Category Archives: All

Dr Phene’s House of Mystery

At first glance I (mis)read the caption as ‘Dr Phibes’, the vengeful protagonist played by Vincent Price in The Abominable Dr Phibes (Fuerst, 1971) but there’s a good case to be had for making an equally memorable film about the man who built the House of Mystery.

Dr John Samuel Phene FRIBA, FRGS (1824-1912) – architect, property developer, traveller, collector, scholar and antiquarian – studied at Kings Lynn Grammar School, Durham University and Trinity College Cambridge before being articled to the firm of an architect by the name of Hardwick.

He seems to have inherited some property in Chelsea sometime before 1850, and in the following years he had constructed a number of buildings in what would become Oakley Street, Margaretta Street and Terrace (both named after his wife Margaretta Forysth, whom he married in 1850), Phene Terrace and Upper Cheyne Row. The Phene Arms was built in 1853 and is still a popular pub to this day. Phene had it built to provide a social hub for local tenants and he seems to have been a progressive thinker, planting trees on both sides of Oakley Street ‘to purify the air and help prevent epidemics.’

From his house at 32 Oakley Street he supervised the construction of ‘The House of Mystery’ on the corner of Upper Cheyne Row. Work seems to have begun in the early 1900s, and its curious appearance led locals to call it the ‘Gingerbread Castle.’ Phene, however, called it ‘The Chateau’ and a close-up of the lettering above the doorway reveals the words: ‘Renaissance du Chateau de Savenay’ – rebirth of the castle of Savenay – in honour of the area in France’s Loire valley that Phene claimed as his ancestral home.

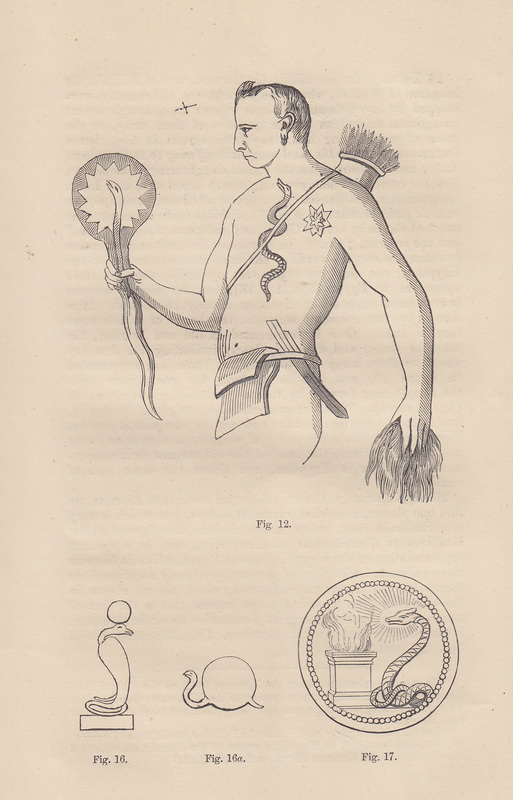

It’s a curious (albeit impressive) piece of work that examines the links between diverse traditions of sun and serpent worship around the world, from the Scottish Hebrides (where Phene spent several years and considerable expense looking for carved stones depicting serpents) to Egypt, America, Mexico, Greece and the west coast of Africa. The insights into ancient history might (or might not be) valuable, but the paper reveals some intriguing details about contemporary events: a footnote on p.4 informs us that ‘A curious illustration of fondness for serpents exists at Chelsea at the present time, which has led to alarm in the neighbourhood.’

A full list of his published work would be too long to detail here, but as a Life Member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science he presented papers at a number of their annual meetings, including ‘On some Evidences of a Common Migration from the East’ (Brighton, 1872) and ‘On the District of Mycene and its early Occupants.’ (Plymouth, 1877.) The British Library lists five publications:

Reptile Tumuli. A lecture … Reprinted from the ‘Paisley and Renfrewshire Gazette.’ [16 pages]

Paisley : J. & J. Cook, 1871

Records of the Past. A lecture. [16 pages]

Paisley : J. & J. Cook, 1873

On the Causes of Art: with an outline of the origin and progress of art from prehistoric to modern times … A discourse … Reprinted from ‘The British Architect.’ [19 pages]

Manchester ; London ; Glasgow, 1874

Victoria Queen of Albion : an idyll of the world’s advance in her life and reign.

