Today sees the premiere of Jurassic World, the fourth installment of the lumbering prehistoric franchise that seems to have become a permanent fixture of weekend television. When I saw the trailer I had a sense of déja vu – not simply with regard to myself, but also for the characters: does the basic premise not ring any alarm bells with anyone visiting a theme park with live dinosaurs? Has no-one learned anything? Anyway, the trailer was so laden with CGI that I found myself hankering for prehistoric hokum from an earlier era, and have therefore been feasting on some old Hammer dvds.

The name of Hammer will always be associated with the horror genre, but the studio’s output also included science-fiction, thrillers and comedies. During a short period in its history Hammer also turned their focus on the prehistoric era, resulting in four films: One Million Years B.C. (1966), Slave Girls (1967), When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970) and Creatures the World Forgot (1971.) Compared to the contemporary Jurassic franchise, these movies might appear as antiquated as the period in which they are set, but they provide entertainment in areas that Spielberg left untouched.

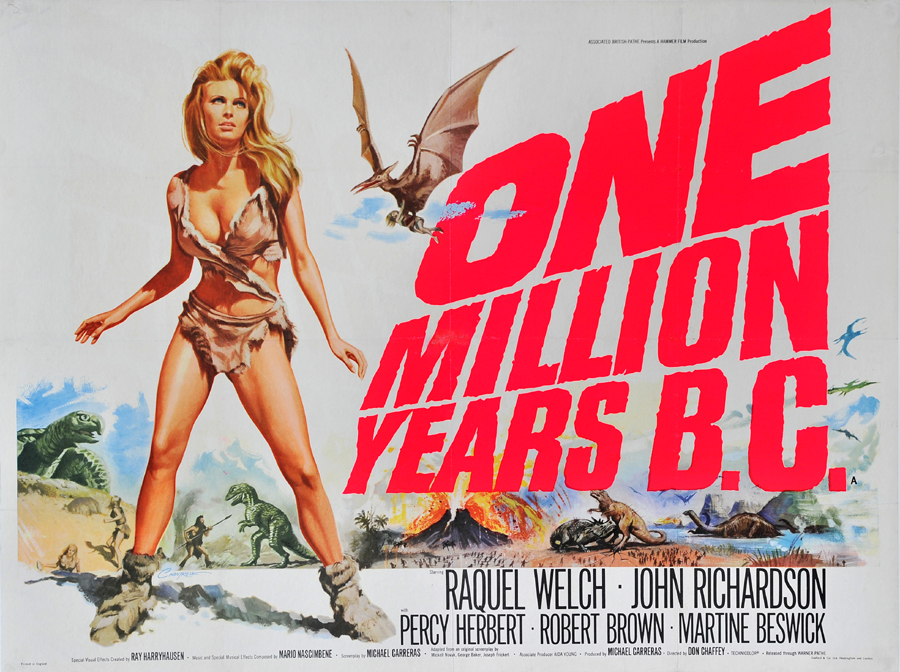

1. One Million Years B.C.

(Don Chaffey, 1966)

The movie is actually a remake of One Million B.C. (Hal Roach, 1940) which starred Victor Mature as Tumak and Carole Landis as Loana – parts played in the Hammer film by John Richardson and Raquel Welch respectively. Tumak is the son of Akkobo, chief of a dark-haired and savage tribe known as the Rock People. He is cast out from his people after a squabble over who gets to the eat the biggest chunk of meat, and after surviving a series of dangers, is rescued by the lovely Loana from the more civilised Shell People. Tumak’s rough ways are gradually softened by living with the new tribe, but the prospect of peace is threatened by skirmishes with the Rock People, dinosaur attacks and a volcanic eruption.

