Category Archives: All

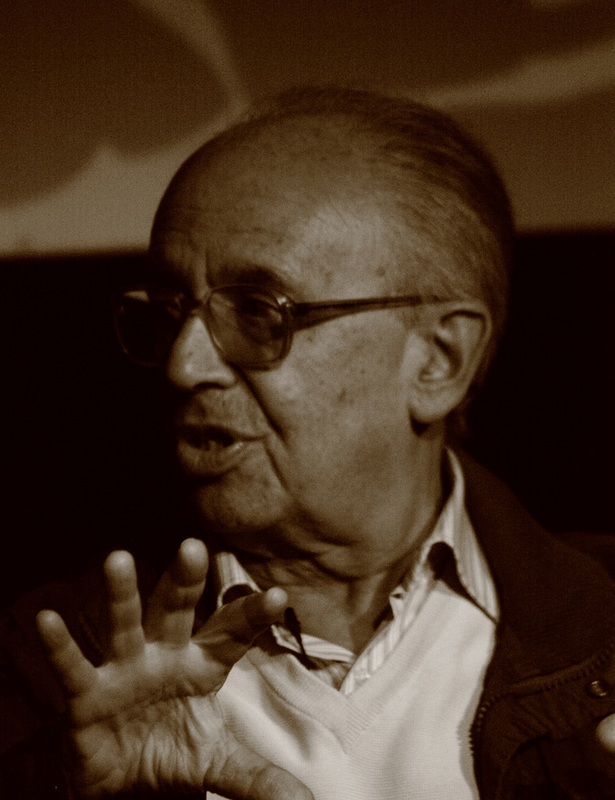

Peter Sasdy at 80

Peter George Sasdy was born in Budapest on the the 27th May 1935. Although he survived the war and the devastation of Budapest, he was forced to leave Hungary after the failure of the 1956 uprising. Arriving in England, he studied drama and journalism at Bristol University before joining ATV in 1958. His first task there was directing numerous episodes of Emergency Ward 10 (1959-60.) He was promoted to director of drama at ATV, before going freelance in 1964. His work included a range of series and standalone plays, ranging from police dramas such as Ghost Squad (1963-64), Isaac Asimov’s Caves of Steel (1964, his first collaboration with Peter Cushing) to two Brontë adaptations, Wuthering Heights (1967) and the four-episode series The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1968-69) starring Janet Munro as Helen Graham.

