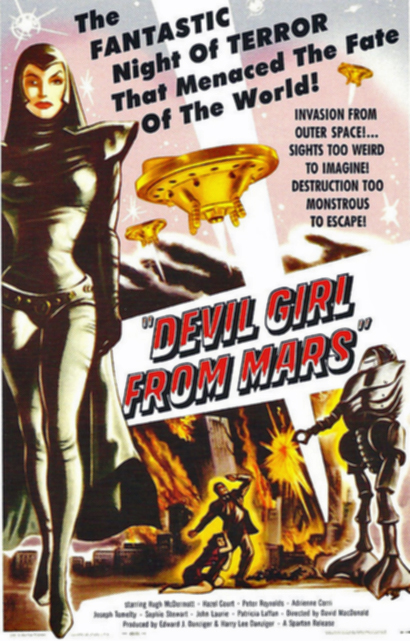

Thirteen years before Mars Needs Women, the red planet was apparently running drastically low on the other sex. To balance the numbers, a female Martian named Nyah – clad in black leather and accompanied by a giant robot – travels to earth on a mission to round-up suitable males for breeding…

This is the premise of Devil Girl from Mars (David Macdonald, 1954), a curious movie that certainly fits the ‘accidentally hilarious’ category, but also one that possesses some unusual quirks which set it apart from other science fiction B-movies of the decade. Distinctly British in its approach and execution, Devil Girl from Mars is played with a seriousness that contrasts starkly with its low-budget effects and stage set.

The basic concept was by no means unique, for the early 1950s saw a wave of Hollywood movies about alien intruders, including The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), The Man from Planet X (1951), The Thing from Another World (1951), Invaders from Mars (1953) and The War of the Worlds (1953.) Without denying that these films may have had some influence, Devil Girl from Mars was a British production and feels very different from the American science-fiction movies it might have imitated. There are elements of the ‘country house mystery’ in the way disparate characters are drawn to the remote inn, a concern for matters like social class, moral behaviour, justice and redemption – plus a very British appreciation for tea and other beverages. Some of these elements betray the film’s radio play origins, although I have been unable as yet to trace any broadcast details. In structure and pacing the film remains stagebound, with its limited locations, excessive speechifying and over-reliance on dramatic entries and exits.

None of this can be anticipated from the film’s opening shots, however, in which an aircraft is mysteriously destroyed in mid-air. The mystery is not just in the mode of destruction, but also in its relevance to the story: it is never explained what this has to do with Nyah’s mission.

Following the plane explosion and the title credits, the scene switches to the Bonnie Charlie Inn ‘in a lonely part of Inverness-shire,’ which will be the setting for the rest of the film. Despite being closed for the winter, there are four staff in residence – Mr and Mrs Jamieson (John Laurie and Sophie Stewart), barmaid Doris (Adrienne Corri) and handyman David (James Edmond) plus Mrs Jamieson’s young nephew Tommy (Anthony Richmond). They have only one guest, glamorous model Ellen Prestwick (Hazel Court), who has come here to hide from her married lover.

This small household is soon bolstered by the arrival of escaped convict Robert Justin (Peter Reynolds), who was actually Doris’s lover before he was jailed for killing his wife, although her death appears to have been accidental: (and as Doris points out in his defence, ‘she was bad’.) Doris took the job at the Bonnie Charlie in order to be nearer Robert, although one wonders why she didn’t choose a pub nearer Stirling, which must be at least a hundred miles away. She might have been safer too, given the apparent pickpocketing powers of fish in the Highlands:

Isn’t it awful, Mrs Jamieson? He’s lost his wallet, he’s just been telling me…There he was crossing the stream, and he..he looks over to see a fish that’s in the water, and the next thing he knows…his wallet’s gone.

Mrs Jamieson will not withhold the Highland tradition of hospitality, but she gives Robert a suspicious look and warns him, ‘I’m counting the spoons.’

Next to arrive are Professor of Astrophysics Arnold Hennessy (Joseph Tomelty) and reporter Michael Carter (Hugh McDermott) from the Daily Messenger, who got lost in their car on their way to investigate reports of a meteor.

Nyah’s explanation of the repair process introduces the first of several technical discussions: we learn that the spaceship is made of organic metal that repairs itself by regeneration. The concept of a ‘living spacecraft’ was, I think, quite original at this time. A short while later Professor Hennessy quizzes Nyah on her spaceship’s power source:

N: A form of nuclear fission, on a static negative condensity

H: A negative condensity?

N: Exactly. Your atomic bomb is positive, it can cause an explosion to expand upwards and evaporate; our force is negative and explodes atomic forces into each other, thereby magnifying the power a thousand fold.

H: And the fuel?

N: Self-propagating

The science may be flaky in the extreme (don’t ask about the ‘perpetual motion chain reactor beam’), but there is something impressive in the deadpan seriousness with which it is presented. Despite its campy and unintentionally comic elements, this is an ambitious little film.

