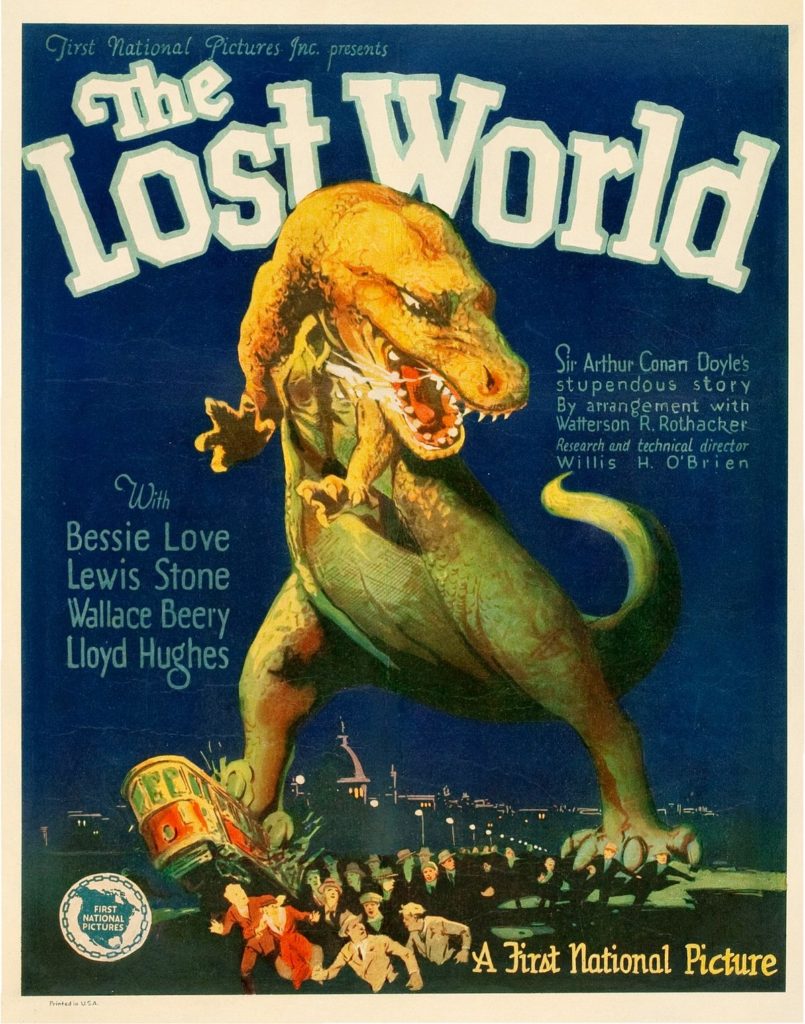

A few weeks ago I was fortunate to attend a screening of a beautifully-presented new print of The Lost World (Harry Hoyt, 1925) at Curzon Clevedon. This new (2016) restoration by Serge Bromberg’s Lobster Films runs for about 104 minutes and will almost certainly be the definitive version of the movie, restoring several fragments that haven’t been viewed for decades. (There is a rumour that existing prints of The Lost World were sought out and destroyed prior to the release of King Kong in 1933, to clear the field of any possible competition.) For many years the only version of The Lost World available was a much-mutilated 50 minute Kodascope print, but over the years successive restorations (e.g. by George Eastman House in 1998 and David Shepard two years later) introduced marked improvements in both the quality and the content, which was basically the same but with digital improvements to sound and image. It was accompanied by a new orchestral score composed by Robert Israel, which fitted the film perfectly.

A few weeks ago I was fortunate to attend a screening of a beautifully-presented new print of The Lost World (Harry Hoyt, 1925) at Curzon Clevedon. This new (2016) restoration by Serge Bromberg’s Lobster Films runs for about 104 minutes and will almost certainly be the definitive version of the movie, restoring several fragments that haven’t been viewed for decades. (There is a rumour that existing prints of The Lost World were sought out and destroyed prior to the release of King Kong in 1933, to clear the field of any possible competition.) For many years the only version of The Lost World available was a much-mutilated 50 minute Kodascope print, but over the years successive restorations (e.g. by George Eastman House in 1998 and David Shepard two years later) introduced marked improvements in both the quality and the content, which was basically the same but with digital improvements to sound and image. It was accompanied by a new orchestral score composed by Robert Israel, which fitted the film perfectly.