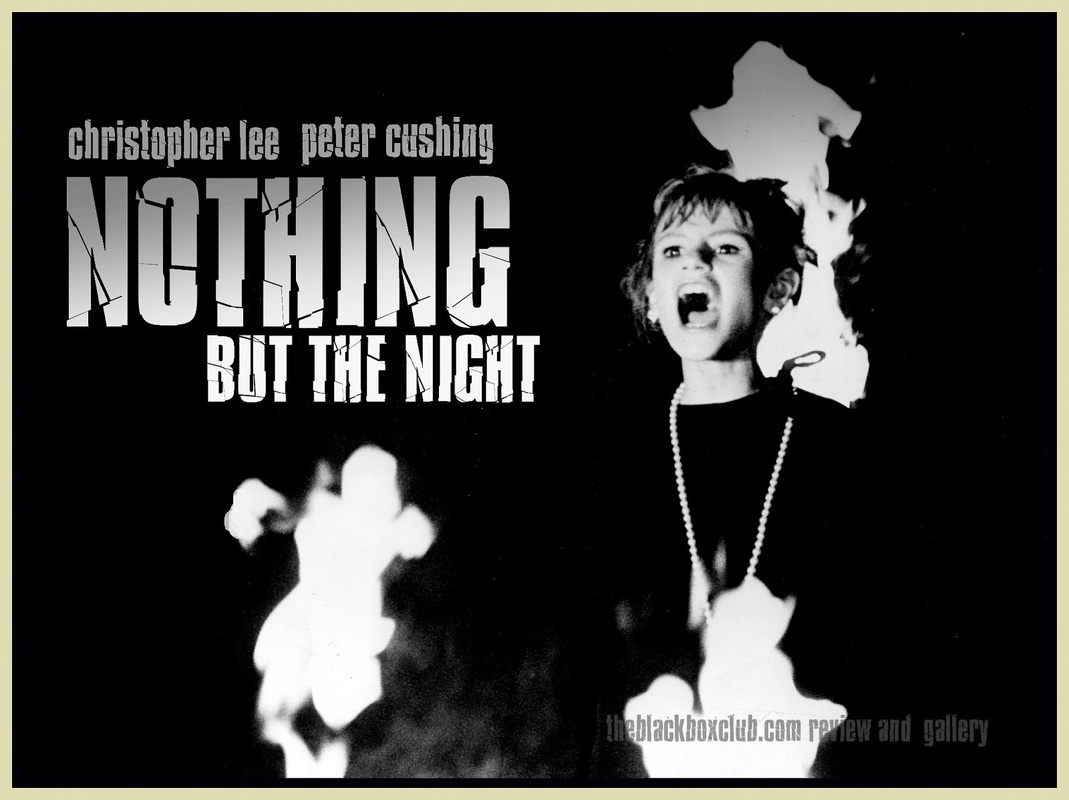

He also directed no less than three productions of Sherlock Holmes, beginning with an ITV episode in 1965 that starred Peter Cushing as the detective. This was later followed by the Polish-British co-production Sherlock Holmes (1979) starring Geoffrey Whitehead, and finally Sherlock Holmes and the Leading Lady (TV movie 1991) starring Christopher Lee.

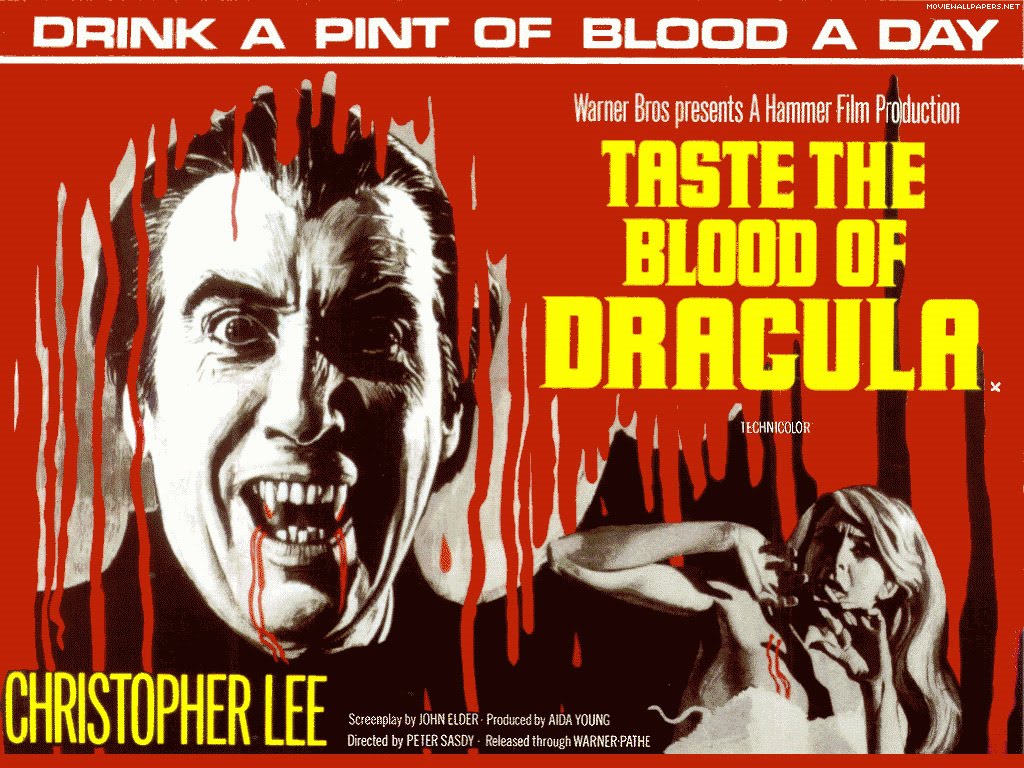

He came to know the two great masters of British horror very well after being taken on by Hammer studios, with whom he made his feature film debut in 1969. Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), was the fifth Hammer film about the Transylvanian count and the fourth to feature Christopher Lee, although Dracula himself has very little screen time. In compensation for some awful dialogue the production values are relatively high, with lavish 19th century sets, shadowy Gothic lighting and some brilliant camera work.

