Author Archive: James

Bear essentials

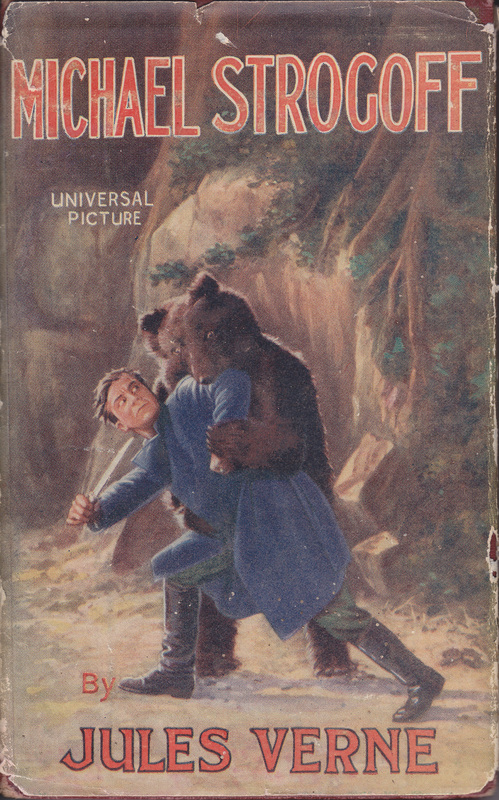

Jules Verne’s novel Michael Strogoff: the Courier of the Csar was first published in 1876 and is regarded as one of his finest works. It is a stirring tale, concerning the adventures of Michael Strogoff, who acts as courier for Tsar Alexander II and has to dash across Siberia to warn the Tsar’s brother – governor of Irkutsk – of planned treachery by a local Tartar warlord named Ivan Ogareff. Strogoff encounters various characters on his journey – Nadia, daughter of a political exile, two journalists reporting the war – as well as his mother in Omsk, where he is captured while visiting. Nadia and Strogoff’s mother are forced to watch as Michael is (apparently) blinded with a hot blade by the cruel Tartars, but he later escapes and reaches Irkutsk where Nadia’s father helps defeat the rebellion, before giving Strogoff his daughter’s hand in marriage.

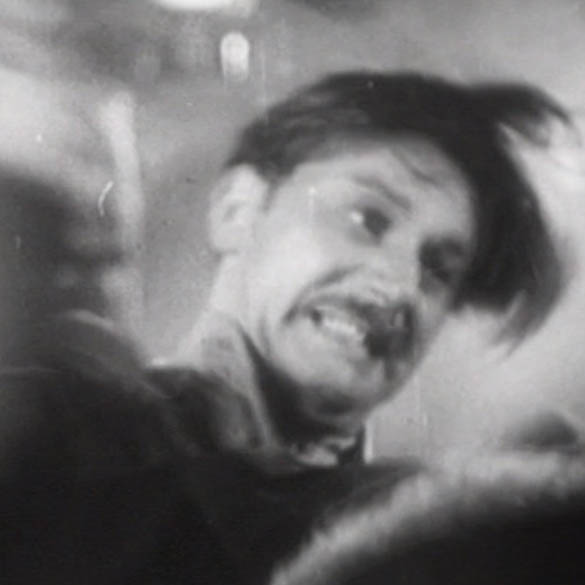

The novel was adapted for the silent screen in 1926, with Ivan Mozzhukhin in the title role – the same actor also played Hermann in an early silent version of The Queen of Spades (Protazanov, 1916), endowing him with the rare distinction of prefiguring AW’s roles in two films. In 1935, although less than ten years had passed since Tourjansky’s movie, it was decided that the time was ripe for a remake (as I said above, nothing is new in the movies!), taking advantage of the advent of sound and improved technology.

I’ve written elsewhere about certain scenes in the film where AW’s posture evokes the iconography of Saint Sebastian but here I want to focus on his fight with the bear. As readers of this blog are probably aware, the actor was actually a great animal lover, and I’ve collected together a number of postcards and images celebrating this here. The scene perhaps jars less with the actor’s personal attitude when it is understood that Strogoff kills the animal while defending a helpless woman who has fainted in fright at the bear’s feet.

In the novel, the incident occurs in Part I, Chapter XI (pp.76-77 in my copy of the film tie-in shown above) and differs considerably from the screen versions. Here, Strogoff and Nadia are travelling through the forest in the company of the two journalists when ‘a monstrous bears’ bursts out the trees and attacks their horses. Nadia tries to defend the horses with her gun, but Strogoff leaps between her and the animal, knife in hand, and swiftly despatches the bear, executing ‘in splendid style the famous blow of the Siberian hunters.’

