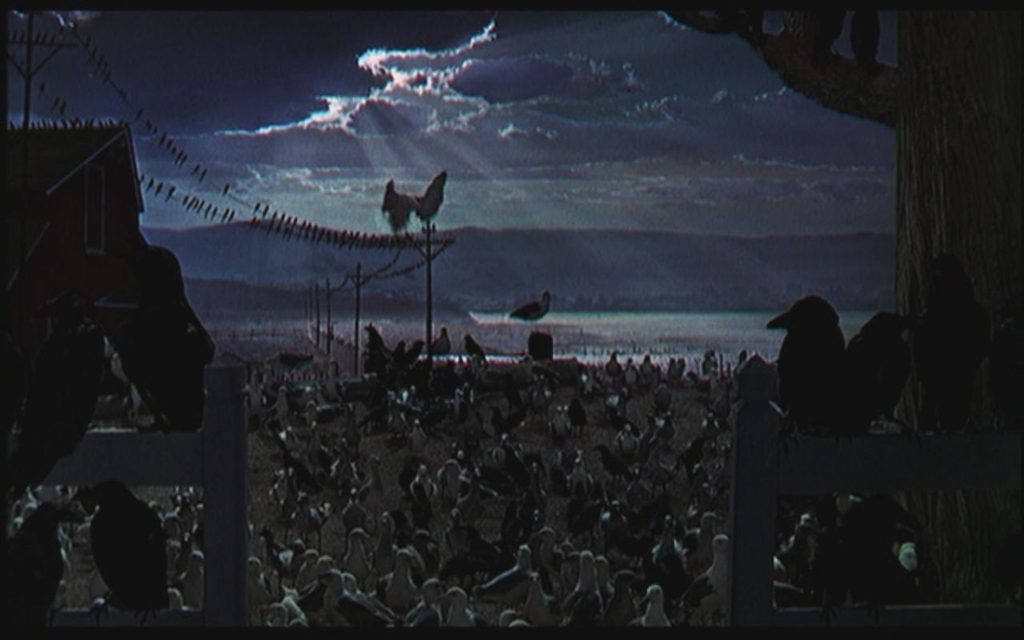

The terrifying concept of wild birds turning upon humans was presented to cinema audiences in 1963 with the release of Alfred Hitchcock’s screen adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s short story, The Birds, first published in 1952. The idea was not entirely new, however, and in today’s post I’m going to focus on two earlier novels: Melville Davisson Post’s The Revolt of the Birds (1927) and Frank Baker’s The Birds (1936.)