London: Blades, East and Blades, 1897. [165 pages]

This was written in verse, with twelve pages of plates, plus an appendix carrying article on Roman London – presumably by Phene – which appeared in several newspapers and magazines in 1896

Exhibits by Dr. Phene in the Ecclesiastical & Educational Exhibition in the Imperial Institute, Kensington, October 7th to 14th 1899. [8 pages]

London, 1899.

His long-standing interest in Scottish antiquities confirmed by a ‘Photograph of wooden idol from deep peat in Scotland’ taken by Phene in 1900 and registered with the Copyright Office. At the same time he also registered his ‘Photograph of the Great Stone Ship Temple in Minorca. (Plate 1 of group of ten)’ and ‘Photograph of remains of pre-Roman and Old Roman London, sculptured masonry now in the Guildhall Museum, to illustrate Mr Roach Smith’s discovery of Sculptured Masonry in the foundations of the old Roman wall of London, testifying to a Pre-Roman stone built city of the Trinobantes (Plate 5 of group of five)’ – further evidence of his fascination with ancient stones.

Although sometimes referred to as a reclusive character, there seems to be plenty of evidence of social activities, including a photograph of him taken by Sir Benjamin Stone outside the House of Commons on 2 July 1907 in the company of Mark Twain and other gentlemen. His membership of numerous activities actually suggests a gregarious nature, and he was also an active member of the Royal Geographical Society and the Royal Society of Literature; following his death tribute was paid to him by Sir Edward William Brabrook (1839–1930) that offers further proof of his diverse interests:

‘I must first mention my dear old friend Dr. John Samuel Phene, who had reached his eighty-ninth year. He had been a member of the British Association since the year 1863 was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1872, and Joined our Society in 1875. In the year 1892, when Lord Halsbury became President, Dr. Phene and I were added to the list of Vice-Presidents, of which list, as it then stood, I am now the last survivor. His deep interest in the Society was manifested by his contributing not fewer than eight papers to our Transactions, in which he brought great erudition and shrewd observation to bear upon a variety of subjects, viz.: ‘Linguistic Synonyms in the Pre-Roman Languages of Britain and of Italy’ (vol. xv), ‘King Arthur and St. George’ (vol. xvii), ‘Ethical and Symbolical Literature in Art’ (vol. xviii), ‘ δενδροϕορία or Tree Transporting’ (vol. xix), ‘Place Names in and around Rome, Latium, Etruria, Britain, etc., with Earthworks and Other Works of Art illustrating: such Names’ (vol. xx), ‘The Rise, Progress, and Decay of the Art of Painting in Greece’ (vol. xxi), and ‘The Influence of Chaucer on the Language and Literature of England’ (vol. xxii). There was thus, in recent times, hardly a year in which he did not make some communication to our Society: he was regular in attendance at our Councils up to the last year of his life.’

– Report of the Royal Society of Literature, (1912) pp.12-13.

