Tauber was born in Linz to theatrical parents, and began performing professionally in his early twenties. After the end of World War One his career really took off, with a contract to the Vienna State Opera, the first of over 700 recordings, and hugely successful excursions into the popular genre of operetta. His first film appearances were during the silent era, but with the advent of sound there was clear potential for adapting his operetta performances for the screen.

Many of these films were, to be frank, of no great merit, having little other purpose was to provide a vehicle for Tauber’s singing. Despite his popularity, Die grosse Attraktion (Max Reichmann, 1931) failed badly at the box office,

leading to the collapse of the Richard Tauber Sound-Film Company. As would happen again during his career, he recouped the financial losses with a lucrative concert tour of Britain and America. When he returned to Germany in 1932, it was clear that a different approach would be necessary if he was going to be attempt another film.

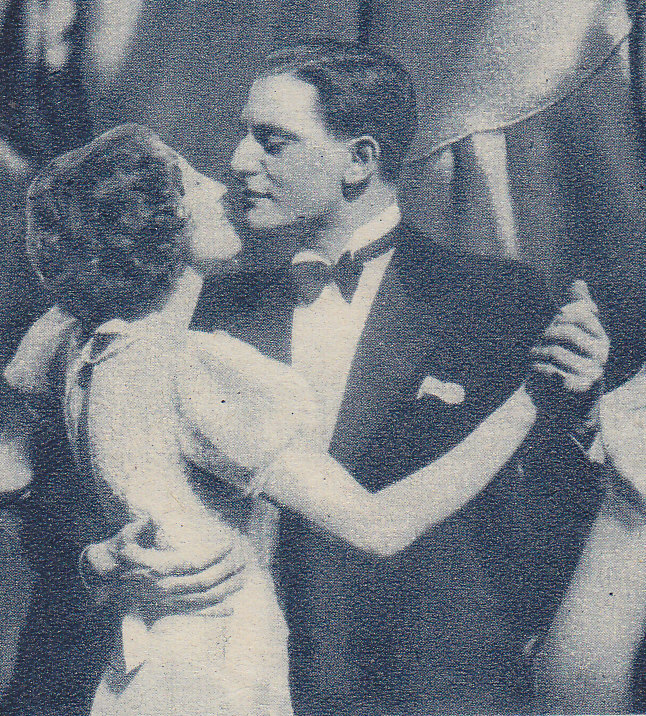

Thankfully the script for Melodie der Liebe (Georg Jacoby, 1932) was much stronger than previous screenplays and provided cinema audiences with a decent story to follow between the musical sequences. Tauber played Richard Hoffman, an eminent singer who has lost his wife and is travelling in the company of his brother in law Bernhard (Szoke Szakall) and young daughter Gloria (Petra Unkel), prior to his departure for a tour in America. After a chance meeting in a pub, he falls for a young woman named Lilli (Alice Treff), unaware of her real intention: she is already engaged to Erwin Richter (AW), an ambitious conductor who sees Hoffmann as a means of furthering his own career. While this pair devise a plan to exploit Hoffman’s infatuation, and Lilli’s hard-up parents do their best to secure a match, the singer’s daughter has met charming young artist Escha (Lien Deyers), who sees right through Lilli’s pretence. Things come to a head as Hoffman prepares for his farewell performance of Tosca: will he find true love before he sails for New York in the morning?

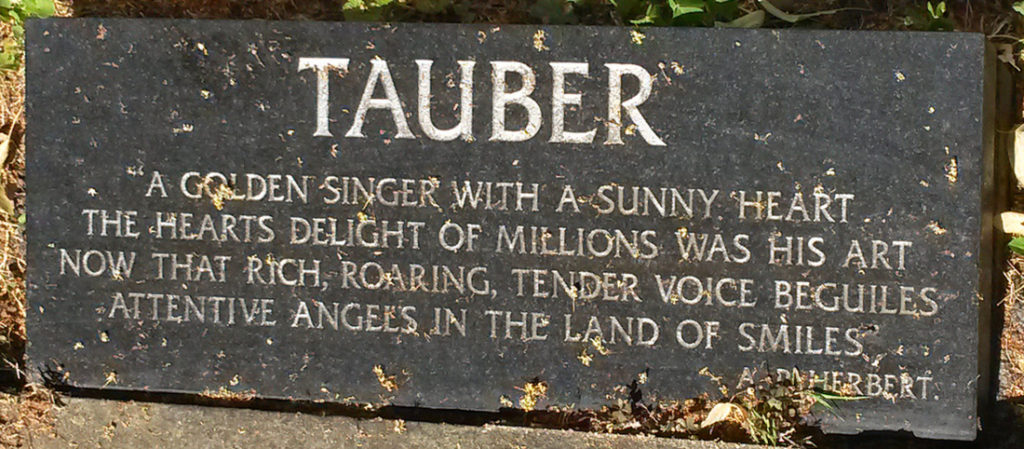

Ten years later the BBC Home Service presented an hour long programme, ‘The Richard Tauber Story’ to mark the anniversary of his death. The radio programme was broadcast at 8 pm on Wednesday 8 January 1958, narrated by Evelyn Laye (AW’s co-star in the 1954 musical Wedding in Paris) with contributions from Walbrook, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Percy Kahn, Jane Baxter and Tauber’s widow Diana Napier.