Category Archives: Art

Haldane Macfall’s Whistler

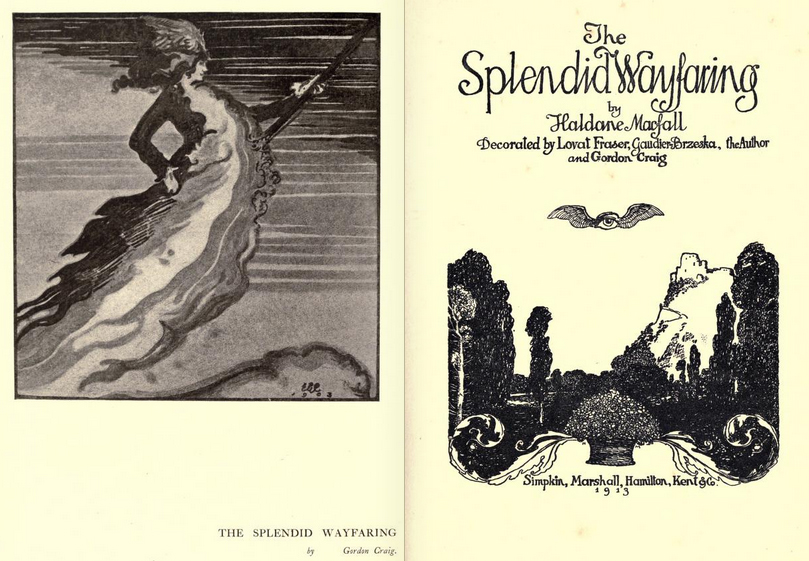

Macfall’s literary career began while serving in Africa with the West India Regiment in the 1880s, when he began writing about his experiences for The Graphic. A skilled artist, he also contributed illustrations to the magazine, designed bookplates, decorated books and exhibited at the Royal Academy.

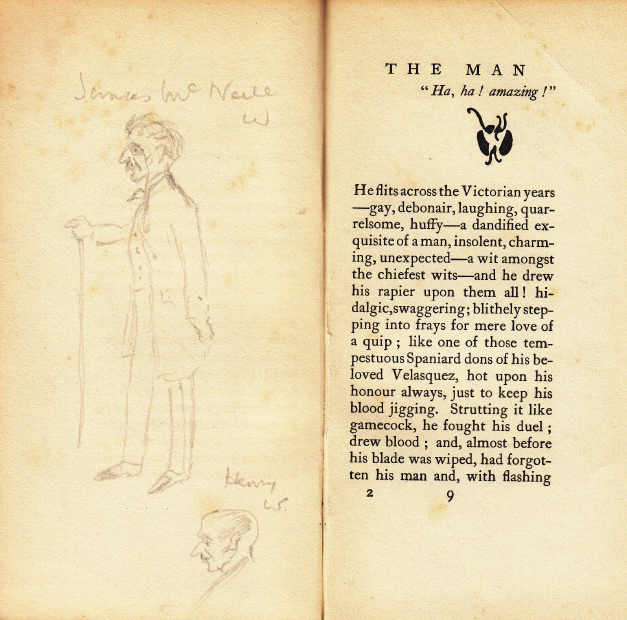

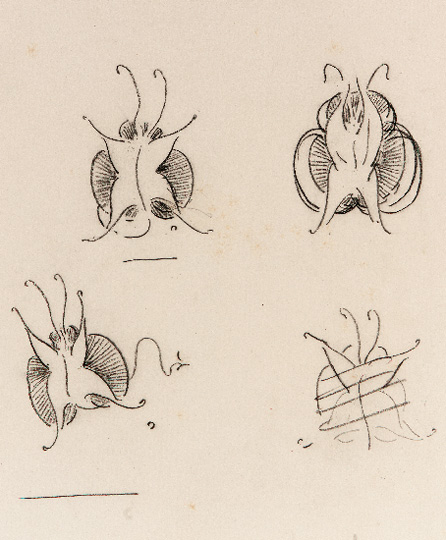

Quite apart from my interest in Whistler, I was attracted to the book’s design and page layout, and particularly intrigued by the presence of hand-drawn pencil sketches opposite the opening page.

There is nothing here to identify the artist, although there seem to be quite a few copies of Macfall’s books in circulation bearing pencil sketches on their blank pages.

Chambers Haldane Cooke Macfall was born in 1860 but lost his mother when he was still young. His father Surgeon-Major David Chambers McFall (1833-98) remarried in 1871, and his new bride – Frances Clarke – became stepmother to Haldane and his brother Albert. At sixteen, Frances was only six years older than her eldest stepson, and within a year she gave birth to a boy named Archibald. The Macfalls spent five years in the Far East, returning to England in 1876, but the marriage proved an unhappy one. Frances left her husband in 1890, subsequently changing her name to Sarah Grand.

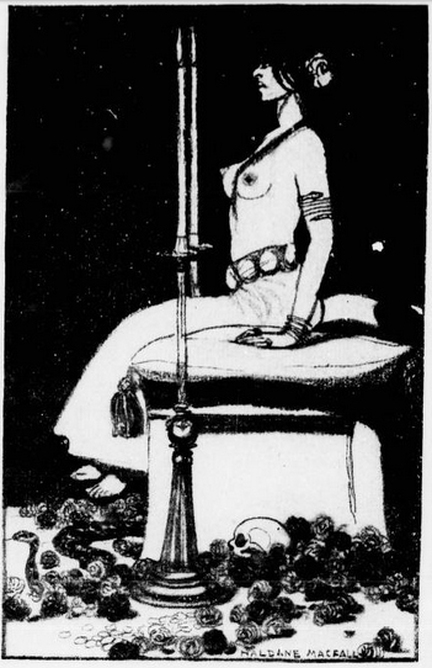

Sarah was a forceful campaigner for women’s rights and a prolific writer of both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Heavenly Twins (1893) sold over 20,000 copies and caused some controversy due to its strong feminist message and frank treatment of medical matters relating to sexual behaviour. She was active throughout the 1890s, lecturing on topics such as women’s suffrage and rational dress. In 1898 Haldane McFall moved in with his step mother, having been forced to leave the army due to a serious bout of fever. His first novel The Wooings of Jezebel Pettyfer was published the same year. His next novel, The Masterfolk (1903) was a witty portrait of Bohemian life in London and Paris in the 1890s, declared by Vincent Starrett – in his essay on Macfall in Buried Caesars (1923) – to be ‘the last word on the English decadents.’ Other novels include Rouge (1906) and The Three Students (1926), while his biographies included Ibsen: The Man, His Art & His Significance (1903), Sir Henry Irving (1906), Fragonard (1909), Boucher (1911) and a spirited defence of his friend Aubrey Beardsley (1928.) He returned to the army to serve during World War One, and published a number of books and essays on military topics. He collaborated several times with the artist Claud Lovat Fraser, who – along with Edward Gordon Craig – provided illustrations for Macfall’s essay on art and aesthetics, The Splendid Wayfaring (1913.) Macfall seems to have been on friendly terms with both artists. Gordon Craig’s father had been a friend of Whistler’s, and he was godson of another of Macfall’s biographical subjects, Henry Irving. He engraved bookplates for both Macfall and his wife Mabel, and wrote an appreciation of Macfall after his death.

Whistler exercised a considerable influence on the aesthetic movement in Britain – not only through his artwork, but also by his insistence on the autonomy of art, which he believed existed for its own perfection rather than for didactic purposes. Wilde had made a similar argument during his 1895 trials, and Whistler also found himself defending the notion in court during the libel case that followed Ruskin’s slur on the artist’s Nocture in Gold and Black. By contrast, Whistler’s response to reading some of Macfall’s art criticism was apparently ‘Ha ha, this man knows.’ It was probably just as well that he found nothing to offend, for Whistler made a formidable enemy – the waspish wit collected in The Gentle Art of Making Enemies (1890) may amuse readers, but being on the receiving end of Whistler’s wrath was far from pleasant.

This aspect of Whistler’s work was symbolised in the butterfly monogram that appears on the cover of Macfall’s book and elsewhere inside. The artist used this on his paintings in place of a signature from 1869 onwards, basing it on his initials ‘J.W’ but developing a series of variations over the years. When using the monogram to sign his more acerbic correspondence, he would give the butterfly a stinging tail.

In Fairyland

At Barnstaple pannier market a while ago I came across this old framed print and – after circling the stall several times – succumbed to temptation. The illustration is taken from the book In Fairyland: A Series of Pictures from the Elf World (London: Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer, 1870) and was the work of Punch illustrator Richard Doyle (1824-83.)

The artist was of one of the seven children of political cartoonist John Doyle (1797-1868), whose artistic skill was inherited by his four sons Richard, James, Henry and Charles (father of Sherlock Holmes author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.) Of the four, Richard Doyle had the most successful career, and his early talent found him a place on the staff of Punch magazine when he was only nineteen. It was he who devised the famous image of the Punch cartoon character that adorned the magazine’s front cover from January 1849 until October 1956, replacing his earlier cover (January 1844) that featured crowds of elves and fairies.

Doyle’s talent for fairy drawings was first made public in 1846 with his artwork for The Fairy Ring (a new translation of Grimm’s tales), followed in 1849 by his illustrations for Fairy Tales from All Nations and Punch editor Mark Lemon’s The Enchanted Doll. He clearly relished the subject matter, and his skill in depicting pixies, elves, fairies and other fantastical creatures attracted commissions for a series of other fantasy titles such as The Story of Jack and the Giants (1850), and John Ruskin’s The King of the Golden River (1850), which went through three editions in its first year of public.

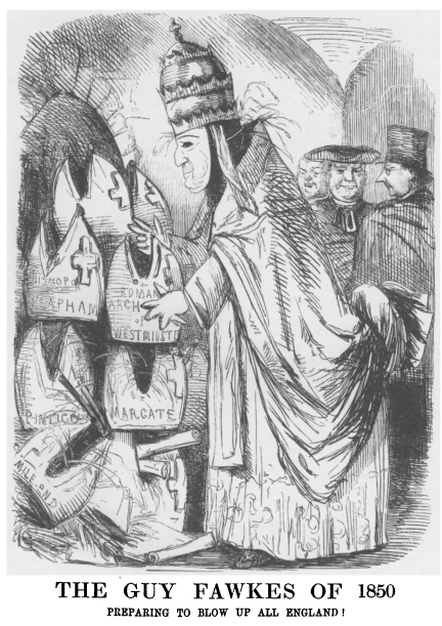

Another publication in 1850 had important consequences for Doyle’s career, however.

Doyle came from a devout Irish Catholic background and found himself increasingly unable to reconcile his faith with the magazine’s trenchant anti-Catholic stance. After the above cartoon appeared in November 1850, Doyle resigned from Punch. Over the next few years he undertook book illustration work for Thackeray and Dickens, before finding a new sense of purpose when he returned to his fairy artwork in the late 1860s.

This was by no means unusual at a time when fairies inhabited nearly every nook and cranny of Victorian literary and artistic culture. Their popularity raises some intriguing questions for a society that saw strident advances in industrial technology, and seemed proud of the victory of scientific progress over naive superstition. One wonders if the colourful jewel-like fairy world offered a sense of hope, an antidote, or the possibility of escape, when set against the rapid expansion of sprawling, smoking cities and the loss of rural traditions. Great artists – including Royal Academicians – recorded their fantastical visions of fairy lore on huge canvases, with the same painstaking precision and technical virtuosity applied to serious landscapes and religious subjects.

Here is just a small selection:

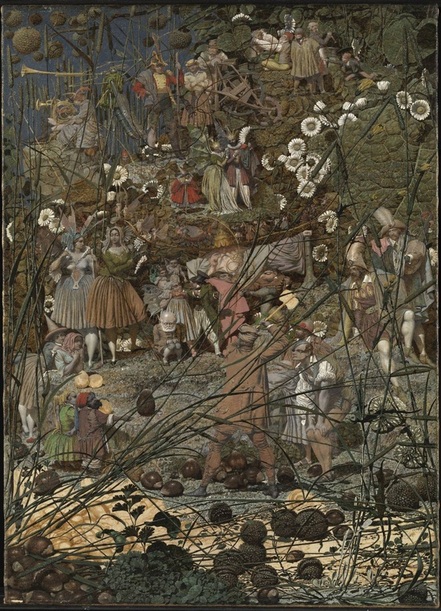

Richard Dadd The Fairy-Feller’s Master Stroke

Richard Dadd The Fairy-Feller’s Master Stroke

The artist worked on this painting between 1855 and 1864 when he was transferred from Bethlem Hospital to Broadmoor.

It is to this tradition of Victorian fairy painting that Richard Doyle’s In Fairyland belongs. Although dated 1870 on the title page, it was actually published in time for Christmas 1869. The folio was richly bound in green cloth, cost over 30 shillings, and has been described as one of the finest examples of Victorian book production. There are 16 colour plates – of which this my picture is the last – and 36 line drawings. Doyle was given free rein to design his own illustrations, which were later re-used in Andrew Lang’s The Princess Nobody (1884.)

Each plate was accompanied by a verse written by Irish poet William Allingham (1824-89), whose wife Helen was a skilled watercolourist and illustrator. That for Plate XVI reads:

Asleep in the moonlight. The dancing Elves have all gone to rest; the King and Queen are evidently friends again, and, let us hope, lived happily ever afterwards.

I have hung the picture on my study wall, between an oil painting of my childhood home and a line drawing of the cottage in which I now live. It seemed an apt place for the fairies to sleep.

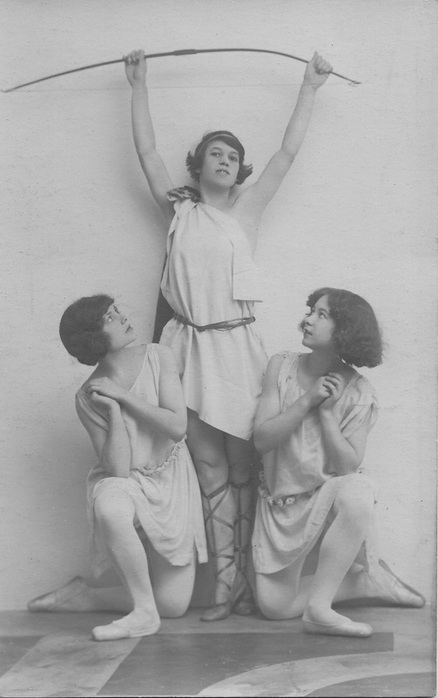

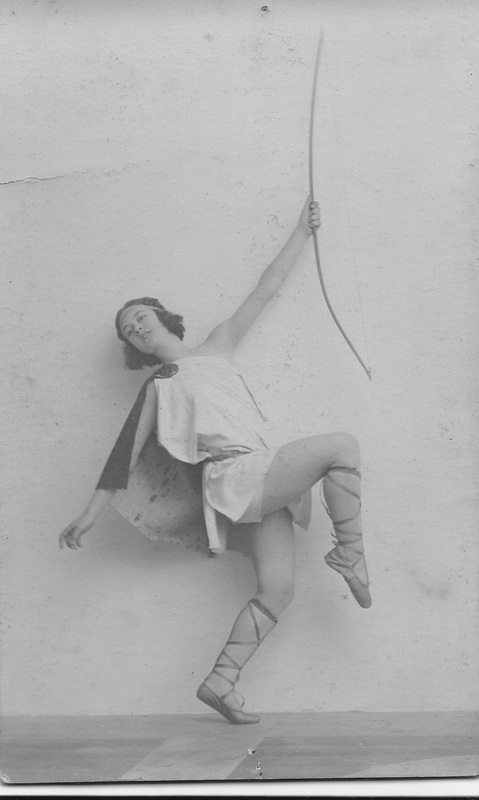

The Fair Toxophilite – dance photographs from the school of Madame Espinosa

Some time ago I came across a little bundle of photographs in a basket at an antique shop, and after rummaging around, found some other pictures depicting the same dancer. Here is a selection.

Madame Judith taught formal ballet, but the classical costumes – along with some of the dancers’ poses – seem to me to evoke the style of Isadora Duncan or Margaret Morris.

The school was in London, although one of the dancers also appears in an old photographic postcard from the studio of John Robert Pearce in Exeter, which suggests a Devon connection. Are there any former students of Madame Espinosa still out there?

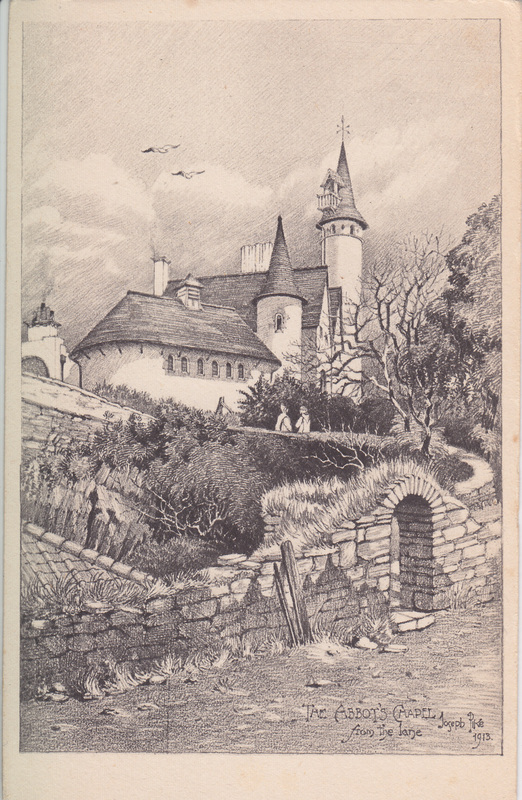

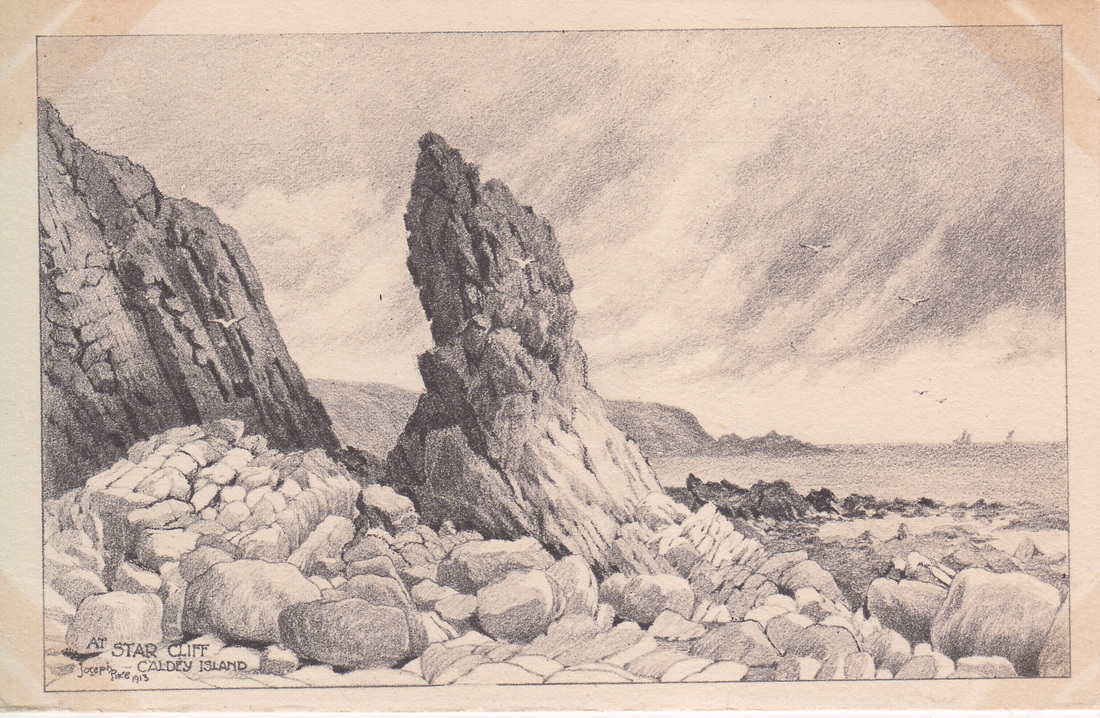

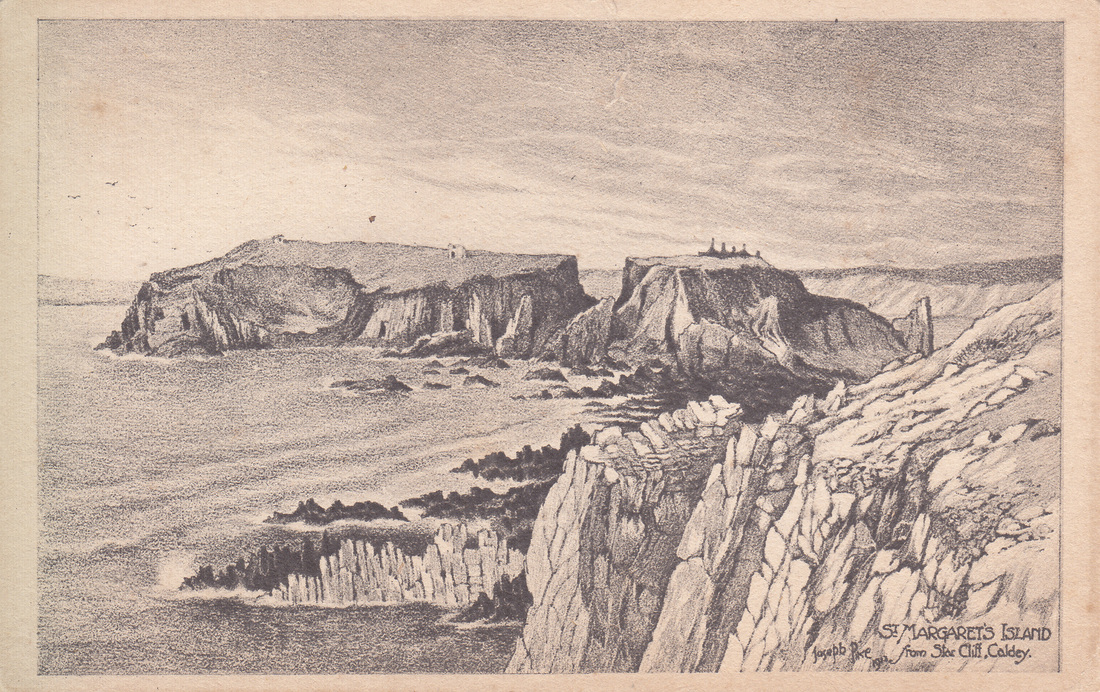

Caldey Island, 1913 – postcards by Joseph Pike

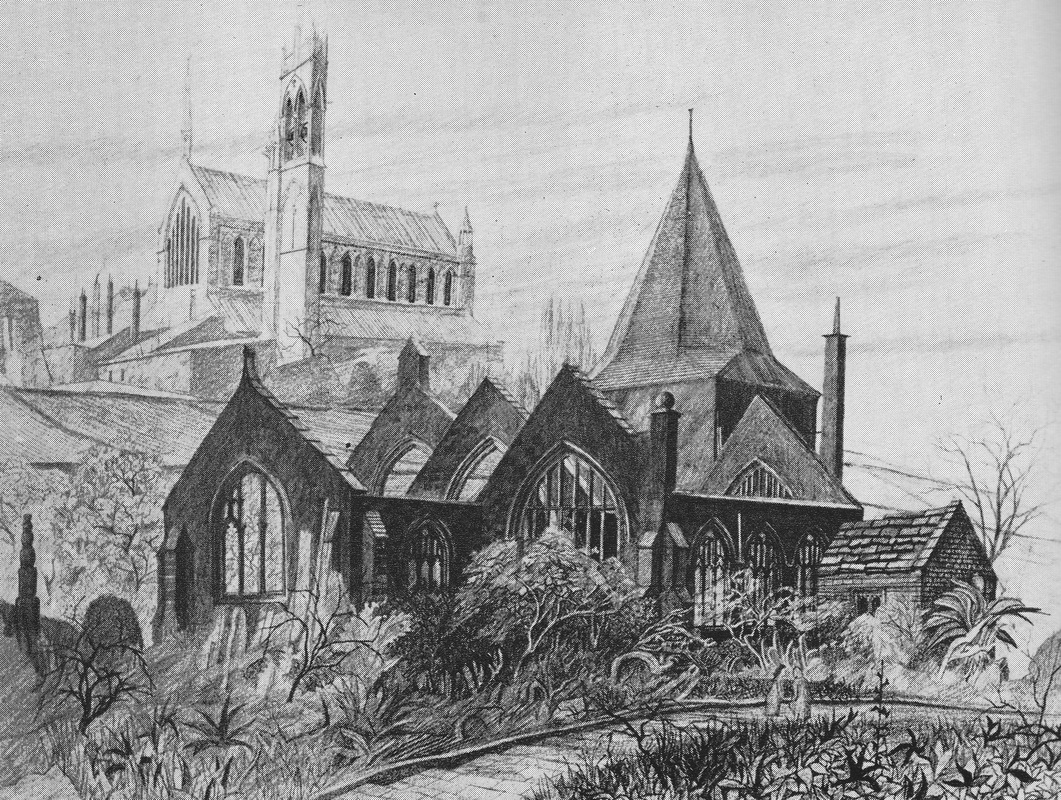

Caldey Abbey & Priory Bay

Caldey Abbey & Priory Bay

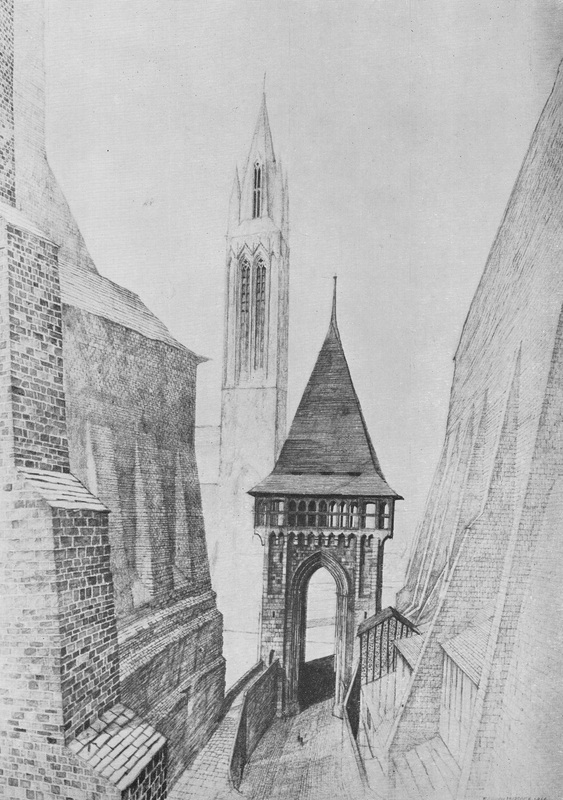

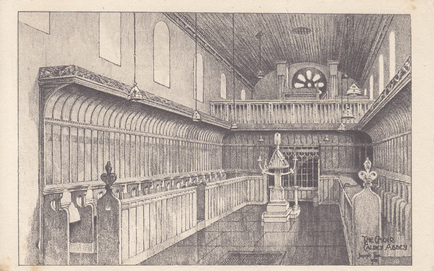

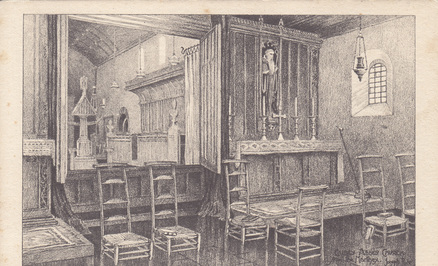

Caldey Abbey Church from the Narthex

Caldey Abbey Church from the Narthex

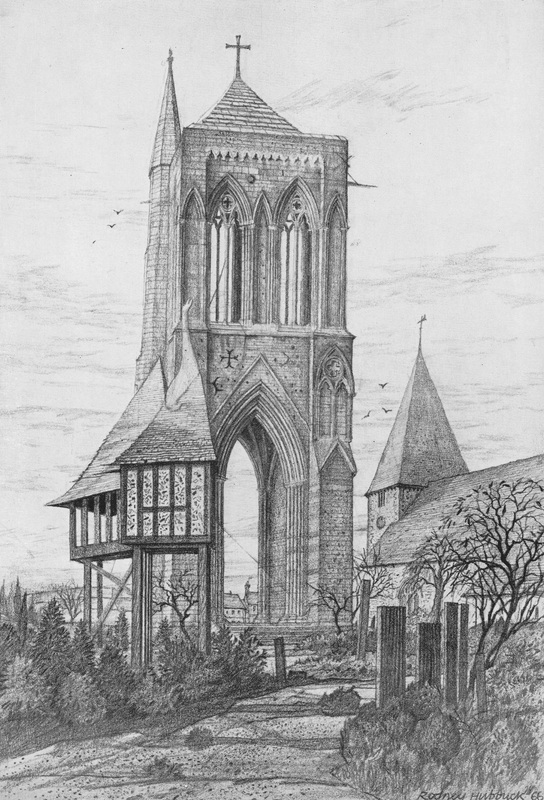

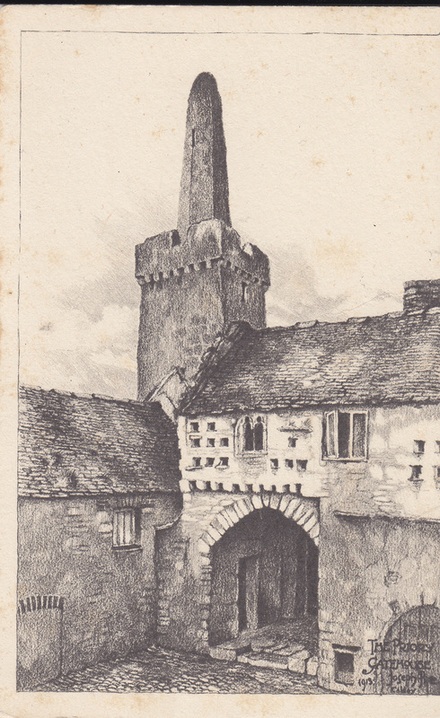

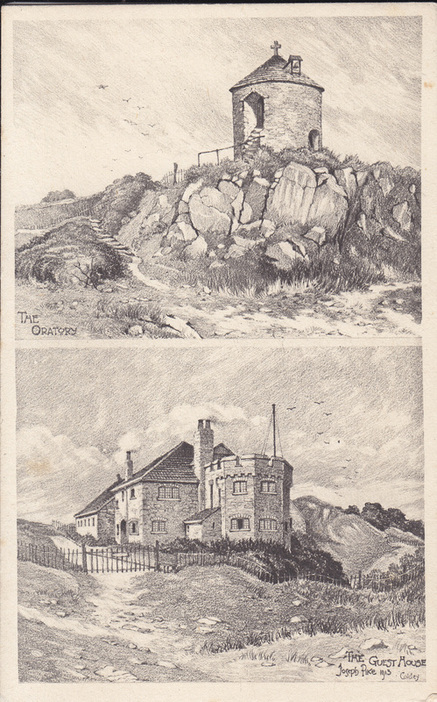

Pike’s interest in church interiors is evident from these pictures, as is his care in rendering precise details of architecture and metalwork. His great break came when he was asked by the Benedictine historian Bede Camm O.S.B. to provide illustrations for Forgotten Shrines (London: Macdonald & Evans, 1910). In his Preface, Father Bede wrote: ‘I feel a very special debt of gratitude to my artist, Mr Joseph Pike, for the very beautiful drawings with which he has illustrated and adorned the text. Mr Pike is still a young man, and there can be no doubt as to his great talent.’

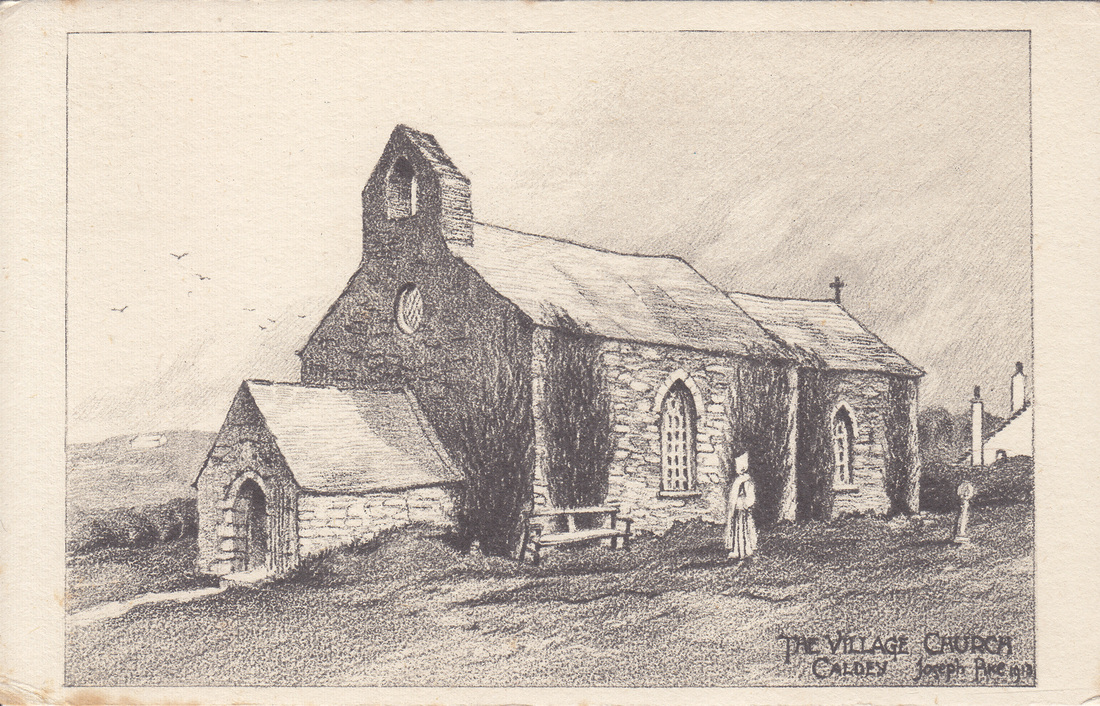

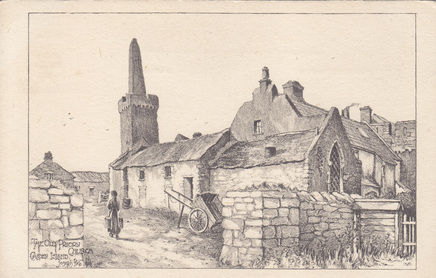

The Old Priory Church, Caldey Island

The Old Priory Church, Caldey Island

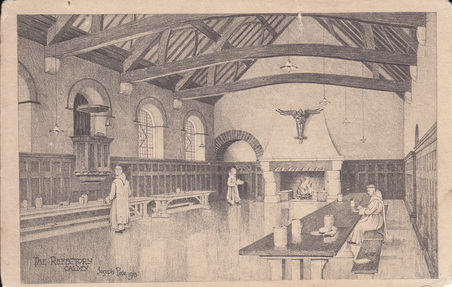

Caldey Island was at this time home to a community of Anglican monks under the leadership of Aelred Carlyle. I have written about this community elsewhere – there are references below under the Monk and His Movies blog post, and it is interesting to compare Peter Anson’s line drawings with Joseph Pike’s more nuanced depictions of textures and shading.

Carlyle’s attempt to introduce Benedictine monastic life to the Church of England placed him and his community on a collision course with the Anglican authorities, particularly with regard to liturgical rites and ecclesiastical obedience. Matters eventually came to a head in 1913, resulting in almost the entire community being received into the Catholic Church. This took place 101 years ago today – 5th March 1913, the day before Joseph Pike’s thirtieth birthday.

Bede Camm had followed events on Caldey for some years, defending the community in a letter to the Catholic Times in 1905. He landed on the island on 28 February and said Mass in the monastery chapel – probably the first time this had been done since the Reformation. After the conversion, he became novice master to the monks. It was presumably through his involvement with the Caldey community that Joseph Pike visited the island to carry out these drawings.

The Oratory (top), The Guest House (bottom), Caldey

The Oratory (top), The Guest House (bottom), Caldey