How many earth men could Nyah have fitted in here?

How many earth men could Nyah have fitted in here?

The notion of the self-repairing spaceship is crucial to the plot. Nyah is stranded at the Bonnie Charlie for ‘four earth hours’ until her ship is ready to fly again, forcing her to kill time with the inn’s residents while she waits. Viewers of the film start to feel much the same way, as an inordinate amount of time is spent watching characters wander backwards and forwards between the spaceship and the inn. Did Nyah travel 200 million kilometres for this?

The purpose of her one-woman invasion of earth is really to test the capabilities of the organic spacecraft, in preparation for a much larger ‘man-hunt’ that will follow shortly. Nyah therefore shows little interest in kidnapping any of the five males at the inn. She takes little Tommy, but then is persuaded by Carter to let him swap with the boy. After Carter has wandered back to the inn, Hennessy strolls out for a look around the spaceship and offers to accompany Nyah to London to act as a guide. She agrees, but he is soon back in the Bonnie Charlie as well. When the ship is repaired and she is ready to leave, everyone is hiding down in the cellar except Robert….

The three women may not be at risk of being whisked back to Mars, but they are as determined as the men are about stopping Nyah’s mission. When Carter introduces the Devil Girl to Mrs Jamieson, the landlady is given one of the best lines in the film:

– ‘Mrs Jamieson, may I introduce your latest guest, Miss Nyah. She comes from Mars.’

– ‘Oh, well, that’ll mean another bed.’

The earthlings face the alien threat with the sort of stiff upper lip and cheeriness typical of British wartime movies. Mrs Jamieson exemplifies the spirit of the Blitz with her down to earth remark:

‘While we’re still alive, we might as well have a cup of tea.’

Tea is not the only beverage drunk at the inn, and copious amounts of alcohol are drunk by Mr Jamieson and Carter in particular. I find it quite refreshing when films of this era depict heavy drinking in such a matter of fact way, without either moral judgment or any suggestion that large and frequent tipples are indicative of a problem.

Patricia Laffan was best known at this time for playing Nero’s vixenish wife, Queen Poppaea, in Quo Vadis? (1951), a film in which Adrienne Corri had a minor role. Laffan excelled in long-legged imperious arrogance.

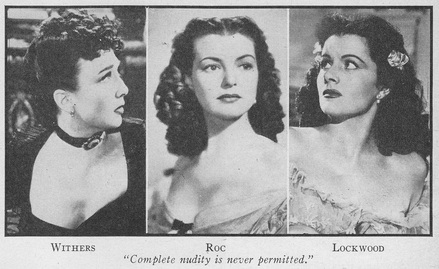

Devil Girl from Mars actually has a pretty good cast compared to similar B-movies of the era:

Shades of Dad’s Army – ‘Shoot, man, shoot!’

Shades of Dad’s Army – ‘Shoot, man, shoot!’

Devil Girl from Mars is probably best remembered for two costumes: Nyah’s black PVC dominatrix uniform and Chani’s cardboard fridge & styrofoam coffee-cup arms. These Martian invaders make an odd couple, and though they were clearly inspired by the pairing of Klaatu and the robot Gort in The Day the Earth Stood Still, they fall far short in terms of effective teamwork and combined resources. Despite her impressive robot, powers of hypnosis and ability to enter the fourth dimension, Nyah’s mission turns out a spectacular failure. At the end of the film, is there a moral as to why?

The inability of the Martian women to procreate is symbolised by Nyah’s pairing with the mechanical Chani; furthermore both of them show a total absence of feeling throughout the film. In contrast, the Bonnie Charlie is a hotbed of romance and warm emotions, even in the depths of winter: Doris and Robert are reunited and both show willingness to sacrifice everything to protect the other; Ellen falls for Carter, finding the strength to break away from her married lover while succeeding in breaking through Carter’s cynicism and gruff exterior. Behind the Jamiesons’ constant bickering banter, there seems to be a steadfast relationship and a tender devotion to their young nephew. The cheesy dialogue and over–wrought domestic dramas may well amuse modern viewers, but they show that Devil Girl from Mars was looking in the opposite direction from most of its contemporaries. This is not another Cold War metaphor or guilt-ridden nightmare about atomic power. Devil Girl borrows the trappings of 1950s science fiction while exploring some fairly old-fashioned British themes about love, duty, altruism and moral principles. The similarity between Nyah’s black-booted outfit and the Nazi uniform is surely no coincidence; this is a flying saucer movie that looks to the past as much as the future.

This blog post is part of the ‘Accidentally Hilarious’ blogathon, and there’s some brilliant pieces on other classic films – including silent movies, the work of Ed Wood, more monster/alien flicks and all sorts of wonderful weirdness – to be found here. Enjoy!