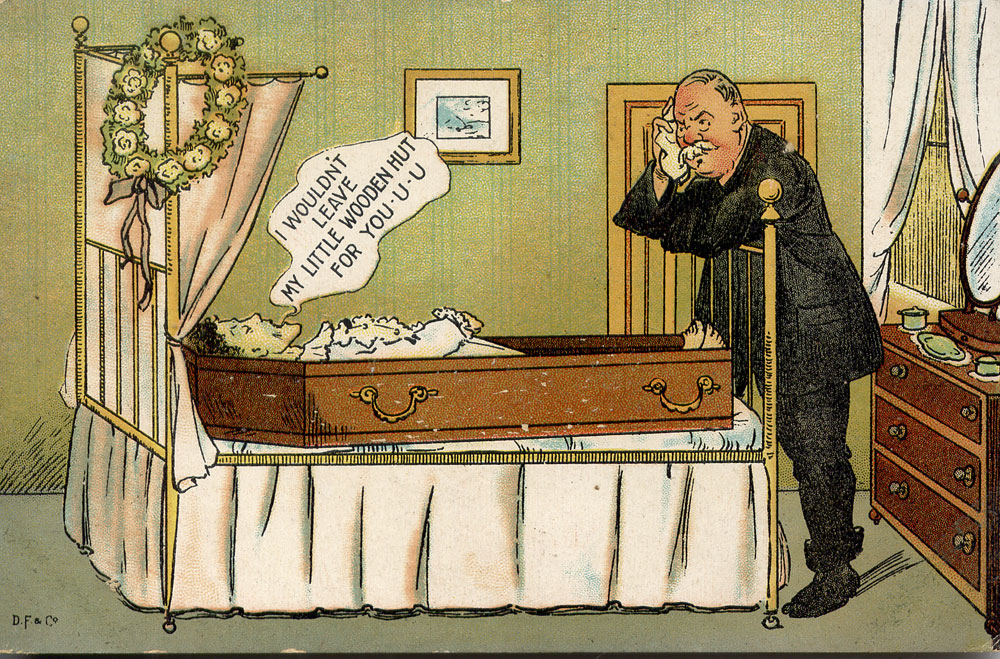

The stories about his reclusiveness may have some truth, for it seems that the doctor began building Cheyne House for his wife, and after her death he lost interest in the project and began to spend more time alone. He rarely left his Oakley Street residence after this, while the House of Mystery and Cheyne House in Upper Cheyne Row – now a storeroom for his collection of stones – were both boarded up and abandoned. The four acre garden behind the house was strewn with large statues and other curios.

For those interested in reading more about Dr Phene, there’s an article on him in the July 2013 edition of Fortean Times (which I must confess I have not yet read), and also a nicely-illustrated blog post here.

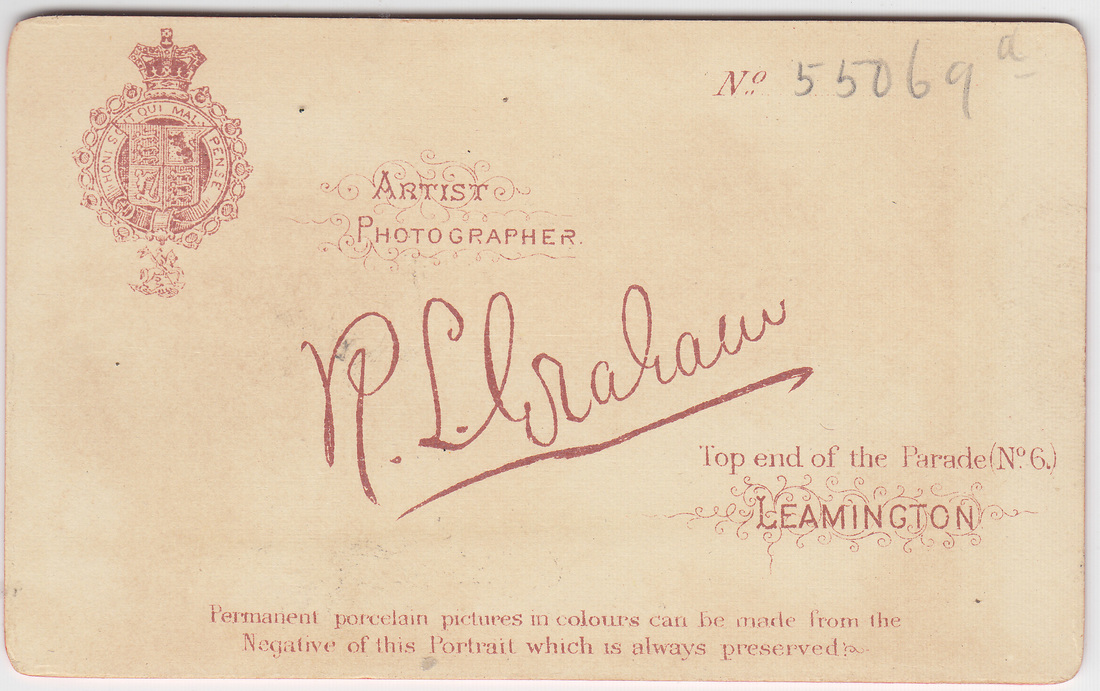

carte de visite of the week #11 robert graham and the love letter

This week’s cdv is a rather charming portrait of a young lady reading a letter. Her natural pose and slight smile make a pleasant change to the forced artifices found in many portraits, where the sitters appear uncomfortable, are grimacing rigidly, or else are engaged in some pretence such as rowing a boat inside the studio. All portraiture, of course, involves an element of performance, and this was even more the case during the early years of photography. However, a cdv portrait like this could almost be imagined as a candid shot in the corner of someone’s living room. Was this letter a studio prop, or did the girl bring it along with her? Does it have personal significance – a letter from a distant relative, friend or lover? Perhaps the carte-de-visite was made for the person who wrote the letter, and would be posted back to them as an affectionate sign that his/her correspondence was both received and valued.

The reverse of the card identifies the photographer as Robert L. Graham, operating from his studio at the Top end of the Parade (No.6), Leamington, Warwickshire. It probably dates to the 1890s: Graham opened his studio at 7a Upper Parade in 1873, later moving to York Terrace and then to No. 6 Parade, expanding into the next door premises (No.8) as his business flourished.

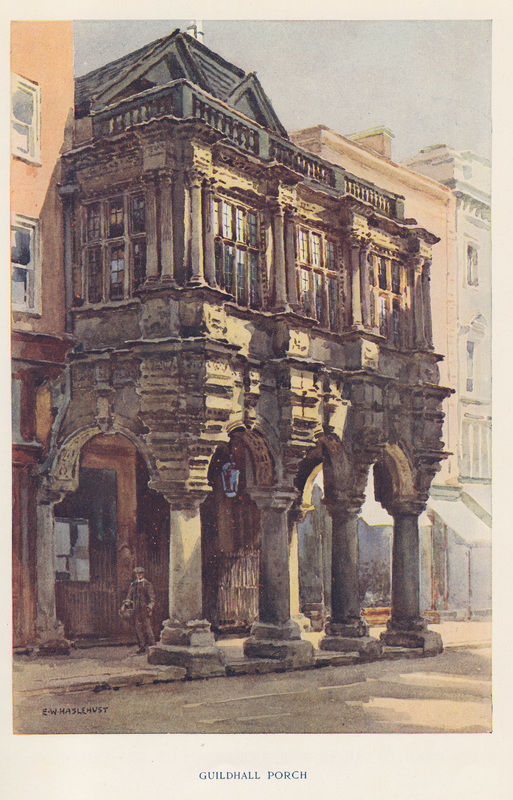

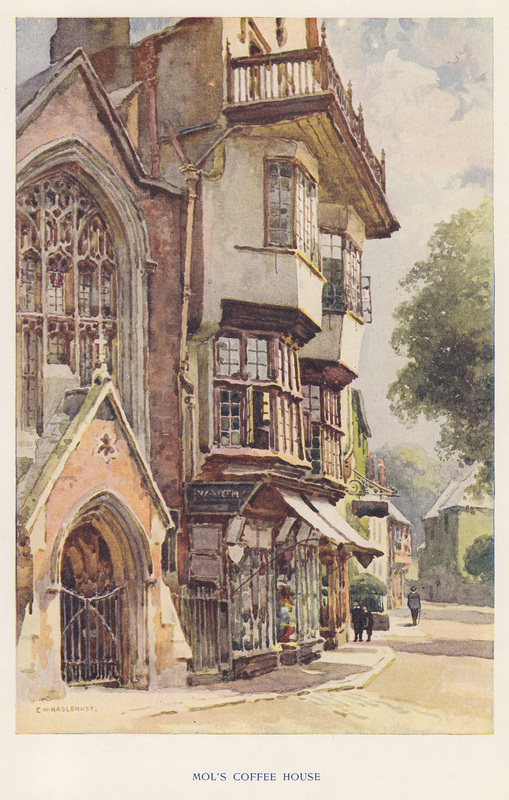

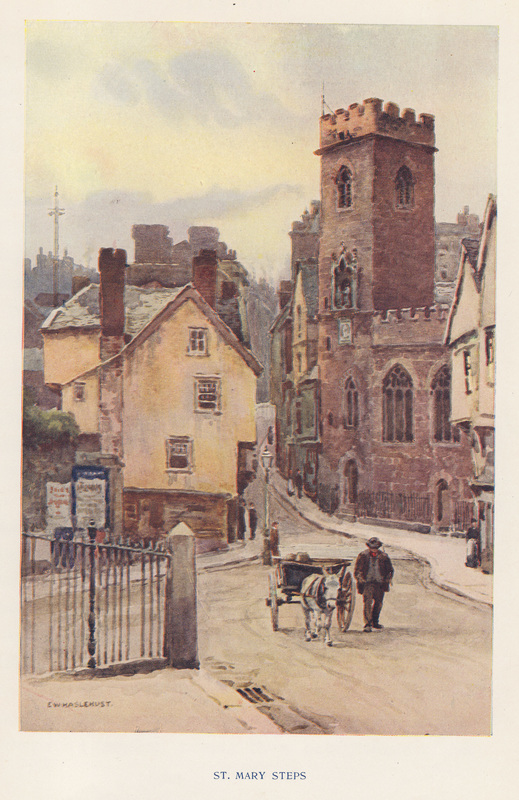

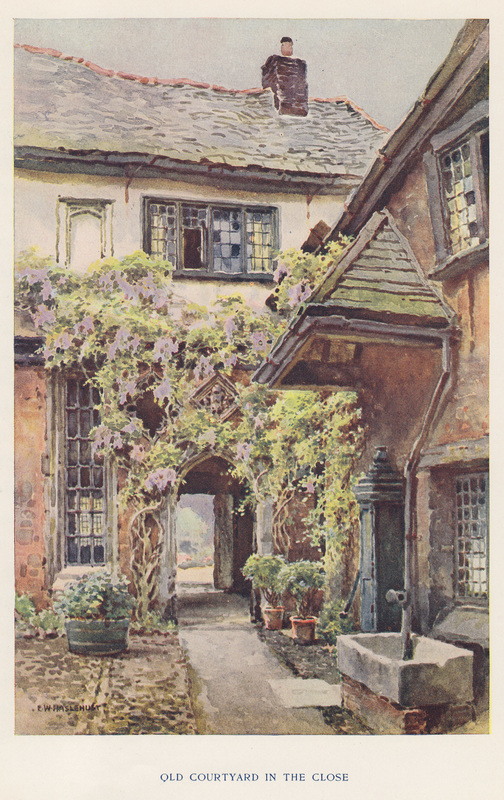

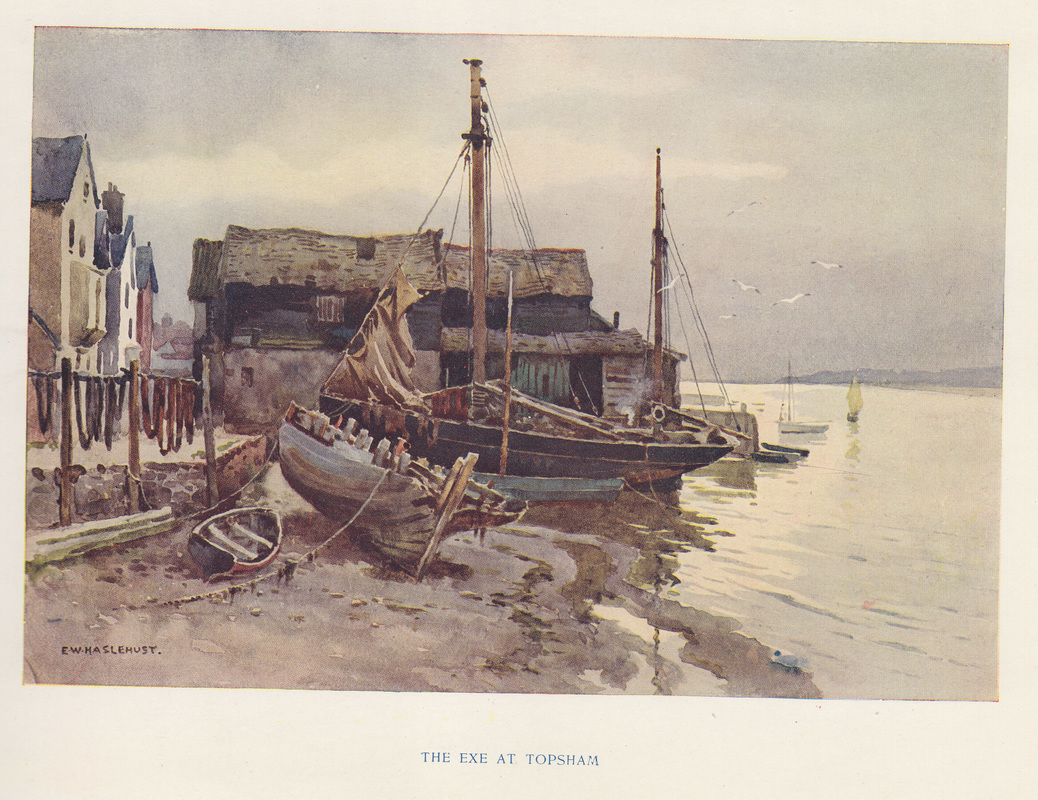

Exeter in 1912 – Watercolours by E W Haslehurst

I walked along this very stretch of water just two days ago and can confirm that little has changed: Topsham remains one of the most attractive spots on the Exe, with tangible evidence of its sea-faring importance all around. After the river became inaccessible to shipping higher upstream, Topsham became a prosperous port and the hub of the area’s maritime trade.