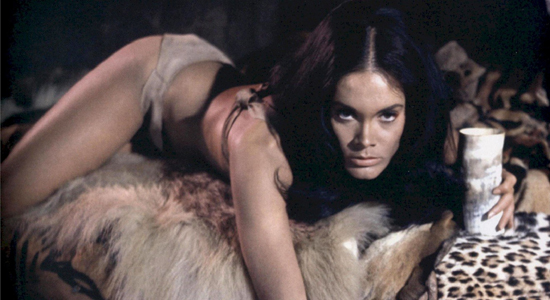

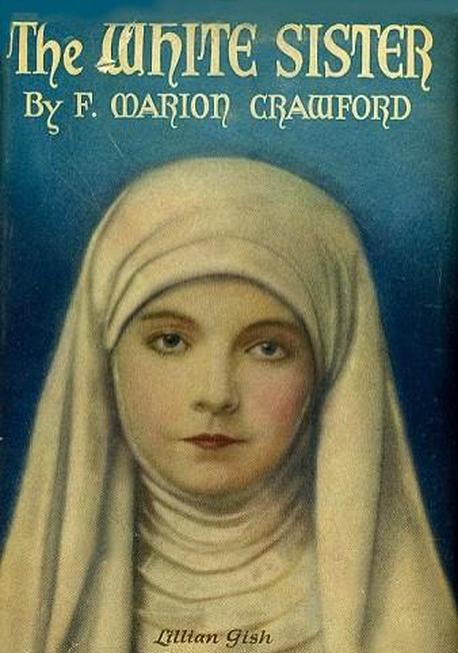

Rather than using the costly stop-motion process to depict his dinosaurs, director Hal Roach used magnified footage of live reptiles wearing stick-on fins and horns. Ludicrous although it sounds, the effects were actually so good that they were re-used in several other films such as Tarzan’s Desert Mystery (Wilhelm Thiele, 1943), Two Lost Worlds (Norman Dawn, 1951) and Valley of the Dragons (Edward Bernds, 1961.) The most iconic image from the film is, of course, that of Racquel Welch in her fur bikini; it would be a dreadful sin of omission if I failed to include a picture.

The 1966 movie sticks fairly closely to the story of the original, but for the dinosaur scenes they turned to Ray Harryhausen, whose stop-motion animation technique has recently been used in Jason and the Argonauts (Don Chaffey, 1963) and First Men on the Moon (Nathan Juran, 1964.) Some live action sequences – involving a magnified iguana and tarantula – were also included as a nod of respect towards Hal Roach’s movie.

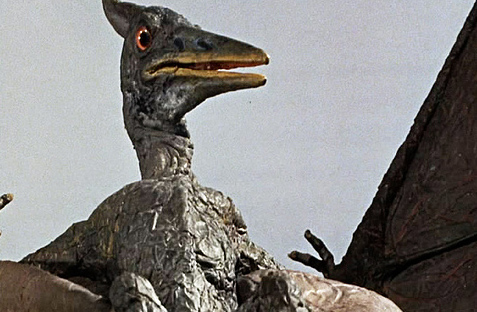

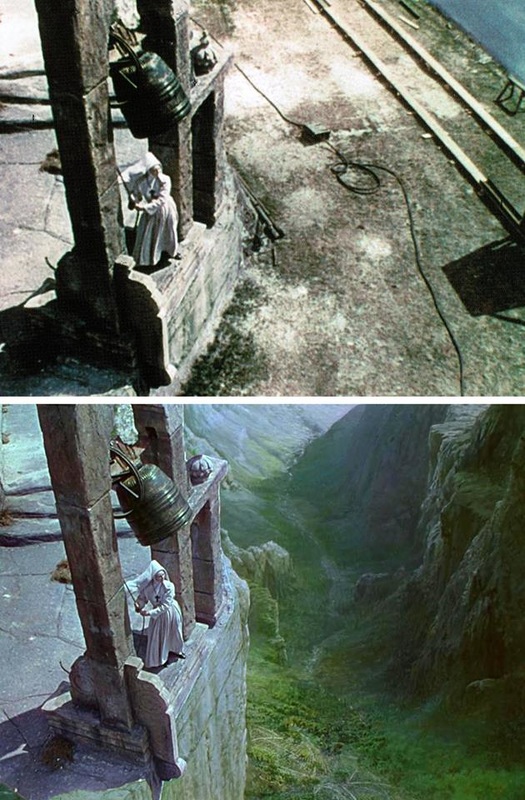

Highlights include a battle between a tyrannosaurus rex and a triceratops, an attack on the settlement by an allosaurus, where a young girl is stranded up a tree, Loana being carried away by a pterosaur or flying lizard (below.)