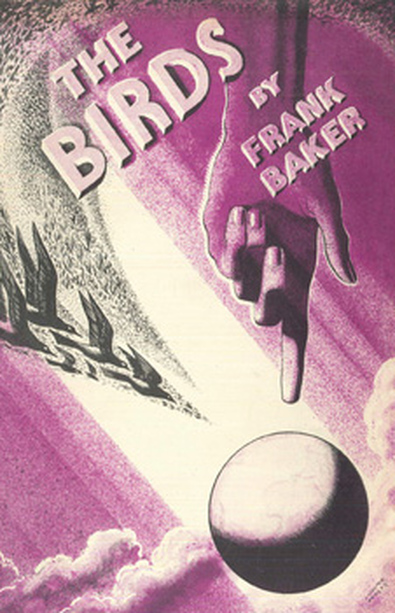

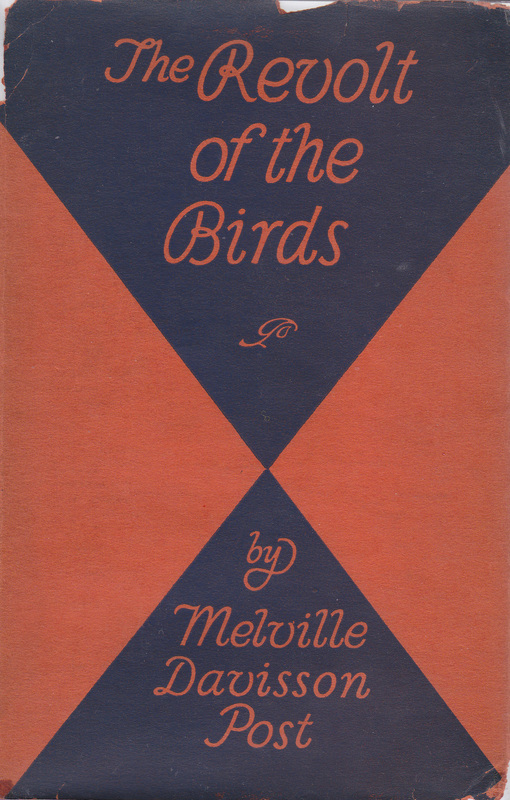

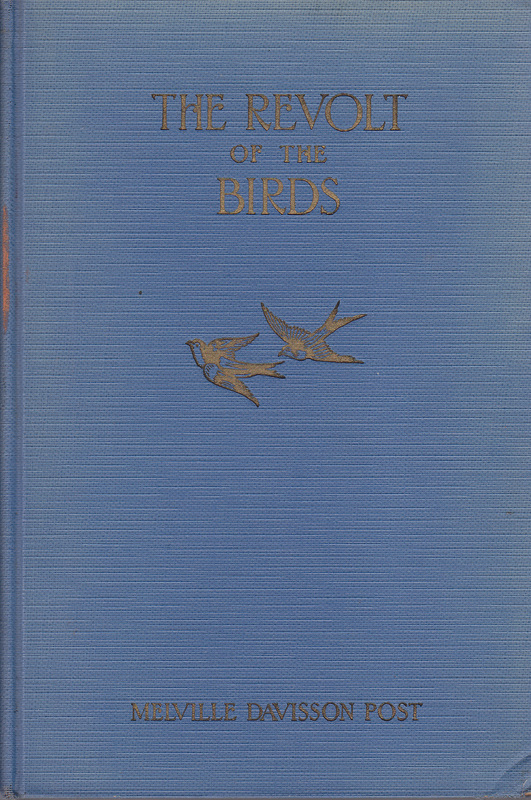

Dust jacket of the first edition

The binding, blind-stamped with gilt images of birds in flight

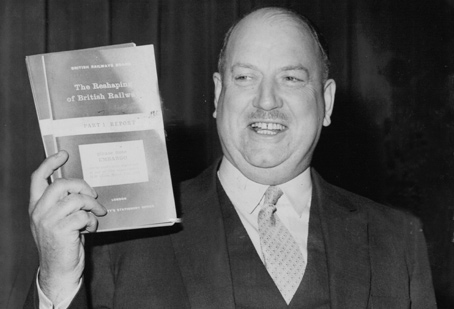

West Virginian lawyer and author Melville Davisson Post (1871-1930) is perhaps best remembered now as a crime writer, and the creator of such brilliant detectives as Uncle Abner, Randolph Mason, Colonel Braxton and Sir Henry Marquis of Scotland Yard. A qualified lawyer, he had travelled in Europe and beyond, and his prolific output reflects both his wide experiences and love of the great outdoors. The Revolt of the Birds was published in New York by Appleton in 1927, three years before Post died following a fall from his horse.

The Revolt of the Birds is set in the China Sea, and – rather like an M.R. James ghost story – is relayed through an anonymous narrator as he listens to Bennett, a seaman with the notorious Wu Fan Shipping Company. The two men are seated in a warehouse bar in Hong Kong. Bennett, an Englishman, has a copy of The Times and The Passing of Arthur which shows ‘quaint pictures of the three queens, who came in the legend, in a mystic barge to take Arthur to Avalon.’ When they start discussing whether or not such a thing could ever happen, the conversation shifts to strange happenings in the Orient and Bennett begins to tell his tale – about Arthur Hudson, his unhappy affair with an English girl, his dreams of a mysterious ‘slender, dark-haired girl’ who always appears with a flock of birds around her or beside her, and his quest to find this girl in the islands of the China Sea…. The Revolt of the Birds differs from Du Maurier’s story in one very significant point – the intention of the birds towards the humans – but it introduced the idea of a large number of birds acting together in concert against the laws of nature.