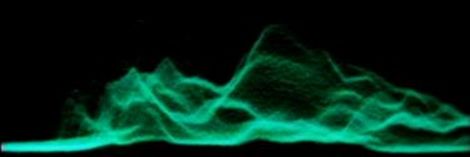

The Stone Tape is probably Sasdy’s finest work and . Shown on BBC2 on Christmas Day 1972 as part of the BBC’s tradition of broadcasting ghost stories at Christmas, Nigel Kneale’s script was unusual in fusing traditional elements – a Victorian mansion haunted by ghostly screams and apparitions – with modern technology. The story focuses on a crew of electrical researchers who have moved into the old house of Taskerlands to concentrate on their new project: to devise an alternative recording medium to magnetic tape, so as to outgain their industrial rivals in Japan. Although the researchers – especially Jill (Jane Asher) – both see and hear apparitions in the house, their sophisticated equipment is unable to record any trace of these – inspiring the team leader Peter Brock (Michael Bryant) to propose a theory: that the supernatural occurrences are actually phenomena that have been recorded by the room itself, and are being replayed through the senses of those present. Does this ‘stone tape’ provide a solution to their technical quest?

The originality of these themes, and the subtle, intelligent way in which they are handled are startling, and it remains a deeply unsettling film even today despite its dated acting style (it comes across as a filmed play, complete with some overtly theatrical performances) and limited effects. The chills come from the sound design rather than the visual effects, as Brock’s team cranks up the noise in order to increase their chances of recording a response from the room’s ‘presence.’

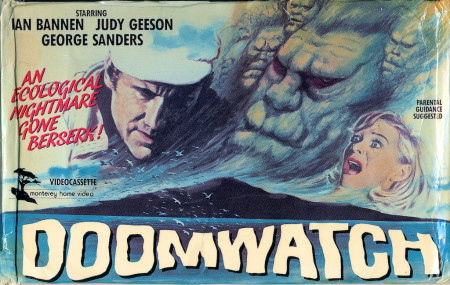

starring Robert Powell, John Paul and Simon Oates that had been inspired by Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass. Again, it was well ahead of its time, tackling the issue of environmental pollution and government cover-ups, albeit with a creepy atmosphere and marketing campaign that would have been more appropriate for a Hammer horrors than for the actual film itself.Both Paul and Oates reprised their roles, with Powell’s place taken by Scottish actor Ian Bannen, and George Sanders playing an admiral. It was filmed in Cornwall, around the area of Polkerris and Polperro.

Some of other Sasdy’s films don’t merit much attention, however, and amongst his worst is Sharon’s Baby (1975), which aimed at replicating the success of Rosemary’s Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968) but fails. Miserably. Attempts to repackage it as I Don’t Want to Be Born, It’s Growing Inside Her and The Monster did not succeed any better. Sasdy even managed to pick up a Razzle Award for Worst Director after The Lonely Lady (1983), an adaptation of Harold Robbins’ best-selling novel that starred multiple Razzle Award winning ‘actress’ Pia Zadora. Of much greater interest was Welcome to Blood City (1977), a science-fiction film that explores the idea of virtual reality over twenty years before The Matrix.

Alongside his film output Sasdy continued doing working for television, including episodes of popular series such as The Return of the Saint (1978-79), Minder (1979) and The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13¾ (1985-87.) His association with Hammer ensured he was kept on board when the studio broke onto the small screen with The Hammer House of Horror (three episodes, 1980) and The Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense (three episodes, 1984.) His last TV production was an Omnibus documentary on another Hungarian director, Alexander Korda, whom Sasdy has often cited as a major inspiration. The disproportionate contribution made by Sasdy’s countrymen to the visual arts has led some to wonder what it is about Hungary that has produced so many brilliant photographers and film directors. But as Korda himself once quipped, ‘It’s not enough to be Hungarian – you must have talent too.’