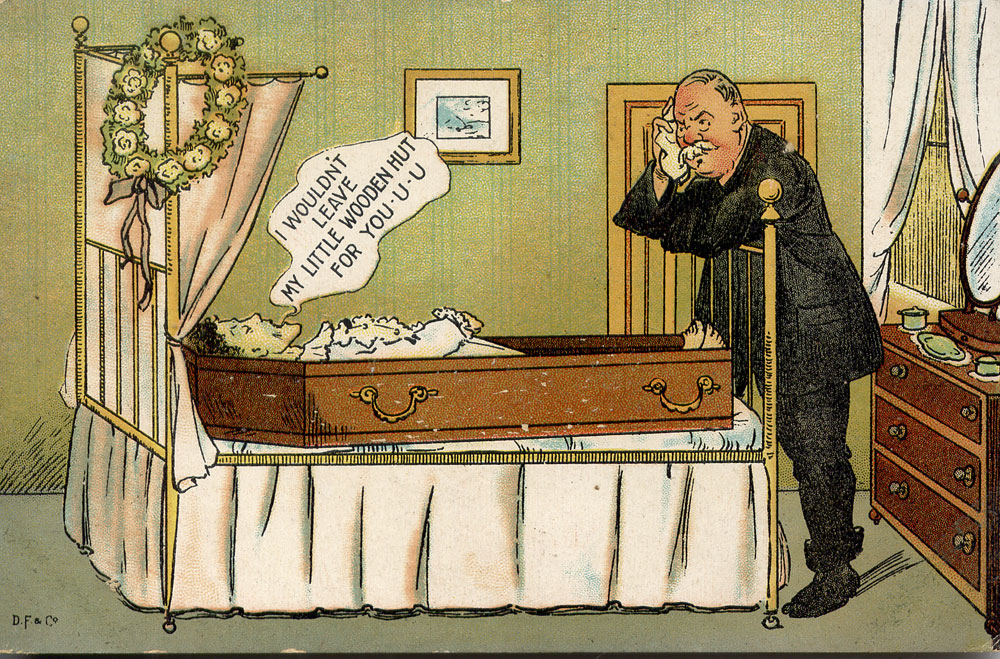

Adapted from Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel of the same name, The Lost World tells the story of an expedition led by Professor Challenger (Wallace Beery) in order to prove to his critics that dinosaurs are still living in a remote area of the Amazon jungle. Accompanying him are journalist Edward Malone (Lloyd Hughes) – whose newspaper is funding the expedition- Paula White (Bessie Love), who has a journal belonging to her missing father Maple White that contains sketches of the dinosaurs, sceptical Professor Summerlee (played by the director’s brother Arthur Hoyt) and sportsman and hunter Sir John Roxton (Lewis Stone), who has romantic feelings for Paula. The film follows their exploits in the jungle, encountering dinosaurs, learning what happened to Maple White, escaping from volcanoes and ape-men, transporting a brontosaurus back to London – and of course dealing with its inevitable escape and rampage through the city streets….

Thus particular screening was introduced by Peter Lord, cofounder of Aardman Animation. He also brought along some of the original models used in making their latest stop-motion film Early Man.

Stop-motion models for ‘Early Man’ (2017)

The growth of Aardman – from a domestic tabletop to a world-leading Oscar-winning studio – echoes the remarkable career paths of early animators such as The Lost World’s Willis O’Brien, who went on to work on King Kong, a film that inspired a young Ray Harryhausen to become O’Brien’s assistant. Aardman are perhaps best known now for Nick Park’s Wallace and Gromit films but those of a certain generation will remember the animated character ‘Morph’ who first appeared on BBC’s Take Hart in the late 1970s.

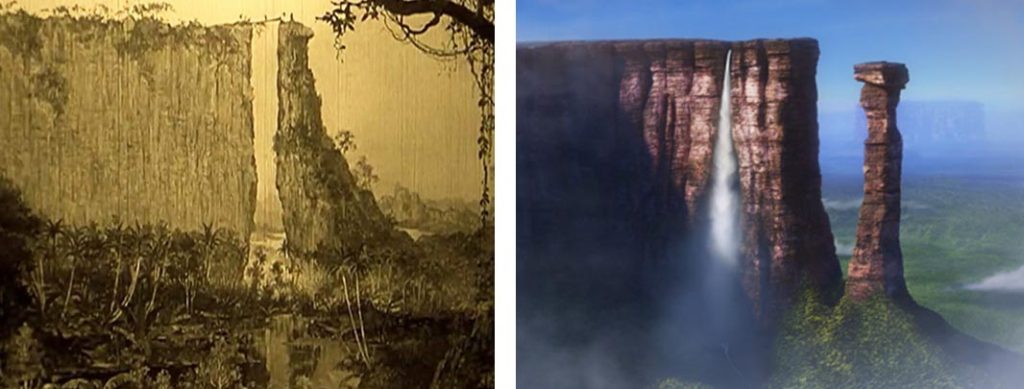

The setting for Paradise Falls in Pixar’s animated movie ‘Up’ (Docter, 2009) was clearly inspired by the cliffs in ‘The Lost World.’ The American company Pixar was associated with Lucasfilm and Apple before being bought by Disney. Unlike Aardman, stop-motion techniques have played little part in Pixar’s computer-generated animation.

The influence of The Lost World and King Kong on 20th century cinema has been enormous, and can be traced through numerous films including Hammer’s prehistoric movie cycle, the Jurassic Park franchise and other fantasy adventures. Ray Harryhausen’s work has inspired generations of animators and film-makers, yet the name of the man who inspired him is often forgotten now. Before the main feature we were treated to one of O’Brien’s earlier films, a short five-minute film R.F.D. 10,000 B.C. made for Thomas Edison’s company in 1916. This was accompanied by live music played on the Curzon’s organ by Colin Godfrey. The plot, for what it was, followed two cavemen competing for the love of a cavewoman, one a postman who used a dinosaur to carry his mail (R.F.D. stands for ‘Rural Free Delivery’, the American postal service for farms and rural settlements.)

For those who have not yet seen the restored version of The Lost World – and it’s far superior to the truncated versions shown previously on television – it is being screened as part of the Ilfracombe Film Festival on Saturday 21st April at 4 pm in the Landmark Theatre, on Ilfracombe’s Promenade. You won’t be disappointed!