There had been some precedents for this idea – Arthur Machen’s The Terror (1917), for example, features sustained attacks on Cornish folk from an array of wild animals, including birds and moths. The disturbing suggestion that individual birds might work together in order to carry out an organised mass attack also appeared in Philip Macdonald’s short-story ‘Our Feathered Friends’ which was published in Lady Cynthia Asquith’s anthology When Churchyards Yawn (London: Hutchinson, 1931.) Macdonald actually worked as a screenwriter on Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) – also an adaptation of a Du Maurier story – and ‘Our Feathered Friends’ was reprinted in the anthology

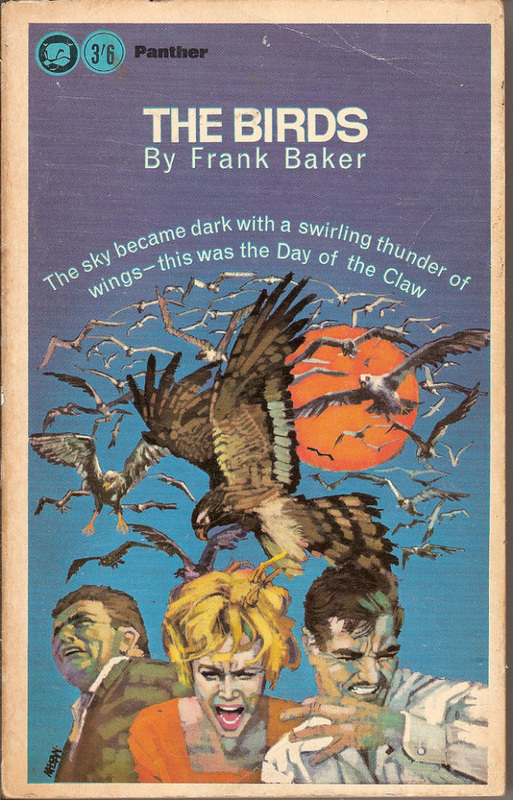

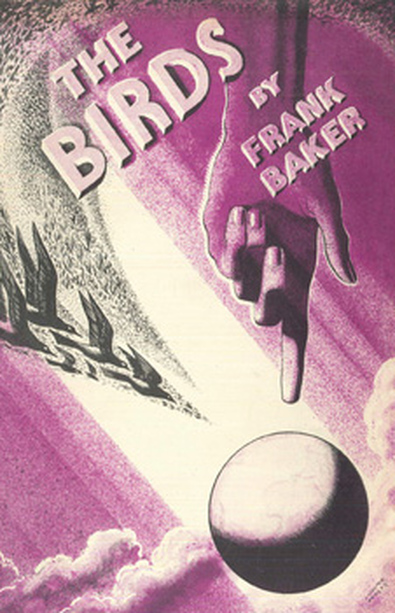

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Stories for Late at Night (New York: Random House, 1961.)Five years after Macdonald’s story, author Frank Baker (1908-82) published his full-length novel The Birds, exploring the possibility of birds carrying out a sustained war of terror against mankind.