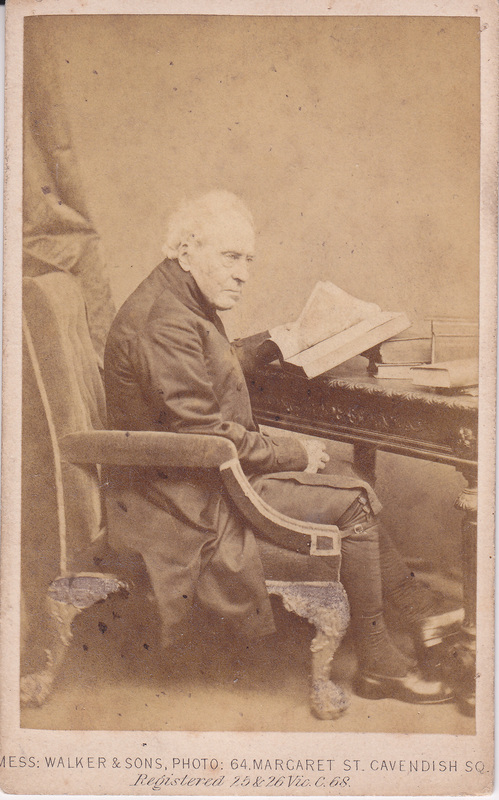

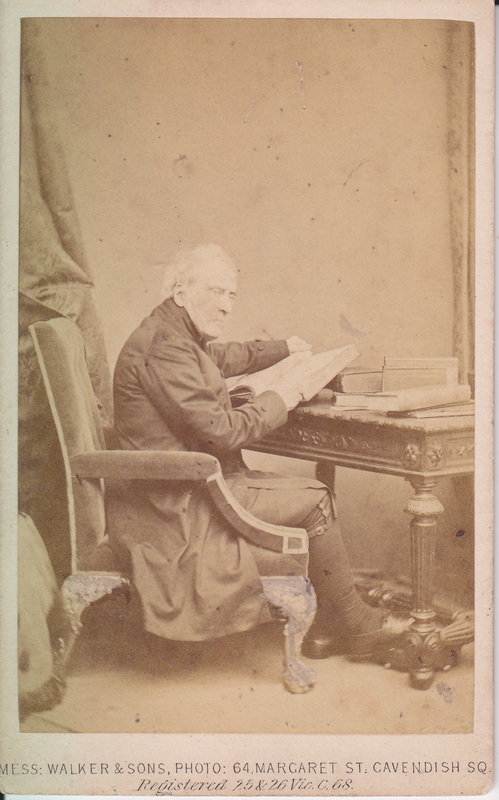

Carte-de-visite of the week #10 Henry PhilLpotts, Bishop of Exeter

Celebrity cards like these were inexpensive to buy – typically between 1/ and 1/6d – and would be sold in stationers shops or other outlets. There was an insatiable market for collecting carte-de-visites of famous people in the 1860s, though one wonders how popular Bishop Phillpotts’ portrait was among collectors, given his unpopularity and fearsome reputation. I remain curious to know more about the person who originally bought this pair of cards. Were they an admirer of the bishop? Did they acquire the cards to go in an album with cdvs of other church dignitaries, or were they collecting cards of local interest to the Exeter area?

Original albums of Victorian cartes-des-visites regularly come up for sale, but often we know little about the way these collections were put together. How often were people buying cards? How much was acquired as part of a clear collecting strategy and how much was picked up on arbitrary impulse, according to what was available or looked appealing? What personal use did the collector make of the images he had acquired? Was the album taken out in the evenings to be pored over as we might do with a glossy ‘coffee-table’ book?

Questions such as these invite comparisons with modern habits of collecting, as well as highlighting the extent to which the meaning and nature of celebrity status has changed over the last 150 years. Some people might be bemused today at the notion of a man like Bishop Phillpotts being regarded as a celebrity, but his contemporaries would be equally baffled, if not more so, at the activities and achievements of those accorded the status of celebrity by the modern media.

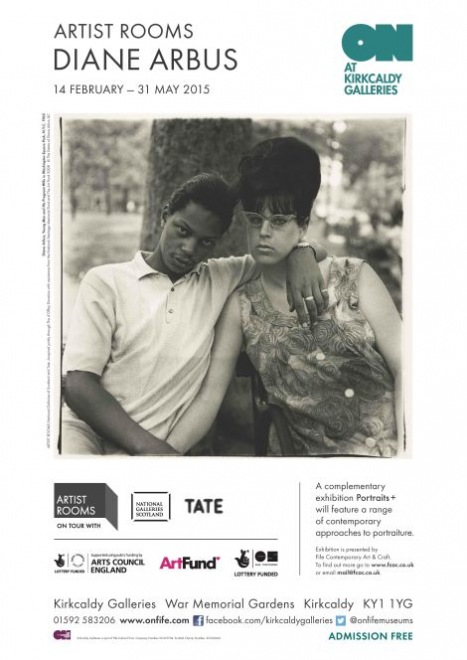

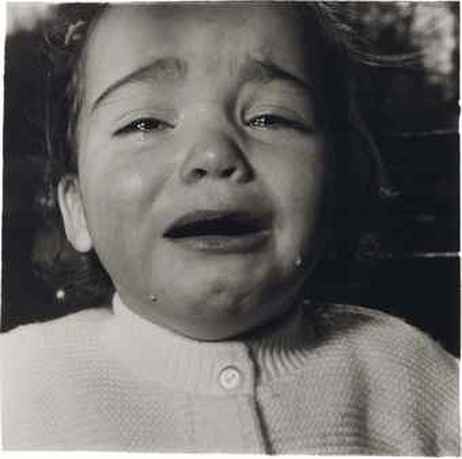

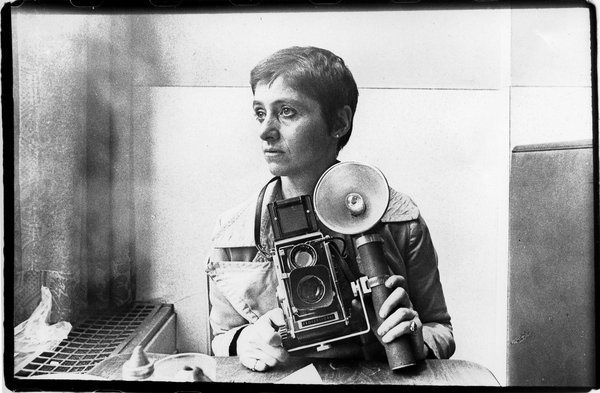

Diane Arbus in Kirkcaldy

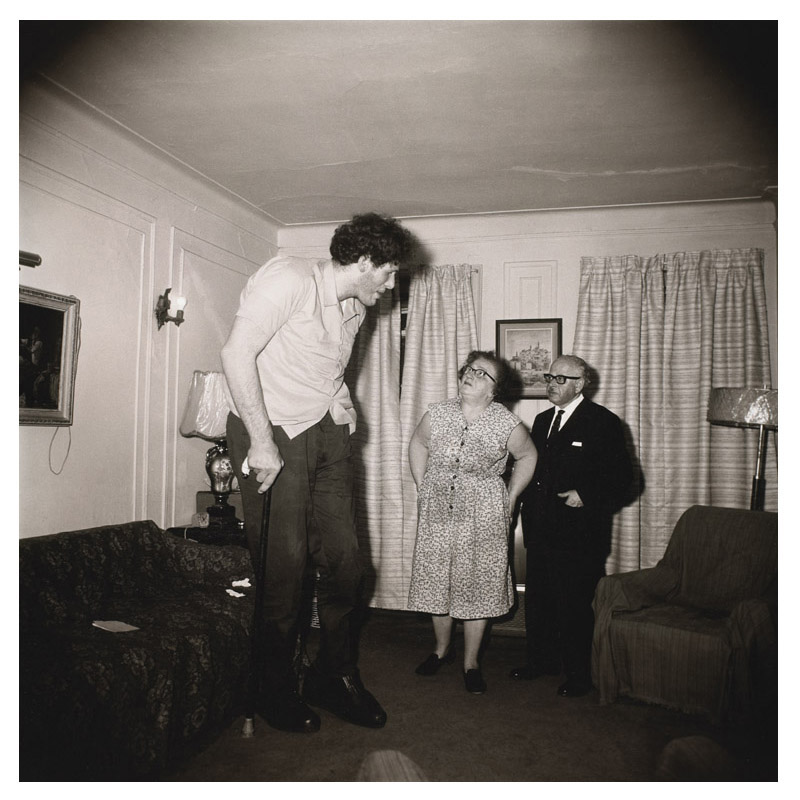

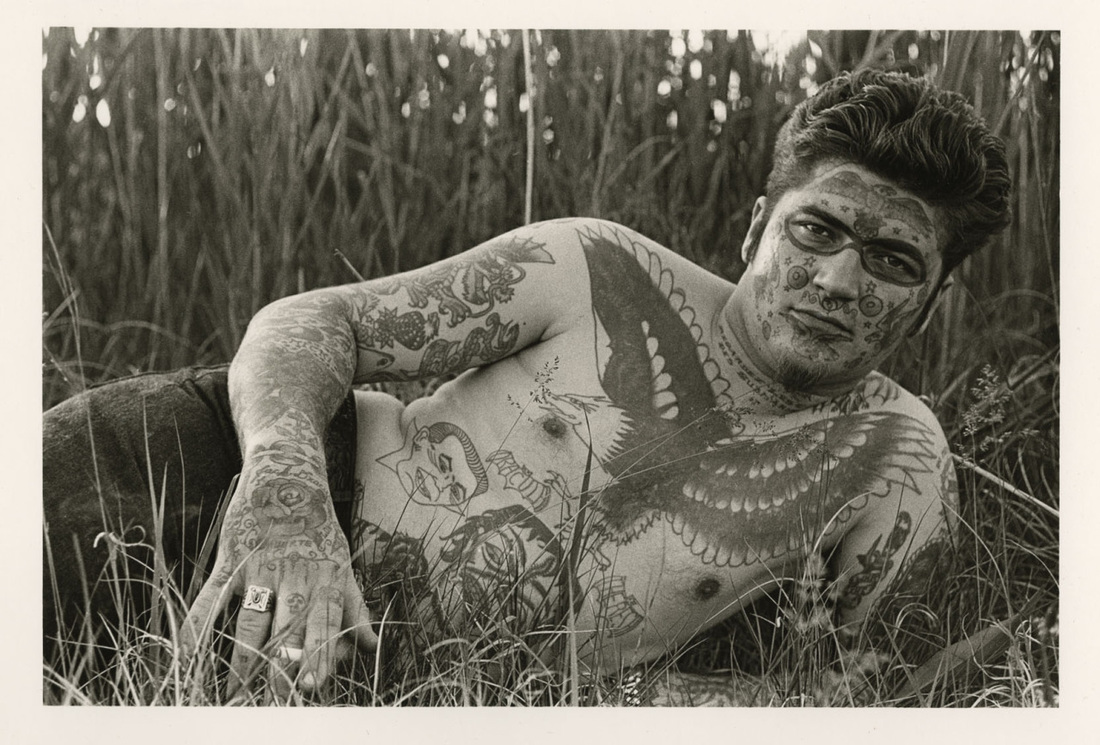

The image above, like the majority of Arbus portraits, is taken face-on, so that the viewer has a direct confrontation with the subject of the photograph. It is this aspect of her work, as much as the content matter, that is so unsettling. There is no opportunity to avert the eye, to focus on another portion of the image and try to alter the perspective. Unlike her early fashion shoots, these are not contrived studio sessions but are taken in the sitters’ own homes, institutions or workplaces, so that it is we who find ourselves in unfamiliar settings, alienated, confronted with people and places that may make us uncomfortable. The fact that many of her sitters appear quite at ease with their physical or mental awkwardness, or even proud of their disfigurements, challenges us to identify who it is that has the real problem.

However, not all the sitters appear comfortable with being photographed, and in the case of those with severe mental disabilities it is evident that their consent was never – and could never – be obtained. The photographer’s troubled life – after several bouts of depression Arbus committed suicide at the age of 48 – invites connections with these images of loneliness, marginalisation and suffering. Does evidence of her own unhappiness demonstrate a degree of affinity or sympathy with those she photographed? There is an honesty about her photography that undermines accusations of voyeurism or exploitation, although such charges have been made. Influential critic Susan Sontag expressed her unease about Arbus’s work in her 1973 New York Review of Books article ‘Freak Show’, which was later revised to form the central essay in On Photography (1977.) Surprisingly, for such a respected writer, Sontag never really strikes home with any critical insight about Arbus’s work. The essay is effective in articulating Sontag’s negative response, but reveals little about the photographs themselves. Her main charge – that of a lack of compassion – has ‘stuck’ nonetheless, and it is no simple matter to dismiss.

One might argue that developing a ‘lack of compassion’ is an occupational hazard for any photographer working in the documentary tradition, particularly those commissioned to record scenes of suffering in war zones or disaster areas. Maintaining a high degree of detachment is essential for professional standards: but where does one draw the line? And does the practice of enforcing such discipline not run a risk of psychological self-harm? The story of Kevin Carter (1960-94) remains a salutary warning; the life, work and death of the South African photographer was dramatised in the film The Bang-Bang Club (Steven Silver, 2010) and inspired Alfredo Jaar’s unbearably moving art-installation The Sound of Silence (2006.)

Diane Arbus’s life has also been depicted on the big screen, providing the inspiration for the film Fur (2006) directed by Steven Shainberg. Like his earlier Secretary (2002) it is an audacious portrayal of a woman’s unorthodox desires, but as a portrait of Arbus it is unsatisfactory. Those wanting to know more about her should begin by studying her photographs – and for anyone in the region of Kirkcaldy, their exhibition remains open for another month, until the end of May.

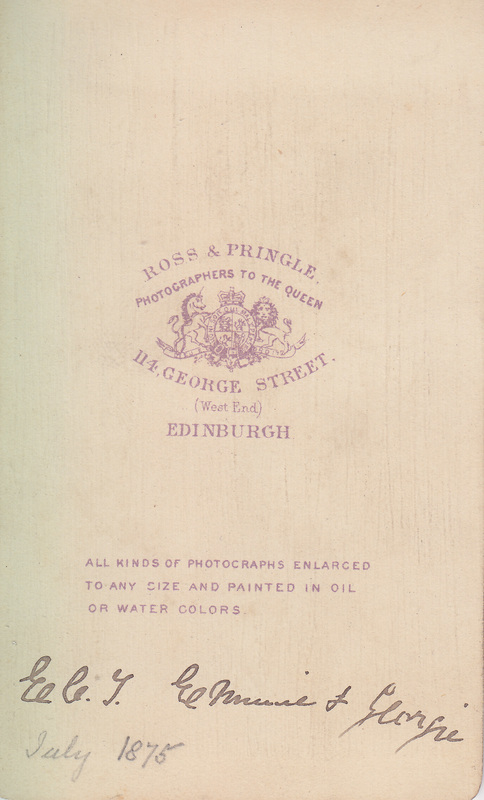

Carte de visite of the week #9 – Ross & Pringle

Continuing on the Scottish theme, this week’s cdv comes from the Edinburgh studios of James Ross (1815-95) and Thomas Pringle (died 1895), who were in partnership from 1867 until 1883.

Pringle – an assistant in the firm for many years – became Ross’s business partner following the retiral of John Thomson (born 1808/9) – not to be confused with another Edinburgh photographer named John Thomson (1837-1921) who became famous for his views of China and London street life.

James Ross was working with the calotype process when he went into partnership in 1848 with Thomson, a skilled daguerreotypist. They were appointed photographers to Queen Victoria in 1849, and later switched to using glass negatives following the introduction of collodion in the early 1850s.

James Ross has been in the news recently because of the hypothesis – advanced by American researcher Patrick Feaster – that he may have been the first photographer to produce a sequence of moving images, preceding the man usually accorded that honour – Eadweard Muybridge – by two years. Feaster’s theory is based on a reference in The British Journal of Photography, 14 July 1876, which describes a sequence of three photographs taken:

by Mr. Ross, of Edinburgh, in one of which a girl on a swing is caught just at the instant when the rope had reached the highest elevation; in another a girl is skipping, the picture showing the rope passing under her feet; while a third is that of a boy jumping over a large stone. The last is peculiarly interesting, as it was stated to be taken with a camera fitted with a number of medallion lenses, placed in threes, one above another. The exposures were made by causing a sheet of metal with a hole in it to fall so that the aperture was for an instant brought successively in front of each lens. To the lower end of the sheet was attached a heavy weight, and it was held up in such a position that the three lenses were all covered. At the proper moment the suspending thread was severed, and, although the time between the passing of the opening in the sheet from one lens to another must have been almost inappreciable, the plate showed the three pictures in very different positions.

It would appear from this passage that Ross used a single camera, but one that was specially-constructed with three lenses, allowing him to take three photographs of a moving person, animal or object in rapid succession. Muybridge used a line-up of twelve cameras to photograph a running horse in California in June 1878, with each camera activated by a trip wire as the horse passed by. His experiment was carried out to settle debate over whether a galloping horse ever had all four hooves in the air at the same time. He was able to carry out a series of trials using an array of equipment thanks to the financial support of Leland Stanford, a wealthy horse-owner and businessman. James Ross appears to have funded his own, more modest, experiments himself. For a fuller version of Feaster’s theory, see his article here.

This attractive little family group sat for their portrait around the time that Ross was working on his motion photographs, as a handwritten note on the back gives the date as July 1875 – shortly before Ross and Pringle moved from 114 George Street to 103 Princes Street. The studio was at the west end of George Street, close to Charlotte Square. The mother and her young children may have lived in the west end, but studios with a good reputation such as Ross and Pringle could attract clients from quite a distance. The only clue to their identity lies in the scribbled names and initials at the foot of the card.