jacques Rivette, 1966)

Denis Diderot’s novel La Religieuse, published in 1796, offers a profound critique not only of religious life and Catholicism but also of the constraints placed upon women in 18th century society. Diderot’s simple tale recounts the sufferings of a young girl, Suzanne Simonin, who is forced into the convent by her family. French New Wave director Jacques Rivette adapted the novel for the stage before revising it for the screen, in both versions casting Jean Luc Godard’s then-wife Anna Karina as Suzanne. It remains quite stagey, with its slow pace and unadorned style, but it’s deeply moving and heartbreaking in its depiction of Suzanne’s ordeals as she experiences religious life under three Mother Superiors – the kindly Madame de Moni (Micheline Presle), cruel Sister Sainte-Christine (Francine Berge) and the ardent Madame de Chelles (Liselotte Pulver.) The film was remade by Guillaume Nicloux in 2013 with Isabelle Huppert playing Suzanne.

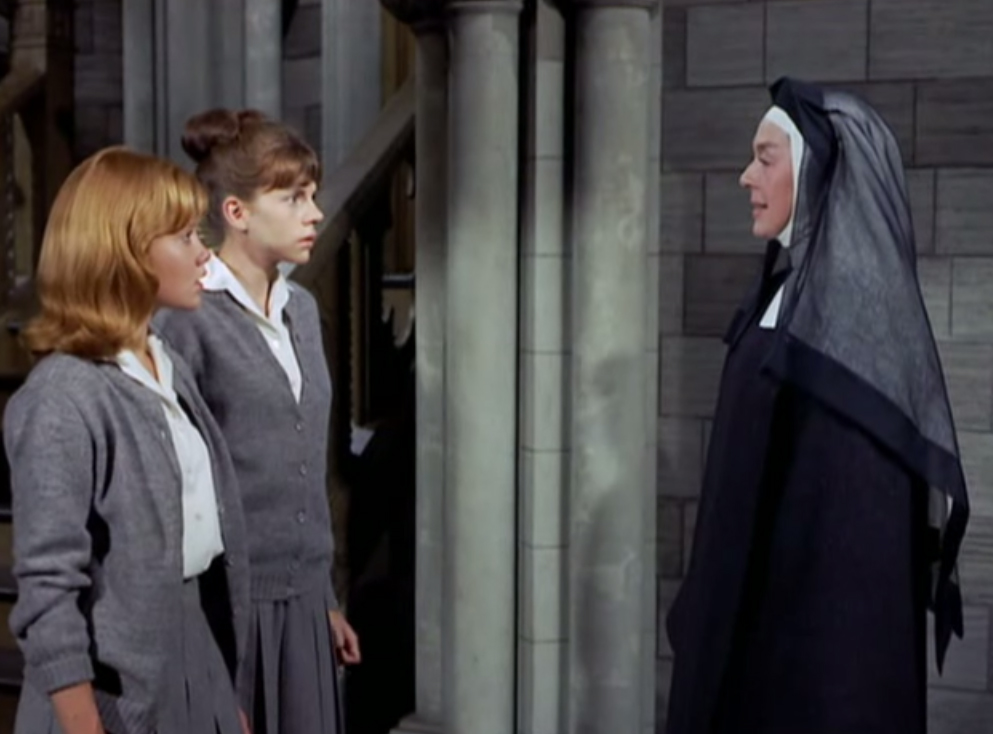

The Trouble with Angels (Ida Lupino, 1966)

Returning to the present day and a lighter vein, The Trouble with Angels was set in an American convent school where rebellious pupils Hayley Mills and June Harding try to outwit the Mother Superior (Rosalind Russell), only to find that they underestimate the nun’s wisdom and wiles. The success of the film inspired a rather lacklustre sequel, Where Angels Go, Trouble Follows (James Neilson, 1968.)

‘The Singing Nun’ was the popular name given to Sister Luc-Gabrielle O.P., also known as Jeanne Deckers (1933-85), a Dominican nun from Belgium who released several records including the No.1 single ‘Dominique’ (1963.) The movie is a sweetly fictionalised portrait of Deckers, whose life subsequently took a tragic dive downwards into depression, drug abuse and suicide.

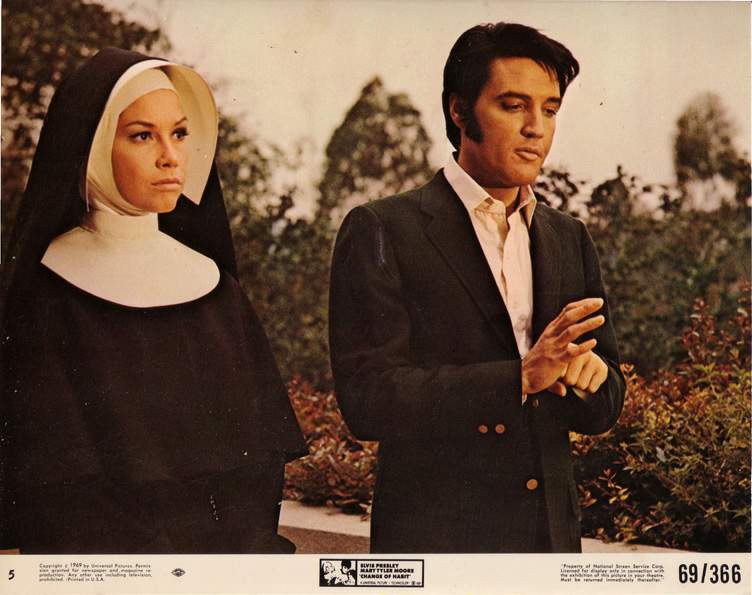

Change of Habit (William Graham, 1969)

Elvis Presley’s final fictional movie role saw him play a doctor in a run-down area who is unaware that three co-workers – Michelle Gallagher (Mary Tyler Moore), Irene (Barbara McNair) and Barbara (Jane Elliott) are in fact nuns who have shed their habits in order to gain the trust of the parishioners they are trying to help. The movie, as one would expect, contains romantic entanglements and lots of Elvis songs.

As a by-the-by, it is perhaps worth mentioning that another of Elvis Presley’s co-stars, Dolores Hart – who played opposite ‘The King’ in Lovin’ You (1957) and King Creole (1958) – entered a real-life convent in 1963 and later became the Prioress of Regina Laudis Priory in Connecticut.

The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971)

It’s been over forty years since the release of The Devils but Ken Russell’s extraordinary and disturbing work has retained its reputation as one of the most shocking movies ever made in Britain. The scenes of orgiastic violence are graphic and unrelenting, but shot with the high command of visual aesthetics that one would expect from production designer Derek Jarman. Although Vanessa Redgrave played Mother Jeanne of the Angels, the role had been originally offered to Glenda Jackson. However, after playing the female leads in Russell’s Women in Love (1969) and The Music Lovers (1970), a third erotically-charged performance might have been excessive (even for them.) As a representation of convent life The Devils cannot evade the charge of sensationalism – it’s a orgy of Grand Guignol grotesquerie and Gothic horror – but it explores aspects of religious psychology and the interior life that are barely touched by the other films listed here. Go there if you dare.

Nasty Habits (Michael Lindsay-Hogg, 1977)

It wasn’t long Jackson got another chance at playing a nun, and this time she accepted the offer: Nasty Habits is based on Muriel Spark’s novel The Abbess of Crewe: A Modern Morality Tale (1974), which took the then highly-topical story of the Watergate scandal (1972-74) and transposed its component parts into a Benedictine convent where a power-hungry nun is plotting to fix her election as abbess. The film version shifts the setting from Crewe to Philadelphia and assembled a star-studded cast that included Edith Evans as the old Abbess Hildegard whose death leaves a power-vacuum, Glenda Jackson as the ambitious Sister Alexandra (i.e. Nixon) and Geraldine Page and Anne Jackson as her accomplices Sisters Walburga and Mildred, who break into the sewing basket of her rival Sister Felicity (Susan Penhaligon) in order to steal a cache of love letters. Allegations of bugging and bribery lead to Vatican involvement, and those familiar with the Watergate story will enjoy identifying the characters and events being parodied.