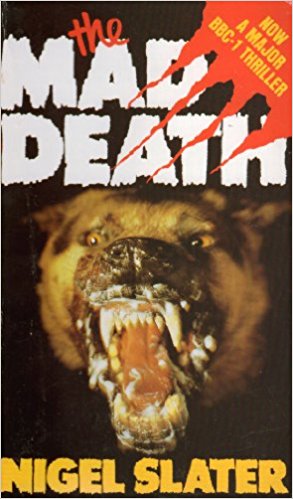

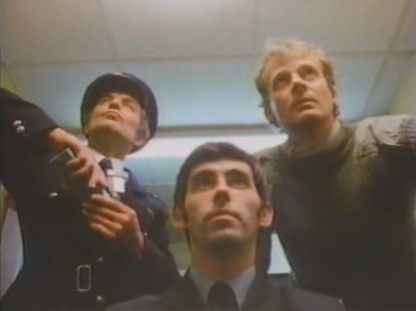

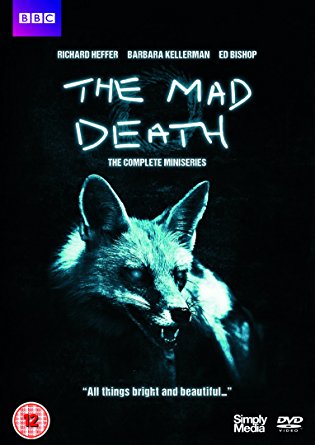

On 7 May the BBC finally released a DVD of The Mad Death, some 25 years after the miniseries was originally broadcast in the summer of 1983. The programme imagined what might happen if rabies was introduced into Scotland, and over the course of three episodes follows the spread of the disease, its effect on victims, and the authorities’ attempts to control the outbreak. Filmed on location around central Scotland – including a memorable chase sequence in which a landrover pursues a rabid dog through the old Plaza shopping centre at East Kilbride – and containing some horrific scenes of rabies symptoms, including nightmarish hallucinations – the programme attracted a great deal of attention at the time, especially as the threat of rabies reaching the UK was a real fear then, and the subject of widespread media campaigns.

In retrospect, one wonders if we worried too much, and over the years my memories of watching the original broadcast have been tempered by further reflection about the other fears and anxieties that perhaps lay beneath all the lurid imagery and ‘protect our borders’ propaganda.

The BBC’s timing of their DVD release was rather serendipitous as it coincided with the publication of my illustrated article, ‘”Mad Dogs and Englishmen”: Hydrophobia, Europhobia and National Identity in “The Mad Death” (BBC Scotland, 1983)’ in the online periodical, The International Journal of Scottish Theatre and Screen. This was written for a special issue on ‘TV in Scotland: Past, Present and Future’, and some idea of the contents can be gleaned from the abstract:

BBC Scotland’s three-part series The Mad Death (1983) presented a fictional account of a rabies outbreak on Scottish soil. Although the story was based on a lurid unpublished novel and made use of classic horror tropes, including animal attacks, imprisonment in a baronial manor and terrifying hallucinations, it also reflected the sober tone of public information films and contemporary rabies safety campaigns. Filmed in Scotland and making effective use of Highland locations and actors such as Jimmy Logan, the ‘Scottishness’ of the production was nonetheless undermined by the vague presentation of the physical landscape, uncertainty over the parameters of the Scottish and English authorities, and an uneven depiction of social classes and dialects. A more detailed study of this content reveals the cultural anxieties that underpinned the narrative and characterisation, which remain acutely relevant as the 35thanniversary of the original broadcast approaches. Drawing on original production materials and personal discussions with screenwriter Sean Hignett, this article places The Mad Death in its social, cultural and political context, exploring how the series engaged with questions of national heritage and social identity while at the same time repackaging familiar tropes from the traditions of the horror genre. Particular attention is applied to the ways in which the spread of rabies is used to reflect anxieties about the dangers of European integration, employing language and attitudes that are all too familiar from the ongoing ‘Brexit’ debate in Britain. Through a close analysis of these issues it is possible to provide detailed insights into the production of The Mad Death, the adaptation process and the workings of the Scottish television industry during a time of social and political upheaval. The essay aims at providing a case study from which lessons can be learned that could help guide policy for future Scottish programming.

and also from a little ‘word cloud’ image that I generated:

For those who wish to read my article, it can be accessed (free-of-charge) here