The Birds (London: Peter Davies, 1936) dust jacket

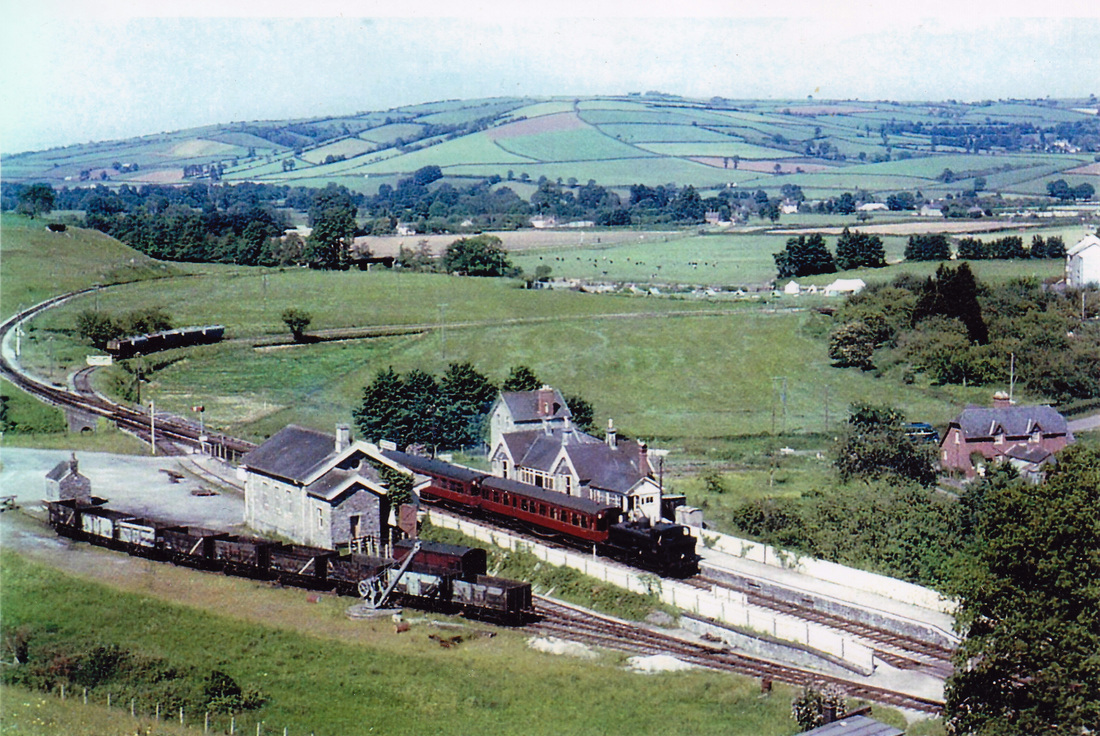

There is no reason to doubt the claim of Daphne du Maurier that she was completely unaware of the existence of Baker’s novel when she came to write her own story with the same title. Apart from the basic concept, the two texts have little in common, and she actually drew her inspiration from something she witnessed near her Cornish home at Menabilly House. near Fowey. She was able to rent Menabilly from 1943 until 1969 because of the success of the book and film Rebecca, but she had known the area since the late 1920s when the family began taking holidays there, and was friendly with many of the locals. One day, while walking across to Menabilly Barton farm from her house, she saw a farmer named Tommy Dunn out ploughing in his field above Polridmouth Beach. Above his head, seagulls were swooping and diving, and she began to wonder what might happen if they suddenly began to attack….