The closure of the River Exe to shipping was due to the construction of a weir in the 12th century. According to the story, this was at the behest of Isabella, Countess of Devon, which provides the derivation for the name ‘Countess Wear’ which is given to the area painted by Haslehurst below – although, like many such stories, the evidence and dates aren’t quite consistent. Behind the housing in Countess Wear the Exe meanders slowly, in long wide arcs, through flat grassy meadows that still provide grazing for cattle today, as well as being a popular route for cyclists and walkers.

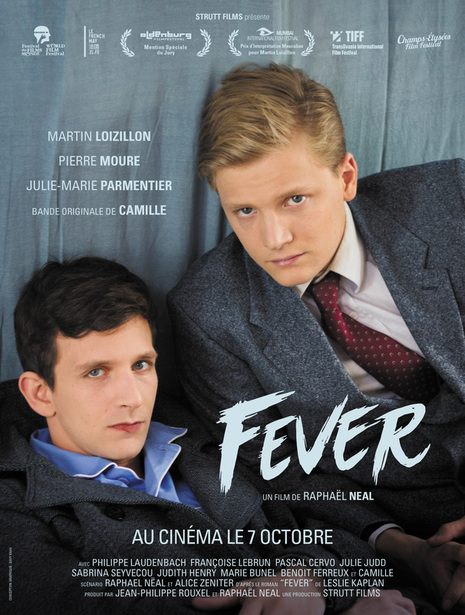

‘Fever’ (Raphaël Neal, 2014)

Texts form an important part of the film. As part of their philosophy class Damien and Pierre are studying Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: a report on the banality of evil (1963); the Nazi’s defence that he was only ‘obeying orders’ is seen by them as a reflection of their own principle that in order for murder to be a crime, there must be a personal motive. Similar themes had of course already been considered in Dostoevsky’s 1866 novel Crime and Punishment.

The events depicted here are no philosophical fantasy however, but are rooted in historical fact. Adapted from Leslie Kaplan’s 2005 novel Fever, the story is inspired by the 1924 murder in Chicago of 14 year old Bobby Franks, which was carried out by two wealthy students, Nathaniel Leopold and Richard Loeb, in order to demonstrate their intellectual superiority. This crime provided the inspiration for the Rope (1929), by Patrick Hamilton (who also wrote Gaslight) – the play was adapted for the screen in 1948 by Alfred Hitchcock. Further layers of historical parallels are woven into the story as the boys grow increasingly anxious and paranoid in the wake of the crime, turning to their grandparents for reassurance while trying to exculpate themselves by reading up on France’s Vichy past. Narratives of personal and national guilt become intertwined with the students’ erratic behaviour. No-one is portrayed in isolation, and by exploring matters such as family dynamics and ancestral roots, the characters are fleshed out in a depth rarely found in contemporary crime thrillers.

The nature of Zoé’s desire is not the only erotic element in the film. The relationships between the main characters are complex and ever-shifting, signified not only by the actors’ sensitive performances but also by a rich backdrop of visual and musical motifs. As I mentioned in a recent post on the noir film While the City Sleeps, unhealthy relationships with one’s mother often feature in movie portrayals of murderers, and there are strong hints here that Damien and his mother are rather more intimate than is appropriate. While there is also a definite homoerotic element in the relationship between Damien and Pierre, we see several shifts in their attitude to the women around them – such as their philosophy tutor Rosine, fellow students and Zoé herself. The alternation between desire, fear, misogynistic contempt and nervous embarrassment represents realistically the confused world of the adolescent. Many of these scenes take place with Peggy Lee’s 1958 hit ‘Fever’ playing in the background, various renditions of the song being performed by fictitious chanteuse ‘Alice Snow’ (actually the singer Camille) – including a striking concert sequence attended by Zoé and an equally memorable dance routine involving Damien and his mother.

Given Raphaël Neal’s background as a professional art photographer, the careful attention given to matters of lighting, pictorial composition and visual iconography is no surprise. As well as allusions to other films – the close-ups of feet descending a spiral staircase recalls Moira Shearer’s frenetic descent in The Red Shoes – there are nods to the work of Irina Ionesco, Peter Weir and Catherine Breillat, amongst others. This is a film that will reveal further riches with repeated viewing. The effective use of outside locations around Montparnasse, including the vast cemetery, provide a lively sense of edgy authenticity. Since making his screen debut as an actor in 2001 Neal has worked with the likes of Claire Denis, Claude Chabrol, Alexander Sokurov and Sofia Coppola, and opportunities to observe these great directors at work have clearly not been wasted. His debut as a director suggests he may have an equally distinguished career ahead.