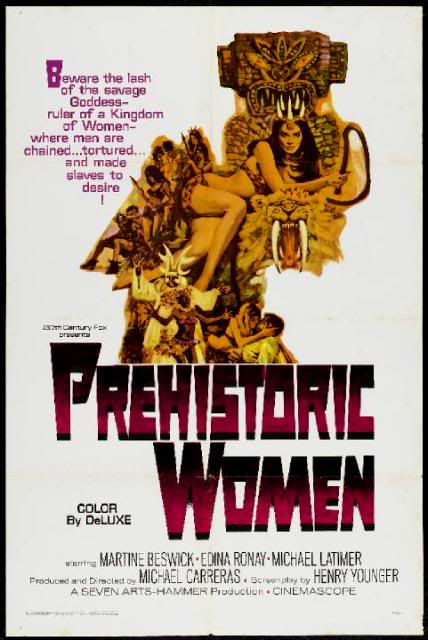

2. Slave Girls/ [In U.S. – Prehistoric Women]

(Michael Carreras, 1967)

As executive producer of Hammer Films from 1955, Michael Carreras was the driving spirit behind much of the studio’s output over the next two decades and was the producer of all four films featured here. Slave Girls (released in America as Prehistoric Women) is, however, the most ridiculous of the quartet, and studio executives were well aware that it was a sub-standard effort. It was shot in four weeks, re-using sets and costumes left over from One Million Years B.C. – a cost-cutting tactic frequently used by Roger Corman for his B-movies.

The script is far-fetched, to say the least. Big-game hunter David Marchand (Michael Latimer), has been captured by African tribesmen and is about to be sacrificed when a time portal opens up and transports him back to a prehistoric world populated by two tribes of women – one blonde, the other brunette. The latter are the dominant tribe, headed by Queen Kari (Martine Beswick), and the poor blondes – who happen to be rhino-worshippers – live in a state of slavery, while the men are imprisoned in a dungeon. Marchand’s arrival makes things worse, especially when he falls for blonde slave girl Saria (Edina Ronay). Whether these are prehistoric slave girls or merely women in a jungle somewhere is never resolved, and there is even a hint that the entire episode may have been some sort of dream after Marchand passes out.

Despite the absurdity of all this, Martine Beswick delivers an impressive performance as the imperious Queen Kari. A less dignified scene sees her recreating her catfight with Raquel Welch in One Million Years B.C., this time with Carol White, whom sharp-eyed viewers might remember as the young Sibella in Kind Hearts and Coronets (Robert Hamer, 1949) – she was soon to receive great acclaim in the role of a homeless single mother in Cathy Come Home (Ken Loach, 1966.) Beswick went on to appear in From Russia with Love and Thunderball, but her Bond girl roles were really a step down from Queen Kari.

In many UK cinemas Slave Girls was screened as a double bill with The Devil Rides Out (Terence Fisher, 1968)

3. When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (Val Guest, 1970)

The movie is underpinned once again by rivalry between blondes and brunettes. A dark-haired tribe are about to sacrifice a group of blonde victims as an offering to protect them from dinosaur attacks, when a freak storm (apparently to do with the creation of the moon) disrupts the ceremony. One of the blonde women, Sanna (Victoria Vetri) escapes by plunging off the cliff into the sea, from which she is rescued by members of another tribe – including Tara (Robin Hawdon), whose affection for her rouses the jealousy of his ‘wife’ Ayak (Imogen Hassall.)

The hostility of Ayak is just one of the difficulties faced by Sanna – she has to fend off dinosaur attacks, escape from giant snakes and carnivorous plants, while the priest (Patrick Allen) from whom she escaped at the start comes looking for her and manages to convince her rescuers that she is responsible for their misfortunes. Everything comes to a head on a beach, just as a tsunami prepares to roll in – one of many scenes in which the laws of nature appear to have been suspended.

The film follows the same structure as One Million Years BC, and the caveman ‘language’ is used much more extensively – which does become tedious rather quickly. There is some effective handheld camera work and intriguing scenes, such as one where we see one of the Beach Tribe women applying tar to young girl’s blonde hair.

Highlights include a beach attack by a plesiosaur, a battle with a triceratops-like chasmosaurus , a delightful baby dinosaur and its less delightful mother, and another flying lizard snatch.