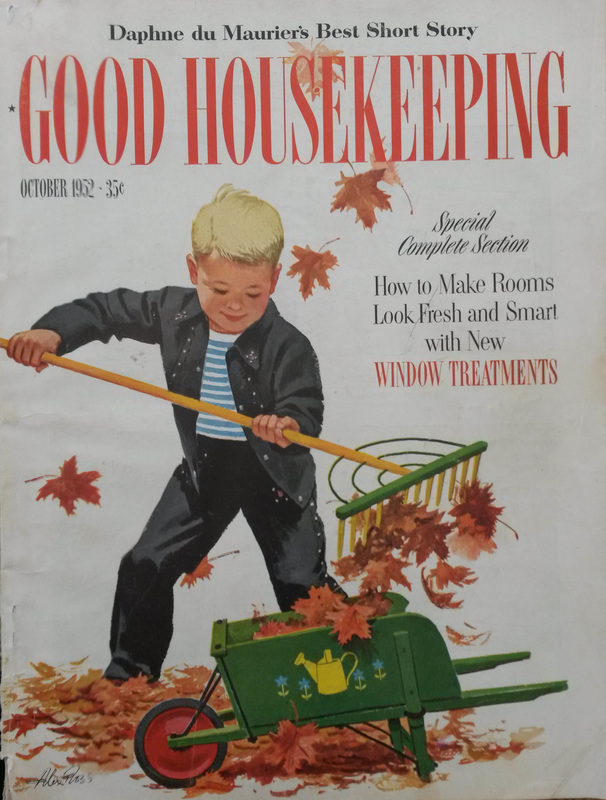

She went home and began to develop this idea, turning Tommy Dunn into Nat Hocken, and suggesting that the birds become aggressive after a harsh winter with little food. Seagulls are the first to start attacking, but they are soon joined by birds of prey and finally even small birds. The setting is clearly rural, the characters are limited to Nat’s family and neighbours, and the atmosphere is reminiscent of wartime Britain with its fears about coastal invasion and German air raids.The story was first published in Good Housekeeping magazine in October 1952, with the text broken up into fragments and printed between pages 54 and 132, interspersed with sections of other short stories and juxtaposed with dozens of housekeeping tips and adverts: “Bread stays good longer when protected with ‘Mycoban,'” “Childcraft: America’s Famous (14-volume) Child Guidance Plan” or “Jell-O Salads: Like to add a touch of glamour to dinner tonight?” This homely material seems incongruous with the grim subject matter of Du Maurier’s story, which the editors clearly regarded as potentially unpalatable – the tagline proclaimed: ‘The Editors present this, not as the most popular, but perhaps as the Most Distinguished Short Story of the Year.’

Reading the story within the context of ‘good housekeeping’ tips does, however, draw attention to the prominence of domestic and familial concerns. Nat is a former soldier who was injured during the war and receives a disability pension, but works part time on local farms doing light work in order to provide for his wife and two young children, Jill and Johnny. When the bird attacks begin, he uses his handyman skills to protect his family, boarding up windows and setting up barbed wire barriers, while his (unnamed) wife deals with the housekeeping matters: ‘It’s shopping day tomorrow, you know that. I don’t keep uncooked food about. Butcher doesn’t call till the day after.’ (Fridges were still a rarity in Britain in the early 1960s.) To distract the children from the horror, she makes them an early supper: ‘Something for a treat – toasted cheese, eh? Something we all like?’ Little details such as the need to stock up on candles, or heating up left-overs for the children, would resonate with the magazine’s readers, perhaps prompting them to think about how well they would cope in such circumstances.

1952 artwork by Seymour Mednick

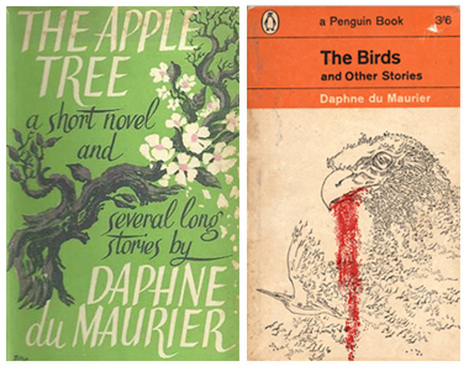

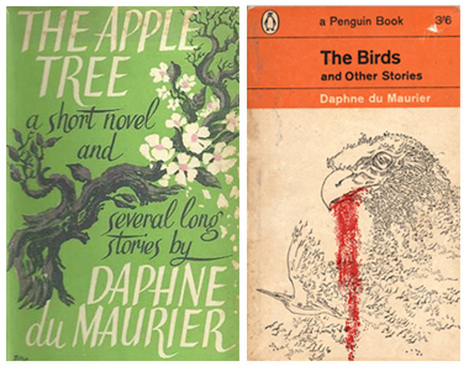

The story was reprinted in Du Maurier’s collection, The Apple Tree: a short novel and several long stories (London: Victor Gollancz, 1952.) Editions of the anthology published after the movie were issued under the title of The Birds to capitalize on the publicity.

