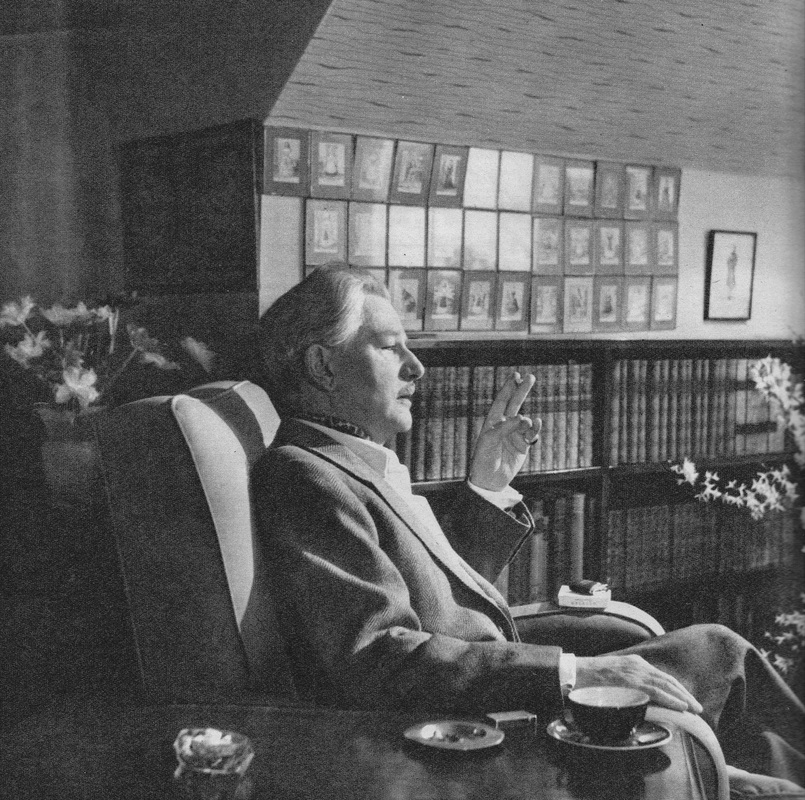

This is the first in a series of blog posts looking at some of the actresses who appeared onscreen with Anton Walbrook. As the title ‘Leading Ladies’ suggests, the focus is on those who played opposite AW after he established himself as a romantic lead: this will not be an exhaustive list of every actress who appeared in his films, and I’ve chosen to limit the scope to his sound films. In future blog posts I may return to some of the lesser known figures. As usual, the illustrations are taken from my own postcards, film stills and cinema programmes.

Anna Sten (1908-93)

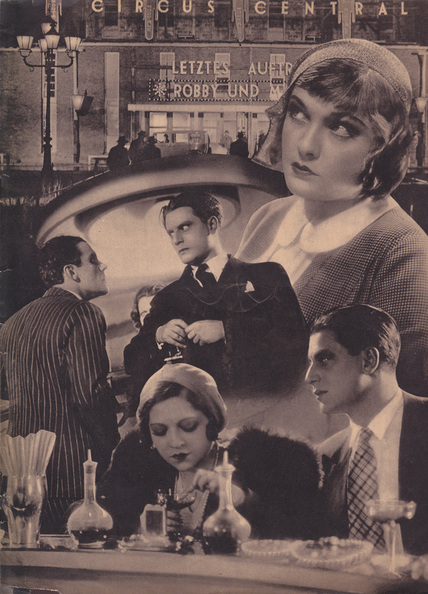

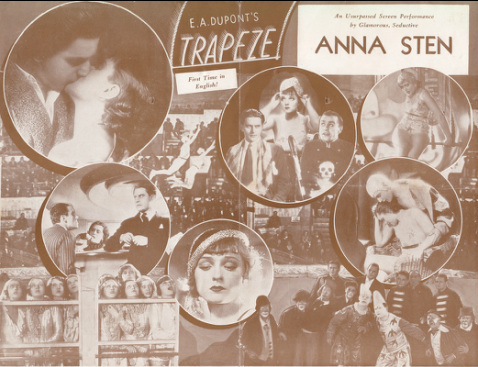

Starred with AW in his first sound film, Salto Mortale (1931).

Born Anjushka Stenski Sujakevich to a Ukrainian father and Swedish mother, Anna trained at the Moscow Film Academy after being spotted on stage in her hometown of Kiev by Konstantin Stanislavsky, creator of the famous school of method acting.

Like Anny Ondra (of whom more below), she had a short-lived marriage to a director – Fyodor Otsep – in whose films she appeared. After her husband cast her in Der Mörder Dmitri Karamazov (1931), she came to the attention of Sam Goldwyn who brought her over to Hollywood and spent the next two years trying, without success, to launch her as the new Garbo. Cole Porter gently mocked their endeavours in his 1934 musical Anything Goes:

‘If Sam Goldwyn can with great conviction

Instruct Anna Sten in diction

Then Anna shows

Anything goes.’

Just prior to this, Anna appeared in a number of Franco-German collaborations, of which Salto Mortale was one. French and German language versions of the film were shot simultaneously, with Sten, AW and Reinhold Berndt in the latter, playing three circus performers caught in a love triangle: Robby (AW) and Jim (Berndt) are friends who feed the lions and tigers, but who find themselves competing for the love of Russian stunt rider Marina (Sten.) When the circus launches a new attraction involving a highly dangerous trapeze act – the ‘Salto Mortale’ or ‘Leap of Death’ – Jim and Marina become partners on the trapeze while Robby operates the controls below. After a tragic accident leaves Jim with a damaged leg and unable to perform, he marries Marina, while Robby takes his place on the trapeze. Their deepening relationship places them in grave danger, for their lives depend on Jim releasing the trapeze with split second precision. As Jim sinks into drunken bitterness and jealousy, the stage is set for one final tragedy….

Camilla Horn (1903-96)

Starred with AW in Die Funf Verfluchten Gentlemen (1932)

Born in Frankfurt-am-Main, Camilla began her career as a dancer and cabaret performer in Berlin, having studied acting under another of AW’s co-stars, Lucie Höflich, whom I will write about in another blog. One of her earliest screen appearances was as an uncredited dancer in the 1925 celebration of the human body, Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit (Ways to Strength and Beauty.) She was working as an extra at UFA the following year when director F W Murnau chose her for the role of Gretchen in Faust. Recognised now as one the great masterpieces of silent cinema, Faust was an extravagant production filmed over six months at a cost of 2 million marks; it won Murnau a contract in Hollywood and launched Horn’s career. She made a few silent films in Germany before following Murnau to Hollywood. Although Joseph Schenk cast her in two United Artists films opposite John Barrymore, her Hollywood career did not live up to expectations and she returned to Europe, making several films in Germany in the early 1930s.

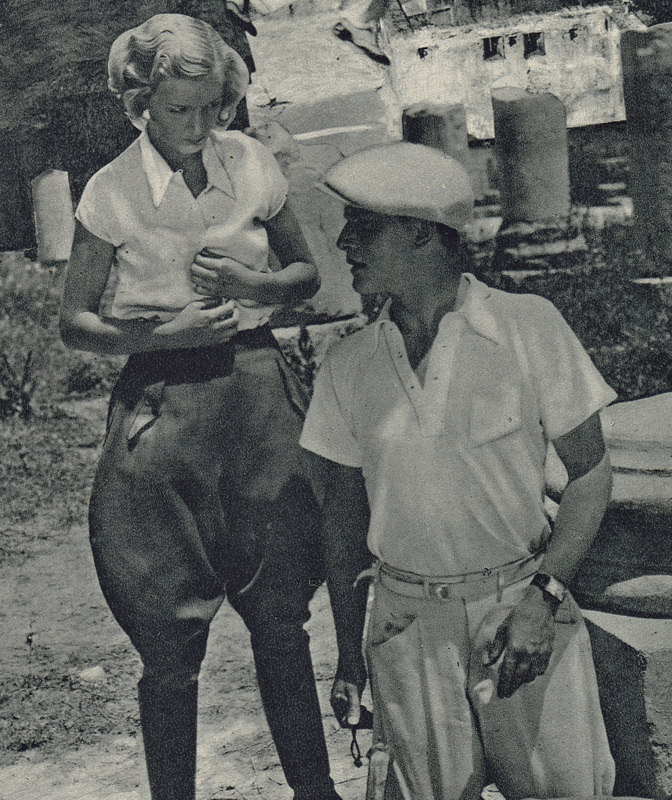

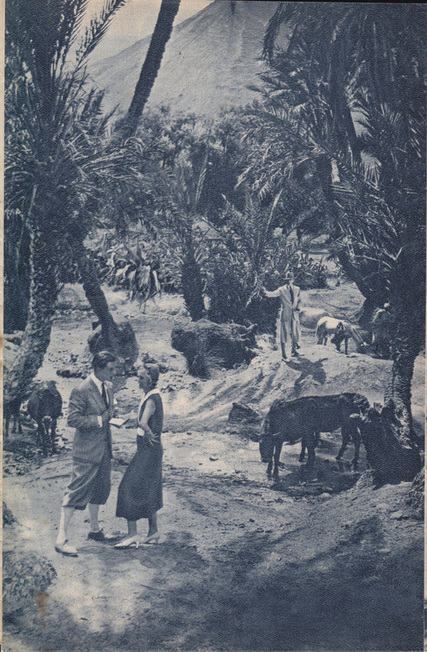

Die fünf verfluchten Gentlemen (The Five Cursed Gentlemen) was directed by Julien Duvivier, who simultaneously filmed a French-language version: neither AW nor Camilla Horn appeared in Les Cinq gentlemen maudits although other cast members such as Allan Durant, George Péclet and Marc Dantzer were in both. The story begins with German millionaire Alexander Petersen (AW) and Camilla (Horn) on board a ship to Tangiers. She is travelling to visit her uncle Marouvelle at his farm near Fez. Petersen falls for Camilla, and is invited to spend a few days at her uncle’s farm along with two English passengers, Midlock (Allan Durant) and Strawber (Jack Trevor.) On the way there they visit the ruins at Moulay-Idriss, where the Englishmen meet two friends, pilot Lawson and racing driver Woodland.After one of the men tries to remove a beggar girl’s veil, her father – revealed now as a sorcerer – utters a curse upon the group: before the next full moon, all five will die, with Petersen being the last. It doesn’t take long before the curse starts to be fulfilled – Midlock falls off a roof, Woodland dies in a plane crash and Lawson is found stabbed…but is everything what it seems?

Camilla Horn did not star in any other AW movies after this, but she worked with many of his co-stars and colleagues and remained in Germany during World War Two. Distancing herself from the Nazi regime, she fell into disfavour and was prosecuted by the Gestapo for a minor financial offence. She struggled to find work in Germany under the Nazis, but despite a disappointing postwar career, she made something of a comeback later in life with Schloss Königswald (1988) alongside other actresses of her era such as Marianne Hoppe and Marika Rökk.

AW and Duvivier were, of course, reunited twenty years after this film in the dark, expressionistic L’affaire Maurizius (1954.)