In the film Der Kurier des Zaren (Eichberg, 1935), the bear attack takes place on board a ship. Strogoff and Nadia (Maria Andergast) are among many passengers watching a group of gypsies on deck, one of whom is goading a ‘tame’ bear to perform tricks for their entertainment. The animal is startled by the magnesium flash on the journalists’ camera, attacks its trainer and breaks free. Strogoff runs forward to save an elegantly-dressed lady (Hilde Hildebrand) who has collapsed in fright, little knowing that she is in fact Zangara, the lover of Ogareff, who will later betray him.

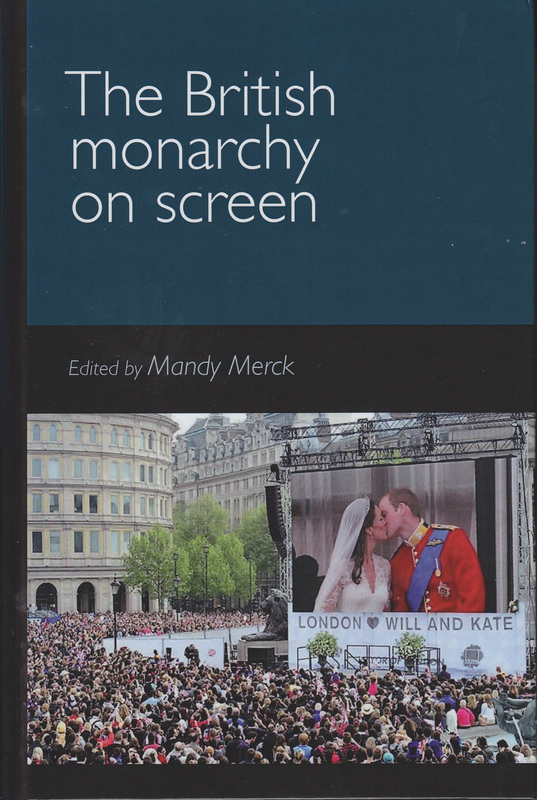

The British Monarchy on Screen (2)

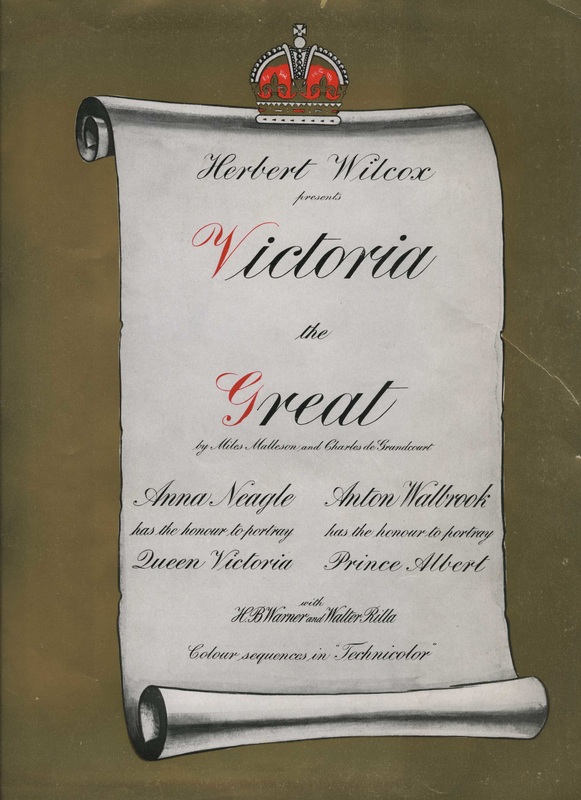

The first thing to strike the eye is, of course, the change of cover picture, and I must confess to feeling a stab of disappointment in seeing that Anton was no longer on the cover, unlike in the the original proposed version (right.) This photograph of AW and Anna Neagle together in Victoria the Great does however appear within my chapter along with another still from that film showing AW seated at the piano surrounded by young ladies of the royal court. Mine was not the only paper to look at Wilcox’s films, and Professor Steven Fielding’s ‘Heart of a Heartless World: Screening Victoria’ discusses the political aspects of the films in comparison with other screen portrayals of the queen.

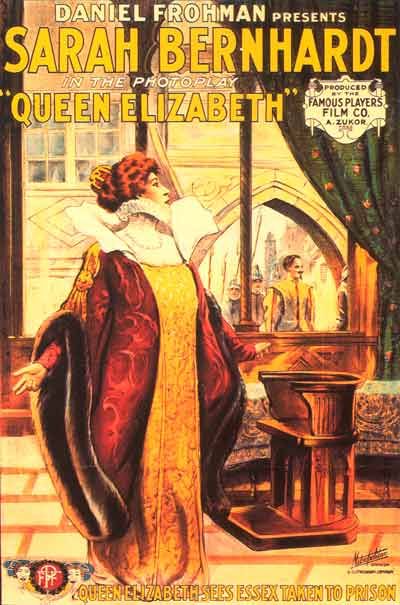

Despite inevitable overlaps like the above, an impressively diverse range of films and television programmes come under scrutiny, beginning with Victoria’s early involvement with photography and her depiction in silent cinema – such as the lost Sixty Years a Queen (Barker & Samuelson, 1913) and Queen Elisabeth (Desfontaines & Mercanton, 1912) starring Sarah Bernhardt (below.)

Moving beyond Sarah Bernhardt’s performance, cinematic portrayals of Elizabeth I proved a popular subject for examination. One paper was devoted to Quentin Crisp’s casting in the role in Orlando (Sally Potter, 1993) while another cast a critical eye over a series of film interpretations – Flora Robson in Fire Over England (Korda,1937), Bette Davis in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (Curtiz, 1939) and The Virgin Queen (Koster, 1955), Jean Simmons in Young Bess (Sidney, 1953), Cate Blanchett in Elizabeth (Kapur, 1998) and its sequel Elizabeth: the Golden Age (Kapur, 2007) as well as Judi Dench in Shakespeare in Love (Madden, 1998) – for which she won an Oscar, despite only being onscreen for about eight minutes.

Her award reflects something of the iconic prestige that is attached to screen portrayals of royalty – an association that received extensive, and sometimes critical, attention during the conference. One key theme was the way in which both the monarchy and film-makers exploit each other to further their own interests- The Queen (Frears, 2006), for example, was described by David Thomson as ‘the most sophisticated public relations boost HRH had had in twenty years’, while directors such as Herbert Wilcox were equally adept at endowing their promotional materials with symbols of regal status:

Dr Phene’s House of Mystery

At first glance I (mis)read the caption as ‘Dr Phibes’, the vengeful protagonist played by Vincent Price in The Abominable Dr Phibes (Fuerst, 1971) but there’s a good case to be had for making an equally memorable film about the man who built the House of Mystery.

Dr John Samuel Phene FRIBA, FRGS (1824-1912) – architect, property developer, traveller, collector, scholar and antiquarian – studied at Kings Lynn Grammar School, Durham University and Trinity College Cambridge before being articled to the firm of an architect by the name of Hardwick.

He seems to have inherited some property in Chelsea sometime before 1850, and in the following years he had constructed a number of buildings in what would become Oakley Street, Margaretta Street and Terrace (both named after his wife Margaretta Forysth, whom he married in 1850), Phene Terrace and Upper Cheyne Row. The Phene Arms was built in 1853 and is still a popular pub to this day. Phene had it built to provide a social hub for local tenants and he seems to have been a progressive thinker, planting trees on both sides of Oakley Street ‘to purify the air and help prevent epidemics.’

From his house at 32 Oakley Street he supervised the construction of ‘The House of Mystery’ on the corner of Upper Cheyne Row. Work seems to have begun in the early 1900s, and its curious appearance led locals to call it the ‘Gingerbread Castle.’ Phene, however, called it ‘The Chateau’ and a close-up of the lettering above the doorway reveals the words: ‘Renaissance du Chateau de Savenay’ – rebirth of the castle of Savenay – in honour of the area in France’s Loire valley that Phene claimed as his ancestral home.