Comparison of the 1952 and 1963 covers

Hitchcock – who had made film adaptations of Du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn (1939) and Rebecca (1940) – spotted the story and included it in his anthology Alfred Hitchcock Presents: my Favorites in Suspense (New York: Random House, 1959) as well as securing the film rights. He was reminded of the story after reading newspaper reports of bird attacks in the Californian press in April 1960 and August 1961 and within a few weeks had commissioned Evan Hunter to write a screenplay – but one that retained only the title and basic concept of Du Maurier’s story. Apart from the obvious switch from Cornwall to California, the changes are too numerous to mention; it is only really in the siege scenes in the house where Du Maurier’s story can be recognised, although here and there little echoes of phrases and events recur. Other elements – such as the attack on a woman in a telephone booth, and the intrusion of an unusual female into the relationship between the male hero and his widowed mother – can be traced back to Baker’s novel.

In 1962, when Baker heard that a film was being made of The Birds without any apparent reference to his story, he wrote to both Hitchcock and Du Maurier to protest. The director never replied, but Du Maurier responded with great sympathy; anyone who has read her letters will be aware of the tender solicitude she often showed towards her correspondents, answering questions in detail and almost acting as an ”agony aunt’ towards many of the lonely souls who contacted her.

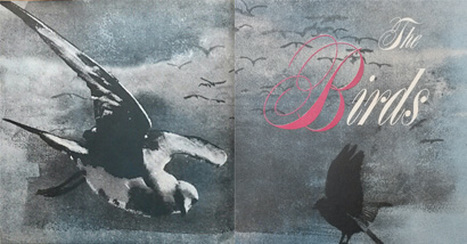

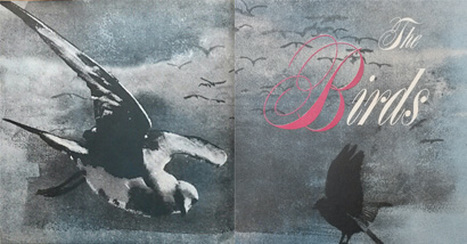

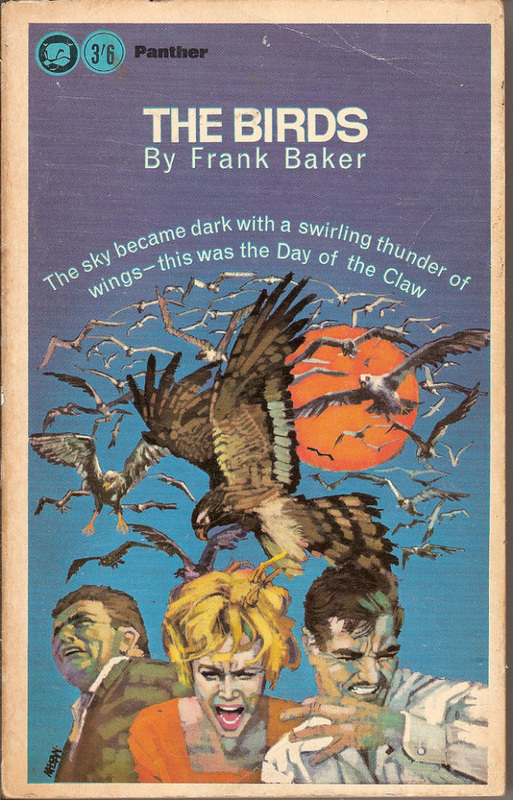

In the wake of the film, Frank Baker’s novel was reissued in 1964 as a Panther paperback

|

|

Baker heavily revised the text of his novel for the 1964 edition but only a fraction of these changes were implemented by Panther.

A new edition was published by Valancourt Press in 2013 which incorporates all of Baker’s original revisions, and comes with a nine page introduction by Ken Mogg, who runs ‘The MacGuffin’ webpage devoted to Hitchcock scholarship. Those wishing to know more about Baker’s life should read Paul Newman’s biography, The Man Who Unleashed The Birds: Frank Baker and his Circle (Abraxas Editions, 2010.)

|