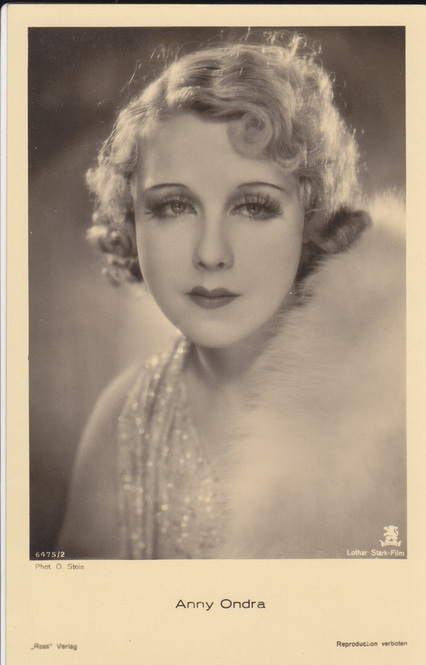

Anny Ondra (1902-87)

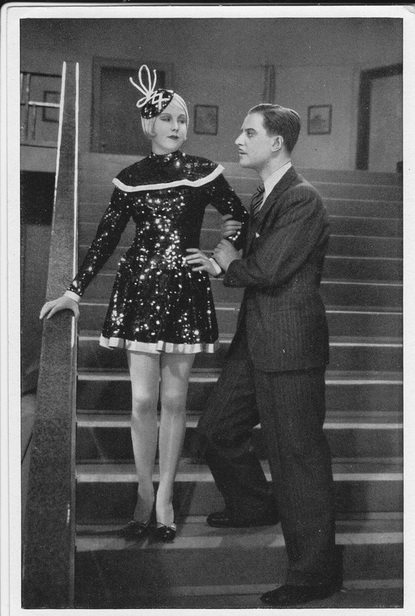

Starred with AW in Baby (1932) and Die vertauschte Braut (1934)

Anna Sophie Ondráková was born in Tarnów, near Galicia, and brought up in Prague where she began acting after leaving school. She came to the attention of actor-director Karl Lamac, who featured her in several of his silent films in the 1920s and eventually married her. In addition to her smouldering beauty, she proved herself a skilled and subtle actress, and it was not long before she became a huge star in Czech, French, Austrian and German films. Like AW, her career transcended national boundaries.

Anny’s name was familiar to British audiences through working with directors Graham Cutts and Alfred Hitchcock, who cast her as Alice White in his first sound film, Blackmail, in 1929. Her thick accent required dubbing by an English actress, and realising that a career in British films was now closed to her, Anny settled in Germany and founded the Ondra-Lamac-Film company with her husband in 1930; the business lasted six years, continuing after she divorced Lamac and married champion boxer Max Schmeling in 1933. Both Baby (1932) and Die vertauschte Braut (1934) were produced by Ondra-Lamac Film.

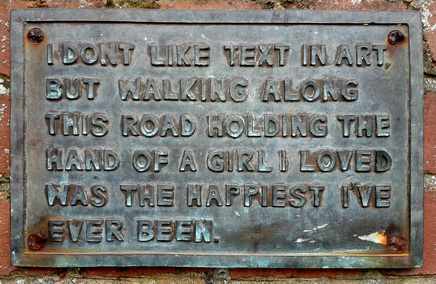

Another scene from ‘Die vertauschte Braut’

Another scene from ‘Die vertauschte Braut’

Anny used her body to great effect in her performances – not simply in showing off her legs (as above), although she did a lot of that – but also in skilled slapstick and physical comedy. There’s an amusing scene in Baby where she gets drunk and falls all over the room, in a performance that rivals that of Keaton or Chaplin. She plays a French heiress in the film, who meets two English aristocrats – Lord Cecil (AW) and Lord James (Willy Stettner) – while travelling to boarding school in England with her friend Susette. Things get complicated as the friends pretend to be showgirls, swap identities, join a (real) singing group called ‘The Singing Babies’ and get caught up in various escapades involving cross-dressing and an excess of drink! It’s great fun, and AW even gets to show off his juggling skills.

***

Still to come – Liane Haid, Luise Ulrich, Olga Tschechowa, Lil Dagover, Renate Müller, Paula Wessely, Anna Neagle, Diane Wynyard, Danielle Darrieux, Martine Carol and many more……