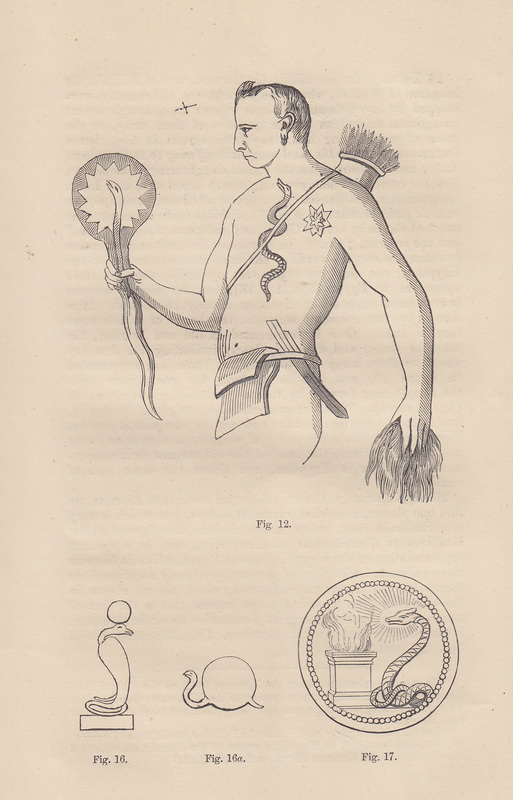

It’s a curious (albeit impressive) piece of work that examines the links between diverse traditions of sun and serpent worship around the world, from the Scottish Hebrides (where Phene spent several years and considerable expense looking for carved stones depicting serpents) to Egypt, America, Mexico, Greece and the west coast of Africa. The insights into ancient history might (or might not be) valuable, but the paper reveals some intriguing details about contemporary events: a footnote on p.4 informs us that ‘A curious illustration of fondness for serpents exists at Chelsea at the present time, which has led to alarm in the neighbourhood.’

A full list of his published work would be too long to detail here, but as a Life Member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science he presented papers at a number of their annual meetings, including ‘On some Evidences of a Common Migration from the East’ (Brighton, 1872) and ‘On the District of Mycene and its early Occupants.’ (Plymouth, 1877.) The British Library lists five publications:

Reptile Tumuli. A lecture … Reprinted from the ‘Paisley and Renfrewshire Gazette.’ [16 pages]

Paisley : J. & J. Cook, 1871

Records of the Past. A lecture. [16 pages]

Paisley : J. & J. Cook, 1873

On the Causes of Art: with an outline of the origin and progress of art from prehistoric to modern times … A discourse … Reprinted from ‘The British Architect.’ [19 pages]

Manchester ; London ; Glasgow, 1874

Victoria Queen of Albion : an idyll of the world’s advance in her life and reign.

London: Blades, East and Blades, 1897. [165 pages]

This was written in verse, with twelve pages of plates, plus an appendix carrying article on Roman London – presumably by Phene – which appeared in several newspapers and magazines in 1896

Exhibits by Dr. Phene in the Ecclesiastical & Educational Exhibition in the Imperial Institute, Kensington, October 7th to 14th 1899. [8 pages]

London, 1899.

His long-standing interest in Scottish antiquities confirmed by a ‘Photograph of wooden idol from deep peat in Scotland’ taken by Phene in 1900 and registered with the Copyright Office. At the same time he also registered his ‘Photograph of the Great Stone Ship Temple in Minorca. (Plate 1 of group of ten)’ and ‘Photograph of remains of pre-Roman and Old Roman London, sculptured masonry now in the Guildhall Museum, to illustrate Mr Roach Smith’s discovery of Sculptured Masonry in the foundations of the old Roman wall of London, testifying to a Pre-Roman stone built city of the Trinobantes (Plate 5 of group of five)’ – further evidence of his fascination with ancient stones.

Although sometimes referred to as a reclusive character, there seems to be plenty of evidence of social activities, including a photograph of him taken by Sir Benjamin Stone outside the House of Commons on 2 July 1907 in the company of Mark Twain and other gentlemen. His membership of numerous activities actually suggests a gregarious nature, and he was also an active member of the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Society of Literature; following his death tribute was paid to him by Sir Edward William Brabrook (1839–1930) that offers further proof of his diverse interests:

‘I must first mention my dear old friend Dr. John Samuel Phene, who had reached his eighty-ninth year. He had been a member of the British Association since the year 1863 was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1872, and Joined our Society in 1875. In the year 1892, when Lord Halsbury became President, Dr. Phene and I were added to the list of Vice-Presidents, of which list, as it then stood, I am now the last survivor. His deep interest in the Society was manifested by his contributing not fewer than eight papers to our Transactions, in which he brought great erudition and shrewd observation to bear upon a variety of subjects, viz.: ‘Linguistic Synonyms in the Pre-Roman Languages of Britain and of Italy’ (vol. xv), ‘King Arthur and St. George’ (vol. xvii), ‘Ethical and Symbolical Literature in Art’ (vol. xviii), ‘ δενδροϕορία or Tree Transporting’ (vol. xix), ‘Place Names in and around Rome, Latium, Etruria, Britain, etc., with Earthworks and Other Works of Art illustrating: such Names’ (vol. xx), ‘The Rise, Progress, and Decay of the Art of Painting in Greece’ (vol. xxi), and ‘The Influence of Chaucer on the Language and Literature of England’ (vol. xxii). There was thus, in recent times, hardly a year in which he did not make some communication to our Society: he was regular in attendance at our Councils up to the last year of his life.’

– Report of the Royal Society of Literature, (1912) pp.12-13.

The stories about his reclusiveness may have some truth, for it seems that the doctor began building Cheyne House for his wife, and after her death he lost interest in the project and began to spend more time alone. He rarely left his Oakley Street residence after this, while the House of Mystery and Cheyne House in Upper Cheyne Row – now a storeroom for his collection of stones – were both boarded up and abandoned. The four acre garden behind the house was strewn with large statues and other curios.

For those interested in reading more about Dr Phene, there’s an article on him in the July 2013 edition of Fortean Times (which I must confess I have not yet read), and also a nicely-illustrated blog post here.

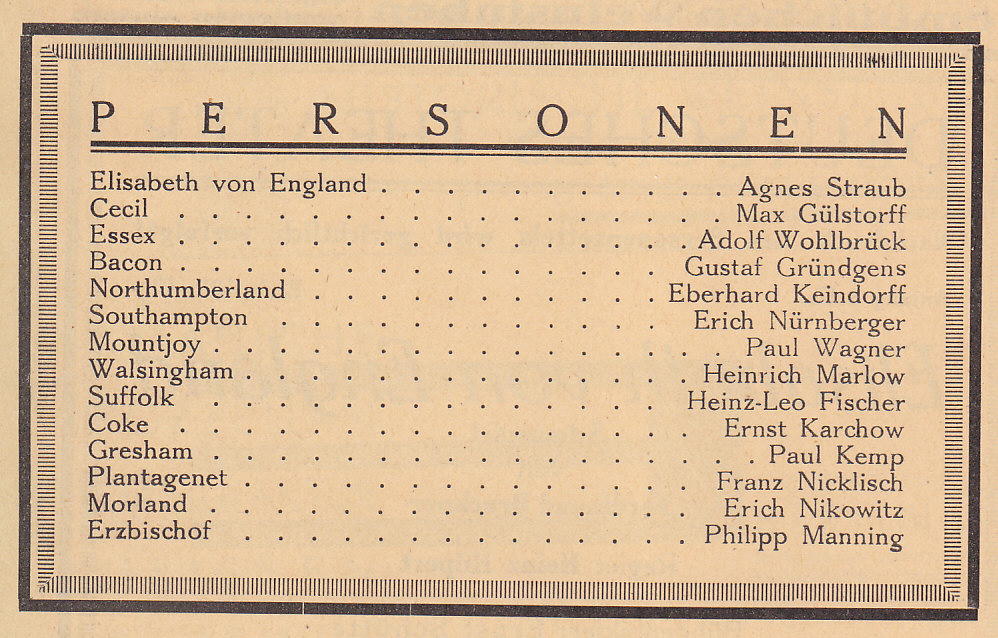

Max Gülstorff and Adolf Wohlbrück

Recently the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum – where I have worked as a volunteer for many years – acquired a large album of photographs and press cuttings compiled by Max Gülstorff that had been passed down through his family. It contains 64 large pages of pictures, in between which are loosely pressed a mass of newspaper cuttings, theatre programmes, photographs and other ephemera. I have written a blog post on the album for the museum’s website which you can read here, but I wanted to give a short overview of Gülstorff’s life and the points of intersection with AW’s career.

Max Walter Gülstorff was born on 23 March 1882 in Tilsit, East Prussia, (now the Russian town of Sovetsk) and began working in provincial theatres in his late teens. He moved to Berlin about 1911 and four years later joined Max Reinhardt’s ensemble at the Deutsches Theater. This was around the same time that young Adolf Wohlbrück enrolled at Reinhardt’s drama school which was attached to the theatre, so as a student AW would have had many opportunities to watch Gülstorff perform on stage. There is a photograph in the album of Gülstorff with three other famous members of the company: Emil Jannings, Paul Hartmann and Werner Krauss, all of whom AW worked with either on stage or screen.

He began appearing in silent film in 1916, and one of his earliest roles was playing Uncle Eli alongside Conrad Veidt in Jettchen Geberts Geschichte (Oswald, 1918.) He went on to appear in over forty silent films during the 1920s, using his skill as a character actor to bring life to minor roles such as schoolmasters, professors, doctors and pompous officials, while continuing to appear regularly on stage (below.)