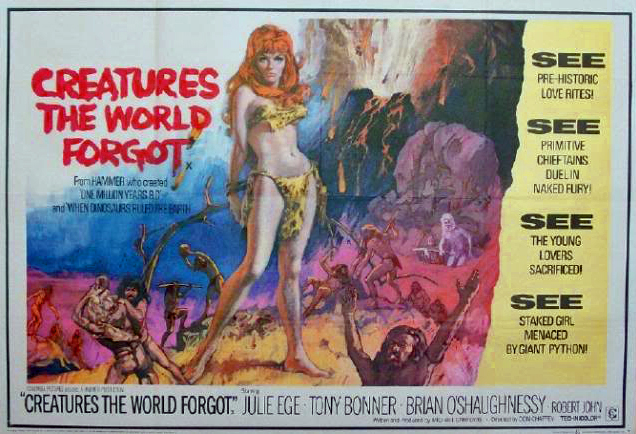

4. Creatures the World Forgot

(Don Chaffey, 1971)

The title is slightly misleading, as the reference to creatures raises some expectation of more dinosaurs, but alas, the movie is devoid of prehistoric monsters and instead provides another tale of rivalry between dark-haired and fair-haired tribes. This conflict is personalised when a woman gives birth to twin sons, one blond (Toomak) and the other dark-haired (Rool); recalling Biblical tales of Cain and Abel or Jacob and Esau, the two grow up as rivals, the situation exacerbated when Toomak is given the hand of Nala (Julia Ege), daughter of a tribal chief. We do get to see a sabre-toothed tiger and a python, but despite the presence of former Miss Norway, Julia Ege, the film is more concerned with cavemen rather than women, whose dialogue consists of grunts that are even less eloquent than the prehistoric ‘dialect’ used in the previous film. It may be just as far-fetched as the films outlined above, but there is a sense with Creatures the World Forgot that Hammer was making a stab at realism: the world depicted here is certainly a more plausible than one in which dinosaurs and humans romp about together. There are some interesting depictions of folklore rituals involving masks and talismans, and the film makes the most of the location shots in Namibia, incorporating footage of native wildlife.

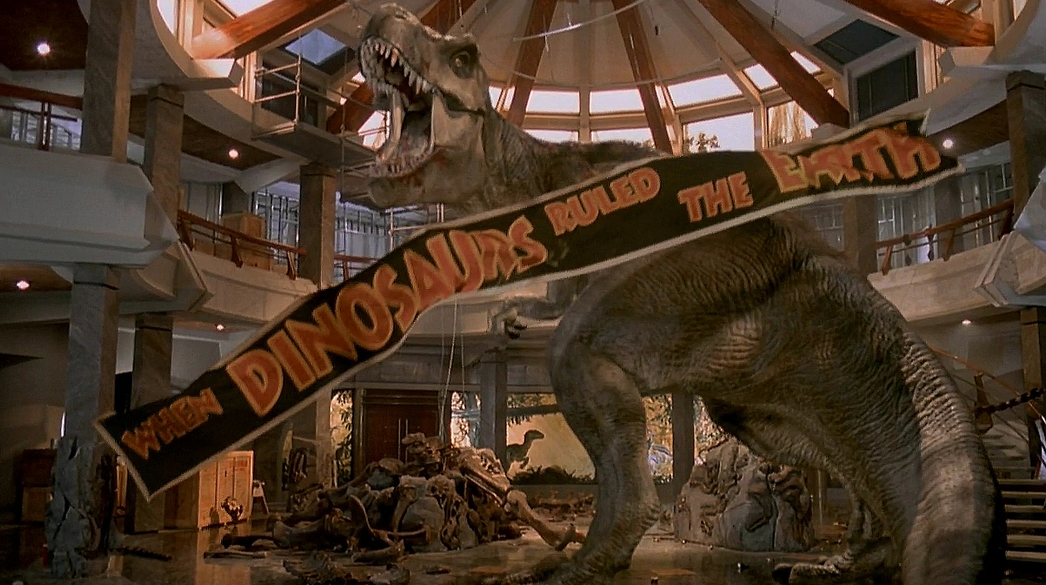

The influence of these films is discernible upon subsequent prehistoric romps such as The Land That Time Forgot (Kevin Connor, 1975) its sequel The People That Time Forgot (Kevin Connor, 1977) and the totally anachronistic nonsense of 10,000 BC (Roland Emmerich, 2008) whose time-specific title must surely be a respectful nod towards the earlier Hal Roach/Hammer movies. Although they have managed to move away from the sexist and racist overtones of the Hammer era, the Jurassic Park franchise continues to indulge audiences’ desire to see humans and dinosaurs on screen together, and they even make a direct allusion to the earlier movies: